26.6: Why We Use Techno Expression for Learning

- Page ID

- 89408

“We must continually remind students in the classroom that expression of different opinions and dissenting ideas affirms the intellectual process. We should forcefully explain that our role is not to teach them to think as we do but rather to teach them, by example, the importance of taking a stance that is rooted in rigorous engagement with the full range of ideas about a topic”. – Hooks (1994)

Considering Techno Expression During Course Design

Chapters 10, 11, and 13 cover course design in great detail. In this chapter we focus on those aspects of course design that relate to interaction and expression. We will give some examples and strategies for providing students with opportunities for expression in any scenario, face-to-face courses with online supplements, hybrid courses, and fully online courses. We will also discuss our own experiences with, and preferences among, these three scenarios.

When you design your own online course environment, keep interaction in the front of your mind. Many people new to using the online environment start the course design process by planning what materials they want to upload. For example, many instructors state “I just want to upload my syllabus for now.” This is a logical place to start. After all, you want the students to know up front what your expectations are, whether they are the course learning objectives, your course policies, or your grading plan. It does not take much more, though, to give students an opportunity to state their own expectations for the course. Create a threaded discussion or wiki assignment, asking students to review the syllabus and then to write one or two things that they would like to get out of the course, how the material could be made more meaningful to them or for their goals, and even their preliminary opinions about some of the main course themes or topics.

Even if you are not completely familiar with the online environment, you can go beyond just uploading a syllabus by including course materials, such as readings, presentations and lecture notes. Again, it will not require a huge effort to create one general threaded discussion to let students tell you about the applicability of the materials to their lives or studies or to express their opinions about different aspects of the content itself. If you want to make a discussion forum to gauge the effectiveness of the course materials, then Chapter 24, Evaluating and Improving Your Online Teaching Effectiveness, has many more ideas about getting student feedback and soliciting constructive recommendations.

In addition to giving students an opportunity online to discuss the course overall and its different components, we recommend giving students an opportunity to talk about themselves. Many face-to-face instructors devote some portion of the first class meeting to an icebreaker activity or student introductions. You can do the same thing online. Create a discussion forum, blog, or wiki assignment for students to state how the class will help them meet academic or professional goals, or what they expect to achieve personally. An online activity like this allows you to return to it throughout the term, assigning student reflections about their own progress towards the previously expressed goals. The assignment can also enable other student techno expressions, such as photos, brief descriptions of where they are from, or even a sense of “in the moment” place (e.g., “From my computer, I can see the pine tree in my yard through the San Francisco fog each morning”). These activities can be limited to individual student-to-teacher communication, or they can be public, so other students can provide encouragement, feedback, related stories or resources, and more.

In a field study investigating the experiences of adults engaged in a year-long, computer-mediated MA program in psychology, participants took online courses, explored aspects of their psychological and spiritual development and shared their life stories through creative writing and imagery online. The primary means of communication was within an asynchronous online conference (Caucus). Through an ethnographic participant-observation approach, supported by online transcripts, field notes, a focus group discussion, questionnaires, and phone interviews, some key themes about techno expression emerged. First, personal storytelling and virtual group discourse revealed that the participant’s sense of self-identity extended beyond the individual or personal to encompass wider aspects of relatedness to others or to the natural world. Participants reported the importance of pace and flow in online discourse as well as a sense of immersive presence. Sustained online discourse was found to be the most crucial component in creating a supportive structure for collaborative learning.

Seven key elements were cited by students as being transformative:

- combining several face-to-face meetings with virtual presence;

- community size, structure, tone, and intention;

- being a part of a self-creating, self-maintaining, and self-defining class, through flexible curriculum design and whole-group learning;

- encouragement by instructors of in-the-moment self awareness, mindfulness, and immersive presence;

- guided risk-taking through shared feelings and life experiences;

- humour, improvisation, and creative expression; and

- a shared search for meaning: Seeing all of life and education as a transformational journey (Cox, 1999).

If you have a choice, we recommend designing a hybrid course over a fully online course. Even if it means having only two face-to-face sessions—one to launch the course by setting course norms and expectations and by reading a script of online discourse to set tone, and one to close the class—this will improve students’ abilities to express themselves freely to peers.

Similarly, it is important to mix it up, with respect to the work that you assign. Apply the good lessons that we have learned from those who have explored online community building (see more about building communities in Chapter 30, Supporting E-learning through Communities of Practice), such as those that tell us to assign community roles, assign rotating facilitation, and incorporate assignments that ask students to engage in experiences offline and then to report back to the instructor or the class.

Construct Assignments that Encourage Expression

You may already have dozens of ideas, or you may have some difficulty thinking of assignments that require students to express their points of view. Below are some questions that you can use to get started during the course design process.

To whom will students express themselves?

There are a number of potential audiences to whom students could express themselves: to the instructor, to an expert in the field, to a small group of peers, to the entire class, to prospective employers, and to the public. No matter what size the audience or who is in it, students should be prepared to make their case, to state their opinions, and to answer follow-up questions. This means that over the course of a term, you should mix up the audiences for various assignments to give students practice in expressing themselves differently. For instance, a marketing student creating a video advertisement presentation will most likely behave differently for a group of peers than for an advertising professional. A special education credential student writing a reflective weblog entry about a classroom observation only for the supervising faculty member might use different language than for the public at large. These types of experiences will prepare the students not only for future coursework but also for job interviews.

How will students express themselves?

The question of how students can express themselves was discussed earlier. During the course design process, your task is to identify the best method for students to achieve the learning objectives. If you want to assign reflection activities, consider using ePortfolio, a blog, or a podcast. These reflections can ask students to describe why they did something a certain way, or they can ask for opinions about a topic. If you want to have students work in groups to perform research, use a wiki and ask students to state their viewpoints in addition to the facts related to the research topic. If you want students to give a presentation, either live or online, then use podcasts or VODcasts, have students post PowerPoint slides with audio, or have them give the presentation using an online meeting space.

Why will students want to express themselves?

Many students will want to express themselves, but not everyone is built the same way. Some students may feel uncomfortable and others may not have much experience making their own thoughts public. Therefore, it will help if you choose meaningful assignments, define the expectations, and provide examples of good work.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Techno expression rationale

“Why are we keeping a blog?

Blogging gives us a unique opportunity to think about both the way in which electronic rhetoric transforms written discourse as well as e-rhetoric’s innovative relationship to both private and public communication. In addition, keeping a blog allows you to use writing to explore issues related to digital culture, to sharpen your analytical skills, and to participate in a larger community conversation about the impact of technology on our lives” (Alfano, 2005, para. 3).

Provide Guidelines for Students

There are a number of ways that you can help students—before, during, and after the assignment. Before, the assignment, write clear instructions, including information about your policies on academic integrity and plagiarism. Provide examples of prior students’ work.

If this is the first group to do this type of assignment, go through the assignment yourself to create a model of what you consider to be good work. Let students know what could happen to their work if someone else were able to change it.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Techno expression guidelines for wikis

“REMEMBER: The work you submit is recorded and logged. Do not get mad if someone else edits your content for you, that’s the entire point of this exercise. Topics should not be ‘sat upon’ with tags such as ‘DO NOT EDIT THIS PAGE’. All topics are open to constructive addition by any member of this space. Also, keep in mind that you can always edit a page back to its previous state by clicking on the history link, clicking on the old page, and hitting the ‘revert’ link at the top” (Jones and Benick, 2006, para. 17).

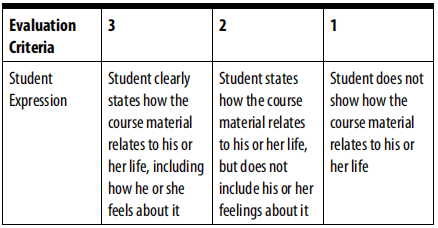

Post rubrics or grading criteria ahead of time so students know what is important and how they will be evaluated. Include one or more criteria related to originality or expression (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

During the assignment, watch for “flaming,” that is, angry or inflammatory messages (http://www.computer user.com/resources/dictionary/definition.html?lookup= 6608) in forums and chats. Keep an eye on how students are expressing themselves, and provide guidance if it seems appropriate to do so. Be sure to point out positive examples. In wikis, watch for students deleting other students’ work without permission. While it is okay for students to edit each other’s work, there are protocols for deleting. One student nominates a section for deletion and another person in the group—preferably the author—actually deletes it once there is a rough consensus.

After the assignment, use evaluation criteria such as the one shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) Include comments about how you think the students can improve.

Acknowledge Student Views

It is not enough to just create an assignment that gives students a chance to give their opinions. For this to be a part of the learning process, we need to acknowledge the students’ points of view and provide feedback. If workload is a factor, then try acknowledging just one or two ideas in the face-to-face setting. You can choose these at random, or you can pick the ideas that have generated the most discussion. The point is to let the students know that you are aware of their work and that you value their opinions.