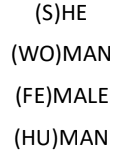

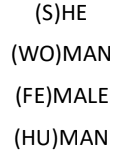

There has been extensive research on what is known for linguists as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Linguists and other social scientists,use this hypothesis to analyze the complex relations between language and culture. In short, Sapir-Whorf hypothesis explains that language shapes or influences the culture in which it is spoken.70 In other words, the languages we speak shape our social and cultural realities. So if we are speaking English, English (and all of the linguistic sexism found in it) would shape our cultural realities. Going by this hypothesis, one might argue labeling people as “female” or “male” shapes the idea of who the default individual would be. In that sense English can indeed be perceived as sexist, as it conveys intuitive notions that might shape the speaker’s and listener’s point of view. Take, for instance, the examples below:

In addition to language creating “defaults” in our standards for normalcy (and thereby creating deviations from those standards) we also create (or recreate) degradations of the female noun. For example, hound keeping its canine meaning, but bitch gaining another meaning entirely. Mistress and master used to be equal in meaning; now master evokes power, excellence, and ownership, whereas mistress is someone with whom you can cheat on your spouse. Incidentally, you cannot use master in the same way. Consider this old riddle that goes something like this: A father and son go out for a camping trip. On the way home from the camping trip the father and son get into a terrible car accident where the father is killed immediately upon impact. The son promptly gets rushed to the emergency room where the doctor inside prepares to save the boy’s life. Until, the doctor walks over to the critically injured boy and says, ‘I can’t operate on this boy. He’s my son.’ This is the end of the riddle. The question then becomes; who is the doctor? If you are like many people you’ll be puzzled at first thinking, “Uh, but you said the father died. How could he be in the emergency room if he is dead?” To which, of course, he cannot be (though, I’ve heard variations on the ghost dad / zombie dad theme numerous times!). That leaves only one option: the boy’s mother is the doctor. “Ahhhhhh, duh!” Yes, duh. But why was this obvious answer not immediately apparent? The answer has to do with the theme of this section: language has ways of seeing and understanding the world built into it that both reflect and reconstruct our social structures through our use of them. Since the word ‘doctor’ connotes a position of power, it is often understood to be held by a man. Though we now know full well women can and are doctors, the cultural and linguistic vestige from the past, the legacy of the power in Western culture, predisposes us to thinking the doctor must be a man, blinding us from the obvious fact that most people have two parents (and often a mother and a father)!

So who do we blame? English, right? Grab the pitchforks! Not quite. We cannot blame language; linguistic sexism is abstract and draws on human experiences to give it shape and meaning. And yet there is something in our heads that associates feminine with ‘pretty’ and masculine with ‘strong’. While language isn’t to blame, language does reflect and reinforce the culture of its users. Us!

Is language sexist? Only as much as the user is. Is sexism linguistic? Not only linguistic, but yes, the evidence in grammar is enough to draw conclusions pointing to sexism. How can we fight linguistic sexism and sexist language? Language is a reflection of us and does not exist without us, and our realities are shaped by language. So it’s almost like looking in a mirror and becoming frustrated when the image won’t change without us changing it. We would have to reconstruct sexism in thought before we could eliminate sexism in speech. Then, eliminating it in speech would reinforce eliminating it in thought. (However, going back to the examples provide earlier on using inclusive language can help the process of reconstruction our thoughts on sexism and gender standards.)

70 Deutscher, G. (2011). Through the language glass. Why the world looks different in other languages, Arrow Books,

London