31.3: Verbalizing the Continuum

- Page ID

- 90975

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

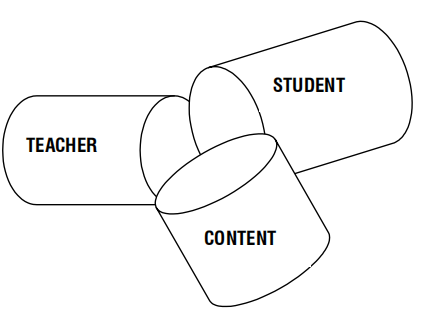

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The video course described above is an example of designing from the perspective of a particular instructional strategy with the intention of supporting a specific learning experience. Attempting to build an online environment to support studio-based instruction was a risk for the instructor, and a leap of faith for the students, but it worked. It was a clear departure from the typical online course design of reading content and posting comments for discussion. It clearly changed the roles for the students and the instructor, forcing both to negotiate tasks, engage in problem-solving, and participate in critiques. While studio-based design is certainly at one end of the continuum that we will discuss later in this chapter, it shares the three constants inherent in all teaching and learning interactions—the intersections of teachers, students, and content.

We became aware of the importance of those intersections in our recent work in a Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) project, Strengthening Capacity for Basic Education in Western China (SCBEWC). There we were called upon to introduce instructional design and develop a distance education system to train teachers in rural, remote regions. However, it wasn’t until one of us was invited to lecture graduate students at Beijing Normal University on the importance of instructional design in the West that we were forced to consider the issue ourselves and share it with others in a way that ensured the key essence was not lost in translation.

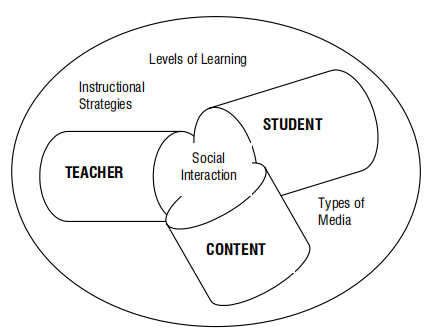

The graduate students at Beijing Normal University were persistent in their demands to understand why the design rather than simply the content of the instruction is important. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) helped scaffold their understanding and provoked an interesting discussion concerning the overlap among the three circles. The importance of social interaction that can be generated when the teachers and learners come together to explore, solve problems, and negotiate the content was also discussed. A plate was added for the three circles to sit on, and it was labelled instructional strategy, levels of learning, and types of media. This diagram helped the students understand that it is the role of the instructional designer to select the strategy that best suits the needs and goals (Vygotsky, 1986) of the three variables (teacher, student, and content).

Right there, in that simple drawing was the crystallization of the authors’ thinking about social constructivism; work that draws on Dewey (1929), Piaget (2002), and Vygotsky (1986). Drawing from our experience, it was easy to share examples of a variety of educational contexts, ranging from training situations in which computer-marked drill and practice was the most appropriate approach to achieve simple certification requirements, to the development of complex simulations and scenarios to encourage higher-order thinking and problem-solving at the graduate level. Figures \(\PageIndex{1}\) and \(\PageIndex{2}\) allowed us to introduce Bloom’s taxonomy for levels of complexity of task design as well as Dale’s Cone of Experience for appropriate media selection as examples of instructional strategies and categories.

Between us, we hold a combined 30-plus years of experience in instructional design, content development, online teaching and consulting; therefore, the linkage between the components of the modified Figure 1, was fairly intuitive. However, it did take the presentation in Beijing to make them tangible. Eisner (1998) is correct when he says, “There is nothing slipperier than thought …” suggesting that capturing thoughts on paper or blackboards helps to make the intangible (thoughts) tangible and therefore editable and discussable” (p. 27). We trust that sharing the figures presented in this chapter will cause you to engage in some activities that will make your thoughts tangible as well. We support Eisner’s belief that it is not until people begin to capture their thinking in a sharable form (text, concept maps, collegial conversations), that it becomes concrete enough to be actionable. Our work in China has forced us to explain things in a clear and concise manner, fit for translation, that we held intuitively, and it has encouraged us to think of the diverse instructional strategies we have seen in various courses, resources and training situations and situate them along a continuum of practice. It has been through that process of sharing our individual knowledge that we have been able to solidify our thinking and enlarge our own community of practice.

The Continuum Story

Both of us have taught instructional design at the graduate level and in workshops. We have developed content for corporate training as well as K–12 courseware. However, our work in China has forced us to synthesize how we present the importance of instructional design to others. Typically, in that work we are introducing the concept of design as a means to an end rather than a process in itself, and more often than not, doing so through a translator, with limited time allotted to the task at hand.

As we work with our Chinese colleagues to develop a system of distance education for 10 million teachers, and eventually 200 million students (China has the largest public education system in the world), the development of a continuum of practice has been helpful. To illustrate a range of increments along that continuum, we developed a table of significant approaches, matched with appropriate software, media, and instruction. Of course, any table such as Figure 31.2 generalizes important concepts and subjects those generalizations to criticism of either omission or over simplification. However our work suggests Figure 31.3 provides a helpful starting place for those considering alternative or innovative approaches to teaching and learning, especially for those new to online teaching and learning.