Markets are fine institutions when all of the conditions for their efficient operation are in place. In Chapter 5 we explored the meaning of efficient resource allocation, by developing the concepts of consumer and producer surpluses. But, while we have emphasized the benefits of efficient resource allocation in a market economy, there are many situations where markets deliver inefficient outcomes. Several problems beset the operation of markets. The principal sources of market failure are: Externalities, public goods, asymmetric information, and the concentration of power. In addition markets may produce outcomes that are unfavourable to certain groups – perhaps those on low incomes. The circumstances described here lead to what is termed market failure.

Market failure defines outcomes in which the allocation of resources is not efficient.

Externalities

A negative externality is one resulting, perhaps, from the polluting activity of a producer, or the emission of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. A positive externality is one where the activity of one individual confers a benefit on others. An example here is where individuals choose to get immunized against a particular illness. As more people become immune, the lower is the probability that the illness can propagate itself through hosts, and therefore the greater the benefits to those not immunized.

Solutions to these market failures come in several forms: Government taxes and subsidies, or quota systems that place limits on the production of products generating externalities. Such solutions were explored in Chapter 5. Taxes on gasoline discourage its use and therefore reduce the emission of poisons into the atmosphere. Taxes on cigarettes and alcohol lower the consumption of goods that may place an additional demand on our publicly-funded health system. The provision of free, or low-cost, immunization against specific diseases to children benefits the whole population.

These measures attempt to compensate for the absence of a market in certain activities. Producers may not wish to pay for the right to emit pollutants, and consequently if the government steps in to counter such an externality, the government is effectively implementing a solution to the missing market.

Public goods

Public goods are sometimes called collective consumption goods, on account of their non-rivalrous and non-excludability characteristics. For example, if the government meteorological office provides daily forecasts over the nation's airwaves, it is no more expensive to supply that information to one million than to one hundred individuals in the same region. Its provision to one is not rivalrous with its provision to others – in contrast to private goods that cannot be 'consumed' simultaneously by more than one individual. In addition, it may be difficult to exclude certain individuals from receiving the information.

Public goods are non-rivalrous, in that they can be consumed simultaneously by more than one individual; additionally they may have a non-excludability characteristic.

Examples of such goods and services abound: Highways (up to their congestion point), street lighting, information on trans-fats and tobacco, or public defence provision. Such goods pose a problem for private markets: If it is difficult to exclude individuals from their consumption, then potential private suppliers will likely be deterred from supplying them because the suppliers cannot generate revenue from free-riders. Governments therefore normally supply such goods and services. But how much should governments supply? An answer is provided with the help of Figure 14.1.

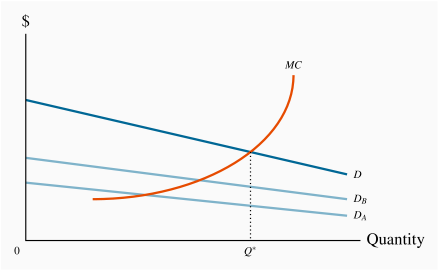

This is a supply-demand diagram with a difference. The supply side is conventional, with the MC of production representing the supply curve. An efficient use of the economy's resources, we already know, dictates that an amount should be produced so that the cost at the margin equals the benefit to consumers at the margin. In contrast to the total market demand for private goods, which is obtained by summing individual demands horizontally, the demand for public goods is obtained by summing individual demands vertically.

Figure 14.1 depicts an economy with just two individuals whose demands for street lighting are given by DA and DB. These demands reveal the value each individual places on the various output levels of the public good, measured on the x-axis. However, since each individual can consume the public good simultaneously, the aggregate value of any output produced is the sum of each individual valuation. The valuation in the market of any quantity produced is therefore the vertical sum of the individual demands. D is the vertical sum of DA and DB, and the optimal output is Q×. At this equilibrium each individual consumes the same quantity of street lighting, and the MC of the last unit supplied equals the value placed upon it by society – both individuals. Note that this 'optimal' supply depends upon the income distribution, as we have stated several times to date. A different distribution of income may give rise to different demands DA and DB, and therefore a different 'optimal' output.

Efficient supply of public goods is where the marginal cost equals the sum of individual marginal valuations, and each individual consumes the same quantity.

Application Box 14.1 Are Wikipedia, Google and MOOCs public goods?

Wikipedia is one of the largest on-line sources of free information in the world. It is an encyclopedia that functions in multiple languages and that furnishes information on millions of topics. It is freely accessible, and is maintained and expanded by its users. Google is the most frequently used search engine on the World Wide Web. It provides information to millions of users simultaneously on every subject imaginable. But it is not quite free of charge; when the user searches she supplies information on herself that can be used profitably by Google in its advertising. MOOCs are 'monster open online courses' offered by numerous universities, frequently for no charge to the student. Are these services public goods in the sense we have described?

Very few goods and services are pure public goods, some have the major characteristics of public goods nonetheless. In this general sense, Google, Wikipedia and MOOCs have public good characteristics. Wikipedia is funded by philanthropic contributions, and its users expand its range by posting information on its servers. Google is funded from advertising revenue. MOOCs are funded by university budgets.

A pure public good is available to additional users at zero marginal cost. This condition is essentially met by these services since their server capacity rarely reaches its limit. Nonetheless, they are constantly adding server capacity, and in that sense cannot furnish their services to an unlimited number of additional users at no additional cost.

Knowledge is perhaps the ultimate public good; Wikipedia, Google and MOOCs all disseminate knowledge, knowledge which has been developed through the millennia by philosophers, scientists, artists, teachers, research laboratories and universities.

A challenge in providing the optimal amount of government-supplied public goods is to know the value that users may place upon them – how can the demand curves DA and DB, be ascertained, for example, in Figure 14.1? In contrast to markets for private goods, where consumer demands are essentially revealed through the process of purchase, the demands for public goods may have to be uncovered by means of surveys that are designed so as to elicit the true valuations that users place upon different amounts of a public good. A second challenge relates to the pricing and funding of public goods: For example, should highway lighting be funded from general tax revenue, or should drivers pay for it? These are complexities that are beyond our scope of our current inquiry.

Asymmetric information

Markets for information abound in the modern economy. Governments frequently supply information on account of its public good characteristics. But the problem of asymmetric information poses additional challenges. Asymmetric information is where at least one party in an economic relationship has less than full information. This situation characterizes many interactions: Life-insurance companies do not have perfect information on the lifestyle and health of their clients; used vehicle buyers may not know the history of the vehicles they are buying.

Asymmetric information is where at least one party in an economic relationship has less than full information and has a different amount of information from another party.

Asymmetric information can lead to two kinds of problems. The first is adverse selection. For example, can the life-insurance company be sure that it is not insuring only the lives of people who are high risk and likely to die young? If primarily high-risk people buy such insurance then the insurance company must set its premiums accordingly: The company is getting an adverse selection rather than a random selection of clients. Frequently governments decide to run universal compulsory-membership insurance plans (auto or health are examples in Canada) precisely because they may not wish to charge higher rates to higher-risk individuals.

Adverse selection occurs when incomplete or asymmetric information describes an economic relationship.

A related problem is moral hazard. If an individual does not face the full consequences of his actions, his behaviour may be influenced: if a homeowner has a fully insured home he may be less security conscious than an owner who does not.

In Chapter 7 we described how US mortgage providers lent large sums to borrowers with uncertain incomes in the early years of the new millennium. The individuals responsible for the lending were being rewarded on the basis of the amount lent, not the safety of the loan. Nor were the lenders responsible for loans that were not repaid. This 'sub-prime mortgage crisis' was certainly a case of moral hazard.

Moral hazard may characterize behaviour where the costs of certain activities are not incurred by those undertaking them.

Solutions to these problems do not always involve the government, but in critical situations do. For example, the government requires most professional societies and orders to ensure that their members are trained, accredited and capable. Whether for a medical doctor, a plumber or an engineer, a license or certificate of competence is a signal that the work and advice of these professionals is bona fide. Equally, the government sets standards so that individuals do not have to incur the cost of ascertaining the quality of their purchases – bicycle helmets must satisfy specific crash norms; so too must air-bags in automobiles.

These situations differ from those where solutions to the information problem can be dealt with reasonably well in the market place. For example, with the advent of buyer and seller rating on Airbnb, a potential renter can learn of the quality of the accommodation he is considering, and the letor can assess the potential renter.

Concentration of power

Monopolistic and imperfectly-competitive market structures can give rise to inefficient outcomes, in the sense that the value placed on the last unit of output does not equal the cost at the margin. This arises because the supplier uses his market power in order to maximize profits by limiting output and selling at a higher price.

What can governments do about such power concentrations? Every developed economy has a body similar to Canada's Competition Bureau. Such regulatory bodies are charged with seeing that the interests of the consumer, and the economy more broadly, are represented in the market place. Interventions, regulatory procedures and efforts to prevent the abuse of market power come in a variety of forms. These measures are examined in Section 14.5.

Unfavourable market outcomes

Even if governments successfully address the problems posed by the market failures described above, there is nothing to guarantee that market-driven outcomes will be 'fair', or accord with the prevailing notions of justice or equity. The marketplace generates many low-paying jobs, unemployment and poverty. The concentration of economic power has led to the growth in income and wealth inequality in many economies. Governments, to varying degrees, attempt to moderate these outcomes through a variety of social programs and transfers that are discussed in Section 14.4.