1.11: Module 11- How Does Gender Play a Role in Aggression and Crime?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 188365

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Case Study: Incel

As mentioned in module one, there are a number of men’s groups. Some are supportive of women and women’s rights, while others disguise their support in thinly veiled benevolent sexism. Incel is neither; it is openly hostile toward women, especially feminists, and toward women and men who engage in sex. Incel means involuntary celibacy. Members blame feminism for their celibacy. They believe that women are genetically inferior to men, and resent that women seek genetically superior males (Scaptura & Boyle, 2020). In online communities, members routinely comment on their frustration and anger of not being able to attract women. If incel was little more than a self-pity stage to vent, people would not be as concerned as they are about this group. A number of incel members hold very radical views; views that endorse the sexual subjugation of women, and that violence against women, especially if they are feminists, is legitimate.

In May of 2014, Elliot Rodger, a self-proclaimed member of incel, killed 6 people and wounded 14 others. His posted manifesto revealed that he held many of these radical views toward women. He became an “incel hero” to tens of thousands of members (BBC, 2018). One member who saw Rodger as a hero drove his van into pedestrians in Toronto, Canada, killing 10 and injuring 15. In a Facebook post before the attack he referenced Rodger’s actions and the belief that “the incel revolution had begun” (Wendling, 2018). Six months later there was a shooting spree in a Florida yoga studio, killing 2 women and wounding several others. In online videos the shooter expressed his support of groups like incel, and blamed women’s lack of understanding of the societal pressures placed on men (Chavez & McLaughlin, 2018).

According to Hines (2019) in the last decade, seven mass shootings have been perpetrated by men with ties to incel. Mass shooters often have a history of gender-based violence (Scaptura & Boyle, 2020). Moreover, as mass shooters frequently target romantic partners and family members, women and children are disproportionately among the victims. Groups like incel offer insight into the alarming toxicity of traditional views of masculinity.

Human Aggression

Aggression is behavior that is intended to harm another individual. Aggression may occur in the heat of the moment, for instance, when a jealous lover strikes out in rage or the sports fans at a university light fires and destroy cars after an important basketball game. Or it may occur in a more cognitive, deliberate, and planned way, such as the aggression of a bully who steals another child’s toys, a terrorist who kills civilians to gain political exposure, or a hired assassin who kills for money.

Not all aggression is physical. Aggression also occurs in nonphysical ways, as when children exclude others from activities, call them names, or spread rumors about them. Paquette and Underwood (1999) found that both boys and girls rated nonphysical aggression, such as name- calling as making them feel more “sad and bad” than did physical aggression. Bullying can include physical, verbal, or even cyber-behaviors.

Aggression is Part of Human Nature:

We may aggress against others in part because it allows us to gain access to valuable resources such as food, territory, and desirable mates, or to protect ourselves from direct attack by others. If aggression helps in the survival of our genes, then the process of natural selection may well have caused humans, as it would any other animal, to be aggressive (Buss & Duntley, 2006).

There is evidence for the genetics of aggression. Aggression is controlled in large part by the amygdala. One of the primary functions of the amygdala is to help us learn to associate stimuli with the rewards and the punishment that they may provide. The amygdala is particularly activated in our responses to stimuli that we see as threatening and fear-arousing. When the amygdala is stimulated, in either humans or in animals, the organism becomes more aggressive.

However, just because we can aggress does not mean that we will aggress. It is not necessarily evolutionarily adaptive to aggress in all situations. Neither people nor animals are always aggressive; they rely on aggression only when they feel that they absolutely need to (Berkowitz, 1993a). The prefrontal cortex serves as a control center on aggression; when it is more highly activated, we are more able to control our aggressive impulses. Research has found that the cerebral cortex is less active in murderers and death row inmates, suggesting that violent crime may be caused by a failure or reduced ability to regulate aggression (Davidson et al., 2000).

Hormones are also important in regulating aggression. Most important in this regard is the male sex hormone testosterone, which is associated with increased aggression in both males and females. Research conducted on a variety of animals has found a positive correlation between levels of testosterone and aggression. This relationship seems to be weaker among humans than among animals, yet it is still significant (Dabbs et al., 1996).

Consuming alcohol increases the likelihood that people will respond aggressively to provocations, and even people who are not normally aggressive may react with aggression when they are intoxicated (Graham et al., 2006). Alcohol reduces the ability of people who have consumed it to inhibit their aggression because when people are intoxicated, they become more self-focused and less aware of the social constraints that normally prevent them from engaging aggressively (Bushman & Cooper, 1990; Steele & Southwick, 1985).

Negative Experiences Increase Aggression:

When asked about the times that you have been aggressive, you would probably state that many of them occurred when you were angry, in a bad mood, tired, in pain, sick, or frustrated. You would be right because we are much more likely to aggress when we are experiencing negative emotions. The following are some causes of aggression:

- One important determinant of aggression is frustration. When we are frustrated we may lash out at others, even at people who did not cause the frustration. In some cases, the aggression is displaced aggression, which is aggression that is directed at an object or person other than the person who caused the frustration (Marcus-Maxwell et al., 2000).

- Aggression is greater on hot days than it is on cooler days and during hot years than during cooler years, and most violent riots occur during the hottest days of the year (Bushman et al., 2005).

- Pain also increases aggression (Berkowitz, 1993b).

If we are aware that we are feeling negative emotions, we might think that we could release those emotions in a relatively harmless way, such as by punching a pillow or kicking something, with the hopes that doing so will release our aggressive tendencies. This is incorrect! Catharsis or the idea that observing or engaging in less harmful aggressive actions will reduce the tendency to aggress later in a more harmful way, was considered by many as a way of decreasing violence. However, as far as social psychologists have been able to determine, catharsis simply does not work. Rather than decreasing aggression, engaging in aggressive behaviors of any type increases the likelihood of later aggression.

Research indicates that males exhibit greater physical aggression, and this difference appears around the age of two (Hyde, 2014). Although this gender difference in aggression is routinely found, in research in which the context of the situation is changed to reflect greater deindividuation, or greater anonymity, gender differences disappear. This indicates that gender role expectations appear to play a part in how aggressive an individual behaves. The stereotype that females exhibit significantly more relational aggression,or verbal aggression that is intended to harm peer relationships, has also not been validated in research studies.

Bullying:

According to Stopbullying.gov (2016), a federal government website managed by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, bullying is defined as unwanted, aggressive behavior among school aged children that involves a real or perceived power imbalance. Further, the aggressive behavior happens more than once or has the potential to be repeated. There are different types of bullying, including verbal bullying, which is saying or writing mean things, teasing, name calling, taunting, threatening, or making inappropriate sexual comments. Social bullying, also referred to as relational bullying, involves spreading rumors, purposefully excluding someone from a group, or embarrassing someone on purpose. Physical Bullying involves hurting a person’s body or possessions.

According to Stopbullying.gov (2016), a federal government website managed by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, bullying is defined as unwanted, aggressive behavior among school aged children that involves a real or perceived power imbalance. Further, the aggressive behavior happens more than once or has the potential to be repeated. There are different types of bullying, including verbal bullying, which is saying or writing mean things, teasing, name calling, taunting, threatening, or making inappropriate sexual comments. Social bullying, also referred to as relational bullying, involves spreading rumors, purposefully excluding someone from a group, or embarrassing someone on purpose. Physical Bullying involves hurting a person’s body or possessions.

A more recent form of bullying is cyberbullying, which involves bullying using electronic technology. Examples of cyberbullying include sending mean text messages or emails, creating fake profiles, and posting embarrassing pictures, videos or rumors on social networking sites. Children who experience cyberbullying have a harder time getting away from the behavior because it can occur any time of day and without being in the presence of others. Additional concerns of cyberbullying include that messages and images can be posted anonymously, distributed quickly, and be difficult to trace or delete. Children who are cyberbullied are more likely to: experience in-person bullying, be unwilling to attend school, receive poor grades, use alcohol and drugs, skip school, have lower self-esteem, and have more health problems (Stopbullying.gov, 2016).

The National Center for Education Statistics and Bureau of Justice statistics indicate that in 2010-2011, 28% of students in grades 6-12 experienced bullying and 7% experienced cyberbullying. The 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, which monitors six types of health risk behaviors, indicate that 20% of students in grades 9-12 experienced bullying and 15% experienced cyberbullying (Stopbullying.gov, 2016).

Those at risk for bullying:

Bullying can happen to anyone, but some students are at an increased risk for being bullied including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered (LGBT) youth, those with disabilities, and those who are socially isolated. Additionally, those who are perceived as different, weak, less popular, overweight, or having low self-esteem, have a higher likelihood of being bullied.

Toxic Masculinity

Are traditional masculine norms harmful?

In 2018, the American Psychology Association (APA) provided guidelines to assist psychologists when working with men and boys (APA, 2018). The guidelines were developed over 13 years and were based on 40 years of research. A significant aspect of the guidelines was that traditional masculine norms, such as suppressing their emotions and not seeking help, undermined men’s and boy’s health. Additionally, stoicism, competitiveness, dominance and aggression were designated as harmful to males (Pappas, 2019). The guidelines further indicated that men are more likely to be victims of violence, suicide, homicide and substance use. The intent of the guidelines was to provide research and suggest ways that psychologists could assist men and boys (APA, 2019).

These guidelines were approved in August 2018 and were printed in the APA’s monthly journal for psychologists in January 2019. Because of the article, social media became aware of the guidelines, and many media outlets asserted that APA had “declared war on men” and was attempting to remake them (APA, 2019). The attack on the APA guidelines coincided with Gillette Razor’s ad campaign that addressed toxic masculinity behaviors, such as bullying and “boys will be boys” excuses for inappropriate behavior (Russo, 2019). Both the APA guidelines and the Gillette ad received praise and condemnation from viewers. The same behaviors were either seen as normal masculine gender roles or toxic male expressions. So, when does traditional male behaviors become toxic?

The term toxic masculinity was originally defined by Kupers (2005) while working with prison inmates. Kupers called toxic masculinity, “the constellation of socially regressive male traits that serve to foster domination, the devaluation of women, homophobia, and wanton violence” (p. 714). Kupers found that in prison, toxic masculinity is exaggerated and results in prison fights, assaults on guards, prison rapes, hypercompetitive interactions, and resistance to psychotherapy.

According to Parent et al. (2019) toxic masculinity is characterized by the enforcement of rigid gender roles, endorsement of misogynistic and homophobic attitudes, and involves the need to aggressively compete with and dominate others. Parent et al. researched whether there was a relationship between toxic masculinity and negative online interactions. Because many online environments are anonymous, the individuals’ pervasive need to dominate and control was hypothesized to promote negative engagement with online materials. Results indicated that “men who more strongly endorsed the dominance–heterosexism–misogyny triad of aspects of conformity to masculine norms were more likely to report negative online interactions,” (p. 282). These negative interactions included seeking out and reading content with which one disagreed and making hostile responses to such disagreement.

Mikorski and Szymanski (2017) reviewed the research on the relationships between certain aspects of traditional masculine ideology and sexual violence. They reported that men who scored higher on measures of hypersexuality, toughness, antifemininity, and male dominance were more likely to have committed domestic violence acts against their partners. They also indicated that males whose peer groups reflected toxic behaviors, such as demeaning their female partners, using sexual force against women, and being physically aggressive, were more likely to have engaged in sexual assaults themselves. In their own research, Mikorski and Szymanski also found that having abusive male peer groups and conforming to the masculine norms of power over women, violence, and exhibiting sexual promiscuity, predicted unwanted sexual advances toward women.

Mikorski and Szymanski (2017) reviewed the research on the relationships between certain aspects of traditional masculine ideology and sexual violence. They reported that men who scored higher on measures of hypersexuality, toughness, antifemininity, and male dominance were more likely to have committed domestic violence acts against their partners. They also indicated that males whose peer groups reflected toxic behaviors, such as demeaning their female partners, using sexual force against women, and being physically aggressive, were more likely to have engaged in sexual assaults themselves. In their own research, Mikorski and Szymanski also found that having abusive male peer groups and conforming to the masculine norms of power over women, violence, and exhibiting sexual promiscuity, predicted unwanted sexual advances toward women.

Rape

The United States Department of Justice (2012) defines rape as the penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part of object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim. This definition replaced the previous rape definition from 1927 because it was considered outdated and did not reflect the experiences of survivors. According to the Attorney General:

For the first time ever, the new definition includes any gender of victim and perpetrator, not just women being raped by men. It also recognizes that rape with an object can be as traumatic as penile/vaginal rape. This definition also includes instances in which the victim is unable to give consent because of temporary or permanent mental or physical incapacity. Furthermore, because many rapes are facilitated by drugs or alcohol, the new definition recognizes that a victim can be incapacitated and thus unable to consent because of ingestion of drugs or alcohol. Similarly, a victim may be legally incapable of consent because of age. Physical resistance is not required on the part of the victim to demonstrate lack of consent. (para 2)

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2020), the rate of rape and sexual assault victimization in 2019 was 1.7 persons per 1000. This rate was lower than in 2018 when it was 2.7 persons per 1000, and reflected an overall decrease in violent crimes from 2018 to 2019. However, getting accurate statistics on the occurrences of rape and sexual assaults are difficult to obtain as these crimes are under-reported, especially among men (Budd et al., 2017). Further, when looking at research that uses self-report measures, which usually indicate higher rates than official reports, the differences in measurement and definition of sexual assault make it difficult to know the true numbers (Fedina et al., 2016).

College and Sexual Assaults:

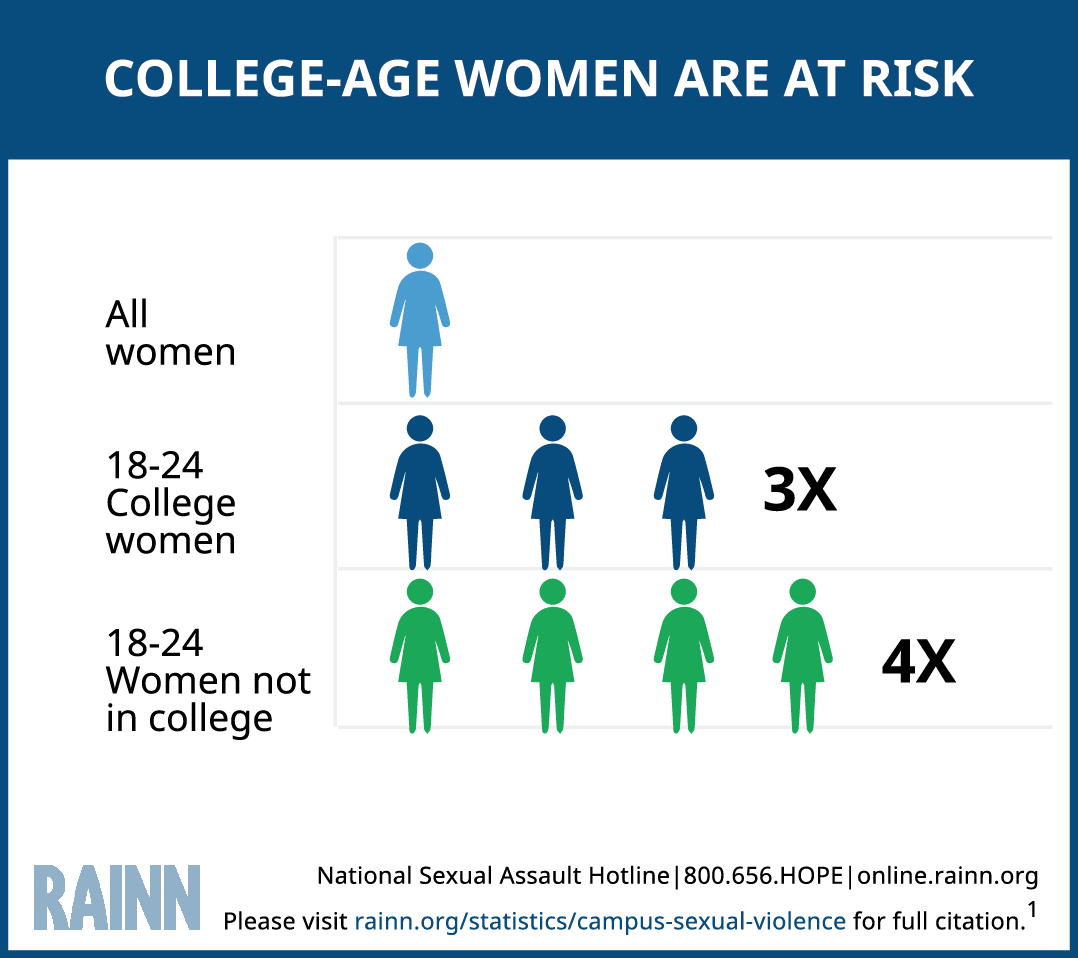

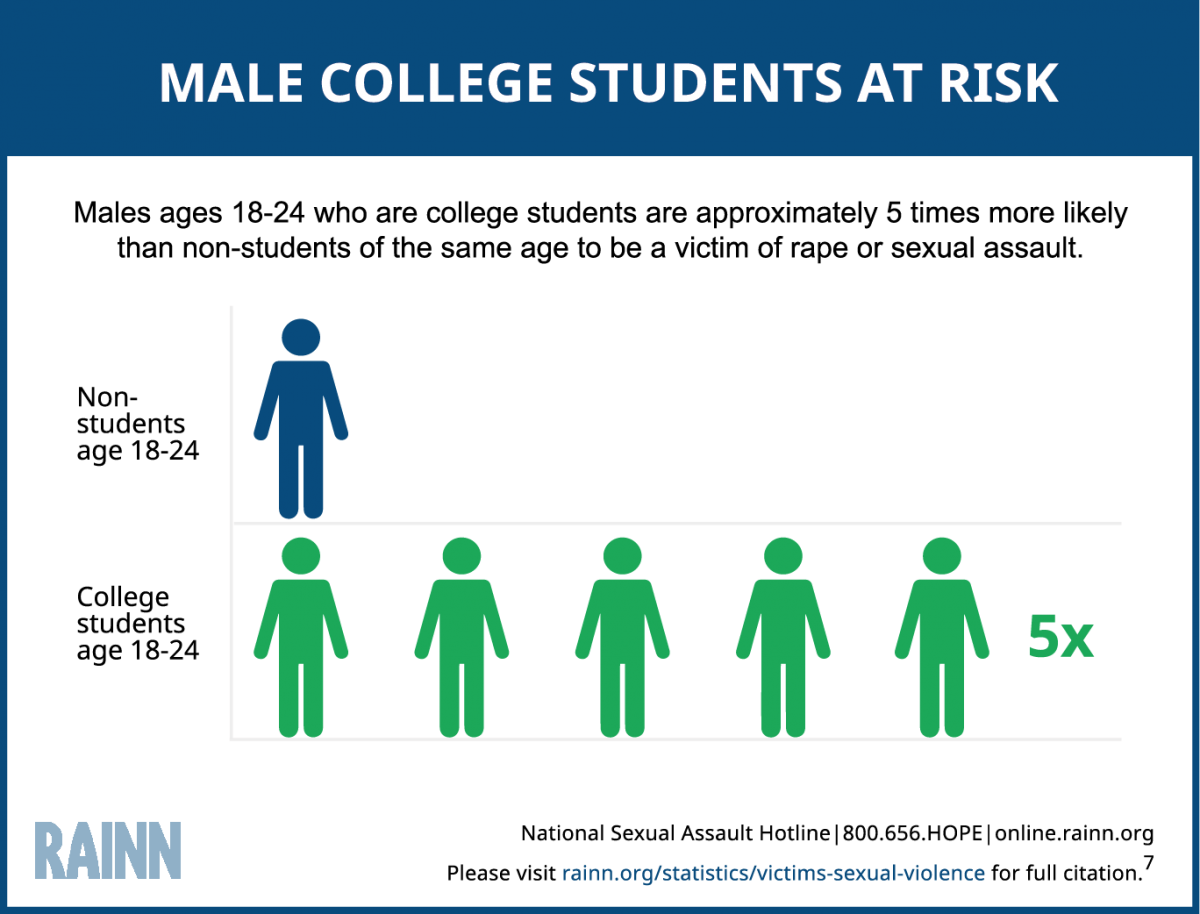

The majority of sexual assault victims are between the ages of 18 and 34, and being a college student is a greater risk factor for a males than it is for females (RAINN, 2020). Being an 18-24 year-old female and not in college, results in being four times more likely than the average female to be sexually assaulted. For those in college, they are three times more likely to be assaulted than the average female. For males, being in college makes them five times more likely to be sexually assaulted than their same-aged peers who are not in college. The differences for males may be due to an increased willingness to report sexual assaults in college due to exposure to campus sexual assault prevention programs (Streng & Kamimura, 2015).

T

T

Looking at college demographics and sexual assaults, Mellins et al. (2017) found that gender nonconforming students (38%) were assaulted more than women (28%) or men (12.5%). A non-heterosexual identity, difficulty paying for basic necessities, fraternity/sorority membership, participation in more casual sexual encounters versus exclusive/monogamous or no sexual relationships, binge drinking, and experiencing sexual assault before college were also factors associated with higher rates of sexual assault in college. Budd et al. (2017) found that the average age for male and female victims was approximately 19 years old, but perpetrators who assaulted females tended to be an average of 23 years old, while those assaulting males were 29. Additionally, college sexual assaults with male victims were more likely to include multiple offenders, but less likely to involve a stranger or result in injuries in comparison to sexual assaults with female victims.

Intimate Partner Abuse

Violence in romantic relationships is a significant concern for women in early adulthood as females aged 18 to 34 generally experience the highest rates of intimate partner violence. According to the most recent Violence Policy Center (2018) study, more than 1,800 women were murdered by men in 2016. The study found that nationwide, 93% of women killed by men were murdered by someone they knew, and guns were the most common weapon used. The national rate of women murdered by men in single victim/single offender incidents dropped 24%, from 1.57 per 100,000 in 1996 to 1.20 per 100,000 in 2016. However, since reaching a low of 1.08 per 100,000 women in 2014, the 2016 rate increased 11%.

Intimate partner violence is often divided into situational couple violence, which is the violence that results when heated conflict escalates, and intimate terrorism, in which one partner consistently uses fear and violence to dominate the other (Bosson, et al., 2019). Men and women equally use and experience situational couple violence, while men are more likely to use intimate terrorism than are women. Consistent with this, a national survey described below, found that female victims of intimate partner violence experience different patterns of violence, such as rape, severe physical violence, and stalking than male victims, who most often experienced more slapping, shoving, and pushing.

The last National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) was conducted in 2015 (Smith et al., 2018). The NISVS examines the prevalence of intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and stalking among women and men in the United States over the respondent’s lifetime and during the 12 months before the interview. A total of 5,758 women and 4,323 men completed the survey. Based on the results, women are disproportionately affected by intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and stalking. Results included:

- Nearly 1 in 3 women and 1 in 6 men experienced some form of contact sexual violence during their lifetime.

- Nearly 1 in 5 women and 1 in 39 men have been raped in their lifetime.

- Approximately 1 in 6 women and 1 in 10 men experienced sexual coercion (e.g., sexual pressure from someone in authority, or being worn down by requests for sex).

- Almost 1 in 5 women have been the victim of severe physical violence by an intimate partner, while 1 in 7 men have experienced the same.

- 1 in 6 women have been stalked during their lifetime, compared to 1 in 19 men.

- More than 1 in 4 women and more than 1 in 10 men have experienced contact sexual violence, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner and reported significant short- or long-term impacts, such as post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and injury.

- An estimated 1 in 3 women experienced at least one act of psychological aggression by an intimate partner during their lifetime.

- Men and women who experienced these forms of violence were more likely to report frequent headaches, chronic pain, difficulty with sleeping, activity limitations, poor physical health, and poor mental health than men and women who did not experience these forms of violence.

Child and Adolescent Abuse and Neglect

The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), 2019) defines child abuse and neglect as: Any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation; or an act or failure to act, which presents an imminent risk of serious harm (p. viii). Each state has its own definition of child abuse based on the federal law, and most states recognize five major types of maltreatment: neglect, physical abuse, psychological maltreatment, sexual abuse and sex trafficking. Each of the forms of child maltreatment may be identified alone, but they can occur in combination.

The most recent national child abuse data is from 2018, and these statistics were collected using the annual Child Maltreatment Report Series (HSS, 2020). States provide the data for this report through the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System. The national number of children who received a child protective services investigation increased 8.4% from 2014 (3,261,000) to 2018 (3,534,000). Of those investigated, approximately 678,000 children were found to be victims of child abuse and neglect. This equates to a national rate of 9.2 victims per 1,000 children in the population. Of those, 48.5% were boys, 51.2% were girls, and the gender of 0.3% children was unknown. This results in a rate of 9.6 girls per 1000 and 8.7 boys per 1000.

The majority of victims (84.5%) suffered from a single maltreatment type (HSS, 2020). Three-fifths (60.8%) of victims were neglected only, 10.7 percent were physically abused only, 7.0 percent were sexually abused only, 0.1% were victims of sex trafficking, and 15.5% experienced multiple types of abuse. Although less in overall number of cases, boys have a higher child fatality rate than girls; 2.87 per 100,000 boys, compared with 2.19 per 100,000 girls in the population. For most of the categories, there were no sex differences, however for sex trafficking, the majority (89.1%) were female, while only 10.4% were male. The largest percentages for victims of sex trafficking (71.9%) are in the age group 14–17, and this is true for both sexes. Sex trafficking will be further discussed as a form of human trafficking.

More than one-half (53.8%) of perpetrators of child abuse are female and 45.3% of perpetrators are male; 0.9 percent are of unknown sex (HSS, 2020). The majority (77.5%) of perpetrators are a parent of their victim, 6.4 percent of perpetrators are a relative other than a parent, and 4.2 percent had a multiple relationship to their victims. Approximately 4.0% of perpetrators have an “other” relationship to their victims, including parent’s partner, babysitters, friends, neighbors, foster sibling, etc.

Sexual Abuse:

Sexual abuse is defined as a type of maltreatment that refers to the involvement of the child in sexual activity to provide sexual gratification or financial benefit to the perpetrator, including contacts for sexual purposes, molestation, statutory rape, prostitution, pornography, expo-sure, incest, or other sexually exploitative activities (HSS, 2020). Sexual abuse statistics reflect a greater percentage of girls, as approximately 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys experience child sexual abuse at some point in childhood (CDC, 2020). The median age for sexual abuse is 8 or 9 years for both boys and girls (Finkelhorn et al., 1990). Unfortunately, many children wait to report or never report child sexual abuse, so these numbers are probably a low estimate.

Sexual abuse is defined as a type of maltreatment that refers to the involvement of the child in sexual activity to provide sexual gratification or financial benefit to the perpetrator, including contacts for sexual purposes, molestation, statutory rape, prostitution, pornography, expo-sure, incest, or other sexually exploitative activities (HSS, 2020). Sexual abuse statistics reflect a greater percentage of girls, as approximately 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys experience child sexual abuse at some point in childhood (CDC, 2020). The median age for sexual abuse is 8 or 9 years for both boys and girls (Finkelhorn et al., 1990). Unfortunately, many children wait to report or never report child sexual abuse, so these numbers are probably a low estimate.

Most boys and girls are sexually abused by a male. Although rates of sexual abuse are higher for girls than for boys, boys may be less likely to report abuse because of the cultural expectation that boys should be able to take care of themselves and because of the stigma attached to homosexual encounters (Finkelhorn et al., 1990). Girls are more likely to be abused by family member and boys by strangers. According to Valente (2005) sexual abuse can create feelings of self-blame, betrayal, shame and guilt. Further, sexual abuse is particularly damaging when the perpetrator is someone the child trusts and may lead to depression, anxiety, problems with intimacy, and suicide.

ACES:

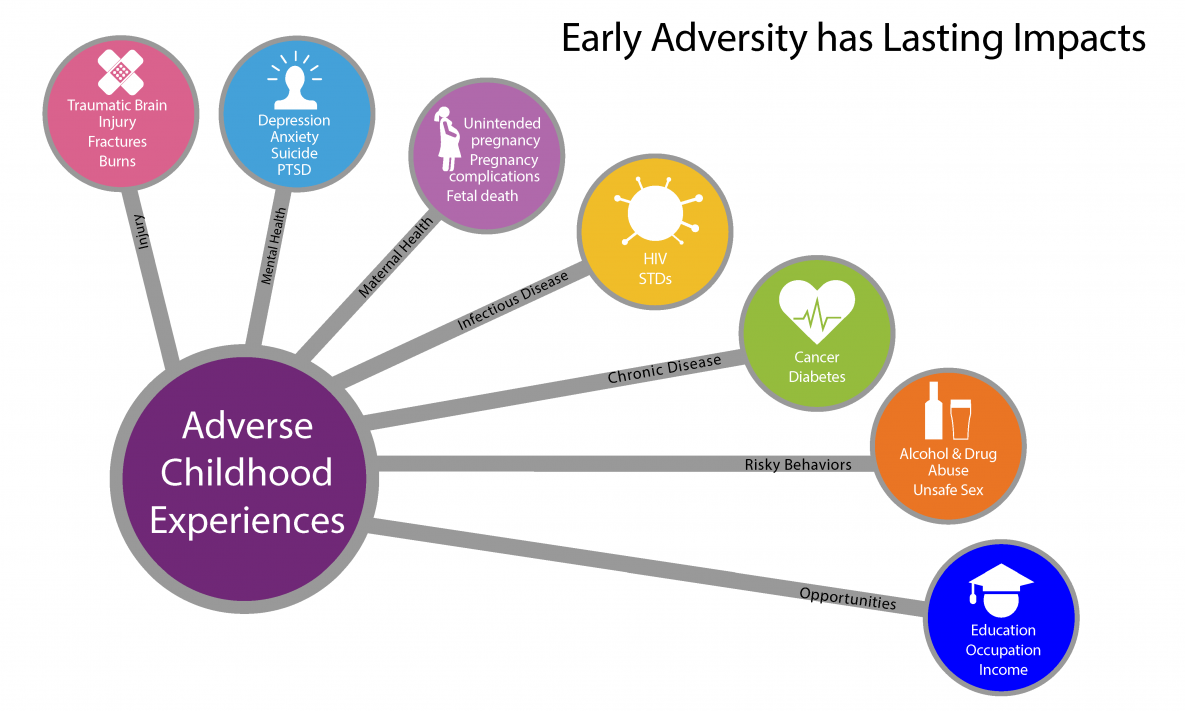

All types of abuse, neglect, and other potentially traumatic experiences that occur before the age of 18 are referred to as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (CDC, 2019). ACEs have been linked to risky behaviors, chronic health conditions, low life potential and early death, and as the number of ACEs increase, so does the risk for these results. When a child experiences strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity without adequate adult support, the child’s stress response systems can be activated and disrupt the development of the brain and other organ systems (Harvard University, 2019). Further, ACEs can increase the risk for stress-related disease and cognitive impairment, well into the adult years. Felitti et al. (1998) found that those who had experienced four or more ACEs compared to those who had experienced none, had increased health risks for alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, suicide attempt, increase in smoking, poor self-rated health, more sexually transmitted diseases, an increase in physical inactivity and severe obesity. More ACEs showed an increased relationship to the presence of adult diseases including heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, skeletal fractures, and liver disease. Those with multiple ACEs were likely to have multiple health risk factors later in life.

According to Merrick et al. (2018), the foundation for lifelong health and well-being is created in childhood, as positive experiences strengthen biological systems while adverse experiences can increase mortality and morbidity. Overall, violence against children has detrimental effects, which can result in long-term negative physical and emotional development.

Human Trafficking

Human trafficking has been referred to as modern day slavery and affects millions of people worldwide, regardless of gender (International Labor Organization, 2020). According to the United Nations (2020):

Trafficking in persons is the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs. (para. 1)

Statistics for human trafficking can be difficult to obtain as survivors of human trafficking are often fearful of seeking help due to threats from their traffickers. According to the International Labor Organization (2020), 21 million people in the world are the victims of forced labor. In the United States, Polaris (2020) operates the National Human Trafficking Hotline, which provides 24/7 support and a variety of options for survivors of human trafficking to get assistance. In 2019, the trafficking hotline received 48,326 individual trafficking-related contacts. Also in 2019, Homeland Security initiated 1,024 human trafficking investigations and recorded 2,197 arrests, 1,113 indictments, 691 convictions and 428 victims were identified and assisted (United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020). Throughout the world, agencies are working together to identify survivors of human trafficking and prosecute the traffickers.

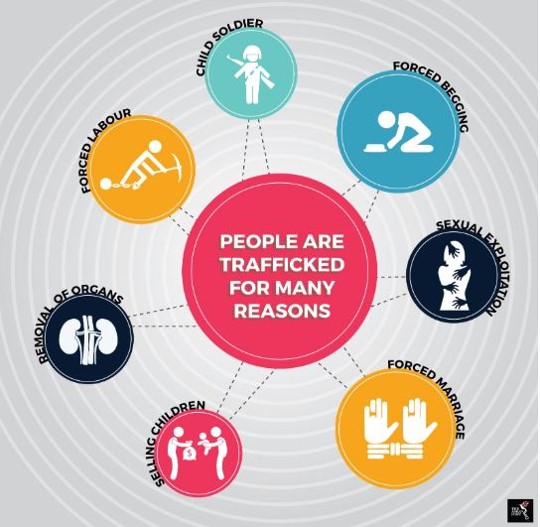

A myth of human trafficking is that female sex trafficking is the main type, and the traffickers are always male (Polaris, 2020). In reality there are many types of trafficking including forced work in healthcare, hotels/motels, house cleaning, agriculture, forestry, construction, landscaping, factories, trucking, child care, massage parlors, pornography, carnivals, outdoor solicitation and begging. Additionally, child soldiers and child brides are included, as well as the removal of organs. Females are overrepresented in sexual exploitation, but males and those who are transgender also are sex trafficked at high levels. Males make up the majority of those in forced labor, as child soldiers, and have their organs removed. Females are also traffickers, and focusing on traditional gender stereotypes ignores the reality that women can be very effective at gaining the trust of survivors and then exploiting them. This includes family members who may sell their children or relatives to traffickers.

Female Survivors of Sex Trafficking:

According to the American Psychological Association (2014), women and children make up the largest group of survivors in the sex trade. The average entry is 13-16 years of age, but girls as young as 10 have been exploited. There are many factors that contribute to sex trafficking females, and the most frequent include:

- Widespread objectification of the female body that creates women and girls as products in the economy

- Glamorization of pimping and prostitution within the culture

- Sexualization of adolescent girls in popular culture

- Pervasive poverty and shifts in economies that force females in rural areas to seek work in urban areas, thus removing them from family and community protection

- Participation in low skilled and low paying jobs that are traditionally associated with female roles of serving and nurturing and thus makes them vulnerable to forced labor

- Use of smugglers to cross into the United States who often work with pimps

- Unstable political environments caused by natural disasters, political conflicts, and wars that disrupt social functioning

- Corruption among all levels of a government

- Residing in a location where large numbers of military personnel were stationed for a long period of time

- History of past abuse, disabilities, language barriers, undocumented status, parents involved in substance use or criminal activity, abandonment, neglect, and being a runaway

Both significant physical and psychological consequences result from surviving sex trafficking (APA, 2014). Physical and sexual violence, including rapes, assault, gunshots, knife wounds, burns and torture are common, and homicides are the leading cause of premature death for those who are sex trafficked. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, loneliness, dissociation, feelings of worthlessness, loss of memory, and negative beliefs about oneself, others and the world are present in survivors. Additionally, many survivors are diagnosed with Complex PTSD, which results from multiple or persistent trauma. A history of abuse and trust in the trafficker through grooming or being known to them, makes the survivor especially vulnerable to complex trauma. Complex trauma affects an individual’s affect regulation, consciousness, self-perception, and relationships with others. Those with complex trauma may turn to substance use, self-abusive behaviors, disordered eating and suicidal gestures.

Male Survivors of Sex Trafficking:

Gender stereotypes reflect the belief that because males are seen as the aggressors, they cannot be trafficked (Raney, 2017). However, this is false as males reside in similar dysfunctional situations to those experienced by girls and women. “Boys and men who have been trafficked present with issues that are similar to many victims of complex trauma: poverty, sexual abuse, violence or living in a home where substance abuse takes place,” (p. 22). Male survivors of sexual trafficking often present with additional trauma and shame as they believe they should have been “man enough” to stop the trafficking and abuse, even if they were a child at the time. Another difficulty for male survivors is the lack of available services as the majority of assistance is focused on female survivors.

Child Brides:

UNICEF estimates that in 2016, 5.6 million girls under the age of 18 became a child bride and more than 650 million women alive today were married before the age of 18 (Reid, 2018). During the past decade, the proportion of young women who were married as children decreased by 15 per cent, from 1 in 4 (25%) to approximately 1 in 5 (21%), and efforts are being made throughout the world to end child marriages by 2030. There are many factors that contribute to child brides including poverty, lower dowry costs, paying off debts, food insecurities, political unions, cultural and social norms, protection during unstable times, and to ensure young females remain virgins as to not dishonor their families.

Regardless of the reason, child marriages are associated with a range of poor health and social outcomes (United Nations Human Rights Council, 2014). These negative consequences include early and frequent pregnancies that are linked to high maternal and infant morbidity and mortality. Pregnancy-related complications are the main cause of death for young women, with girls being twice as likely to die from childbirth as women in their twenties. Girls who are subjected to childbirth early, and forced marriage are often unable to make decisions about their sexual and reproductive health. This compromises their ability to decide on the number and spacing of their children and places them at heightened risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections and HIV. Child marriage and early childbearing are also significant obstacles for participating in education, employment and other economic opportunities.

Although the majority of child brides are located in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (UNICEF, 2018), between 2000 and 2015, at least 207,459 minors were married in the United States (Tsui et al., 2017). The exact number is not known as not all states keep data on the age of those seeking marriage licenses as it is left to individual counties. Almost 90 percent of minors who married between 2000 and 2015 were girls. Although most of them were 16 or 17 years old, some were as young as 12 years old. While some minors married other minors, 86% married adults. Marriages involving minors occurred most often in Idaho, Kentucky, and West Virginia, which have large rural populations and higher levels of poverty. Girls from middle class and wealthy families, as well as those who live in cities, typically do not get married young.

An individual in the United States can marry without parental consent at the age of 18 in all states and at 19 in Nebraska. Underage marriages can occur when there is consent of the parents, consent of a court clerk or judge, if one of the parties is pregnant or has given birth, or if the minor is emancipated (World Population Review, 2020). Most states have a minimum marriage age for minors with parental consent, ranging from 12-17 years old. However, neither California nor Mississippi have minimum ages, and Massachusetts has the lowest minimum marriage age with parental consent of 14 years old for boys and 12 years old for girls. State-wide efforts are underway to raise the age of marriage for all individuals to 18, regardless of pregnancy or parental permission. Advocates of stricter state laws argue that current laws are failing to protect minors from being forced or coerced into marriages where they may face violence and sexual assault (Tsui et al., 2017).

Children who are wed before the legal age of adulthood may face additional legal challenges if they wish to leave the relationship as not all states automatically grant emancipation when a child marries (Tahirih Justice Center, 2017). Should they try to leave a marital relationship even for domestic violence they may find, depending on the state, that they are turned away from shelters as they are below the legal age of adulthood. Tahirih also found that child brides can be listed as a runaway, and if found may be returned to their family and potentially their abuser. In addition, the lack of emancipation may mean that the while the child can be married, they may not be able to file for a divorce, and must rely on the help of an adult to be their advocate.

Gender and Crime Statistics

Statistics from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI; 2018) demonstrate that males commit the vast majority of the crimes in the United States. The following table depicts the most recent data from 2018 identifying the crime and the percent for males and females. Only two of the offenses listed indicate a higher percentage for females than males: embezzlement and prostitution.

Data measuring violent incidents in 2018, indicated that males were offenders in a greater percentage committed against males (81%) and against females (73%) (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2019). Males also experienced higher victimization rates than females for all types of violent crime except rape/sexual assault. Females were more likely to commit a violent act against other females (21%) than against males (16%). Violence in other cultures and countries reflect what is seen in America. Overall, in every society, males are more violent and commit more crimes than females (Kanazawa, 2008a).

What accounts for the significant gender differences in the level of crimes committed ?

According to the University of Minnesota (2015), biological differences are seen by some researchers as reasons, especially the role that testosterone plays in aggression. Gender role socialization is another theory as boys are raised to be assertive and aggressive, while girls are reared to be nurturing and kind. A further reason relates to opportunity, as parents watch their daughters more closely than they watch their sons, thus providing males more opportunities to engage in illegal behaviors, especially within a peer group. Additionally, women face lower incentives to engage in crime as criminal earnings are higher for men, and women with very young children receive more adverse effects, such as going to jail (Campaniello, 2019). The lower rates for women are also due to females being less likely to be arrested, sentenced, and incarcerated for the same crimes compared to males.

Theorists associated with the evolutionary perspective, indicate that the large number of homicides between men, compared to the number of homicides between women, or between the genders, is a direct consequence of males competing for mates (Kanazawa, 2008a). For example, most homicides between men are due to “trivial altercations.” A fight might begin because of trivial matters of honor, status and reputation. One male might insult another or show an interest in the other’s partner, resulting in violence because neither male would back down. Evolutionary psychologists believe that these mostly young men are fighting for status in their peer group because high-status individuals are more sexually attractive to women (Barber, 2015). Nonviolent crimes, such as stealing, are also explained through the evolutionary perspective as a way for males to accumulate resources that attract mates when they lack legitimate means to acquire these resources (Kanazawa, 2008b).

For females, the evolutionary perspective explains that they too may need to compete for resources and mates, especially when these are scarce (Kanazawa, 2008c). They may occasionally resort to violence, but more often spread negative gossip or rumors about a romantic rival than become violent with them. To obtain resources, they are more likely to engage in lower risk acts, such as embezzlement, rather than robbery. When women do steal, they tend to steal what they need to survive for themselves and their children, and they tend not to use crime for other purposes, like showing off and gaining status, as men do.

Despite the current gender gap, the number of women committing crimes is increasing. According to Campaniello (2019), women have more freedom than in the past, which provides more opportunities for crime. Additionally, the relative wage inequality between higher and lower earning women’s wages has resulted in more women at the low end of the wage distribution committing crimes.

Intersectionality and Incarceration

The racial and ethnic makeup of prisons in the United States continues to look substantially different from the country’s demographics. While their rate of imprisonment has decreased the most in recent years, black Americans are much more likely than their Hispanic and white counterparts to be in prison (Gramlich, 2020). In 2018, black Americans represented 33% of those in prison, almost triple their 12% share of the U.S. adult population. Whites accounted for 30% of prisoners, about half their 63% share of the adult population. Hispanics accounted for 23% of inmates, compared with 16% of the adult population.

The racial and ethnic makeup of prisons in the United States continues to look substantially different from the country’s demographics. While their rate of imprisonment has decreased the most in recent years, black Americans are much more likely than their Hispanic and white counterparts to be in prison (Gramlich, 2020). In 2018, black Americans represented 33% of those in prison, almost triple their 12% share of the U.S. adult population. Whites accounted for 30% of prisoners, about half their 63% share of the adult population. Hispanics accounted for 23% of inmates, compared with 16% of the adult population.

Black men especially are likely to be imprisoned. There were 2,272 inmates per 100,000 black men in 2018, compared with 1,018 inmates per 100,000 Hispanic men, and 392 inmates per 100,000 white men. The rate was even higher among black men in certain age groups: Among those ages 35 to 39, about one-in-twenty black men were in state or federal prison (Gramlich, 2020).

Currently, women comprise only 7% of the federal prison population, and they also are a smaller percentage of inmates in state and local facilities. Even though there are significantly fewer female inmates than male, during the past 30 years there has been a 700% increase in female imprisonment in federal, state, and local correctional facilities (Cowan, 2019). While federal prisons have seen an uptick in numbers of incarcerated women during this period, the most dramatic increases are in state prisons and local jails. Although there has been an increase in women convicted of violent crimes, most incarcerated females are serving sentences for property and drug offenses.

Similar to men, women of color are overrepresented in prisons (Cowan, 2019). Black women are twice as likely to be incarcerated as white women: 96 per 100,000 versus 49 per 100,000. Additionally, rates of Hispanic women in correctional settings are 1.4 times higher than those for whites: 67 per 100,000 versus 49 per 100,000. Native American women are also overrepresented in prison in particular geographical locations. Even at the juvenile justice system level, black and Hispanic girls are more likely to be committed to juvenile residential facilities than white girls. What is consistent, is that females in prisons are overwhelmingly poor, with most living well below the poverty line. Because of their overall limited incomes, more women stay in prison without having been convicted of a crime because they cannot afford the cash bond to be released (Sawyer, 2018).

Compared to male inmates, female inmates are more likely to have experienced a lifetime of exposure to cumulative trauma, physical and sexual victimization, untreated mental illness, and substance use to manage distress (Ney et al., 2012). According to Sawyer (2018), women’s responses to gender-based abuse and discrimination are increasingly criminalized, such as fighting back against domestic violence, or running away from abuse for girls. Upon release from prison, rates of relapse are high for women, especially if they have not received the mental health or substance abuse treatment needed during incarceration. Stigma facing female parolees is greater than that facing males. There are fewer halfway programs and shelter beds for women. Female parolees have greater difficulty obtaining employment and housing than males, and are at greater risk for losing their homes (Bandele, 2017).

While incarcerated, women receive more disciplinary actions, and more severe sanctions than men (Sawyer, 2018). Even though female inmates are less likely to act out violently than males, they receive more physical restraints and disciplinary tickets for minor offenses, such as making a derogatory comment, disrespect, or refusing to obey an order (Pupovac & Lydersen, 2018). Critics of female prisons have stated that officers write emotionally driven tickets because they become frustrated and angry with female inmates for talking back or behaving disrespectfully. Women are more likely to have their phone privileges revoked or have visitation privileges with their children cancelled, and they spend more time in solitary confinement. Not surprisingly, these disciplinary actions hinder a woman’s ability to get time off her sentence or be paroled. Critics believe that women are expected to follow strict social controls in prison that would never be accepted by male prisoners.

While incarcerated, women receive more disciplinary actions, and more severe sanctions than men (Sawyer, 2018). Even though female inmates are less likely to act out violently than males, they receive more physical restraints and disciplinary tickets for minor offenses, such as making a derogatory comment, disrespect, or refusing to obey an order (Pupovac & Lydersen, 2018). Critics of female prisons have stated that officers write emotionally driven tickets because they become frustrated and angry with female inmates for talking back or behaving disrespectfully. Women are more likely to have their phone privileges revoked or have visitation privileges with their children cancelled, and they spend more time in solitary confinement. Not surprisingly, these disciplinary actions hinder a woman’s ability to get time off her sentence or be paroled. Critics believe that women are expected to follow strict social controls in prison that would never be accepted by male prisoners.

Approximately 6%-10% of incarcerated women are pregnant (Stringer, 2019). In more than half of U.S. states, women are shackled to the bed during delivery and their baby is taken away and placed with a family member or into foster care. Over 60% of imprisoned women are mothers, and the time away from their children can negatively impact the mother-child bond. Incarcerated mothers may not be able to visit with their children or maintain custody of their children, even if the reason they are in prison has nothing to do with child abuse or neglect. When mothers are in prison, and especially if children are placed in foster care, children are more likely to experience homelessness and later involvement in the criminal justice system themselves (Cowan, 2019).