14: Government

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 108298

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Chapter 14: Government

In this chapter we will explore:

| 14.1 | Market failure and the role of government |

| 14.2 | Fiscal federalism in Canada |

| 14.3 | Federal-provincial relations and powers |

| 14.4 | Redistribution to individuals |

| 14.5 | Regulatory activity and competition policy |

Governments have a profound impact on economies. The economies of Scandinavia are very different from those in North America. North and South Korea are night and day, even though they were identical several decades ago. Canada and Argentina were very similar in the early decades of the twentieth century. Both had abundant space, natural resources and migrants. Today Canada is one of the most prosperous economies in the world, while Argentina struggles as a middle-income economy.

Governments are not peripheral to the marketplace. They can facilitate or hinder the operation of markets. They can ignore poverty or implement policies to support those on low income and those who are incapacitated. Governments can treat the economy as their fiefdoms, as has been the case for decades in many underdeveloped economies. By assuming the role of warlords, local governors inhibit economic development, because the fruits of investment and labour are subject to capture by the ruling power elite.

In Canada we take for granted the existence of a generally benign government that serves the economy, rather than one which expects the economy to serve it. The separation of powers, the existence of a constitution, property rights, a police force, and a free press are all crucial ingredients in the mix that ferments economic development and a healthy society.

The analysis of government is worthy not just of a full course, but a full program of study. Accordingly, our objective in this chapter must be limited. We begin by describing the various ways in which markets may be inadequate and what government can do to remedy these deficiencies. Next we describe the size and scope of government in Canada, and define the sources of government revenues. On the expenditure side, we emphasize the redistributive and transfer roles that are played by Canadian governments. Tax revenues, particularly at the federal level, go predominantly to transfers rather than the provision of goods and services. Finally we examine how governments seek to control, limit and generally influence the marketplace: How do governments foster the operation of markets in Canada? How do they attempt to limit monopolies and cartels? How do they attempt to encourage the entry of new producers and generally promote a market structure that is conducive to competition, economic growth and consumer well-being?

14.1 Market failure

Markets are fine institutions when all of the conditions for their efficient operation are in place. In Chapter 5 we explored the meaning of efficient resource allocation, by developing the concepts of consumer and producer surpluses. But, while we have emphasized the benefits of efficient resource allocation in a market economy, there are many situations where markets deliver inefficient outcomes. Several problems beset the operation of markets. The principal sources of market failure are: Externalities, public goods, asymmetric information, and the concentration of power. In addition markets may produce outcomes that are unfavourable to certain groups – perhaps those on low incomes. The circumstances described here lead to what is termed market failure.

Market failure defines outcomes in which the allocation of resources is not efficient.

Externalities

A negative externality is one resulting, perhaps, from the polluting activity of a producer, or the emission of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. A positive externality is one where the activity of one individual confers a benefit on others. An example here is where individuals choose to get immunized against a particular illness. As more people become immune, the lower is the probability that the illness can propagate itself through hosts, and therefore the greater the benefits to those not immunized.

Solutions to these market failures come in several forms: Government taxes and subsidies, or quota systems that place limits on the production of products generating externalities. Such solutions were explored in Chapter 5. Taxes on gasoline discourage its use and therefore reduce the emission of poisons into the atmosphere. Taxes on cigarettes and alcohol lower the consumption of goods that may place an additional demand on our publicly-funded health system. The provision of free, or low-cost, immunization against specific diseases to children benefits the whole population.

These measures attempt to compensate for the absence of a market in certain activities. Producers may not wish to pay for the right to emit pollutants, and consequently if the government steps in to counter such an externality, the government is effectively implementing a solution to the missing market.

Public goods

Public goods are sometimes called collective consumption goods, on account of their non-rivalrous and non-excludability characteristics. For example, if the government meteorological office provides daily forecasts over the nation's airwaves, it is no more expensive to supply that information to one million than to one hundred individuals in the same region. Its provision to one is not rivalrous with its provision to others – in contrast to private goods that cannot be 'consumed' simultaneously by more than one individual. In addition, it may be difficult to exclude certain individuals from receiving the information.

Public goods are non-rivalrous, in that they can be consumed simultaneously by more than one individual; additionally they may have a non-excludability characteristic.

Examples of such goods and services abound: Highways (up to their congestion point), street lighting, information on trans-fats and tobacco, or public defence provision. Such goods pose a problem for private markets: If it is difficult to exclude individuals from their consumption, then potential private suppliers will likely be deterred from supplying them because the suppliers cannot generate revenue from free-riders. Governments therefore normally supply such goods and services. But how much should governments supply? An answer is provided with the help of Figure 14.1.

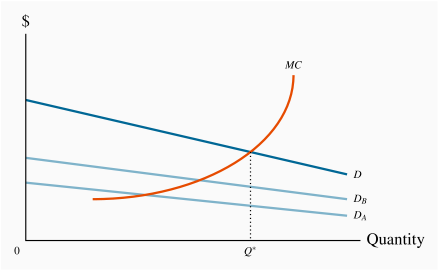

This is a supply-demand diagram with a difference. The supply side is conventional, with the MC of production representing the supply curve. An efficient use of the economy's resources, we already know, dictates that an amount should be produced so that the cost at the margin equals the benefit to consumers at the margin. In contrast to the total market demand for private goods, which is obtained by summing individual demands horizontally, the demand for public goods is obtained by summing individual demands vertically.

Figure 14.1 depicts an economy with just two individuals whose demands for street lighting are given by DA and DB. These demands reveal the value each individual places on the various output levels of the public good, measured on the x-axis. However, since each individual can consume the public good simultaneously, the aggregate value of any output produced is the sum of each individual valuation. The valuation in the market of any quantity produced is therefore the vertical sum of the individual demands. D is the vertical sum of DA and DB, and the optimal output is Q×. At this equilibrium each individual consumes the same quantity of street lighting, and the MC of the last unit supplied equals the value placed upon it by society – both individuals. Note that this 'optimal' supply depends upon the income distribution, as we have stated several times to date. A different distribution of income may give rise to different demands DA and DB, and therefore a different 'optimal' output.

Efficient supply of public goods is where the marginal cost equals the sum of individual marginal valuations, and each individual consumes the same quantity.

Wikipedia is one of the largest on-line sources of free information in the world. It is an encyclopedia that functions in multiple languages and that furnishes information on millions of topics. It is freely accessible, and is maintained and expanded by its users. Google is the most frequently used search engine on the World Wide Web. It provides information to millions of users simultaneously on every subject imaginable. But it is not quite free of charge; when the user searches she supplies information on herself that can be used profitably by Google in its advertising. MOOCs are 'monster open online courses' offered by numerous universities, frequently for no charge to the student. Are these services public goods in the sense we have described?

Very few goods and services are pure public goods, some have the major characteristics of public goods nonetheless. In this general sense, Google, Wikipedia and MOOCs have public good characteristics. Wikipedia is funded by philanthropic contributions, and its users expand its range by posting information on its servers. Google is funded from advertising revenue. MOOCs are funded by university budgets.

A pure public good is available to additional users at zero marginal cost. This condition is essentially met by these services since their server capacity rarely reaches its limit. Nonetheless, they are constantly adding server capacity, and in that sense cannot furnish their services to an unlimited number of additional users at no additional cost.

Knowledge is perhaps the ultimate public good; Wikipedia, Google and MOOCs all disseminate knowledge, knowledge which has been developed through the millennia by philosophers, scientists, artists, teachers, research laboratories and universities.

A challenge in providing the optimal amount of government-supplied public goods is to know the value that users may place upon them – how can the demand curves DA and DB, be ascertained, for example, in Figure 14.1? In contrast to markets for private goods, where consumer demands are essentially revealed through the process of purchase, the demands for public goods may have to be uncovered by means of surveys that are designed so as to elicit the true valuations that users place upon different amounts of a public good. A second challenge relates to the pricing and funding of public goods: For example, should highway lighting be funded from general tax revenue, or should drivers pay for it? These are complexities that are beyond our scope of our current inquiry.

Asymmetric information

Markets for information abound in the modern economy. Governments frequently supply information on account of its public good characteristics. But the problem of asymmetric information poses additional challenges. Asymmetric information is where at least one party in an economic relationship has less than full information. This situation characterizes many interactions: Life-insurance companies do not have perfect information on the lifestyle and health of their clients; used vehicle buyers may not know the history of the vehicles they are buying.

Asymmetric information is where at least one party in an economic relationship has less than full information and has a different amount of information from another party.

Asymmetric information can lead to two kinds of problems. The first is adverse selection. For example, can the life-insurance company be sure that it is not insuring only the lives of people who are high risk and likely to die young? If primarily high-risk people buy such insurance then the insurance company must set its premiums accordingly: The company is getting an adverse selection rather than a random selection of clients. Frequently governments decide to run universal compulsory-membership insurance plans (auto or health are examples in Canada) precisely because they may not wish to charge higher rates to higher-risk individuals.

Adverse selection occurs when incomplete or asymmetric information describes an economic relationship.

A related problem is moral hazard. If an individual does not face the full consequences of his actions, his behaviour may be influenced: if a homeowner has a fully insured home he may be less security conscious than an owner who does not.

In Chapter 7 we described how US mortgage providers lent large sums to borrowers with uncertain incomes in the early years of the new millennium. The individuals responsible for the lending were being rewarded on the basis of the amount lent, not the safety of the loan. Nor were the lenders responsible for loans that were not repaid. This 'sub-prime mortgage crisis' was certainly a case of moral hazard.

Moral hazard may characterize behaviour where the costs of certain activities are not incurred by those undertaking them.

Solutions to these problems do not always involve the government, but in critical situations do. For example, the government requires most professional societies and orders to ensure that their members are trained, accredited and capable. Whether for a medical doctor, a plumber or an engineer, a license or certificate of competence is a signal that the work and advice of these professionals is bona fide. Equally, the government sets standards so that individuals do not have to incur the cost of ascertaining the quality of their purchases – bicycle helmets must satisfy specific crash norms; so too must air-bags in automobiles.

These situations differ from those where solutions to the information problem can be dealt with reasonably well in the market place. For example, with the advent of buyer and seller rating on Airbnb, a potential renter can learn of the quality of the accommodation he is considering, and the letor can assess the potential renter.

Concentration of power

Monopolistic and imperfectly-competitive market structures can give rise to inefficient outcomes, in the sense that the value placed on the last unit of output does not equal the cost at the margin. This arises because the supplier uses his market power in order to maximize profits by limiting output and selling at a higher price.

What can governments do about such power concentrations? Every developed economy has a body similar to Canada's Competition Bureau. Such regulatory bodies are charged with seeing that the interests of the consumer, and the economy more broadly, are represented in the market place. Interventions, regulatory procedures and efforts to prevent the abuse of market power come in a variety of forms. These measures are examined in Section 14.5.

Unfavourable market outcomes

Even if governments successfully address the problems posed by the market failures described above, there is nothing to guarantee that market-driven outcomes will be 'fair', or accord with the prevailing notions of justice or equity. The marketplace generates many low-paying jobs, unemployment and poverty. The concentration of economic power has led to the growth in income and wealth inequality in many economies. Governments, to varying degrees, attempt to moderate these outcomes through a variety of social programs and transfers that are discussed in Section 14.4.

14.2 Fiscal federalism: Taxing and spending

Canada is a federal state, in which the federal, provincial and municipal governments exercise different powers and responsibilities. In contrast, most European states are unitary and power is not devolved to their regions to the same degree as in Canada or the US or Australia. Federalism confers several advantages over a unitary form of government where an economy is geographically extensive, or where identifiable differences distinguish one region from another: Regions can adopt different policies in response to the expression of different preferences by their respective voters; smaller governments may be better at experimentation and the introduction of new policies than large governments; political representatives are 'closer' to their constituents.

Despite these advantages, the existence of an additional level of government creates a tension between these levels. Such tension is evident in every federation, and federal and provincial governments argue over the appropriate division of taxation powers and revenue-raising power in general. For example, how should the royalties and taxes from oil and gas deposits offshore be distributed – to the federal government or a provincial government?

In Canada, the federal government collects more in tax revenue than it expends on its own programs. This is a feature of most federations. The provinces simultaneously face a shortfall in their own revenues relative to their program expenditure requirements. The federal government therefore redistributes, or transfers, funds to the provinces so that the latter can perform their constitutionally-assigned roles in the economy. The fact that the federal government bridges this fiscal gap gives it a degree of power over the provinces. This influence is commonly termed federal spending power.

Spending power of a federal government arises when the federal government can influence lower level governments due to its financial rather than constitutional power.

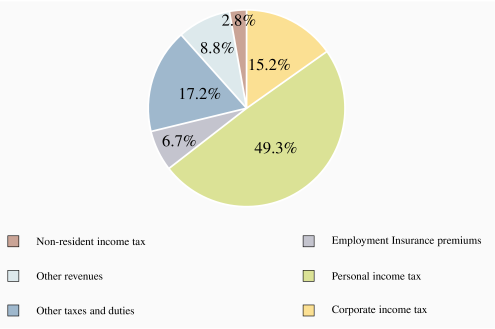

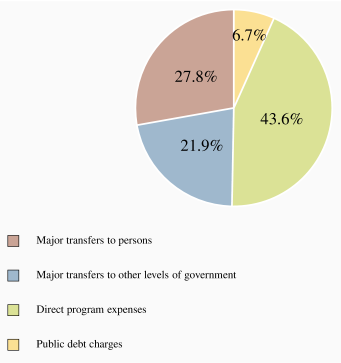

The principal revenue sources for financing federal government activity are given in Figure 14.1 for the fiscal year 2015-16, and the expenditure of these revenues is broken down in Figure 14.2. Further details are accessible in the Department of Finance's 'fiscal reference tables' at www.fin.gc.ca/frt-trf/2019/frt-trf-19-eng.asp. Total revenues for that fiscal year amounted to $333.2b, and expenditures to $346.2b.

The federal and provincial governments each transfer these revenues to individuals and other levels of government, supply goods and services directly, and also pay interest on accumulated borrowings – the national debt or provincial debt.

Provincial and local governments supply more goods and services than the federal government – health care, drug insurance, education and welfare are the responsibility of provincial and municipal governments. In contrast, national defence, the provision of main traffic arteries, Corrections Canada and a variety of transfer programs to individuals – such as Employment Insurance, Old Age Security and the Canada Pension Plan – are federally funded. The greater part of federal revenues goes towards transfers to individuals and provincial governments, as opposed to the supply of goods and services.

14.3 Federal-provincial fiscal relations

The federal government transfers revenue to the provinces using three main programs: Equalization, the Canada Social Transfer and the Canada Health Transfer. Each of these has a different objective. Equalization aims to reduce fiscal disparities among the provinces; The Canada Social Transfer (CST) is for educational and Social Assistance ('welfare') expenditures; The Canada Health Transfer (CHT) performs the same function for health.

Equalization and Territorial Funding

Canada's provinces receive unconditional funding through Canada's Equalization program, whereas the Territories receive federal funding through a separate mechanism - the Territorial Funding Formula.

"Parliament and the Government of Canada are committed to the principle of making equalization payments to ensure that provincial governments have sufficient revenues to provide reasonably comparable levels of public service at reasonably comparable levels of taxation."

This statement, from Section 36(2) of the Constitution Act of 1982, defines the purpose of Equalization. Equalization payments are unconditional – receiving provinces are free to spend the funds on public services according to their own priorities, or even use the revenue to reduce their provincial taxes. Payments are calculated according to a formula that ensures those provinces with revenue-raising ability, or fiscal capacity, below a threshold or 'standard' receive payments from the federal government to bring their capacity up to that standard.

Equalization has gone through very many changes in the several decades of its existence. Its current rules and regulations reflect the 2006 recommendations of a federal Expert Panel. The fiscal capacity of a province is measured by its ability to raise revenues from five major sources: Personal and business income taxes, sales taxes, property taxes, and natural resources. This ability is then compared to the ability of all of the provinces combined to raise revenue; if a difference or shortfall exists, the federal government transfers revenue accordingly, with the amount determined by both the population of the province and the magnitude of its per-person shortfall. Data on annual transfers for Equalization, the Territorial Funding Formula, and the CHT and CST are available at fin.gc.ca/fedprov/mtp-eng.asp

The program transferred $19.8b to the provinces in 2019-20. The recipiency status of some provinces varies from year to year. Variation in energy prices and energy-based government revenues are the principal cause of this. British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Ontario tend to receive little or zero. Manitoba, Quebec and the Atlantic Provinces have been the major recipient provinces. Quebec receives the largest single amount – approximately two thirds of the total allocation, both on account of its population size and the fact that it has a lower than average fiscal capacity. The Territories received a total of $3.9b in 2019-20 through the Territorial Funding Formula.

The Canada Social Transfer and the Canada Health Transfer

The CST is a block transfer to provinces in support of post-secondary education, Social Assistance and social services more generally. The CST came into effect in 2004. Prior to that date it was integrated with the health component of federal transfers in a program titled the Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST). The objective of the separation was to increase the transparency and accountability of federal support for health while continuing to provide funding for other objectives. The CHT is the other part of the unbundled CHST: It provides funding to the provinces for their health expenditures.

The CST and CHT funding comes in two parts: A cash transfer and tax transfer. A tax transfer essentially provides the same support as a cash transfer of equal value, but comes in a different form. In 1977 the federal government agreed with provincial governments to reduce federal personal and corporate tax rates in order to permit the provincial governments to increase the corresponding provincial rates. The net effect was that the federal government got less tax revenue and the provinces got more. And to this day, the federal and provincial governments keep a record of the implied tax transfers that arise from this long-ago agreement. This is the tax transfer component of the CST and the CHT.

The CST support is allocated to provinces and territories on an equal per-capita basis to ensure equal support for all Canadians regardless of their place of residence. The CHT is distributed likewise, and it requires the provinces to abide by the federally-legislated Canada Health Act, which demands that provincial health coverage be comprehensive, universal, portable, accessible and publicly administered.

The CHT transfer amounted to $40.4b and the CST amounted to $14.6b, in cash, for the year 2019-20. Health care and health expenditures are a core issue of policy at all levels of government on account of the envisaged growth in these expenditures that will inevitably accompany the aging of the baby-boomers.

14.4 Government-to-individual transfers

Many Canadians take pride in Canada's extensive 'social safety net' that aims to protect individuals from misfortune and the reduction of income in old age. Others believe it is too generous. While it is more supportive than the safety net in the US, the Canadian safety net is no more protective than the nets of the developed economies of the European Union. The extent of such support depends in large measure upon the degree to which governments are willing to impose, and individuals are willing to pay, higher or lower tax rates. The major elements of this umbrella of programs are the following.

The Canada and Quebec Pension Plans (C/QPP) are funded from the contributions of workers and their employers. Contributions form 9.9% of an individual's earnings up to the maximum pensionable earnings (MPE) figure of $57,400 in 2019. The contributions are shared equally by employer and employee. The Canada and Quebec components of the plan operate similarly, but are managed separately. The contribution rate to the QPP stands at 10.65%. Contributions to the plans from workers and their employers are largely transferred immediately to retired workers. Part of the contributions is invested in a fund. The objective of the plans is to ensure that some income is saved for retirement. Many individuals are not very good at planning – they constantly postpone the decision to save, so the state steps in and requires them to save. An individual contributing throughout a full-time working lifecycle can expect an annual pension of about $14,000 in 2019. The Plans provide a maximum payout of 25% of maximum insurable earnings. The objective is to provide a minimum level of retirement income, not an income that will see individuals live in great comfort.

The C/QPP plans have contributed greatly to the reduction of poverty among the elderly since their introduction in the mid-sixties. The aging of the baby-boom generation – that very large cohort born in the late forties through to the early sixties – means that the percentage of the population in the post-65 age group has begun to increase. To meet this changing demographic, the federal and provincial governments reshaped the plans in the late nineties in order to put them on a sound financial footing – primarily by increasing contributions, that in turn will enable the build-up of a CPP 'fund' that will support the aged in the following decades.

A number of recent studies in Canada on the retirement savings practices of Canadians have proposed that households on average are not saving a sufficient amount for their retirement; many households may thus see a notable decline in their incomes upon retirement. In response to this finding, the federal government agreed with the provinces in June 2016, to add a supplement to the CPP. The new federal provisions, which will be phased in over the period 2019-2025, envisage an increase in contributions that will ultimately lead to a maximum replacement rate of 33% of MPE as opposed to the current goal of 25%. However, full benefits will be experienced only by individuals contributing for their complete lifecycle, meaning that full implementation will take about four decades.

Details of the CPP and the 2016 enhancements are to be found at www.fin.gc.ca/n16/data/16-113_3-eng.asp.

Old Age Security (OAS), the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) and the Spousal Allowance (SPA) together form the second support leg for the retired. OAS is a payment made automatically to individuals once they attain the age of 65. The GIS is an additional payment made only to those on very low incomes – for example, individuals who have little income from their C/QPP or private pension plans. The SPA, which is payable to the spouse or survivor of an OAS recipient, accounts for a small part of the sums disbursed. As of 2019 the maximum annual OAS payment stood at $7,360. The federal government in 2016 reversed a plan that would have seen the eligible age for receipt of OAS move to 67.

The payments for these plans come from the general tax revenues of the federal government. Unlike the C/QPP, the benefits received are not related to the contributions that an individual makes over the working lifecycle. This program has also had a substantial impact on poverty reduction among the elderly.

Employment Insurance (EI) and Social Assistance (SA) are designed to support, respectively, the unemployed and those with no other source of income. Welfare is the common term used to describe SA. Expenditures on EI and SA are strongly cyclical. At the trough of an economic cycle the real value of expenditures on these programs greatly exceeds expenditures at the peak of the cycle. Unemployment in Canada rose above 8% in 2009, and payments to the unemployed and those on welfare reflected this dire state. The strongly cyclical pattern of the cost of these programs reflects the importance of a healthy job market: Macroeconomic conditions have a major impact on social program expenditures.

EI is funded by contributions from employees and their employers. For each dollar contributed by the employee, the employer contributes $1.4. Premiums are paid on earned income up to a maximum insurable earnings (MIE) of $53,100 in 2019. The contribution rate for employees stood at 1.62% of MIE in 2017. EI contributions and pay-outs form part of the federal government's general revenues and expenditures. There is no separate 'fund' for this program. However it is expected to operate on a break-even basis over the longer term. To reflect this, the contribution rate fluctuates with a view to maintaining a balance between payouts and revenues over a seven-year planning period.

EI is called an insurance program, but in reality it is much more than that. Certain groups systematically use the program more than others – those in seasonal jobs, those in rural areas and those in the Atlantic Provinces, for example. Accordingly, using the terminology of Chapter 7, it is not everywhere an actuarially 'fair' insurance program. Benefits payable to unemployed individuals may also depend on their family size, in addition to their work history. While most payments go in the form of 'regular' benefits to unemployed individuals, the EI program also sponsors employee retraining, family benefits that cover maternity and paternity leave, and some other specific target programs for the unemployed.

Social Assistance is provided to individuals who are in serious need of financial support – having no income and few assets. Provincial governments administer SA, although the cost of the program is partly covered by federal transfers through the Canada Social Transfer. The nineteen nineties witnessed a substantial tightening of regulations virtually across the whole of Canada. Access to SA benefits is now more difficult, and benefits have fallen in real terms since the late nineteen eighties.

Welfare dependence peaked in Canada in 1994, when 3.1 million individuals were dependent upon support. As of 2019, the total is approximately half of this, on account of more stringent access conditions, reduced benefit levels and an improved job market. Some groups in Canada believe that benefits should be higher, others believe that making welfare too generous provides young individuals with the wrong incentives in life, and may lead them to neglect schooling and skill development.

Workers Compensation supports workers injured on the job. Worker/employer contributions and general tax revenue form the sources of program revenue, and the mix varies from province-to-province. In contrast to the macro-economy-induced swings in expenditures that characterize SA and EI since the early nineties, expenditures on Worker's Compensation have remained relatively constant.

Canada Child Benefit: The major remaining pillar in Canada's social safety net is the group of payments and tax credits aimed at supporting children: The Canada Child Tax Benefit (CCTB), the Universal Child Care Benefit and the National Child Benefit Supplement were repackaged in 2016 under the title Canada Child Benefit. Child support has evolved and been enriched over the last two decades, partly with the objective of reducing poverty among households with children, and partly with a view to helping parents receiving social assistance to transition back to the labour market. As of 2016, the federal government provides an annual payment to families with children. For each child under the age of 6 the payment is $6,639 and for each child aged 6-17 the payment is $5,602. Since these payment are primarily intended for households with low and middle incomes, the amounts are progressively clawed back once the household income reaches a threshold of $30,000.

Canada's expenditure and tax policies in the nineteen seventies and eighties led to the accumulation of large government debts, as a result of running fiscal deficits. By the mid-nineties the combined federal and provincial debt reached 100% of GDP, with the federal debt accounting for the larger share. This ratio was perilously high: Interest payments absorbed a large fraction of annual government revenues, which in turn limited the ability of the government to embark on new programs or enrich existing ones. Canada's debt rating on international financial markets declined.

In 1995, Finance Minister Paul Martin addressed this problem, and over the following years program spending was pared back. Ultimately, the economy expanded and by the end of the decade the annual deficits at the federal level were eliminated.

As of 2007 the ratio of combined federal and provincial debts stood at just over 60% of GDP. However, the Great Recession of 2008 and following years saw all levels of government experience deficits, with the result that this ratio of combined debt to GDP rose again. Growth in recent years has seen that ratio fall. As of 2018-19, federal interest payments on its debt account for about 7% of its revenues (this figure stood at 28% in the early nineties). At the time of writing, interest rates are low in developed economies and so the interest costs of government debt are low. Low borrowing costs are a reason why some people favor large government spending in the form of infrastructure projects. Those who are fiscally more conservative fear rising rates in the future. The recessionary impacts of the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 will add greatly to accumulated debt, particularly at the federal level.

Debts can be measured in more than a single manner. One measure of debt is the value of all federal government bonds and financial liabilities outstanding. As of 2019-20 this value was approximately $700b. In addition to this, the federal government has outstanding liabilities to the pensions of its retired employees, and not all of these liabilities have been covered by the contributions of those employees into their pension plans. The federal government also owns assets, both financial and physical - such as office buildings. Hence these assets offset the financial liabilities. To assess the total debt picture of the Canadian economy we need to add provincial and local government debts to the federal debts, and then consider the annual interest costs of this total. It turns out that the interest costs are just above 2% of GDP.

Source: Government of Canada, Fiscal Reference Tables: www.fin.gc.ca/frt-trf/2019/frt-trf-19-eng.asp

14.5 Regulation and competition policy

Goals and objectives

The goals of competition policy are relatively uniform across developed economies: The promotion of domestic competition; the development of new ideas, new products and new enterprises; the promotion of efficiency in the resource-allocation sense; the development of manufacturing and service industries that can compete internationally.

In addition to these economic objectives, governments and citizens frown upon monopolies or monopoly practices if they lead to an undue concentration of political power. Such power can lead to a concentration of wealth and influence in the hands of an elite.

Canada's regulatory body is the Competition Bureau, whose activity is governed primarily by the Competition Act of 1986. This act replaced the Combines Investigation Act. The Competition Tribunal acts as an adjudication body, and is composed of judges and non- judicial members. This tribunal can issue orders on the maintenance of competition in the marketplace. Canada has had anti-combines legislation since 1889, and the act of 1986 is the most recent form of such legislation and policy. The Competition Act does not forbid monopolies, but it does rule as unlawful the abuse of monopoly power. Canada's competition legislation is aimed at anti-competitive practices, and a full description of its activities is to be found on its website at www.competitionbureau.gc.ca. Let us examine some of these proscribed policies.

Anti-competitive practices

Anti-competitive practices may either limit entry into a sector of the economy or force existing competitors out. In either case they lead to a reduction in competition.

Mergers may turn competitive firms into a single organization with excessive market power. The customary justification for mergers is that they permit the merged firms to achieve scale economies that would otherwise be impossible. Such scale economies may in turn result in lower prices in the domestic or international market to the benefit of the consumer, but may alternatively reduce competition and result in higher prices. Equally important in this era of global competition is the impact of a merger on a firm's ability to compete internationally.

Mergers can be of the horizontal type (e.g. two manufacturers of pre-mixed concrete merge) or vertical type (a concrete manufacturer merges with a cement manufacturer). In a market with few suppliers mergers have the potential to reduce domestic competition.

Cartels aim to restrict output and thereby increase profits. These formations are almost universally illegal in individual national economies.

While cartels are one means of increasing prices, price discrimination is another, as we saw when studying monopoly behaviour. For example, if a concrete manufacturer makes her product available to large builders at a lower price than to small-scale builders – perhaps because the large builder has more bargaining power – then the small builder is at a competitive disadvantage in the construction business. If the small firm is forced out of the construction business as a consequence, then competition in this sector is reduced.

We introduced the concept of predatory pricing in Chapter 11. Predatory pricing is a practice that is aimed at driving out competition by artificially reducing the price of one product sold by a supplier. For example, a dominant nationwide transporter could reduce price on a particular route where competition comes from a strictly local competitor. By 'subsidizing' this route from profits on other routes, the dominant firm could undercut the local firm and drive it out of the market.

Predatory pricing is a practice that is aimed at driving out competition by artificially reducing the price of one product sold by a supplier.

Suppliers may also refuse to deal. If the local supplier of pre-mixed concrete refuses to sell the product to a local construction firm, then the ability of such a downstream firm to operate and compete may be compromised. This practice is similar to that of exclusive sales and tied sales. An exclusive sale might involve a large vegetable wholesaler forcing her retail clients to buy only from this supplier. Such a practice might hurt the local grower of aubergines or zucchini, and also may prevent the retailer from obtaining some of her vegetables at a lower price or at a higher quality elsewhere. A tied sale is one where the purchaser must agree to purchase a bundle of goods from a supplier.

Refusal to deal: an illegal practice where a supplier refuses to sell to a purchaser.

Exclusive sale: where a retailer is obliged (perhaps illegally) to purchase all wholesale products from a single supplier only.

Tied sale: one where the purchaser must agree to purchase a bundle of goods from a supplier.

Resale price maintenance involves the producer requiring a retailer to sell a product at a specified price. This practice can hurt consumers since they cannot 'shop around'. In Canada, we frequently encounter a 'manufacturer's suggested retail price' for autos and durable goods. But since these prices are not required, the practice conforms to the law.

Resale price maintenance is an illegal practice wherein a producer requires sellers to maintain a specified price.

Bid rigging is an illegal practice in which normally competitive bidders conspire to fix the awarding of contracts or sales. For example, two builders, who consider bidding on construction projects, may decide that one will bid seriously for project X and the other will bid seriously on project Y. In this way they conspire to reduce competition in order to make more profit.

Bid rigging is an illegal practice in which bidders (buyers) conspire to set prices in their own interest.

Deception and dishonesty in promoting products can either short-change the consumer or give one supplier an unfair advantage over other suppliers.

Enforcement

The Competition Act is enforced through the Competition Bureau in a variety of ways. Decisions on acceptable business practices are frequently reached through study and letters of agreement between the Bureau and businesses. In some cases, where laws appear to have been violated, criminal proceedings may follow.

Regulation, deregulation and privatization

The last three decades have witnessed a significant degree of privatization and deregulation in Canada, most notably in the transportation, communication and energy sectors. Modern deregulation in the US began with the passage of the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978, and was pursued with great energy under the Reagan administration in the eighties. The Economic Council of Canada produced an influential report in 1981, titled "Reforming Regulation," on the impact of regulation and possible deregulation of specific sectors. The Economic Council proposed that regulation in some sectors was inhibiting competition, entry and innovation. As a consequence, the interests of the consumer were in danger of becoming secondary to the interests of the suppliers.

Telecommunications provision, in the era when the telephone was the main form of such communication, was traditionally viewed as a natural monopoly. The Canadian Radio and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) regulated its rates. The industry has developed dramatically in the last two decades with the introduction of satellite-facilitated communication, the internet, multi-purpose cable networks, cell phones and service integration.

Transportation, in virtually all forms, has been deregulated in Canada since the nineteen eighties. Railways were originally required to subsidize the transportation of grain under the Crow's Nest Pass rate structure. But the subsidization of particular markets requires an excessive rate elsewhere, and if the latter markets become subject to competition then a competitive system cannot function. This structure, along with many other anomalies, was changed with the passage of the Canada Transportation Act in 1996.

Trucking, historically, has been regulated by individual provinces. Entry was heavily controlled prior to the federal National Transportation Act of 1987, and subsequent legislation introduced by a number of provinces, have made for easier entry and a more competitive rate structure.

Deregulation of the airline industry in the US in the late seventies had a considerable influence on thinking and practice in Canada. The Economic Council report of 1981 recommended in favour of easier entry and greater fare competition. These policies were reflected in the 1987 National Transportation Act. Most economists are favourable to deregulation and freedom to enter, and the US experience indicated that cost reductions and increased efficiency could follow. In 1995 an agreement was reached between the US and Canada that provided full freedom for Canadian carriers to move passengers to any US city, and freedom for US carriers to do likewise, subject to a phase-in provision.

The National Energy Board regulates the development and transmission of oil and natural gas. But earlier powers of the Board, involving the regulation of product prices, were eliminated in 1986, and controls on oil exports were also eliminated.

Agriculture remains a highly controlled area of the economy. Supply 'management', which is really supply restriction, and therefore 'price maintenance', characterizes grain, dairy, poultry and other products. Management is primarily through provincial marketing boards.

The role of the sharing economy

The arrival of universal access to the internet has seen the emergence of what is known as the Sharing economy throughout the world. This expression is used to describe commercial activities that, in the first place, are internet-based. Second, suppliers in the sharing economy use resources in the market place that were initially aimed at a different purpose. Airbnb and Uber are good examples of companies in sectors of the economy where sharing is possible. In Uber's case, the 'ride-share' drivers initially purchased their vehicles for private use, and subsequently redirected them to commercial use. Airbnb is a communication corporation that enables the owners of spare home capacity to sell the use of that capacity to short-term renters. With the maturation of such corporations, the concept of 'initial' and 'secondary' use becomes blurred.

Sharing economy: involves enterprises that are internet based, and that use production resources that have use outside of the marketplace.

The importance of the sharing economy is that it provides an additional source of competition to established suppliers, and therefore limits the market power of the latter. At the same time, the emergence of the sharing economy poses a new set of regulatory challenges: If traditional taxis are required to purchase operating permits (medallions), and the ride-share drivers do not require such permits, is there a reasonable degree of competition in the market, and if not what is the appropriate solution? Should the medallion requirement be abolished, or should ride-share drivers be required to purchase one? In the case of Airbnb, the suppliers operate outside of the traditional 'hotel' market. In general they do not charge sales taxes or face any union labour agreements. What is the appropriate response from governments? And how should the sharing economy be taxed?

Price regulation

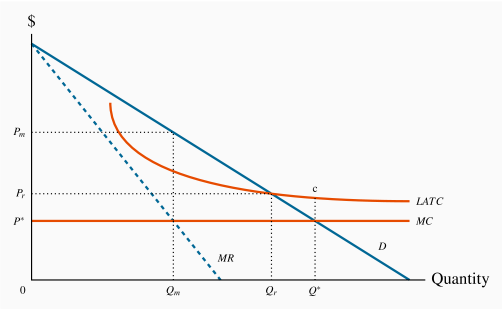

Regulating monopolistic sectors of the economy is one means of reducing their market power. In Chapter 11 it was proposed that indefinitely decreasing production costs in an industry means that the industry might be considered as a 'natural' monopoly: Higher output can be produced at lower cost with fewer firms. Hence, a single supplier has the potential to supply the market at a lower unit cost; unless, that is, such a single supplier uses his monopoly power. To illustrate how the consumer side may benefit from this production structure through regulation, consider Figure 14.2. For simplicity suppose that long-run marginal costs are constant and that average costs are downward sloping due to an initial fixed cost. The profit-maximizing (monopoly) output is where MR=MC at Qm and is sold at the price Pm. This output is inefficient because the willingness of buyers to pay for additional units of output exceeds the additional cost. On this criterion the efficient output is Q×. But LATC exceeds price at Q×, and therefore it is not feasible for a producer.

One solution is for the regulating body to set a price-quantity combination of Pr, and Qr, where price equals average cost and therefore generates a normal rate of profit. This output level is still lower than the efficient output level Q×, but is more efficient than the profit-maximizing output Qm. It is more efficient in the sense that it is closer to the efficient output Q×. A problem with such a strategy is that it may induce lax management: If producers are allowed to charge an average-cost price, then there is a reduced incentive for them to keep strict control of their costs in the absence of competition in the marketplace.

A second solution to the declining average cost phenomenon is to implement

what is called a two-part tariff. This means that customers

pay an 'entry fee' in order to be able to purchase the good. For example, in many jurisdictions hydro or natural gas subscribers may pay a fixed charge per month for their

supply line and supply guarantee, and then pay an additional charge that

varies with quantity. In this way it is possible for the supplier to charge

a price per unit of output that is closer to marginal cost and still make a

profit, than under an average cost pricing formula. In terms of Figure 14.2,

the total value of entry fees, or fixed components of

the pricing, would have to cover the difference between MC and LATC

times the output supplied. In Figure 14.2 this implies

that if the efficient output ![]() is purchased at a price equal to

the MC the producer loses the amount (c–MC) on each unit sold. The

access fees would therefore have to cover at least this value.

is purchased at a price equal to

the MC the producer loses the amount (c–MC) on each unit sold. The

access fees would therefore have to cover at least this value.

Such a solution is appropriate when fixed costs are high and marginal costs are low. This situation is particularly relevant in the modern market for telecommunications: The cost to suppliers of marginal access to their networks, whether it be for internet, phone or TV, is negligible compared to the cost of maintaining the network and installing capacity.

Two-part tariff: involves an access fee and a per unit of quantity fee.

Finally, a word of caution: Nobel Laureate George Stigler has argued that there is a danger of regulators becoming too close to the regulated, and that the relationship can evolve to a point where the regulator may protect the regulated firms. In contrast, Professor Philippon of New York University argues that regulators are not regulating sufficiently in the US: they have permitted an excessive number of mergers that have, in turn, reduced competition.

Key Terms

Market failure defines outcomes in which the allocation of resources is not efficient.

Public goods are non-rivalrous, in that they can be consumed simultaneously by more than one individual; additionally they may have a non-excludability characteristic.

Efficient supply of public goods is where the marginal cost equals the sum of individual marginal valuations, and each individual consumes the same quantity.

Asymmetric information is where at least one party in an economic relationship has less than full information and has a different amount of information from another party.

Adverse selection occurs when incomplete or asymmetric information describes an economic relationship.

Moral hazard may characterize behaviour where the costs of certain activities are not incurred by those undertaking them.

Spending power of a federal government arises when the federal government can influence lower level governments due to its financial rather than constitutional power.

Predatory pricing is a practice that is aimed at driving out competition by artificially reducing the price of one product sold by a supplier.

Refusal to deal: an illegal practice where a supplier refuses to sell to a purchaser.

Exclusive sale: where a retailer is obliged (perhaps illegally) to purchase all wholesale products from a single supplier only.

Tied sale: one where the purchaser must agree to purchase a bundle of goods from the one supplier.

Resale price maintenance is an illegal practice wherein a producer requires sellers to maintain a specified price.

Bid rigging is an illegal practice in which bidders (buyers) conspire to set prices in their own interest.

Sharing economy: involves enterprises that are internet based, and that use production resources that have use outside of the marketplace.

Two-part tariff: involves an access fee and a per unit of quantity fee.

Exercises for Chapter 14

An economy is composed of two individuals, whose demands for a public good – street lighting – are given by P=12–(1/2)Q and P=8–(1/3)Q.

Graph these demands on a diagram, for values of

.

.Graph the total demand for this public good by summing the demands vertically, specifying the numerical value of each intercept.

Let the marginal cost of providing the good be $5 per unit. Illustrate graphically the efficient supply of the public good (

) in this economy.

) in this economy.Illustrate graphically the area that represents the total value to the consumers of the amount

.

.

In Exercise 14.1, suppose a new citizen joins the economy, and her demand for the public good is given by P=10–(5/12)Q.

Add this individual's demand curve to the graphic for the above question and graph the new total demand curve, specifying the intercept values.

Illustrate the area on your graph that represents the new total value to the three citizens of the optimal amount supplied.

Illustrate graphically the net value to society of the new

– the total value minus the total cost.

– the total value minus the total cost.

An industry that is characterized by a decreasing cost structure has a demand curve given by P=100–Q and the marginal revenue curve by MR=100–2Q. The marginal cost is MC=4, and average cost is AC=4+188/Q.

Graph this cost and demand structure. [Hint: This graph is similar to Figure 14.2.]

Illustrate the efficient output and the monopoly output for the industry.

Illustrate on the graph the price the monopolist would charge if he were unregulated.

Optional: In Question 14.3, suppose the government decides to regulate the behaviour of the supplier, in the interests of the consumer.

Illustrate graphically the price and output that would emerge if the supplier were regulated so that his allowable price equalled average cost.

Is this greater or less than the efficient output?

Compute the AC and P that would be charged with this regulation.

Illustrate graphically the deadweight loss associated with the regulated price and compare it with the deadweight loss under monopoly.

Optional: As an alternative to regulating the supplier such that price covers average total cost, suppose that a two part tariff were used to generate revenue. This scheme involves charging the MC for each unit that is purchased and in addition charging each buyer in the market a fixed cost that is independent of the amount he purchases. If an efficient output is supplied in the market, illustrate graphically the total revenue to be obtained from the component covering a price per unit of the good supplied, and the component covering fixed cost.