30.6: CoPs in Practice

- Page ID

- 90423

If you are considering implementing a virtual CoP, the theoretical background and case studies presented so far should give you some knowledge of what it could accomplish and how it might function. However, getting from start to full operation involves skillful design and ongoing management to ensure success. In this section we outline guidelines and tips to help you begin and facilitate a CoP in your learning context.

Getting Started

A community of practice can form around a common problem or topic, but generally someone has to set up a structure for the community to succeed. Kim (2000) breaks the process of building community into nine strategies revolving around:

- purpose: clearly define the community you are building, why you are building it (i.e., what needs it will meet for its owners and for its members), and who its members will be;

- places: where you will bring people together. For online communities, places can include mailing lists, discussion topics, chat rooms, multiplayer games, virtual worlds, a website, or some combination of these spaces;

- profiles: ways to introduce members to each other, develop and maintain their identities, and build trust and relationships;

- roles: member roles such as newcomer, old-timer, and leader, each of which may have unique interaction and contribution needs within the community;

- leadership: those who take on roles to animate and organize the community. Kim’s examples of their tasks include greeting newcomers, coordinating events, managing programs, maintaining the infrastructure, and keeping activities lively and civil;

- etiquette: behavioural standards or social boundaries that are explicitly stated and agreed on by the community;

- events: planned and facilitated events that bring people together and help to define the community and move it forward;

- rituals: welcomes to new members, celebrations and other observances to help members feel at home and create an online culture;

- subgroups: member-run small groups with common interests, to help create a sense of intimacy and common purpose.

More simply, CoP participation becomes a function of roles and rules. Everyone has something to contribute, whether coordinators, novices, local experts, experts from outside the organization, or something in between. However, there must be some structure related to how the contributions are made. In the online education sphere, we also have to remember the expert-novice paradigm, where “experts” forget what it is like to learn particular information or skills. Often fellow novices have better explanations or advice regarding how to solve a problem, because they themselves just figured out how it works. Including people from outside the organization can inject new ideas into the group and can also help prevent “groupthink.”

Software Support

Face-to-face communities can hold physical meetings and events, but how is a virtual community supposed to interact? Technology plays a pivotal role in enabling online communities of practice to grow, to share knowledge and ideas, and to allow members to support each other as people. Choosing which technology to use for these purposes is not an easy task. If you start with a list of your desired activities and resources, you can often find help from technical support staff and Internet sites that review online tools.

Case Study: Technology Decisions for ScoPE

The process of choosing a suitable platform for the SCoPE community facilitated by Simon Fraser University was unexpectedly complex. Although organizers had decided that their most important criteria were ease of use, flexibility, ability to customize, and good communication tools, their preliminary research did not yield any existing community platforms that met their needs.

The technical support staff at SFU’s Learning & Instructional Development Centre (LIDC) considered several different solutions, starting with building an inhouse solution, then moving to the open source community platforms Sakai and TikiWiki, and finally settling on Moodle (www.moodle.org). Moodle stood out as satisfying most of our user requirements. Moodle took (literally) eight minutes to install, and following initial installation has required very little maintenance by the LIDC technical support staff. Although Moodle was developed as a course management system, branding and customizing its interface and language was straightforward, and making the changes that made SCoPE feel like an online community rather than a course space were easy. The community coordinator has the access privileges necessary to deal with day-to-day operations.

What’s the lesson? Select tools that match your specific community requirements and context. There is no single ideal community platform, so plan for a good foundation to build as new uses and needs emerge. This example demonstrates that a cost-effective tool does exist that could be used by an instructor, with minimal support from technical experts.

If your community does not have a technical support staff, do not worry. Since your community is interacting over distance, there is no need to host the community site yourself. Just as some face-to-face communities find a public or private space to meet, you and your online community can use public or private web-based spaces for communication, activities, and more. For example, the SCoPE project hosts its own installation of the Moodle learning management system, but different companies can host Moodle for you for a range of fees, depending on how sophisticated you want to get. The following case study discusses another hosted solution.

Case Study: Technology Decisions for BCcampus

As a new organization in 2003, BCcampus was, and remains, a small organization relying on outside partnerships for provision of services (see the BCcampus Case Study above). Providing an online community was really only feasible via an application service provider (ASP) solution where hardware, software, and technical support resources were provided by a host provider.

LearningTimes (based in New York) was chosen as the host provider because of BCcampus staff’s first hand experience in helping launch their LearningTimes.org site and confidence in the underlying technical solution on which their online community services are provided. BCcampus research revealed LearningTimes to be uniquely positioned as an online community provider for the education market and a leader and innovator in the use of online community for education. The online community technology provided by LearningTimes is a customized version of Ramius’ CommunityZero platform. This technology is very robust and provides support for a mix of asynchronous and synchronous capabilities, including: text discussion forums, file posting, contributions area, calendar, live meeting rooms, automatic email updates, integrated instant messenger, photo gallery, polls and surveys, announcements, group email broadcasts, basic chat room, related content, search, admin controls, and more.

With LearningTimes’ help, the first community in the BCcampus network of online communities was configured, branded, and launched within a few short weeks.

Organizing Your CoP

We can think of a CoP in terms of a model of participants and interactions that can guide its implementation. Diagrams of CoP models take a number of shapes, including pyramids, concentric circles and interconnected nodes. To illustrate one possible approach in an education context, we will look at a learning-community model and extend it to a full CoP for researchers, teachers, and students working in a classroom or distance education setting.

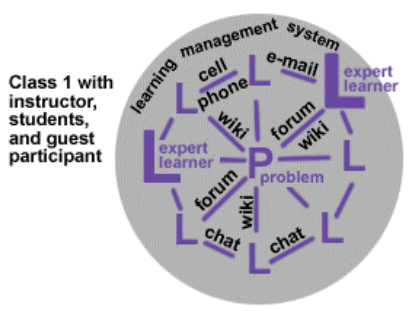

Tom Carroll (2000) suggests a no-boundary model for a classroom-centred learning community consisting of students, teachers, and other resource experts. In this scheme, activity is centred around the problem itself. Teachers become expert learners who actively participate in the learning rather than just guide students from the side. If we apply these concepts to creating an online learning community, we can construct a detailed model (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)) that shows not only the interconnections between the learners and expert learners, but also some of the tools that a learning community might use. Wikis, forums, chat, email, and even cell phones and text messaging can be used. The circle in the diagram is not meant to show an impermeable boundary, but a collaborative space for interaction. In this scenario, a guest participant from another university or organization has access to the learning management system (LMS) space for the course that is attempting to solve a common problem, “P.”

We can extend this model to a full CoP using Wenger & Snyder’s (2001) suggestion of an “overall network structure” with “several layers of participation” centred around the community creators. While their work had an industry focus, there are elements that also apply to learning communities, including layers for charter members, stakeholders, and peripheral community participants, such as the Co-op alumni and Co-op employers. In education, stakeholders might include research grant funding agencies (e.g., CURA), department chairs, college deans, or program assessment coordinators. Peripheral community participants might include support staff and faculty from units, such as the technical support staff at SFU’s LIDC who support SCoPE. Charter members might be the first cohorts of students who joined the learning community, and now they continue to participate even though they have moved to other classes or have graduated from an institution like BCcampus.

Since neither model completely meets our purposes, we can refine our own, original model for communities of practice for online teaching and learning. Wenger & Snyder drew boundaries around the core community members, but Carroll makes a good argument to avoid boundaries. On the other hand, Carroll focuses on just one problem, “P,” while it is more likely that a learning community would focus on a set of problems. Hence, our drawing below depicts several problems for the community to solve within the same topic area, possibly using the concept of subgroups described by Kim (2000). Learners in different subgroups might only address one problem, as depicted here, but some learners are attracted to more than one problem in the overall set. Expert learners are sometimes invited by other expert learners to collaborate. In our model, the instructor works with peer instructors as well as expert learners in a professional organization. Again, the circles in the drawing do not denote boundaries, but environments used for learning community interactions. For coursework, it might be an LMS like Moodle or WebCT, but for a professional organization it might be a different online space with similar tools, such as LearningTimes.

As expert learners working in the online environment, we must make it our job to structure both the inquiry and the collaboration around one or more problems related to our course content. Learners can present their findings to other learners, so the set of problems can be distributed among the group. This is similar to the “jigsaw” cooperative learning strategy in which students in small groups specialize in a portion of the total material, collaborate with students in other small groups who have been assigned the same portion, and then teach the rest of their own group.

The next step is to select tools within the community environment (e.g., Moodle, LearningTimes) that would permit this type of collaborative sharing. It is important to start with tools that you are comfortable using yourself, since you are part of the learning community. Remember that the community can use a variety of tools, though, that might not need your direct interaction. In both Figures 30.2 and 30.3, students use email, cell phones, chat, and other tools to communicate and share with each other. They can use wikis, blogs, and forums to record any thoughts about how to solve the problem, where everyone can see it and respond.

The last steps involve facilitating comprehensive interactions, making sure that no one is excluded due to issues of access or the digital divide, engaging external expert learners and learners alike to participate, pushing the learning community to learn as a group rather than as individuals in the same space, and sharing knowledge and experience with people and groups outside the learning community.

Case Study: Organizing the Small Cities Online Research Community

The LearningTimes platform provides a range of options for public and private designation. One option is to set the community security so that it allows previewing, where visitors are allowed to preview (but not post to) the community before joining. Small Cities community organizers decided instead to create a public, dynamic website, which is currently under development as part of a five-year Community University Research Alliance Grant, called Mapping Quality of Life and the Culture of Small Cities, or “Mapping CURA” for short. This public website will be fed from the databases of Small Cities. So, instead of “preview” mode, they have set the community to “restricted” mode, which allows people who have been invited to join by existing members to participate immediately. However, those who have not been invited must first be approved by the founder or an administrator before gaining access. Their policy is to allow anyone to join who is interested, but they are only granted membership to the general member group.

As well, the LearningTimes platform supports the creation of both public and private spaces among its members. An unlimited number of groups can be established, with each having their own private area for file sharing, discussion, polling, or whatever other activities they wish to pursue. Currently, Small Cities has 17 different groups, each with different privileges.

As of September 2006, the community had 140 members of whom 55 were members of the Mapping CURA group. The LearningTimes platform allows them to easily add groups to the community and to restrict access to areas of the community through group privileges. For example, the major tools (Contributions, Calendar, Articles, Discussions, Databases) each have a folder for Mapping CURA that only members of Mapping CURA can see and access. There are other groups that also have their own areas set aside for their unique group interest. The creation of these subgroups is an important means for allowing the community to evolve naturally than forcing it to conform to a static, predefined structure. As interests are identified with the growth of the community, the evolving design permitted by the LearningTimes platform allows members to quickly access and participate in matters of their direct interest.

For example, a conference was held in Kamloops, British Columbia, called “Artist Statement Workshop”. One of the requirements of the workshop was to submit presentations ahead of time, which could only be viewed by workshop participants. This was to facilitate meaningful discussion at the conference. The LearningTimes platform enabled creation of a group with appropriate folders that only those participating in the workshop could see and access.

As the community grows, new groups can be easily added with a range of different privileges. This enables private space within public space, much as one can do in the physical world.

Maintaining Momentum

Creating a community is only the beginning. To maintain a CoP over time, everyone must keep an eye on common goals or shared themes. Community leaders need to keep the participants’ focus on both short-term and long-term objectives and also need to re-energize the community, when needed, through new postings and events. The entire community also bears responsibility for watching particular dynamics that affect any momentum or growth that a CoP has developed. Foremost among these issues are how people feel about the community, how much time they devote to community activity, and how the community was designed for evolution.

People who participate in a CoP must feel that the community is engaging, responsive, and useful in meeting their needs. The participants must also respect and trust each other and others’ contributions. Otherwise, they are likely to leave the community, never to return.

Members’ time demands can weaken a CoP by restricting their participation. It becomes difficult to deepen knowledge and expertise in an area, as Wenger defines community of practice activity, if members are not interacting on an ongoing basis. Production schedules and academic calendars affect community momentum in different ways. People who are scrambling to meet tight deadlines do not always have time to participate in a community. Conversely, people who work nine-, ten-, or eleven-month contracts have less incentive to continue contributing to a community during the remaining part of the year. They may have to take another job during the down period to make ends meet, or they may take advantage of the lull to take a vacation. This does not mean that your CoP must be so engaging that people participate from Internet cafes near Macchu Picchu, Peru. It does mean that a community may need to adjust its goals to accommodate common fast or slow periods.

As Kim (2000) and others have stated, each community should be built from the start with eventual change in mind. Factors that might precipitate changes include changes for the community members themselves, external events, value changes within the supporting agency, and changes in technology. Whether the community functions in educational or business-related circles, graduation, retirement, relocation, and similar life events may prompt community members to drop out for a while, or indefinitely. Equally important, we need to watch for resistance to a change that might otherwise drive the community forward.

Case Study: Maintaining the Co-op Program Community (Simon Fraser University)

A key element for creating a successful community of practice is to design for evolution. In this case, it is vital to implement design principles that allow for the Co-op Community’s own direction, personality, and enthusiasm to lead the way. The design is non-traditional in the sense that the community’s organization and structure were not predetermined, nor dictated by the developers. Rather than an out-of-the-box vendor solution or onesize-fits-all software product, many of the community’s features are custom-built, based on the needs indicated by the stakeholders.

To ensure the community remains vibrant, a fulltime community coordinator and a community host (a Co-op student) work together to address the emergent needs of the members and to stimulate and encourage interaction. This largely involves open and ongoing communication as well as offering support for those Coop staff members (i.e., Co-op coordinators) who frequently engage with Co-op students.

In this way, the community’s social support systems are designed to create room for growth and cultivation of the online space that allows members to play active roles in shaping its features.