8.4: Love Styles

- Page ID

- 167208

Attitudes toward love and perceptions of love may change throughout an individual’s life. College students may perceive love very differently from their parents or guardians. College students are in a different stage of life and their decisions reflect this. College students are living among people their age who are more than likely single or unmarried. There are more prospects for dating, and experimentation. College students are at the time in their life when committed relationships and the work involved may not be their best option. Instead they may choose “hooking up”. In contrast, individuals with children who are financially tied may view romantic relationships as partnerships, in which goal achievement (pay off the house, send kids to college, pay off debt, etc.) is as important as romance. We can trace these differences in perception of love as far back as the classical age. The Greeks distinguished four concepts of love:

- Storge: loving attachment and non-sexual affection; the type that binds parents and children

- Agape: selfless love similar to generosity and charity

- Philia: friendship love, liking and respect rather than sexual desire

- Eros: passionate love similar to modern concept of passion

What concept of love is depicted on an image of the ancient Greek drinking cup?

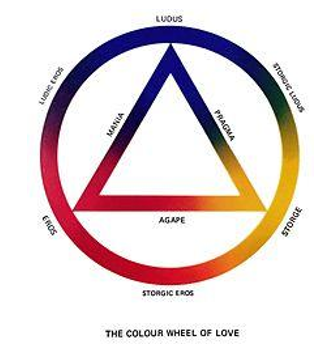

Color Wheel Theory of Love

The color wheel theory of love was conceptualized by Canadian psychologist John Alan Lee in 1973. Lee describes six love styles, using several Latin and Greek words for love. First introduced in his book, Colours of Love: An Exploration of the Ways of Loving (1973), Lee defines three primary, three secondary, and nine tertiary love styles, describing them in the traditional color wheel. The three primary types are Eros, Ludus and Storge, and the three secondary types are Mania, Pragma and Agape.

Eros is the Greek term for romantic, passionate, or sexual love, from which the term "erotic" is derived. Lee describes Eros as a passionate physical and emotional love feeling of wanting to satisfy, create sexual contentment, security, and aesthetic enjoyment for each other, it also includes creating sexual security for the other by striving to forsake options of sharing one's intimate and sexual self with outsiders. It is a highly sensual, intense, passionate style of love. Erotic lovers choose their lovers by intuition or "chemistry". They are more likely to say they fell in love at first sight than those of other love styles.

Storge is the Greek term for familial love. Lee defines Storge as growing slowly out of friendship and based more on similar interests and a commitment to one another rather than on passion. However, he chooses Storge, rather than the term Philia (the usual term for friendship) to describe this kind of love.

Ludic means "game" or "school" in Latin. Lee uses the term to describe those who see love as a desire to want to have fun with each other, to do activities indoor and outdoor, tease, indulge, and play harmless pranks on each other. The acquisition of love and attention itself may be part of the game. Individuals with this love style have a low tolerance for commitment, jealousy, and strong emotional attachment.

In contrast, agape love involves altruism, giving, and other-centered love. This love style approaches relationships in a non-demanding style with gentle caring and tolerance for others. Lee describes agape as an altruistic love, given by the lover who sees it as his obligation without expecting reciprocity. According to Lee, Agapic lovers are usually older and more emotionally mature, thus a love guided by will and reason rather than emotion or attraction.

Pragma love is known as practical love involving logic and reason. Arranged marriages were often arranged for functional purposes. Kings and Queens of different countries often married to form alliances. This love style may seek out a romantic partner for financial stability, ability to parent, or simple companionship.

Mania is the final love style characterized by dependence, uncertainty, jealousy, and emotional upheaval. This type of love is insecure and needs constant reassurance.

These love styles are not mutually independent. An individual may approach love from a pragmatic stance and have found love that provides financial stability. However, they still feel insecure (representative of mania) about whether their romantic partner will remain with them, thus ensuring continued financial stability. People engage in each of these love styles, and it is simply a matter of how much of each love style a person possesses.

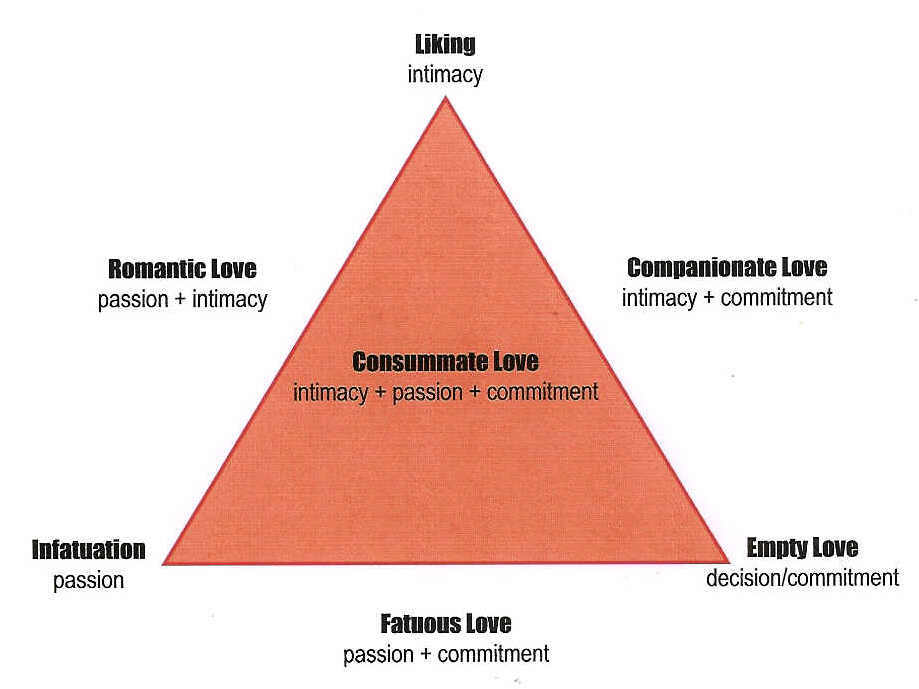

Sternberg's Triangular Theory of Love

Is all love the same or are there different types of love? Examining these questions more closely, Robert Sternberg’s (2004, 2007) work has focused on the notion that all types of love are comprised of three distinct areas: intimacy, passion, and commitment. Intimacy includes caring, closeness, and emotional support. The passion component of love is comprised of physiological and emotional arousal; these can include physical attraction, emotional responses that promote physiological changes, and sexual arousal. Lastly, commitment refers to the cognitive process and decision to commit to love another person and the willingness to work to keep that love over the course of your life. The elements involved in intimacy (caring, closeness, and emotional support) are generally found in all types of close relationships—for example, a mother’s love for a child or the love that friends share. Interestingly, this is not true for passion. Passion is unique to romantic love, differentiating friends from lovers. In sum, depending on the type of love and the stage of the relationship (i.e., newly in love), different combinations of these elements are present.

- Liking in this case is not used in a trivial sense. Sternberg says that this intimate liking characterizes true friendships, in which a person feels a bondedness, a warmth, and a closeness with another but not intense passion or long-term commitment.

- Infatuated love is often what is felt as "love at first sight." But without the intimacy and the commitment components of love, infatuated love may disappear suddenly.

- Empty love: Sometimes, a stronger love deteriorates into empty love, in which the commitment remains, but the intimacy and passion have died. In cultures in which arranged marriages are common, relationships often begin as empty love.

- Romantic love: Romantic lovers are bonded emotionally (as in liking) and physically through passionate arousal.

- Companionate love is often found in marriages in which the passion has gone out of the relationship, but a deep affection and commitment remain. Companionate love is generally a personal relation you build with somebody you share your life with, but with no sexual or physical desire. It is stronger than friendship because of the extra element of commitment.

- Fatuous love can be exemplified by a whirlwind courtship and marriage in which a commitment is motivated largely by passion, without the stabilizing influence of intimacy.

- Consummate love is the complete form of love, representing the ideal relationship toward which many people strive but which apparently few achieve. Sternberg cautions that maintaining a consummate love may be even harder than achieving it. He stresses the importance of translating the components of love into action. "Without expression," he warns, "even the greatest of loves can die" (Sternberg 1988, p.341). Consummate love may not be permanent. For example, if passion is lost over time, it may change into companionate love.

The balance among Sternberg’s three aspects of love is likely to shift through the course of a relationship. A strong dose of all three components-found in consummate love-typifies, for many of us, an ideal relationship. However, time alone does not cause intimacy, passion, and commitment to occur and grow. Knowing about these components of love may help couples avoid pitfalls in their relationship, work on the areas that need improvement, or help them recognize when it might be time for a relationship to come to an end.

Taking this the study of love a step further, Anthropologist Helen Fisher studied fMRI brain scans of people who had just fallen in love and observed that their brain chemistry was “going crazy,” similar to the brain of an addict on a drug high (Cohen, 2007). Specifically, serotonin production increased by as much as 40% in newly in-love individuals. Further, those newly in love tended to show obsessive-compulsive tendencies. Conversely, when a person experiences a breakup, the brain processes it in a similar way to quitting a heroin habit (Fisher, Brown, Aron, Strong, & Mashek, 2009). Thus, those who believe that breakups are physically painful are correct! Another interesting finding is that long-term love and sexual desire activate different areas of the brain. Sexual needs activate the part of the brain that is particularly sensitive to innately pleasurable things such as food, sex, and drugs (i.e., the striatum—a rather simplistic reward system), whereas love requires conditioning—it is more like a habit. When sexual needs are rewarded consistently, then love can develop. In other words, love grows out of positive rewards, expectancies, and habit (Cacioppo, Bianchi-Demicheli, Hatfield & Rapson, 2012).

Dr. Helen Fisher, senior research fellow at the Kinsey Institute, discusses how intense romantic love affects our long-term goals here. They explain how to maintain novelty, the fuel of romantic love, and how to be aware of the brain regions that affect satisfaction in a relationship