8.3: Reasons for Attraction

- Page ID

- 167207

Researchers in various fields have studied attraction. Findings suggest that many reasons account for our attraction to others, including physical attractiveness, affect, proximity, perceived gain, similarities and differences, and disclosure. We will discuss some of these findings with the caveat that, as mentioned above, there is always more to know.

Physical Attractiveness

Although it may seem shallow to admit it, and while it is certainly not the only determinant of liking, people are strongly influenced, at least in initial encounters, by the physical attractiveness of their partners (Swami, Greven, & Furnham, 2007). In day-to-day interactions, it has been shown that people are more likely to pay attention to someone they find attractive. Perhaps this finding doesn’t surprise you too much, given the prevalence of physically attractive people in the media we consume. Movies and TV shows often feature unusually attractive people and we know that media shapes so much of how we understand the world around us. TV ads use attractive people to promote their products, and many people spend considerable amounts of money each year to make themselves look more attractive. (Langlois, Ritter, Roggman, & Vaughn, 1991).

While it is sometimes said that “beauty is in the eyes of the beholder,” this may not be completely true. In studies like Ramsey, J, et al’s 2004, Origins of a stereotype: categorization of facial attractiveness by 6‐month‐old infants, that expose participants of all ages to different facial images, there tends to be certain features that the participants found more pleasing to them. (Ramsey, Langlois, Hoss, Rubenstein, & Griffin, 2004). This preference is in part due to shared norms within cultures about what is attractive, which varies among cultures.

Leslie Zebrowitz and her colleagues have extensively studied the tendency for humans to prefer facial features that have youthful characteristics (Zebrowitz, 1996). These features include large, round, and widely spaced eyes, a small nose and chin, prominent cheekbones, and a large forehead. Zebrowitz has found that individuals who have youthful-looking faces are more liked, are judged as warmer and more honest, and also receive other positive outcomes. We may like baby-faced people because they remind us of babies. Because we respond to baby-faced people positively, they may respond to our positivity in turn, and act more positively to us.

Some faces are more symmetrical than others. People studied preferred faces that are more symmetrical when compared to those that were less symmetrical. This may be in part because of the perception that people with symmetrical faces are more healthy, and thus make better reproductive mates (Rhodes, 2006). Another hypothesis is that symmetrical faces seem more familiar and thus less threatening to us (Winkielman & Cacioppo, 2001). The attraction to symmetry is not limited to facial features. In Human Sexual Selection and Developmental Stability Gangestad & Thornhill, 1997, posit that body symmetry, meaning a correspondence of body parts in size and shape may trigger in someone the perception that that person will reproduce well. So we may be drawn to symmetrical body types for that reason whether we are aware of this or not (Gangestad & Thornhill, 1997).

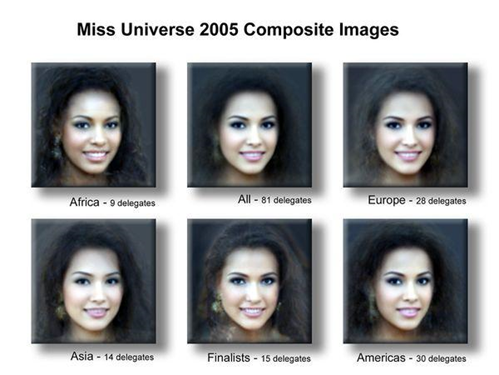

One might think that people prefer faces that are unusual or unique, but in fact the opposite is true (Langlois, Roggman, & Musselman, 1994). Langlois and Roggman (1990) showed college students the faces of men and women. The faces were composites made up of the average of 2, 4, 8, 16, or 32 faces. The researchers found that the more faces that were averaged into the image, the more attractive it was judged to be. As with the findings for facial symmetry, one possible explanation for our preference toward average faces is because they are more similar to the ones that we have frequently seen, and thus are more familiar to us (Grammer, Fink, Juette, Ronzal, & Thornhill, 2002).

Romantic chemistry is all about warm, gooey feelings that gush from the deepest depths of the heart...right? Not quite. Actually, the real boss behind attraction is your brain, which runs through a very quick, very complex series of calculations when assessing a potential partner. Dawn Maslar explores how our five senses contribute to this mating game, citing some pretty wild studies along the way. Watch Dawn Maslar: The science of attraction | TED Talk

[Directed by TOGETHER, narrated by Addison Anderson].

Symmetry may have evolutionary significance—people with these characteristics probably appear to be healthy and would make good reproductive partners. Although the preferences for youth, symmetry, and averageness appear to be universal, at least some differences in perceived attractiveness are due to social factors. What is seen as attractive in one culture may not be seen as attractive in another, and what is attractive in a culture at one time may not be attractive at another time. Additionally, these preferences are perhaps what leads to initial attraction in some cases but there are many other factors beyond physical appearance that cause people to find someone attractive.

Watch a visually dynamic attempt to recreate this evolution, Women's Ideal Body Types Throughout History showcased a diverse cast of models to depict more than 3,000 years of women’s ideal body types by each society’s standard of beauty.

Gender Differences in Perceived Attractiveness

You might wonder if gender influences what we find attractive. The answer is yes, although as in most cases with gender differences, the differences are outweighed by overall similarities. Overall, most people value physical attractiveness, as well as certain personality characteristics, such as kindness, humor, dependability, intelligence, and sociability and this is true across different genders and cultures (Li, Bailey, Kenrick, & Linsenmeier, 2002). For people who identify as heterosexual men, the physical attractiveness of a mate is most important whereas people who identify as heterosexual women do value attractiveness in a mate, but are more interested in the social status of a potential partner. (Li, Bailey, Kenrick, & Linsenmeier, 2002).

Some Data on Attraction Preferences Among Lesbians and Gay Men

Many of the same factors that influence sexual attraction for heterosexual people also apply to lesbians and gays. Research by Bailey et al. found that homosexual men showed similar preferences for physical attractiveness as heterosexual men, whereas homosexual women were similar to heterosexual women in ranking attractiveness relatively low ( Bailey, Gaulin, Agyei, & Gladue, 1994). Studies on the topic of age preferences suggest that in homosexual individuals are also similar to those of heterosexual individuals. Like their heterosexual counterparts, homosexual men show a tendency to be sexually interested in young men, and homosexual women show a tendency to be interested in women in their own age range (Kenrick, Keefee, Bryan, Barr, & Brown, 1995). The modularity hypothesis (Symons, 1979) explains homosexuality as different from heterosexuality only with respect to the sex of the desired partner, and suggests that homosexual and heterosexual individuals show similar patterns regarding other aspects of sexual psychology. Thus, no differences in age preferences would be expected based on sexual orientation alone. Less research is available about age preferences in bisexuals. A study by Adam (2000) suggests, however, that both homosexual men and bisexual men display the same interest in young partners as heterosexual men do.

Growing up, I specifically remember being sexually attracted to men and women, but I was unable to feel emotionally attracted to men until I was 20 years old. Despite being attracted to them, I was unable to feel love towards men, whereas I was able to feel love towards women. To this day, I am unsure as to why I was unable to feel emotional connections to men, but I’m sure a psychologist would blame my father! If I had to guess, I believe that sexual attraction differs from emotional attraction, and until I was 20 years old, I was unable to allow myself to be vulnerable around men.

Online dating apps have helped me express my sexuality and show vulnerability towards men, but it has also negatively impacted the ways that I perceive love due to the anonymity of the app. Due to this, I’ve begun to take more precautions before meeting up with anonymous people on the internet because I’ve noticed an unhealthy pattern of love bombing, or attempting to influence another person with an abundance of affection, in my intimate interactions with other men. Not only have I noticed myself quickly falling in love with Internet strangers, but I’ve noticed other people doing it as well!

In my early twenties, I worked in Arizona for a short period of time, and when I drove home, I spent the night in New Mexico, where I slept with a man I met on Grindr. The next day, I left New Mexico and drove to Minnesota, but I ended up returning to New Mexico after a week, with the intention of moving in with the man who I fell in love with way too quickly. The man and I dated for about a week before he cheated on me. After I found out the man cheated on me, I left New Mexico and vowed to never move across the country to begin a romantic relationship with someone unless I’ve spent more than 24 hours with the person! I’ve learned a lot about attraction and love throughout the last few years of my adulthood, and I’ve also experienced the consequences of wearing my heart on my sleeve!

Physical Proximity

When you ask some people how they met their significant other, you will often hear proximity is a factor in how they met. Perhaps, they were taking the same class, or their families went to the same grocery store. These common places create opportunities for others to meet and mingle. We are more likely to talk to people that we see frequently. Proximity allows people the opportunity to get to know one other and discover their similarities—all of which can result in a friendship or intimate relationship. Proximity is not just about geographic distance, but rather functional distance, or the frequency with which we cross paths with others. How does the notion of proximity apply in terms of online relationships? Deb Levine (2000) argues that in terms of developing online relationships and attraction, functional distance refers to being at the same place at the same time in a virtual world (i.e., a chat room or Internet forum)—crossing virtual paths.

Familiarity

One of the reasons why proximity matters to attraction is that it breeds familiarity; people are more attracted to that which is familiar. Just being around someone or being repeatedly exposed to them increases the likelihood that we will be attracted to them. We also tend to feel safe with familiar people, as it is likely we know what to expect from them. In 1968, Dr. Robert Zajonc labeled this phenomenon the mere-exposure effect. More specifically, he argued that the more often we are exposed to a stimulus (e.g., sound, person) the more likely we are to view that stimulus positively. In 1992, Moreland and Beach demonstrated this by exposing a college class to four women (similar in appearance and age) who attended different numbers of classes, finding that the more classes a woman attended, the more familiar, similar, and attractive they were considered by the other students.

There is a certain comfort in knowing what to expect from others; consequently, research suggests that we like what is familiar. While this is often on a subconscious level, research has found this to be one of the most basic principles of attraction (Zajonc, 1980). We are attracted to familiar people because we consider them to be safe and unlikely to cause harm. This doesn’t just apply to people we’ve actually seen before or to people who look familiar, but also to people who behave in ways that are familiar to us. For example, if you grew up with an alcoholic person, you may tend to be attracted to people who are alcoholics, because you find their behavior familiar. Even when someone’s behavior or personality is hurtful, on a subconscious level, some part of you may find comfort in the familiarity of that behavior. Good or bad, the environment in which you grew up is the only home you have ever known. This is one reason that it may be difficult for people to leave hurtful relationships, if that is what they are used to.

Similarities and Differences

It feels comforting when someone who appears to like the same things you like also has other similarities to you. Thus, you don’t have to explain yourself or give reasons for doing things a certain way. People with similar cultural, ethnic, or religious backgrounds are typically drawn to each other for this reason. This is also defined as a similarity thesis. The similarity thesis basically states that we are attracted to and tend to form relationships with others who are similar to us. There are three reasons why similarity thesis works: validation, predictability, and affiliation. First, it is validating to know that someone likes the same things that we do. It confirms and endorses what we believe. In turn, it increases support and affection. Second, when we are similar to another person, we can make predictions about what they will like and not like. We can make better estimations and expectations about what the person will do, and how they will behave. The third reason is due to the fact that we like others who are similar to us, and they may also like us because we are the same. Hence, it creates affiliation or connection with that other person.

However, there are some people who are attracted to someone completely opposite from who they are. This is where differences come into play. Differences can make a relationship stronger, especially when you have a relationship that is complementary. In complementary relationships, each person in the relationship can help satisfy the other person’s needs. For instance, one person likes to talk, and the other person likes to listen. They get along great because they can be comfortable in their communication behaviors and roles. In addition, they don’t have to argue over who will need to talk. One person may like to cook, and the other person likes to eat. Both people are getting things they like, and each other’s talents are complementary. Usually, friction will occur when there are differences of opinion or control issues. For example, if you have someone who loves to spend money and another person who loves to save money, it might be difficult to decide how to handle financial issues.

Perceived Gain

This type of relationship might appear similar to an economic model, and can be explained by exchange theory. In other words, we will form relationships with people who can offer us rewards that outweigh the costs. Rewards are benefits we want to acquire. They could be tangible (e.g., food, money, clothes) or intangible (support, admiration, status). Costs are undesirable tasks that we don’t want to expend a lot of energy to do. For instance, we don’t want to have to constantly nag the other person to call us, or spend a lot of time arguing about past items. Ideally a relationship will have fewer costs and more rewards. Often, when people are deciding whether or not to end a relationship, they will consider the costs and rewards.

Disclosure

Sometimes, we form relationships with others after we have disclosed something personal about ourselves. Disclosure increases liking, because it creates support and trust between people. We typically don’t disclose our most intimate thoughts to a stranger. We do this with people we are close to because it creates a bond with them. Disclosure does not automatically lead to forming a relationship. Disclosure needs to be appropriate and reciprocal. In other words, if you provide information, it must be mutual. If you reveal too much or too little, it might be regarded as inappropriate and can create tension. Also, if you disclose information too early in the relationship, it can be problematic.

Physiological Arousal

If you meet a new person when already physiologically aroused, this may increase the likelihood of developing an attraction. The likely mechanism is a misattribution of physiological arousal. For this to happen, the true source of the arousal must be ambiguous and not clear to the person what is responsible for it. The ambiguity may lead for a person to incorrectly label the true source of arousal (fear of heights, exercise to bring the heart rate up, etc.). According to this body of research, dinner and a movie are not the best first date activities. Instead, skydiving is the way to go!