10.4: Television and Film

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138294

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Chicanx and Latinx Representation on Screen

When considering the role of Chicanx and Latinx representations on television and in films, Mary Bletrán offers us the concept of image analysis. Image analysis is an approach that is complementary to a variety of research methodologies, and “can illuminate a great deal about a media text’s racial politics, as well as its implied ideological messages about ethnic and racial groups and race relations.”34 To undertake image analysis, we go through the following steps:

- Describe a TV/film character(s) in terms of their most obvious, external representation. How are they presented?

- Identify the meanings, ideologies, and myths associated with those external traits. What does the character mean to the audience?

- Inquire about the narrative significance of this character. Whose story is being told? Which characters are fully developed? And, what is the balance of power between characters?

For example, TV westerns in the 1950s typically displayed Latinxs as one-dimensional stereotypes (for example, Zorro and Tanto). In these performances, Latinx characters were often played by white actors, and they were signified by speaking broken English, being uneducated, and working in a low-paying job. These representations activated myths about the racial status quo and the assumed superiority of whites. In the overall narrative structure, Latinxs were typically not central figures in the storyline, showed little personal development, and were in positions of subservience.

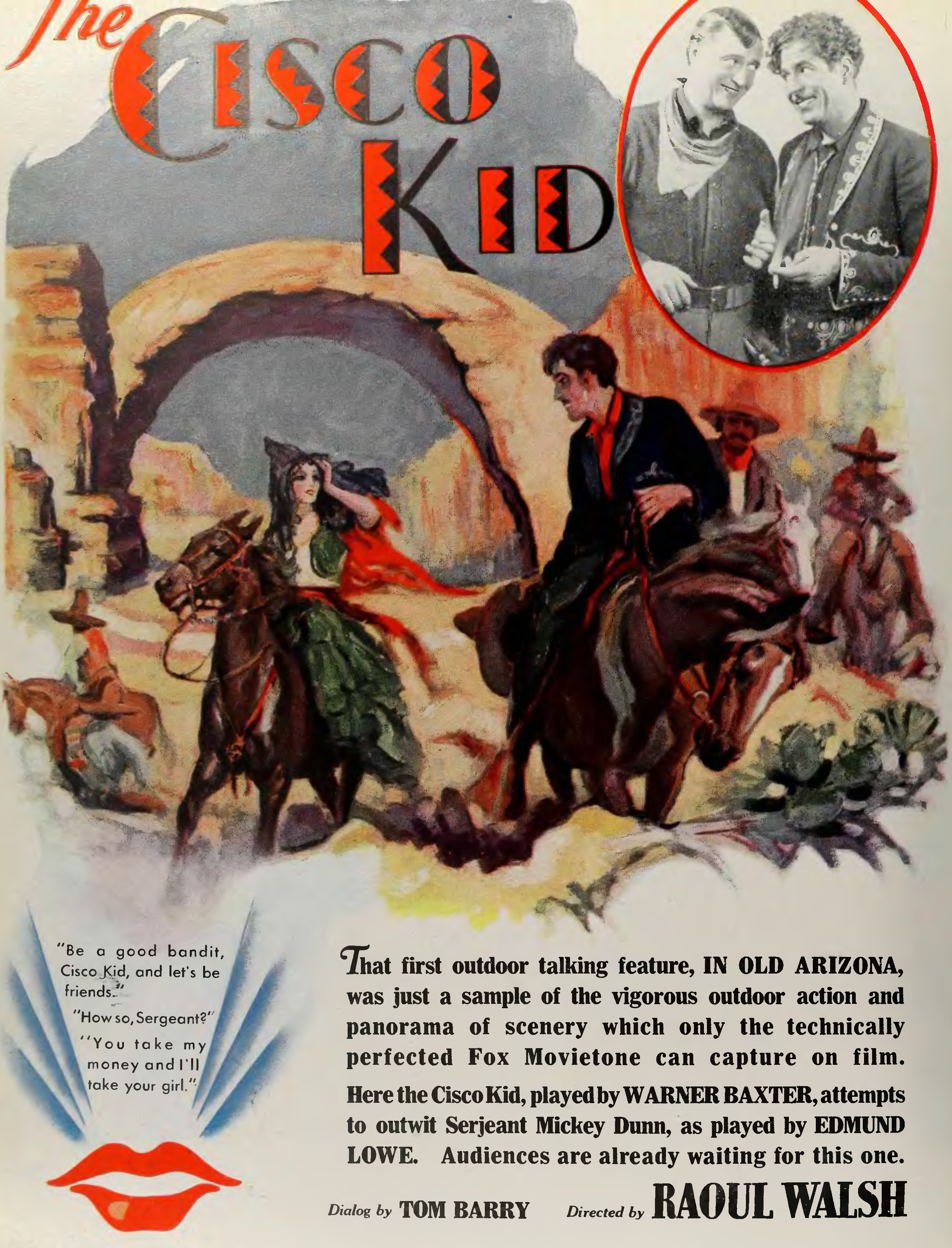

An important counter-example is The Cisco Kid, which ran from 1950-1956, and featured a Latino main character, similar to the other TV cowboys of the era. However, upon further examination, Cisco is still characterized by the racial ideology of the time, with the sidekick character, “Pancho,” who is also Latino, has darker skin, more Indigenous features, and his character is portrayed as less intelligent and important than Cisco. Further, because Cisco was played by Duncan Renaldo (Romanian born American) and Pancho was played by Leo Carrillo (Californian/Spanish), this reinforced the audience’s perception of racial hierarchy through the dynamics of colorism. One of the promotional images for an adaptation of The Cisco Kid is shown in Figure 10.4.1, with the description that reads: “The first outdoor talking feature in Old Arizona, was just a sample of the vigorous outdoor action and panorama of scenery which only the technically perfected Fox Movietone can capture on film. Here the Cisco Kid, played by Warner Baxter, attempts to outwit Serjeant Mickey Dunn, as played by Edmund Lowe. Audiences are already waiting for this one.

Figure 10.4.1: "The Cisco Kid ad in The Film Daily, Jan-Jun 1929" by New York, Wid’s Films and Film Folks, Inc., Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain, CC0.

Since the days of Cisco, we have witnessed many changes in the representation of Latinxs, including new cultural scripts and narratives that Latinx actors and content creators have to navigate. Latina icons are highly recognized Latinas who have achieved a high-level celebrity status. The significance of these individuals for our society can be understood both in terms of their commodification of ethnic authenticity, as well as the symbolic resistance in ensuring representation while still working toward larger goals.35 For example, this is communicated through pop culture figures as diverse as like Salma Hayek, Frida Kahlo, and Jennifer Lopez, as well as characters like Dora the Explorer.

Jennifer Lopez is a recognized film sensation, earning $13 million per movie and drawing huge crowds and audiences to her films. This puts her in a league of elite actors like Salma Hayek, Penelope Cruz, Halle Berry, and Angela Bassett. She has navigated the public perception of her racial and ethnic identity by both emphasizing her identity as a Latina and at times, her proximity to whiteness. Her success as an entertainer in both music and film has given her the opportunity to also take control of her own image and star power, through the clothing, lingerie, and perfume industries and by starting her own production company, Nuyorican Films.36 Figure 10.4.2 shows her singing at the 59th Presidential Inauguration, signaling her esteemed place in American culture and society.

Unlike the New York-born Jennifer Lopez, Salma Hayek gained crossover success in American markets, after establishing her career in Mexican telenovelas. Hayek has played various leading and supporting roles in Hollywood films but has often been limited to roles that are defined by her accent and identity as a Latina.37 In response to the negative pressure she has faced in the industry, Hayek has produced her own films through the company Ventanarosa, which translates from Spanish to English as pink window. Ventanarosa has produced feature films like Frida (2002) and In the Time of Butterflies (2001) and was instrumental in adapting the Colombian novela, Yo Soy Betty La Fea (Ugly Betty) which ran on ABC for 4 seasons (2006-2010). In Figure 10.4.3, Hayek is shown at San Diego Comic Con in 2014.

Figure 10.4.3: “Salma Hayek” by Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons is licensed CC BY 2.0.

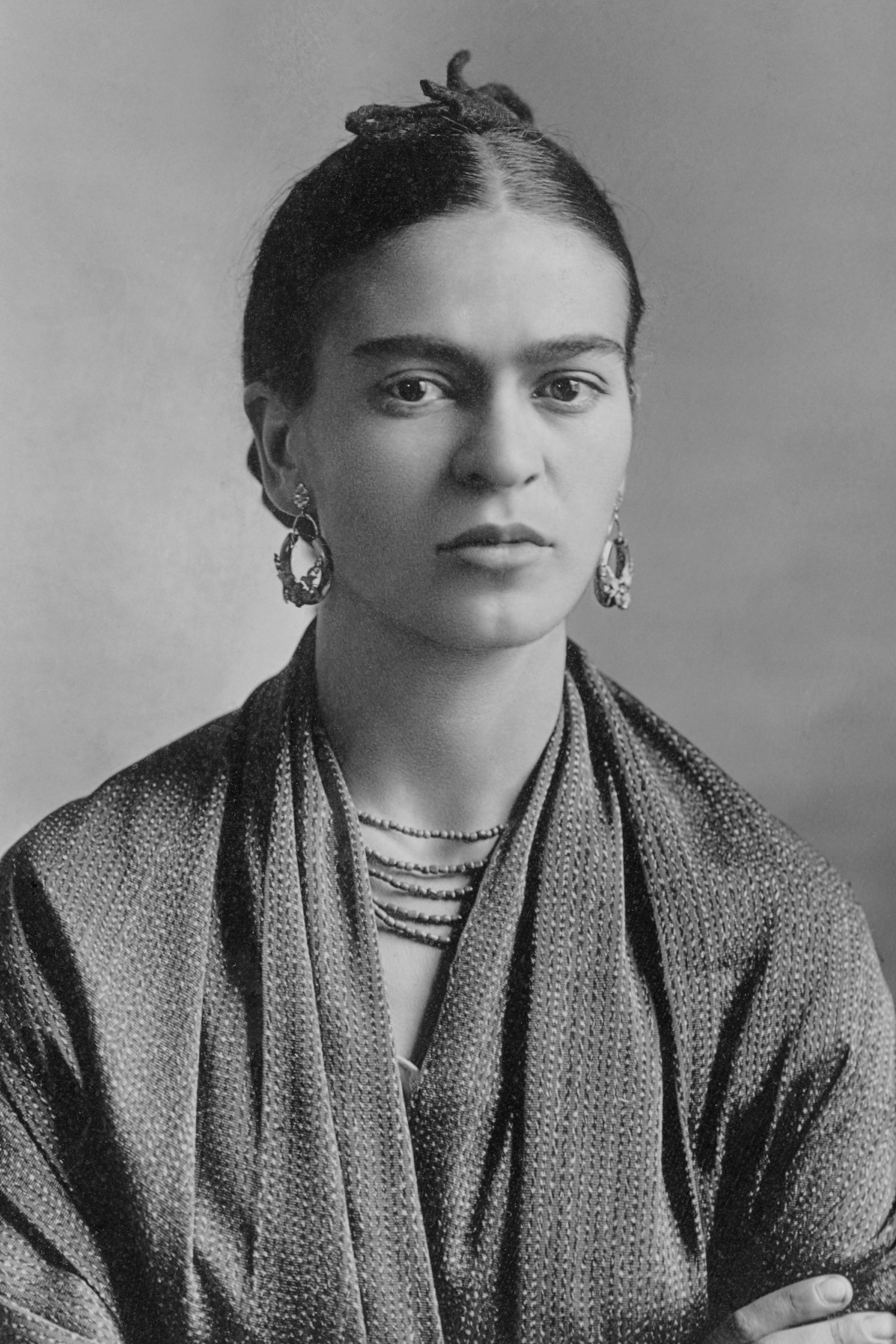

An undeniable example of a Latina icon is Frida Kahlo. Her image and artistry are widely recognized in the United States and around the world. While she was an activist and artist throughout her life, her fame expanded greatly after her death, not unlike other iconic Latina figures like Evita, Selena, and Celia Cruz. Now, images of Frida and her self-portraits appear on “stationery, posters, jewelry, hair clips, autobiographies, cookbooks, biographical books, chronological art books, refrigerator magnets, painting kits, wall hangings, and wrapping paper, to mention a few of the items in bookstores and novelty stores throughout the U.S., Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Spain.”38 A photograph of Kahlo is shown in Figure 10.4.4.

Sidebar: Dora the Explorer

Dora the Explorer debuted with wild success on the Nickelodeon children’s television network on August 14, 2000. Dora, an animated seven-year-old Latina girl, is the main character in a bilingual cartoon. She has light brown skin, dark brown eyes, and a voice bounding with endless enthusiasm. She wears orange shorts, a pink t-shirt, and pink-and-white tennis shoes, and carries a talking backpack and a map that help guide her adventures.39 As published in the Chicago Tribune:

In its first year, ‘Dora the Explorer,’ averaged 1.1 million viewers ages 2 to 5 and 2 million total viewers, according to Nielsen Co. These days, ‘Dora’ delivers an average of 1.4 million viewers ages 2 to 5 and 2.9 million total viewers, beating out competitors ‘Curious George’ and ‘Sid the Science Kid’ on PBS and Disney's ‘Mickey Mouse Clubhouse.’ Over the years, the show has won a Peabody award for excellence, an NAACP Image award and Parents' Choice awards, among others, and has received 16 Daytime Emmy nominations,” and won 2 Emmy Awards, including Outstanding Children’s Animated Program.40

Nicole Guidotti-Hernández argues that elements of Afro-Latinidad were present in an episode called “Dora, La Música” that features parranda and comparsa.41 These originate from righteously indignant Afro-Latina/o/x communities practicing self-determination by expressing oneself creatively and with music. The comparsa has a contested history because it is a distinctly Afro-Cuban practice that reflects African cultural retention and resistance to colonization.42 Comparsa music also has an oppositional quality because the European-origin majority characterized it as a barbaric African form of cultural expression located in the past. By highlighting these aspects of Latinx culture, Dora brings in age appropriate lessons that encourage cultural appreciation and knowledge.

Telenovelas, Nationalism, Gender and Sexuality

Telenovelas, sometimes just called novelas, are the most popular form of Latin American primetime television and cultural productions that can influence social life, capitalism, identity, and communicate learning moments of contemporary social problems (e.g. sexism, homophobia, domestic violence, etc.). Their plots usually center on love stories and family life and can represent political conflict, corruption, and other moral dilemmas.43 To this day, telenovelas are the most viewed television format in Mexico and across Latin America; produced by networks like Televisa, Telemundo, and TV Azteca.44 They are typically broadcasted 5 days a week, an hour per show, and can typically run for a year or more.

Telenovelas have been used to target consumers with messages intended to curb or in some way alter behavior and attitudes.45 Many telenovelas are inspired by a design by Miguel Sabido, a Mexican Telenovela writer, director and producer. He created a novela named, Simplemente María, that aired between 1969-1971. This novela was a catalyst for social change and economic production. It was found that Simplemente María contributed to an increase in Singer sewing machines and rising awareness of the working conditions of domestic workers in Latin America. Such changes in mindset yielded real changes for maids, including better treatment by employers and, in some cases, more flexible work schedules that allowed them to pursue their education in the evenings.46 Novelas are powerful storytelling platforms. Through fictional narratives, “lessons” are communicated through microcosms encoded with prosocial and antisocial behavior (e.g. villainous, innocent, professional, etc.)

Scholars credit Sabido as a pioneer of entertainment-education (E-E), which is the process of purposefully designing and implementing a media message to both entertain and educate, in order to increase audience knowledge about an educational issue, create favorable attitudes, and change overt behavior.47 Novelas like María la del Barrio, La Rosa de Guadalupe and Rebelde (RBD); are only a few that resemble this design. Novelas create and resemble Latinindades in many ways. Brazilian novelas, like O Bem-Amado (The Beloved) in 1973 by Dias Gomes, represent politics and identify new social processes and forces that shaped socioeconomic and political life in Brazil during the 1970s, including urbanization, modernization, the ‘new’ middle class, and a more assertive press.48

Traditionally understood as feminine cultural productions, telenovelas now attract audiences of all genders, ages, sexuality and social classes. With expanding audiences, we have also seen increased representation of topics related to gender diversity and sexual orientation in novelas. In many novelas, gender identity and sexuality have been understood primarily in binaristic terms in which feminine/flamboyant behavior is prescribed to cis-women and gay men, while macho/masculine behavior and caricatures are exclusive to cis-heterosexual men and masculine gay or bi men in novelas. This leads to feminine and passive gay men being the most stigmatized character in novelas.49 Tate describes further in the following quotation:

These polarized and farcical gender performances manifest themselves in the limited characterizations of male characters as either macho men or locas (a derogatory term used to denote extremely effeminate, presumably homosexual men). Consequently, for almost the entirety of the past century, the available gender narratives did not admit the existence of masculine homosexuals, nor effeminate heterosexuals, and telenovelas were no exception to this rule.50

The concepts of stereotypes and controlling images can explain how media representations exert power and influence over individuals’ identities and perceptions of others. However, greater representation and authentic storytelling can break down the barriers and dismantle controlling images that create restrictions on identity.

Footnotes

34 Mary Beltrán. “Image Analysis and Televisual Latinos.” In Race and Media: Critical Approaches, edited by Lori Kido Lopez, 27. New York, NY: New York University Press, 2020.

35 Isabel Molina Guzmán and Angharad N. Valdivia. “Brain, Brow, and Booty: Latina Iconicity in U.S. Popular Culture.” The Communication Review 7, no. 2 (April 1, 2004): 205–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714420490448723.

36 Guzmán and Valdivia, “Brain, Brow, and Booty,” 209.

38 Guzmán and Valdivia, 210-211.

39 Nicole M Guidotti-Hernández, “Dora The Explorer, Constructing ‘LATINIDADES’ and The Politics of Global Citizenship,” Latino Studies 5, no. 2 (July 2007): 210, https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.lst.8600254.

40 Yvonne Villarreal, “‘Dora’ Turns 10,” Chicagotribune.Com, August 15, 2010, sec. Tribune Newspapers, https://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/ct-xpm-2010-08-15-sc-tv-0811-dora-explorer-20100815-story.html.

41 Guidotti-Hernández, “Dora The Explorer.”

43 Mauro Porto. “Telenovelas and Representations of National Identity in Brazil.” Media, Culture & Society 33, no. 1 (January 1, 2011): 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443710385500; Viviana Rojas. “The Gender of Latinidad : Latinas Speak About Hispanic Television.” Communication Review 7, no. 2 (June 2004): 125–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714420490448688; Julee Tate. “Laughing All the Way to Tolerance? Mexican Comedic Telenovelas as Vehicles for Lessons Against Homophobia.” The Latin Americanist 58, no. 3 (2014): 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/tla.12036.

44 Antonio C La Pastina, “The Centrality of Telenovelas in Latin America’s Everyday Life:,” Global Media Journal 2, no. 2 (2003): 16.

45 Tate, “Laughing All the Way to Tolerance?” 51.

46 Arvind Singhal, Rafael Obregon, and Everett M. Rogers, “Reconstructing the Story of Simplemente Maria, the Most Popular Telenovela in Latin America of All Time,” Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands) 54, no. 1 (1995): 2.

47 Singhal et al., “Reconstructing the Story of Simplemente Maria.”

48 Porto. “Telenovelas and Representations of National Identity in Brazil.”

49 Tate. “Laughing All the Way to Tolerance?”

50 Julee Tate, “Redefining Mexican Masculinity in Twenty-First Century Telenovelas,” Hispanic Research Journal 14, no. 6 (December 2013): 541, https://doi.org/10.1179/1468273713Z.00000000068.