10.1: Chicanx and Latinx Identities and Culture

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138291

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Frameworks for Cultural Analysis

Culture is a system of shared meaning. This includes the narratives, beliefs, behaviors, norms, and customs that establish a group and interact with identity, political structures, and social life. Some examples of culture are language, art, music, food, religion, ceremonies, and more. Within this broad understanding of culture, the “media” is a significant institution that includes various groups who professionally create content. Similarly, pop culture (or “popular culture”) refers to those cultural practices that are produced and distributed for mass audiences. Historically, studies of culture and society have focused within rigid boundaries, such as focusing only on the elite culture of “high culture.” However, this ignores critical components of cultural practices and the people who carry them out.

In the context of Chicanx and Latinx studies, Frederick Aldama defines pop cultura analysis in terms of “our everyday lives, scholarly inquiry, and knowledge dissemination. Not all pop culture is made equally—especially when it comes to matters of race, sexuality, gender, and differently abled subjects and experiences.”1 Chicanx and Latinx communities often find and claim representation in pop culture, as it creates opportunities to identify with individual experiences. Through representation, communities create their own sense of self and agency and are better equipped to resist the oppressive narratives imposed on them by the dominant culture.

Given the prevailing norms of white supremacy and settler-colonialism present in dominant media, engagement in pop culture can bring about challenges to one’s perceived authenticity. This is especially true with respect to Indigenous identity and a connection to one’s cultural heritage. For example, Mintzi Auanda Martinez-Rivera notes, “Many scholars and the general public consider that Indigenous persons cease to be Indigenous if they partake in modernity (broadly construed). In this regard, popular culture, as a product of modernity, commodification, consumption, and mass media, is often considered antithetical to the experiences of Indigenous peoples.”2 However, rather than focusing on false distinctions between high and low culture, we can follow, “the Gramscian approach, [in which] popular culture is a ‘site of struggle between the ‘resistance’ of subordinate groups and the forces of ‘incorporation’ operating in the interests of the dominant groups.’”3

In addition to engagement with mainstream culture, Chicanx and Latinx communities have resisted exploitation and exclusion by creating unique cultural forms and content. In the 1960s, this was the main focus of the Chicano Renaissance, an era of cultural flourishing that corresponded to the movements for justice, equity, and civil rights that were central to the political climate of the era. This time included the celebration of the unique cultural strengths of Chicanx communities, including melding English and Spanish (Spanglish), bold artistic styles, and literary themes that explored the complexity of Mexican American identities.

This chapter builds from a broad conceptualization of culture to take a broad approach to Chicanx and Latinx Cultural Productions. This includes works that are by Chicanx and Latinx artists and creators, regardless of the specific subject matter. Content producers range from large-scale films, television programs, radio shows, and performances to the everyday work of Chicanx and Latinx people to create meaning and carry on traditions through daily tasks. Chicanx and Latinx cultural productions also include work that is intended for or claimed by Chicanx and Latinx audiences. Marketing professionals have been emphasizing the benefits of dual-language marketing, including the existence of over 60 million Latinxs, with a median household income of $55,658.4 Media catered to Latinxs have a wide reach into mainstream audiences, including Selena (film), The George Lopez Show, American Family, and Dora the Explorer. Finally, Chicanx and Latinx cultural productions also include media produced about Chicanx and Latinx groups, characters, and stories.

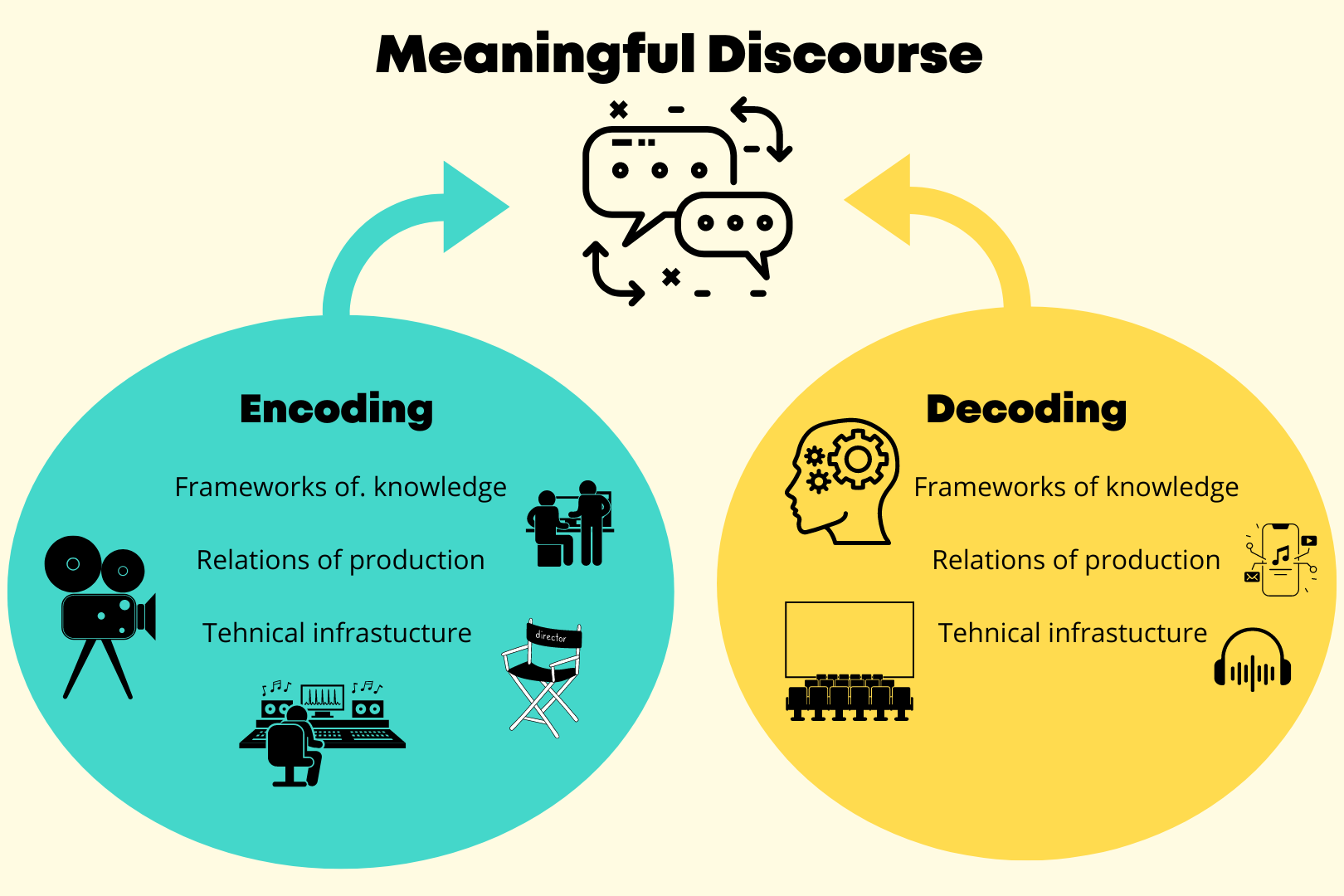

Encoding and Decoding

Black cultural studies scholar Stuart Hall developed a framework for cultural analysis that focuses on the processes of encoding and decoding.5 Encoding and decoding is an information transmission process that creates frameworks of knowledge. This includes interpersonal and institutional processes that produce a nuanced relationship between subjects and their perspective and interpretation of the world around them. Encoding refers to the process of constructing meaning in creating culture. This refers to the producers, writers, artists, performers, and others who showcase narratives and cultural scripts. Decoding is the process by which people view, understand, and interpret these stories. Both processes contribute to the “programme as meaningful discourse” and carry with them frameworks of knowledge, relations of production, and technical infrastructure. This is visualized in Figure 10.1.1.

Figure 10.1.1: "Meaningful Discourse" by Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick, Author is licensed CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Content is adapted from Stuart Hall, “Encoding/Decoding,” in Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks, ed. Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas Kellner, Rev. ed, Keyworks in Cultural Studies 2 (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006), 163–73.

Media Analysis in Practice in Ethnic Studies

By examining culture, we can understand and interpret how narratives and meanings impact all aspects of life, including prevailing inequities and opportunities for resistance and justice. One key component of media representation is the creation of stereotypes. These are limited representations of individuals that reduce someone to a negative association with their group status. As stated by Debra Merskin, “stereotypes go beyond obvious manifestations such as name-calling or facile characterizations, rather they drive Latina educational challenges and disparities, contribute to disparate levels of domestic violence, depression, internalized oppression, as well as distressing legal and societal treatment. Hence, understanding media-engendered stereotypical images are, at least in part, responsible for the denial of opportunity for Latinas in their struggle for identity.”6

Controlling Images

Building from the notion of stereotypes, Patricia Hill Collins coined the term controlling images to describe the ways that common narratives about Black women are used to reinforce exploitative and racist systems. For Chicanx and Latinx communities, specific stereotypes have been constructed in response to social, political, economic, and cultural systems. For example, tropicalism is a negative trope that homogenizes Latinx people by focusing on a fixed set of shared traits: bright colors, rhythmic dancing, and darker skin suited to an “exotic” locale. Audiences internalize these images and some resist them, creating a social system that responds to the prevailing constrictions on identity and representation.

A common controlling image used in the media is the Latin Lover. The Latin Lover stereotype is a construction of Latinos as aggressively sexual and exotic. The trope was developed by white actors like Rudolf Valentino, who played Latin characters with a vague accent and no specific cultural or familial ties. In his times during the 1900s, this construction supported the idea of Mexico as a wild place, which legitimized the prevailing policy of the time, incluiding the recent annexation of Texas (1845) and colonization of Northern Mexico. Now, the image remains and creates a set of expectations and biases against Chicanx and Latinx peoples.

Similarly, G. D. Keller identified the range of stereotypes deployed to represent Latinas as love interests to white male protagonists. First, the cantina girl is characterized by ‘‘Great sexual allure,’’ teasing, dancing, and ‘‘behaving in an alluring fashion.” These are hallmark characteristics of this stereotype. This is also a form of sexual objectification, and the narrative of a ‘‘naughty lady of easy virtue.” While the cantina girl is most often presented physically as an available sexual object, the vamp is a trope of an individual who uses their intellectual and devious sexual wiles to get what they want. This poses a threat, counterbalanced by the draw of charisma. The vamp is a psychological menace to anyone who is ill-equipped to handle them. By contrast, the faithful, self-sacrificing señorita is a woman who usually starts out good but goes bad over time. This character realizes she has gone wrong and is willing to protect her love interest by placing her body between the threat intended for him, ultimately becoming a martyr.7

Repeated exposure to these controlling images can create internal distress for Latinxs, leading to mental health challenges, body dysmorphia, low self-esteem, and impaired cognitive performance. They also promote predatory behaviors in the form of dating violence and sexual harassment.8 Similarly, la doméstica (the Latina/o/x maid/nanny) is a persistent media representation and stereotype of Latinas.9 Represented in productions like Devious Maids, Casa de Flores, Down and Out in Beverly Hills, As Good as it Gets, Babel, Spanglish, Will and Grace, Dirt, I Married Dora, Dharma and Greg, Veronica, Closet, My Name is Earl, El Norte, Clueless, The End of Violence, Storytelling, #blackAF, and Family Guy. For example, on the show, Will and Grace, Rosario, played by Shelley Morrison, is a character who raises comical relief and reflects narratives around social class and occupational distinctions. While the reality of Latinas in domestic work is a social reality and an important part of cultural storytelling, the representation in terms of stereotypes is limiting and reproduces systemic inequality. By contrast, on Dirt, Dolores, played by Julieta Ortiz, is an undocumented immigrant from El Salvador who works as a maid for wealthy New Yorkers. As the protagonist, she is politicized and contends with the hegemonic systems that exploit domestic workers. This interrupts the prevailing assumption of marginality among Chicanxs and Latinxs.

Concept Spotlight: Disidentifications

Among the many narratives promoted through the media, culture also consists of the ways that people understand, interpret, critique, and recreate those narratives. The term disidentification comes from the book, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics by José Esteban Muñoz.10 Disidentification refers to the process of situating oneself within a broader cultural narrative while also existing in opposition to that narrative. For example, queer of color subjects may identify with heroic characters in pop culture that have typically been portrayed by white, heterosexual men, but defy and resist associations with patriarchy, white supremacy, and U.S. nationalism. This process reflects the stakes of both survival and resistance for minoritized subjects.

Due to wide-standing biases in media, it is impossible for some minoritized subjects to fully identify with available images and narratives. Disidentification provides an alternative solution. When disidentification is used in performances, it can also expose and critique the problematic dynamics embedded in existing systems of power and control. This approach recognizes and analyzes the importance of race, ethnicity, Indigeneity, gender, and sexuality in understanding social and cultural relations. Queer of color critiques is associated with scholars and critics like Roderick Ferguson, José Esteban Muñoz, Audre Lorde, and Gloria Anzaldúa who have opened up new fields of inquiry through their research and writing on topics affecting Black and Latinx people within the LGBTQ community.

Footnotes

1 Frederick Aldama, “Foreword: Assembling an Intersectional Pop Cultural Analytical Lens,” in Race and Cultural Practice in Popular Culture, ed. Domino Renee Perez and Rachel González-Martin (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2019), ix–xii.

2 Mintzi Auanda Martínez-Rivera, “(Re)Imagining Indigenous Popular Culture,” in Race and Cultural Practice in Popular Culture, ed. Domino Renee Perez and Rachel González-Martin (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2019), 91.

3 Martínez-Rivera, “(Re)Imagining Indigenous Popular Culture,” 95.

4 The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. “Profile: Hispanic/Latino Americans.” HHS.Gov. 2022. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=64.

5 Stuart Hall, “Encoding/Decoding,” in Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks, ed. Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas Kellner, Rev. ed, Keyworks in Cultural Studies 2 (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006), 163–73.

6 Debra Merskin, “Three Faces of Eva: Perpetuation of The Hot-Latina Stereotype in Desperate Housewives,” Howard Journal of Communications 18, no. 2 (April 2007): 133–51, https://doi.org/10.1080/10646170701309890.

7 Gary D. Keller, “Bilingualism, Biculturalism, and the Cisco Kid Cycle,” Bilingual Review/La Revista Bilingüe 28, no. 3 (2004): 195–231.

8 Lori Kido Lopez, “Racism and Mainstream Media,” in Race and Media: Critical Approaches, ed. Lori Kido Lopez (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2020).

9 Yajaira M. Padilla, “Domesticating Rosario: Conflicting Representations of the Latina Maid in U.S. Media,” Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies 13 (2009): 41–59.

10 José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).