2.1: Prelude

- Page ID

- 57826

“...model, model, model...” —Patty Cassidy, CCC-SLP

It was a crisp autumn day when I departed my graduate class in augmentative and alternative communication alongside my course instructor Patty Cassidy. It was one of those sublime moments after an inspiring class when you find yourself thinking deeply about the subject matter. I remember innocently enough asking her what she thought was most important about language learning for children who could not use their voice to meet their full daily communication needs. At that point we stopped on the steps of the College’s building and she shared that she thought modeling the communication systems we were using with the children was the most important principle. She tapped me on the shoulder as we were walking away and said, “model, model, model... remember that, Sam.” Walking away inspired from the class session and conversation, I had little idea exactly how important those words and the concept they represent are for the language acquisition process of children who have difficulty speaking. Five years later I found myself defending a Ph.D. dissertation on the subject of teaching adults to model using Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) to help children learn how to use those AAC systems.

I remember finding classic texts on language input and motherese such as Snow and Ferguson (1978) and realizing how long people have been interested in the importance of modeling language interactively to children. The following quote exemplifies the spirit of naturalistic communication interventions.

When asked how a parent might best support a child’s learning of language, Roger Brown (in the introduction to the seminal Snow and Ferguson, [1978, p. 26]) provided the following response: “How can a concerned mother facilitate her child’s learning of language?” His answer was, “Believe that your child can understand more than he or she can say, and seek, above all to communicate. To understand and be understood. . . . If you concentrate on communicating, everything else will follow.” The research on communication interventions for children with disabilities impacting their ability to communicate provides evidence that these same high expectations and the use of AAC modeling based interventions can produce benefits for individuals with CCN. The challenge is how to better provide a rich communication environment full of models of language, engagement, high expectations, and opportunities for participation. When these conditions are provided, there is good reason to think that the learning of language “. . . will follow.”

This chapter introduces AAC, shares select intervention resources, and then introduces a naturalistic AAC intervention strategy, MODELER.

What Is AAC?

Child language development is impacted by the interaction of the child’s abilities in all domains such as motor, vision, hearing, and language (Siegel & Cress, 2002). For individuals with disabilities that impact their ability to meet their daily communication needs using speech, language acquisition can be empowered through providing access to Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2013).

AAC Definition

“AAC includes all forms of communication (other than oral speech) that are used to express thoughts, needs, wants, and ideas. We all use AAC when we make facial expressions or gestures, use symbols or pictures, or write. People with severe speech or language problems rely on AAC to supplement existing speech or replace speech that is not functional. Special augmentative aids, such as picture and symbol communication boards and electronic devices, are available to help people express themselves. This may increase social interaction, school performance, and feelings of self-worth. AAC users should not stop using speech if they are able to do so. The AAC aids and devices are used to enhance their communication.” American Speech-Hearing Association, retrieved from: https://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/AAC/.

There are many first-hand accounts of individuals who have found alternate ways to communicate (Brown, 1964; Creech, 1992; Koppenhaver, Yoder, & Erickson, 2002). As a whole, their writings, combined with research documenting efficacy express the message that despite not being able to speak, it is possible to become a competent communicator by utilizing AAC (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2013, Romski & Sevcick, 1996).

The goal of AAC, described by Porter (2007), is to give people the ability to meet socially valued daily language needs efficiently, specifically, intelligibly, and independently. This is accomplished both through using AAC tools and by providing AAC intervention and training to support the individual using AAC.

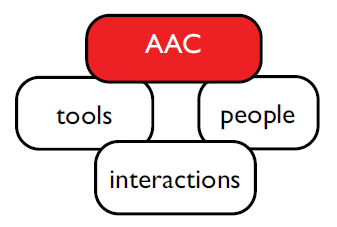

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): AAC is a set of tools people use for interactions and learn to use through

interactions.

One fear many parents and professionals have is that by using AAC system components to assist in communication, the child’s speech development will be impeded. Fortunately, this is not the case. Evidence suggests that AAC not only does not impede development, but may even support speech development (Millar, Light, & Schlosser, 2006). Parents, teachers, and therapists also may be concerned about prerequisites for commencing AAC interventions, but as Cress (2002) points out, there are no prerequisites for AAC.

Communication and Language

Communication is sending messages. Language is the coded system of symbols with agreed-upon patterns and rules that enables a community of people to interact and communicate with each other and to efficiently send messages (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2013). There are important social purposes of communication such as (a) expressing needs and wants, (b) feeling social closeness, (c) sharing information, (d) fulfilling established conventions of social etiquette (Light, 1988) and (e) engaging with oneself in an internal dialogue (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2013). Communicative competence is not necessarily an inherent trait, but something that must be learned and scaffolded. Communicative competence can be organized into linguistic, operational, social, and strategic domains (Light, 1989).