1.2: Struggle and Protest for Chicanx and Latinx Studies

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138182

- Melissa Moreno & Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Historical Roots of Ethnic Studies

There is no singular origin of Chicanx/Latinx studies or a set of scholars who wrote the field into existence. But there are traces of beginnings and aspirations reflected in key documents like the Plan de Santa Bárbara published in 1969 by student activists in California, the Plan de Aztlán published by student activists at the first Chicano Youth Conference in Denver, Colorado, and the goals of the first Chicana/o studies programs in California and Puerto Rican (Boricua) studies programs on the East Coast. Civil rights and labor movements like the United Farm Workers of America, and high school Student Walkouts took place throughout the Greater Southwestern states before Chicanx studies appeared at colleges and universities. More about the history of Chicanx and Latinx studies will be addressed in Chapter 3: History and Historiography and Chapter 8: Education and Activism. Scholars sometimes associated with Chicanx and Latinx studies are Rudy Acuña, Sonia E. Alvarez, Gloria Anzaldúa, Yarimar Bonilla, Antonia Castañeda, Teresa Córdova, Adelaida Del Castillo, Juan Flores, Juan Gómez-Quiñones, Elizabeth “Betita” Martinez, Walter Mingolo, David Montejano, Cherríe Moraga, Sylvia Morales, Carlos Muñoz, Ana NietoGómez, Chon A. Noriega, Mary Pardo, Américo Paredes, Emma Pérez, Beatriz Pesquera, Aníbal Quijano, Adela Sosa Ridell, Mérida M. Rúa, Vicki L. Ruiz, Chela Sandoval, Rosaura Sanchez, Carmen Teresa Whalen, and Patricia Zavella, among others. While many Chicanx and Latinx studies intellectuals have worked as activist scholars with formal training, others have developed their scholarship as organic intellectuals, a concept that refers to individuals who gain advanced expertise through hands-on experience, working directly with community members. Collectively, this work offers an understanding of the world from the eyes of Chicana/o/xs and Latina/o/xs. Chicanx and Latinx studies emerged from the struggles and long histories of communities of color and Indigenous peoples who value education for its potential to transform lives, inspire change, raise awareness, and disrupt systems of power and exploitation. But how is Chicanx and Latinx studies connected to ethnic studies?

Ang hindi lumingon sa pinanggalingan ay hindi makakarating sa paroroonan. (A person who does not look back to where he came from would not be able to reach his destination.) — Proverb by Dr. Jose P. Rizal, National Hero of the Philippines

This proverb is understood by ethnic studies educators to mean, “No history, no self. Know history, know self,” and it reflects Dr. Jose Rizal’s leadership in the Filipino Revolution against Spanish colonization. Although the statement was made halfway around the world away from the homelands of Chicanx and Latinx communities, it and the larger struggle for justice and decolonization resonate with the historical roots of Chicanx and Latinx studies, along with the larger field of ethnic studies. Decolonization refers to the various struggles led by Indigenous people for land, sovereignty, self-determination, and a transformation of the ongoing conditions of colonial power. Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island (a name for North and Central America used by some Indigenous peoples of the western hemisphere) have practiced educational pedagogies that center reciprocity, mutual respect, and interdependence long before the creation of Chicanx and Latinx studies as an academic field. Traditional knowledge that has been sustained and carried forward in the face of settler colonialism provides vital insight into the importance of activism and strategies of resistance against oppressive systems.6 Settler-colonialism refers to the specific forms of colonialism in which outside powers attempt to eradicate and replace the living societies of Native people to establish and maintain settler societies. Importantly, settler-colonialism is a structure, not an event. This means that it is an ongoing system like racism and sexism, not a historical moment that is relegated to the past.

The introduction of colonial education led to the attempted erasure and genocide of Indigenous lifeways. For example, the missions in California, which were first established in 1769, served as central institutions of enslavement and labor for Catholic priests to coerce Indigenous peoples to adopt Christianized belief systems, traditions, and language. Missions disrupted Native American families and prevented family formation and transmission of cultural knowledge. Similarly, in 1869 the U.S. government and Christian churches began systematically kidnapping Native American children and trafficking students into government and church-run boarding schools, which were designed to forcefully strip students of their Native American beliefs and practices by imposing the English language, Christian religious customs, and colonized modes of dress, effectively destroying their tribal values, knowledge, and identity.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the United States greatly expanded the role of public education in daily life. This infrastructure was built up unequally, with schools actively segregated by race and socio-economic status. The separation of students by race helped to reinforce the existing racial hierarchy in the broader society, providing legitimacy and justification for prevailing dominant ideologies. In Chapter 8: Education and Activism, you will learn more about the history of activist and legal challenges to segregation and the relationship between this work and the field of Chicanx and Latinx studies. The roots of current-day ethnic studies are connected to the ongoing resistance to oppressive educational systems such as these.

Early Days: Ethnic Studies, Chicano Studies, and Chicana Studies

Throughout the 1960s, colleges, and universities were the sites of student-led protests for racial justice, environmental justice, gender liberation, and in opposition to the war in Vietnam. It is in this context that Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale met at Merritt College in Oakland, California, where they were inspired by the writings of the Black Martinican radical author Frantz Fanon. They began a student group called Soul Students Advisory Council and advocated for the first Black studies program before founding the Black Panther Party. At the same time, similar efforts were underway throughout California and across the country. The Black Student Union at San Francisco State College (SFSC) was started in 1963 by activists who had trained with the Black Panther Party and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which included Chicanx students. SNCC was a youth-led movement in support of racial justice and civil rights that regularly collaborated with other major leaders and groups working for civil rights and human rights. The organization supported the small minority of Black students at SFSC at the time and sought to increase enrollment. In 1966, Jimmy Garret from SNCC arrived on campus to mobilize and organize Black students. The earlier Freedom Rides in 1961 and the 1968 East L.A. Walkouts inspired many individuals to join these movements, as they both emphasized the importance of access to education in the larger context of racial justice and civil rights.8 You will learn more about this history in the context of education in Chapter 8: Education and Activism.

At SFSC, some of the administration allowed students to teach each other courses not included in the traditional curriculum through the Experimental College. Students resisted any attempt to control the content of these courses, including control over who would be the invited speakers. The culture and operations of the Experimental College attracted radicalized Black students. Students, especially leaders in the Black Student Union, used the Experimental College to build the Black studies curriculum. By 1968, the Black studies curriculum covered history, social sciences, and the humanities, including courses like Sociology of Black Oppression, American Institutions, Culture in Cities, Composition, Modern African Thought and Literature, Recurrent Themes in Twentieth Century Afroamericano Thought, Creative Writing, Avant-Garde Jazz, Play Writing, and Black Improvisation.9

The Longest Student Strike

🧿 Content Warning: Physical Violence. Please note that this section includes discussion of physical violence, including police violence against people of color.

George Murray was a beloved English instructor at SFSC who was known for his vocal critiques of racism and the Vietnam War. He also served as the Minister of Education for the Black Panther Party. After he was fired on November 1, 1968, student leaders from the Black Student Union (BSU) and Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) started a strike. The TWLF was a multi-ethnic coalition of students that were awoken to the fact that they were being taught in ways that were dominating and irrelevant to themselves.10 It included a coalition of the BSU, Latin American Student Organization (LASO), Intercollegiate Chinese for Social Action (ICSA), Mexican American Student Confederation, Philippine (now Pilipino) American Collegiate Endeavor (PACE), La Raza, Native American Students Union, and Asian American Political Alliance. Supporting this coalition were white students as well. These movements built on intergenerational traditions of protest and advocacy that informed the emergent groups that formed, established, and nurtured ethnic studies.11 This led to the formation of a comprehensive list of demands to the college.12 Penny Nakatsu was one of the strike’s leaders at SFSC. Her speeches emphasized the importance of connecting student oppression with U.S. imperialism and militarism that creates adverse conditions throughout Third World countries. Nesbit Crutchfield was also a prominent leader in the organization and the first striker to be arrested. He spent over a year in jail and others were jailed too.

Police officers used militarized tactics on strikers, including directly assaulting students with batons, water hoses, and other weapons. SFSC’s President at the beginning of the strike, Robert Smith, was sympathetic to students and interested in hearing out their demands. However, the administration quickly replaced President Smith with Samuel Ichiyé Hayakawa, who represented the interests of the predominantly white California State College Board of Trustees, along with then California Governor Ronald Reagan. The TWLF made a conscious choice in its organizing to center the leadership of students of color. However, the strike also garnered support from white students and community members, as well as the faculty union, a local chapter of the American Federation of Teachers. The strike lasted for nearly five months and at its peak, had halted nearly all classes and college operations. Although the protestors were met with hostility, resistance, arrests, and violence, they countered this with a strategy called the “War of the Flea,” which focused on disruptive tactics that would pressure the administration to take action. For example, protestors checked out massive amounts of books from the library, disrupted classes to encourage students to join the strikes, and staged massive public demonstrations with music and chanting.13

Outcomes of the Strike

In the end, the strikers won nearly all of their demands, including the creation of a Black studies Department, the funding of 11.3 new full-time equivalent faculty positions, a new Associate Director of Financial Aid, the creation of an Economic Opportunity Program (EOP) with 108 students admitted for Spring 1969 in this program, as well as 500 seats committed for non-white students in the Fall of 1969 with 400 additional slots for EOP students, and a commitment to creating the School of Ethnic Studies.14 The School of Ethnic Studies later became San Francisco State University’s College of Ethnic Studies, which includes Africana studies, American Indian studies, Asian American studies, Latina/Latino studies, and Race and Resistance studies. The strikers’ unmet demands included that Dr. Nathan Hare and George Murray be reinstated as faculty in the newly formed Black studies program. Despite these losses, to this day, the strike remains the longest student strike in U.S. history and is a testament to the power of student mobilization.15

The tenacity of the strikers inspired students at the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) to form their own Third World Liberation Front in January 1969, who began a separate strike for ethnic studies at UCB.16 Strikers called for a Third World College, but the administration ultimately formed a Department of Ethnic Studies. Chicanas/os who were TWLF members included Lucha Corpi, Larry Trujillo, Francisco Hernandez, and others.

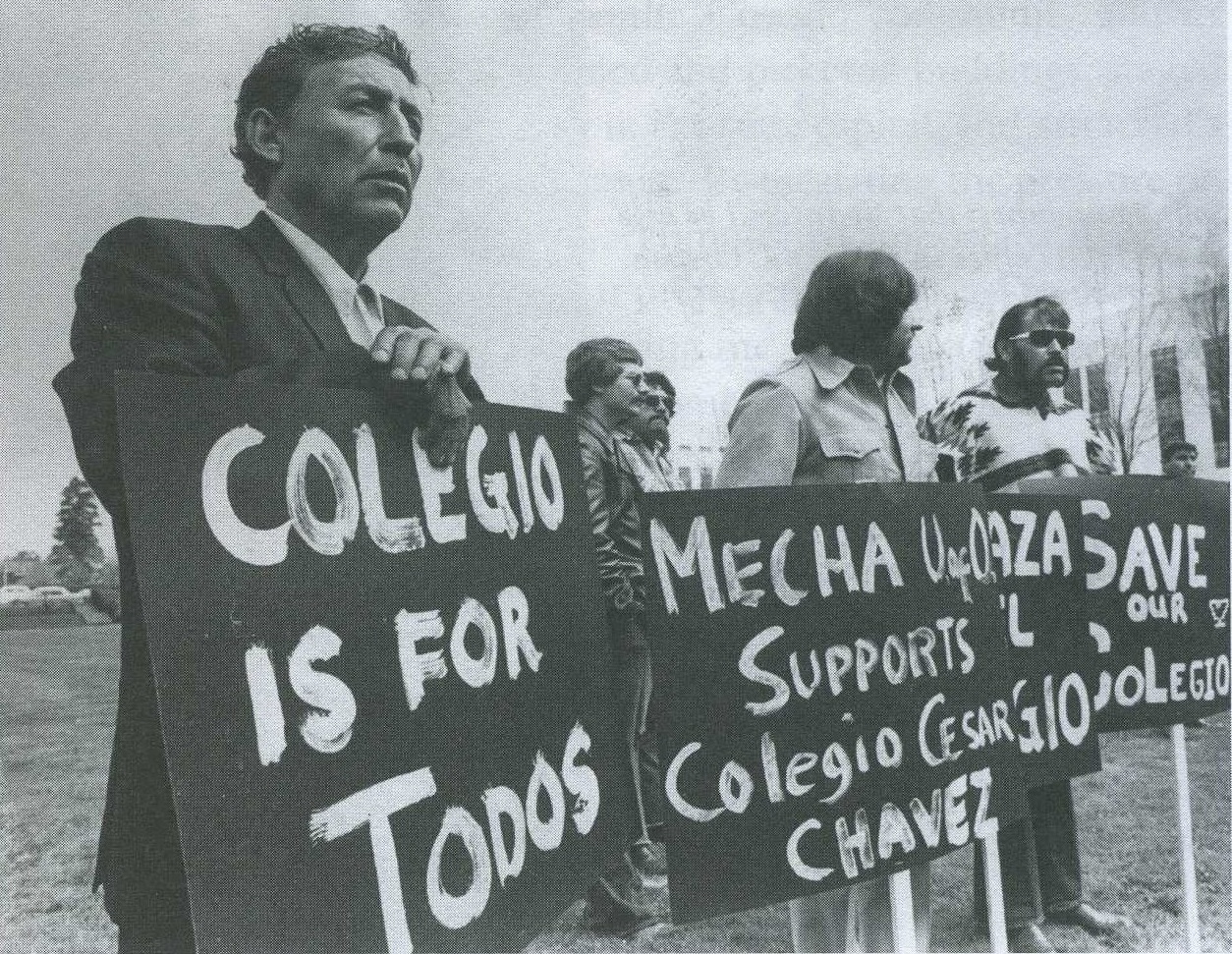

Throughout the country, racial justice and student activism were front and center, leading to a cascade of activism for ethnic studies programs, including the core disciplines of Black studies, Chicano studies, Asian American studies, and American Indian This momentum was built through grassroots movements, such as those created by the United Farm Workers of America (since 1962),17 ethnic studies (1968), and Chicano Youth Conference (1969).18 Building from this work, Chicana/o/x activists came together at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) and published El Plan de Santa Barbara, a document that united diverse activists from around the state of California and laid out a roadmap for Chicana/Chicano studies. Of equal importance to new areas of academic scholarship were programs to increase the retention, engagement, and success of students from minoritized backgrounds. Various chapters of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA, now Movimiento Estudiantil Chicanx de Aztlán) advocated for equity and justice in higher education, such as the protestors in Figure 1.2.1, who are shown supporting Cesar Chavez College. In response to this type of student activism, UCSB created the first Chicano Studies Department in the University of California in 1970, now Chicana and Chicano Studies, and eventually formed the first Ph.D. program in the field in 2003. California State University, Los Angeles, was also a forerunner in this area, establishing a Mexican American studies program in 1968, which became the Department of Chicano Studies in 1971, and is now called the Department of Chicana(o) and Latina(o) Studies.

Growth and Expansion of Chicanx/Latinx Studies

Scholarly Associations and Research

Scholarly associations are voluntary organizations of professional researchers who organize the exchange of ideas through activities like conferences where scholars present and share their work, newsletters, peer-reviewed publications, scholarships, and research grants. Within Chicanx/Latinx studies, multiple scholarly organizations exist that focus on specific disciplines and populations of scholars.19

The National Association for Chicano Social Scientists was formed in 1972 and renamed the National Association for Chicano Studies in 1973. To recognize the contributions of mujeres (women) it changed its name to the National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies (NACCS) in 1995, which remains the name today. You can learn more about this history in Chapter 5: Feminisms. To address the diversity of identity politics and conditions, NACCS created various caucus groups. They include Chicana, Graduate Student, Jotería, Indigenous, Lesbian Bisexual Mujeres Transgender (LBMT), K-12, Student, Community, and Labor. A sister organization of NACCS that emerged called Mujeres Activas en Letras y Cambio Social (MALCS), was founded in 1982. It focuses on Chicana/Latina and Indigenous feminist scholarship separately from what was known at the time of its founding as the National Association for Chicano Studies (now NACCS). Some MALCS members established the Society for the Study of Gloria Anzaldúa. Similarly, after years of collective work, organizing, and tension within various caucus groups focused on gender and sexuality within NACCS, in 2011, scholars formed an independent group called the Association for Jotería Arts, Activism, and Scholarship (AJAAS).This focuses on intersecting issues centered around sexuality, gender, and power and is discussed in more depth in Chapter 6: Jotería Studies. Even more recently, in 2014, the Latina/o Studies Association was also formed. This group focuses on the global community of scholars in Latina/o/x studies.

Academic associations encourage student participation and have specific opportunities and scholarships available to students in the field. There are also associations within other disciplines that utilize a racial justice lens or are focused on Chicanx and Latinx communities such as the Latino Caucus of the American Public Health Association, National Latino Behavioral Health Association, Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS), and the American Sociological Association Section on Latino/a Sociology. Importantly, not all of these organizations and not all groups focused on Latin American and Latinx origin communities reflect the same values, principles, and methods of Chicanx and Latinx studies. For example, fields like Latin American studies and Central American studies focus on the distinctive societies, cultures, politics, and peoples of Latin America and Central America. These areas originally grew out of coordinated political work to counter liberation and self-determination movements in these regions. However, over time, younger scholars in the field have come to recognize and collaborate with progressive scholars and work in the community. This approach may appear in American studies and cultural studies, as well as in social sciences and humanities disciplines. This typically does not include a commitment to transformative social change through engaged scholarship and relevant pedagogies, which is a core principle of Chicanx/and Latinx studies, as well as ethnic studies.

Non-academic organizations that have been important to the scholarly associations and social movements, civil rights, and development of leadership associated with Chicanx and Latinx struggles have included Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), California Latino School Board Association, California Latino Legislative Caucus, and California Latino Caucus, and the bi-national organization Frente Indígena de Organizaciones Binacionales (FIOB), which serves Indigenous Latinx migrant and non-migrant communities across California and Mexico. Chicano Latino Youth Leadership Project and Future Leaders of America are two youth-based organizations that have been involved with the work of Chicanx and Latinx studies.

Growth and Institutionalization

Chicanx and Latinx studies provide an excellent opportunity for students to deepen their knowledge and passion for meaningful topics related to their lives and communities for the purpose of social change. Research shows that Chicanx/Latinx studies classes, like other ethnic studies courses, have academic and social benefits for all students, as well as campus communities as a whole.20

In an urgent response to the ongoing miseducation and underrepresentation of historically racialially marginalized students in school curriculum, there have been calls to mandate an ethnic studies requirement in high schools and colleges. Legislative activism is evident in the passage of California Assembly Bill 101 and Assembly Bill 1460, Oregon House Bill 2845/2023, and Texas House Bill 1504-2021-22.

In California, faculty advocates and administrators established ethnic studies as a general education graduation requirement in California high schools, the California Community College (CCC), the California State University (CSU), and the University of California (UC) systems. Assemblymember Shirley Weber, the author of AB 1460, and faculty advocates are displayed in Figure 1.2.2. This bill was passed in 2020 and built on the work of Assemblyman Luis Alejo.

AB 1460 changed the general education curriculum to include ethnic studies as a graduation requirement for all 23 campuses in the CSU system, separate from any diversity or multiculturalism requirements. The CSU enrolls nearly half a million students (485,550 in 2022), and it is the largest public research university system in the world. AB 1460 acknowledges ethnic studies as made up of distinct academic fields, one of which is Chicanx and Latinx studies. The California Community College Ethnic Studies Faculty Council (CCCESFC) and allies followed their CSU colleagues by advocating for a CCC ethnic studies graduation requirement, resulting in changing the Title V legislative code. In addition, the UC Ethnic Studies Faculty Council with the system-wide Academic Council is in the process of establishing both an ethnic studies graduation requirement and an admission requirement for high school students planning to attend the UC.

Chicanx and Latinx studies curriculum has a long history in the K-12 educational context as well. In 2014, El Rancho Unified School District in Pico Rivera, California, created a high school requirement for ethnic studies. The Ethnic Studies Now Coalition helped to spread the movement to other high schools through advocacy and sharing resources. With more and more districts adopting ethnic studies, statewide advocates in California moved to formalize the curriculum and establish a framework for ethnic studies teachers, including Chicanx and Latinx studies. Further, in conjunction with the growth and institutionalization of ethnic studies, AB 1703 passed in 2022 in California to establish the California Indian Education Act and encourages school districts, county offices of education, and charter schools to form California Indian Education Task Forces with California tribes local to their regions or tribes historically located in the region, in order to develop model curricula related to Native American studies. This legislation is a reminder that ethnic studies cannot, and should not, be taught without advancing the present and past realities of Native American peoples.

Campus programs like the UCLA Center X / Teacher Education Program, Exito at UCSB, and professional development organizations like XITO (Xicanx Institute for Teaching and Organizing), Acosta Educational Partnership, and Liberated Ethnic Studies have started to train educators interested in working in this growing field. Likewise, Assembly Bill 1255, authored by Wendy Carrillo, calls for the creation of a statewide task force to provide a report on the creation of a single-subject credential in ethnic studies because it does not yet exist. Currently, the social science credential does not prepare teachers with the content and pedagogical training needed to teach ethnic studies. In May 2022, Assemblymember Jose Medina argued this very point to the California Department of Education teacher credential leadership. To augment this gap in California teacher credentialing, educators at Fullerton College have created an Ethnic Studies for Educators certificate program, which is the first of its kind in the community college system and will provide current and future teachers with disciplinary training in ethnic studies that can be applied to K-12 teaching.

This moment is an opportunity for educators at all levels to embrace, honor, and respect the contributions and social movements led by Latinxs and other communities of color in the state and nation, along with other issues championed by diverse marginalized groups. Long before the beginning of ethnic studies as a formal discipline in the 1960s, communities have been calling for relevant, responsive education that communicates the truth of historical, political, social, and cultural systems. This has implications for early childhood education, K-12, and higher education. As of the writing of this book, these are pressing and current political-educational issues being addressed in California and throughout the country.

Threats Against Chicanx/Latinx Studies

While Chicanx and Latinx studies scholarship and curriculum have experienced substantial growth over 50 years, the field has always been threatened by counter-movements and institutional resistance. In 1998 in Tucson, Arizona, the school district established a Mexican American studies program that grew to 48 course offerings and was the largest ethnic studies program in any school district nationwide. The department offered student support and facilitated teachers’ and parents’ involvement in Chicana/o/x and Latina/o/x student success, which directly increased graduation rates and grades in all classes. In 2010, state lawmakers passed Arizona House Bill 2281, which dismantled the program and banned a range of related books from any classes in the state. In response, activists in Arizona organized a book-ban caravan to California, inspiring California ethnic studies faculty and advocates from ethnic studies, forging greater solidarity across state lines. Figure 1.2.3 shows protesters in June 2011 supporting the Tucson Unified School District's Mexican-American Studies program. This protest cultivated the will for change and supported activists engaged in drawn-out legal battles over the legislation. Eventually, the ban was overturned in 2017, as it was deemed racist and unconstitutional.

Figure 1.2.3: “Arizona Ethnic Studies” by Arizona Community Press, Wikimedia Commons is licensed CC BY-SA 4.0

The anti-ethnic studies rhetoric from the Arizona law, which claimed to restrict teachers from promoting “resentment toward a race or class of people" or advocating “ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals,” re-emerged in 2021 as conservative activists strategically conflated ethnic studies and Critical Race Theory. They falsely made it seem like they were interchangeable. Critical Race Theory is a legal perspective that examines the relationship between U.S. laws and systemic racism, with a particular emphasis on how to end racial bias. Ethnic studies, by contrast, is an interdisciplinary field of study that encompasses a wide range of topics, issues, and perspectives focused on the lived experiences of historically defined racialized groups. Legislators have passed statewide bans on Critical Race Theory to intimidate K-12 educators who discuss race and ethnicity in their classrooms in any format, including ethnic studies. Despite this political hostility and counter-mobilization, ethnic studies educators and others invested in student equity and success continue to work at the front lines to inspire students and ensure that the next generation has access to a relevant education.

As California continues to formalize and institutionalize ethnic studies, scholars and activists are contending with the boundaries of the field and its purpose for higher education and society. With the inclusion of ethnic studies in general education requirements, courses in Chicanx/Latinx studies will receive a greater amount of institutional oversight, and an increased number of students gaining from this content and pedagogy. However, this has created an incentive for faculty from outside disciplines with no training in Chicanx/Latinx studies or ongoing work in the field to enter the discipline as instructors or researchers. While many fields address topics related to ethnicity, race, politics, culture, and society, expertise in the traditions and practices of Chicanx and Latinx studies is based on disciplinary training and a sustained commitment to racial justice through action.

Footnotes

6 Michelle M. Jacob Leilani Sabzalian, Joana Jansen, Tary J. Tobin, Claudia G. Vincent, and Kelly M. LaChance, “The Gift of Education: How Indigenous Knowledges Can Transform the Future of Public Education,” International Journal of Multicultural Education 20, no. 1 (2018): 157–85, https://doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v20i1.1534.

7 For discussion about Missions from California Native read A Cross of Thorns: The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions by Elias Castillo and review https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dmarnR8sgNE&t=38s

8 Ziza Joy Delgado, “The Longue Durée of Ethnic Studies: Race, Education and the Struggle for Self-Determination” (PhD Dissertation in Ethnic Studies, UC Berkeley, 2016), https://escholarship.org/uc/item/84n3f8kh.

9 Fabio Rojas, From Black Power to Black Studies: How a Radical Social Movement Became an Academic Discipline (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010).

10 Daryl Maeda, Rethinking the Asian American Movement (New York: Routledge, 2011).

11 Delgado, “The Longue Durée of Ethnic Studies.”

12 List of demands from the BSU and TWLF can be found https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/st...bundles/187915

13 Rojas, From Black Power to Black Studies.

14 Rojas, From Black Power to Black Studies.

15 Delgado, “The Longue Durée of Ethnic Studies”; Maeda, Rethinking the Asian American Movement; Rojas, From Black Power to Black Studies.

16 Delgado, “The Longue Durée of Ethnic Studies.”

17 The UFW was established in 1962, long before Chicano Studies, by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta with the aid of Fred Ross, Marc Grossman, and Filipino farm worker leader like Itlong and Vera Cruz too. Chicanx and Latinx college students developed their leadership in the UFW and brought it to the Walkouts and call for Chicanx studies too.

18 The first Chicana/o Youth Conference was held in 1969 after the Walk Outs and the Ethnic Studies Student Strike. https://www.kcet.org/history-society...nited%20States.

19 Content in this section was adapted from “The Ongoing Struggle for Ethnic Studies” by Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick in Introduction to Ethnic Studies (LibreTexts), which is licensed CC BY-NC 4.0.

20 Sleeter, Christine E. “The Academic and Social Value of Ethnic Studies.” Washington, DC: National Educational Association (NEA), 2011.