1.1: Geography and Geo-Literacy

- Page ID

- 147495

- Describe what distinguishes a geographer's approach to examining the world.

- List the sub-fields of geography and examples of their respective topics of study.

- Define geo-literacy and explain the state of geo-literacy among Americans.

- Define and identify world regions and explain some of the challenges of studying the world through regional geography.

- Speculate how geographical knowledge may be powerful and relevant for 21st-century students.

What is geography?

The Latin roots of the word geography translate as “Earth (geo) writing (graphia).” As an academic discipline, geography can be defined as the holistic study of the Earth’s surface and the interrelationships of its human and physical features. Geographers seek to understand the world as an interconnected web where human and physical systems interact at various intensities and scales. Geographical study essentializes spatial variability, or that events, connections, and processes vary within, between, and among places. As such, geographers adopt a spatial perspective, a disciplinary lens focused on explaining what, where, how, and why phenomena are distributed as a way of understanding the world. For example, why are some places more vulnerable to the effects of climate change? Why was the covid-19 pandemic especially deadly in some US counties? What factors explain increased rates of tropical deforestation? Why is there a disproportionately high concentration of pollutants and a lack of trees in many poor urban neighborhoods? These are questions about specific patterns of spatial difference that shape lived experiences in the world. It is from this perspective that geographers study landscapes, pandemics, climate change, population, migration, socioeconomic inequality, biodiversity, agriculture, biogeography, urbanization, and much more.

You might note that other fields might pursue similar research questions and topics. Geography is an interdisciplinary discipline with a lot of commonalities with other disciplines. It also bridges both the natural and social sciences as a way of producing a more holistic understanding. Geographers tend to focus on places, locations on Earth distinguished by cultural and physical characteristics. Geographers seek to understand processes that make places unique or similar to other places and the power of place in shaping experiences and opportunities. Places can also be aggregated into larger spatial units, or regions, an area of the Earth with one or more shared characteristics. Geographers divide the world into regions such Europe or East Asia, or more localized regions such as Southern California or the African Sahel, for example. Regions are based on selected cultural, historical, functional, and/or environmental similarities of places. The geographical units of regions can vary in scale, the portion of Earth being studied. Geographers study in a variety of scales, from local to global. Many of our contemporary issues are global in scale, such as climate change and biodiversity loss. However, global issues have complex localized contexts, and geographers often study the relationship of global and local phenomena. The discipline’s holistic approach treats spatial units as connected pieces of a greater whole, focusing on connections among peoples and environments. While geographers often isolate geographical units of the world in their analyses, studies of the world’s interconnectedness, how its human and physical features are intertwined, are what makes geography unique, relevant, and powerful. No other academic discipline takes such a comprehensive approach.

Sub-fields of Geography

Geographers tend to specialize in certain spheres of geographical inquiry, generalized into the following sub-fields:

- Physical geography explores natural processes and patterns of the physical Earth. Physical geographers study topics such as plate tectonics, climate, biogeography, hydrology, and geomorphology to better understand the dynamics of the Earth’s natural environments.

- Human geography explores the human processes and patterns of the Earth. Human geographers study topics such as population, migration, language, religion, place, spatial inequality, economics, development, urbanization, and geopolitics to better understand the forces shaping diverse and inequitable human experiences in the world.

- Environmental geography explores human-environment interactions. Given the immense human impact on Earth’s natural systems, environmental geographers often focus on understanding the causes and consequences of environmental problems. These include deforestation, climate change, biodiversity, water distribution, soil erosion, food systems and a variety of sustainability issues such as green energy, walkable cities, environmental justice, etc.

The interconnectedness of geography often requires geographers to train across geographical subfields (to at least some degree). Some observers have perceived this as a weakness. Geographical studies run the risk of being “a mile wide and an inch deep” since geographers tend to study topics more broadly (and therefore less in depth) than other disciplines might. Nonetheless, geographers have argued that this breadth is a strength and a defining characteristic, creating an integrative disciplinary approach that distinguishes geography from other fields of study.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=807&height=540)

World Regional Geography

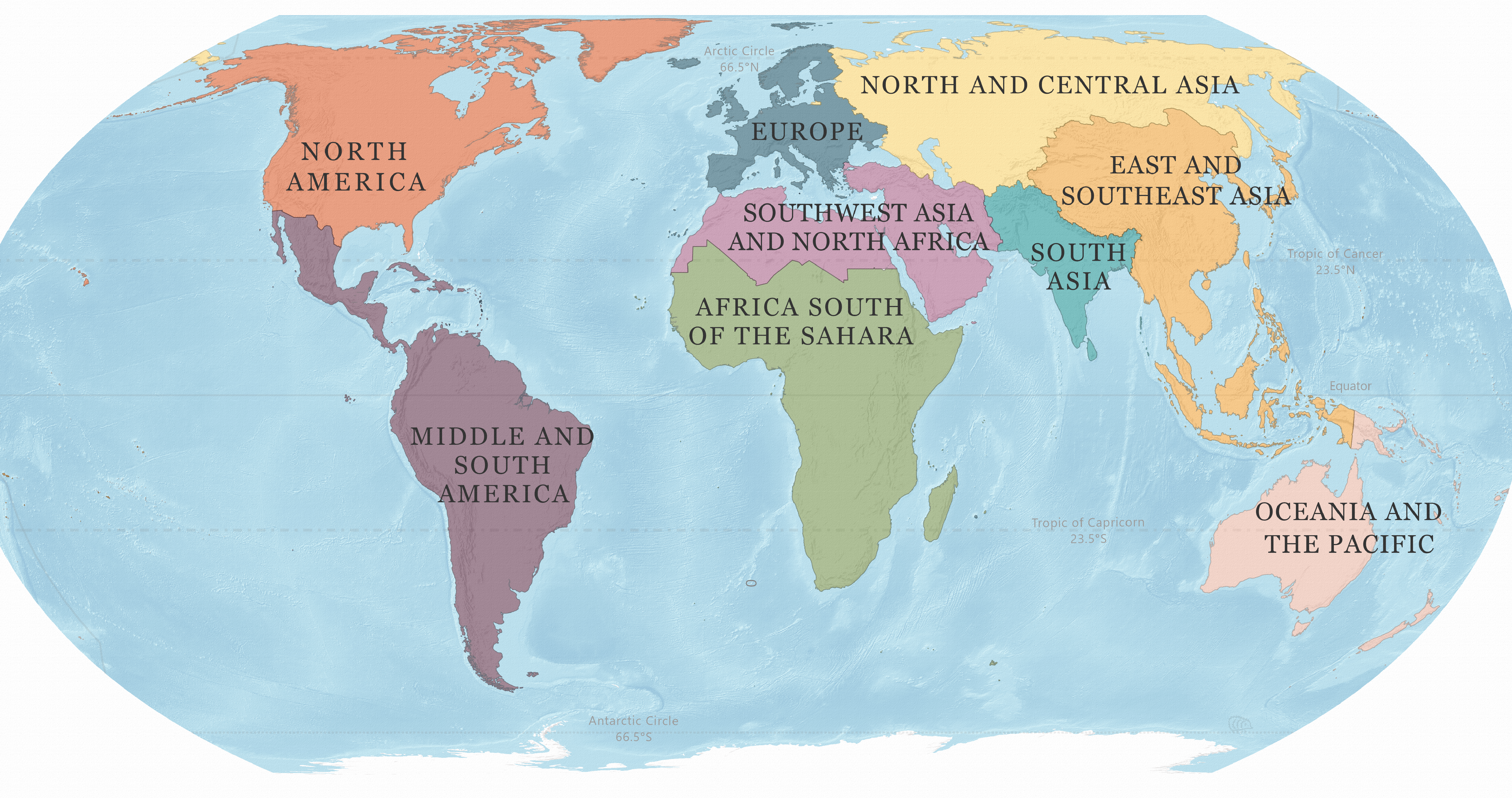

In a world regional geography course, we explore topics across physical, environmental, and human geographies in the context of regions. Regions are land areas with characteristics that distinguish them from surrounding areas and thus group them together. These can be physical, geological, cultural, historical, economic, demographic, and so on. There are several types of regions that geographers use in their regional studies. Formal regions are clearly defined by political or natural boundaries. One example would be Los Angeles, defined as a basin or as a city since both have a well-defined geographical area. Functional regions are defined by the spatial connections of an area. Los Angeles, for example, functions well beyond its defined borders, with a system of freeways connecting commuters and trade to nearby urban centers. Economic, infrastructural, and cultural connections means that the LA area functions over a broader region that includes areas around LA, what we might refer to as a metropolitan area. The city is also part of Southern California, which is a vernacular region, based on socially constructed perceptions of an area, bound together in this case by sunshine, palm trees, beaches, and highways. We all use vernacular regions based on the collective or culturally based associations and understandings that we form about places, like the characteristics we highlight to differentiate North, Central, and Southern California.

While we use these examples to exemplify the types of formal, functional, and vernacular ways we might organize space, we could use regions to make sense of the Earth using varying scales. Regions can be as focused as a neighborhood or a small city or include multiple countries. World regions are among the broadest spatial units that geographers use. If we imagine the world as one interconnected “global village,” then we can imagine that each world region is a neighborhood in that village, neighborhoods with names like South Asia or North America. Each of these neighborhoods share some degree of similarity across their histories, environments, cultures, and economies, leaving a unique spatial imprint on our planet. Studying world geography is a way to identify these various regions and understand their physical, cultural, and political characteristics. As such, in World Regional geography we read the world as a diverse collection of interconnected parts to identify qualities that set world regions apart, the processes that shape these qualities, and the relationships they share with other regions and places.

What Makes a World Region?

The dividing up of our planet into regions requires geographers to apply consistent criteria to justify their choices. Our planet is diverse. We have diverse biomes, or natural regions with distinguishable climate and weather patterns, vegetation, and animal life. We also have diverse cultures, histories, demographic patterns, and cultural, economic, and political systems. Yet, geographical similarities exist across places, which leads geographers to attempt to understand them as aggregates. For example, North American students might easily recognize the characteristics that set the US and Canada apart from the remainder of the Americas, pointing to the English language, temperate climates, and the global influence and affluence of US and Canada. At the same time, students might struggle with placing Mexico. Physiographically it is part of North America. It also shares a history of Spanish colonization with the American southwest, and it is economically tied with US and Canada. Many counties in the American southwest are also predominantly Hispanic and Spanish-speaking. Thus, depending on what characteristics are emphasized, Mexico could be studied in the context of North America, or it could be considered as part of Middle America based on strong cultural and historical ties with that region.

Regions are not always bound neatly by geographical proximity. For example, physical geographers often dissect the world into natural regions based on patterns of temperature and precipitation. As such, we can identify the tropical regions near the equator, with warm and wet climates and lush vegetation spanning across the Americas, Africa, and South and Southeast Asia. Similarly, expansive deserts can be found in the mid-latitudes across the continents. This spatial pattern is visible in satellite images, with green equatorial regions that transition into barren landscapes along the mid-latitudes. When thinking of human characteristics, too, geographers often use various transcontinental regions. Take for example the term “the Muslim world,” a term used to identify places with large Muslim populations. This cultural region sweeps North Africa, Southwest Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Other terms like “high income countries” or the “Spanish speaking world” are examples of how we mentally aggregate places based on selected similarities. In other words, regions are creative imaginings of geographical contexts, constructed spatial aggregates. As such, we should think of them as dynamic entities, constantly changing over time, and always subject to perspective, historical context, and decision making.

World Regions as Generalizations

World regions are a form of spatial heuristics (heuristics is a Greek word for “I find, discover”), and, for our purposes, it means a cognitive shortcut to come to a short-term conclusion. World regions are intellectual tools for classifying and organizing places both physically and in our imagination. It is important to recognize, however, that dissecting the world into world regions results in broad generalizations. While they are useful for synthesizing spatial variability across the vast Earth, there is great diversity in physical, cultural, functional, and historical factors within regions that drives geographers to “zoom in,” or examine phenomena at finer scales to better understand more localized contexts and places.

Each of the world regions can be and often are divided into smaller regions and sub-regions. For example, in this book we explore East and Southeast Asia as one world region. Each of these could instead be declared its own region, based on unique distinguishing characteristics. There is not a single world region that demonstrates physical or cultural homogeneity, they are instead immensely diverse, or heterogeneous, and geographers often use sub-regions to make sense of the diversity within regions. Africa South of the Sahara, for example, can be further regionalized into east Africa, south Africa, west Africa, and central Africa. Europe, too, could be studied in sub-regions like Scandinavia or the Mediterranean, places with distinctive cultural and environmental features that bind them together. We titled this book World Geographies because regions aggregate diverse spatial contexts, and there is no such a thing as a singular world geography nor a homogenous world region.

There might be times when generalizations about a specific unique place on the planet might be helpful, and there are other times when generalizations can be limiting and can even turn into stereotypes. Thus, regional studies have fallen in and out of favor among geographers as we debate how a region is to be represented and how these representations impact how that part of the world is understood. For example, designating the “rust belt” as an economic region in the the Mid-Western US carries negative connotations of abandoned or disinvested places and suggests areas such as Pennsylvania or Ohio are in decline. These generalizations are based on facts and historical processes but are subject to debate because they are one-dimensional social constructions. In other words, they tell a single story of economic decline without contextualizing other cultural and environmental characteristics that make the region more than just the “rust belt.” This exercise in labelling also shows the power and importance of naming. What and how we choose to name places matters. Regional geography always runs the risk of flattening multi-dimensional geographical contexts for the sake of focus and simplification. Even as we make our best attempts at a multi-dimensional approach to world regions, keep this tension in mind as we move forward through the chapters in this textbook.

Boundaries and Transition Zones

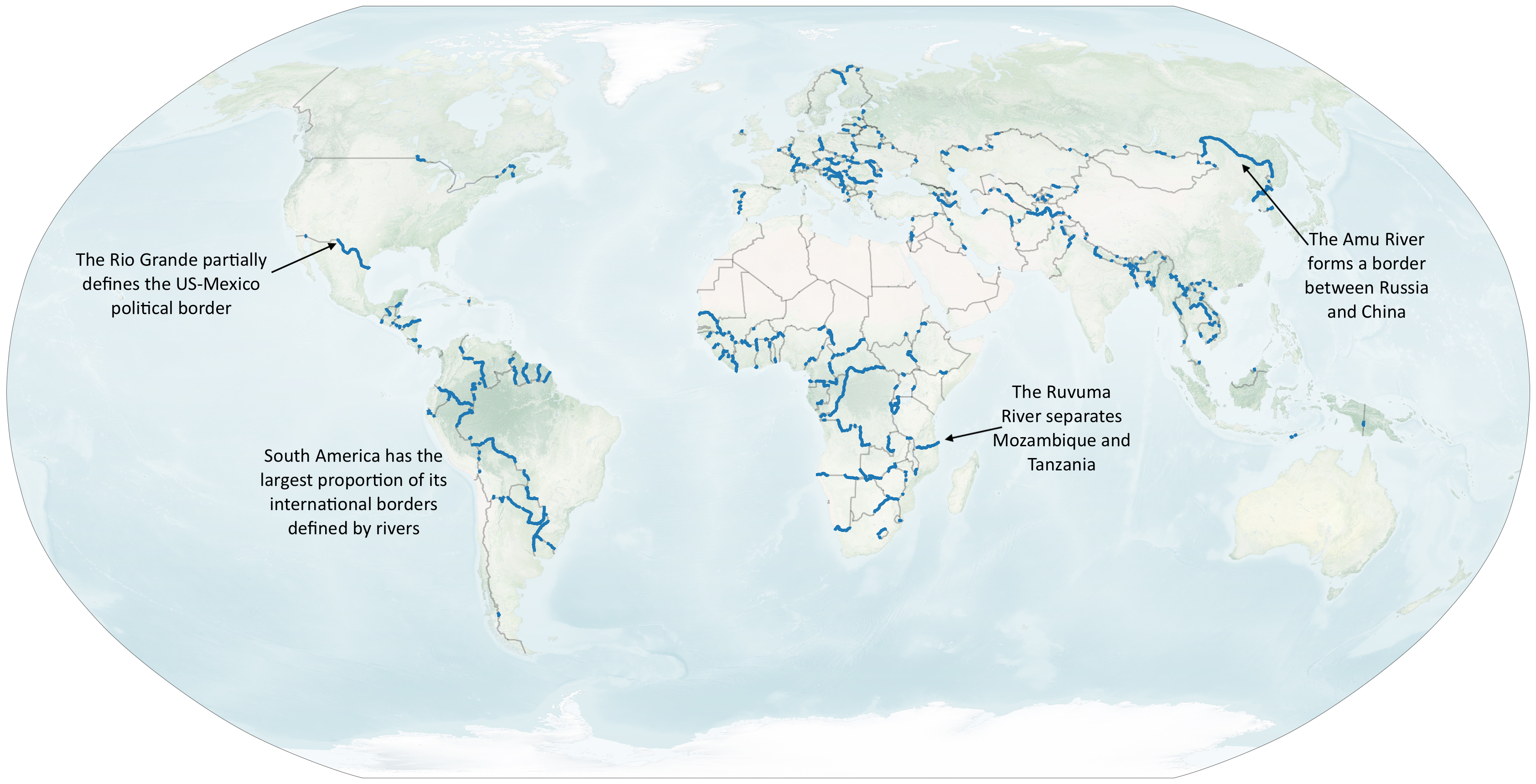

Geographers study world regions as spatial units bound by some sort of natural or political delineation. When you look at Figure 1.1.2, what do you notice about the natural features that separate regions? Perhaps you noticed how water bodies serve as natural boundaries, or separations, that help spatially define each realm. For example, the Atlantic Ocean separates the Americas from Africa and Europe, and the Pacific Ocean separates them from Asia. These oceans remained a formidable barrier to the connections between Eurasia and the Americas for millennia. The separation of the continents was driven by the forces of plate tectonics that over millions of years broke up the supercontinent of Pangea into the landmasses we recognize today. However, world regions are not continents. Some continents contain several world regions, sometimes delineated by physical features, like deserts, mountains, or rivers. For example, rivers form about 23 percent of the world’s international borders. Rio Grande partially forms the border between Mexico and the US, the Amu River between China and Russia, and the Ruvuma River separates Mozambique and Tanzania (See Figure 1.1.3).

Boundaries, however clear they might seem, are not clear-cut lines of physical separation. World regions cannot be dissected from their connections to our larger interconnected planet, so we can think of the boundaries where two or more regions meet as zones of gradual transition. These transition zones are marked by gradual spatial change among cultural and environmental characteristics. For example, the Sahara Desert is a physical feature diving Africa into two distinctive regions north and south of the Sahara. The Sahel is a transitional belt in the southern limits of the Sahara, where the climate transitions from arid to semi-arid before it becomes humid further south. The Sahel is also home to a cultural transition zone where the predominant religion of the north, Islam, coexists with the predominant religion of the south, Christianity. Sahelian countries tend to have an evenly split Muslim and Christian population. These transitional spaces are at the crossroads of world regions and are thus difficult to categorize.

Political borders are often arbitrary lines that abruptly sever natural and cultural landscapes. The United States, for example, shares political borders with Canada and Mexico. The Canadian-US border is the longest international border in the world and was closed off after the September 11th attacks and as a response to the COVID-19 global pandemic. The US-Canada border severs six federally recognized tribal lands, including the Akwesasne Mohawk territories. The Akwesasne territories span New York state and the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec on both banks of the St. Lawrence River. Thus, the political boundaries of the two countries do not correspond with established Indigenous geographies. This is also true along the Mexico-US border where it bisects the Tohono O’odham Nation of southern Arizona and northern Mexico (See Figure 1.1.4). For thousands of years, O’odham people crossed the Sonoran Desert freely, both before and after the US-Mexico border imposed upon their ancestral lands. Today, the Indigenous Nation controls about 75 miles of the highly contested border region, even as fences, walls, and border security have continued to expand over the last three decades. O’odham leaders have resisted the construction of physical barriers severing their lands, noting threats to migratory wildlife and damage to sacred sites, including sacred water springs and burial sites.

The connections between US and Mexico can also be noted in the contemporary relationships between the two countries. At the San Ysidro port of entry, many US and Mexican citizens cross daily, helping to make the US-Mexico border the most frequently crossed political boundary in the world. Many businesses in San Diego are dependent on manufacturing in Tijuana. Tijuana is also a popular destination for American tourists who visit the city for its nightlife and cultural attractions or to fly out to other parts of Mexico, a top destination for international travel for Americans. The Tijuana Cross-Border terminal represents a bi-country airport where travelers can board in terminals in San Diego but take-off from the runaway in Tijuana. These are a few examples of how San Diego-Tijuana represents a transitional space with so many lines of connections that permeate an increasingly fortified border zone.

Many of the world’s borderlands, land areas around political borders, are tense spaces. The borders of Morocco-Western Sahara, for example, were drawn based on European interests and continue to be fervently contested. Similar tensions around colonial borders exist in many parts of the world, notably in Africa South of the Sahara and in South Asia. As we write today, Russia is fighting a war of conquest to expand its borders and claim Ukraine. The state of Israel continues to expand its claims to territory into the West Bank, beyond internationally recognized cartographic borders. In Europe, too, borders have not been fully settled. The country of Cyprus’s capital Nicosia is the only divided capital in the world - North Nicosia is the capital of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, a state only recognized by Turkey with a mainly Turkish population, while southern Nicosia is the Republic of Cyprus home to Greek Cypriots. Geographic borders change, they are fluid and dynamic, and they can be the source of violent conflict. Dividing up land and deciding who the land “belongs” to is one way we witness the spatial materialization of power.

Geo-literacy & Geography Education

Studying world geographies is an opportunity to build geo-literacy, or a basic understanding of how the world works. The National Geographic Society describes geo-literacy to be encompassing of three general concepts, something they call “the three I’s”: 1) that the world is interconnected, or that we interact and connect with peoples and environments in other places, often economically and culturally; 2) that nature and society are interacting systems; and 3) that these connections and interactions between people and places often result in implications, including socioeconomic and environmental issues. Studying geography could entail researching how energy use in the US impacts various parts of the world; how countries disproportionately contribute to and are disproportionately burdened by climate change; the causes and consequences of a global crisis of refuge; or the historical and geographical processes that enable empires to rise and fall. These explorations are examples of how geographical studies explore the connections between places, the interactions of human/environmental systems, and their associated real-world implications. These elements of geo-literacy make it a fundamental skill to help us make sense of the world and envision solutions to its most pressing challenges.

Americans & Geo-literacy

Geography has been called the “unloved stepchild of American education”[1] - only six states in the US require geography stand-alone courses in fundamental education and out of the nine areas listed as core academic subjects, geography is the only one that does not have a dedicated federal program and funding for research or innovation. As a result, many college students in introductory geography classes have no background in the discipline.

The institutionalized neglect of the discipline of geography in the US education system has a dire impact on geo-literacy among students. The 2018 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), known as “The Nation’s Report Card,” indicated that less than 25% of American students were proficient in geography, that is, able to perform at the level expected for their grade.[2] In 2019, NAEP announced geography would be eliminated from its assessments. Similarly, the Survey on Global Literacy by Foreign Relations and National Geographic Society (2016) assessed the understanding of college-aged adults on basic global literacy and issues of pertinence to the United States. Questions inquired about American military alliances, locations of countries where the US has long-standing military involvement/tensions (such as Iraq, Afghanistan, and Iran), and global issues such as climate change. The results showed “significant gaps between what young people understand about today’s world and what they need to know to successfully navigate and compete in it. On the knowledge questions asked, the average score was only 55 percent correct. Just 29 percent of respondents earned a minimal pass..."[3]

We share these findings not to shame or discourage novice geography learners. Instead, we intended to explore some national indicators to shed light on the state of geo-literacy and provide some explanations for why geography is a weak spot for many American college students. At the same time, while levels of geo-literacy vary among individuals, everyone has geographical experience. May it be through the migration stories in our family trees, our local or distant travels, our participation in our communities, or the bits and pieces of information that we put together to make sense of the world. A geography education can be an opportunity to subject our knowledge and perceptions to scrutiny and to consider new information, ideas, and perspectives as a part of the journey for learning and growth. We invite you to come as you are. Let us engage in the vulnerable act of learning, in shared openness and humility. It is in this demeanor that we believe we can best nourish the ongoing act of learning and growth.

Beyond Geo-Literacy: Powerful Knowledge

“Whether it is through appreciating the beauty of Earth, the immense power of Earth-shaping forces or the often ingenious ways in which people create their living in different environments and circumstances, studying geography helps people to understand and appreciate how places and landscapes are formed, how people and environments interact, the consequences that arise from our everyday spatial decisions, and Earth’s diverse and interconnected mosaic of cultures and societies. Geography is therefore a vital subject and resource for 21st century citizens living in a tightly interconnected world. It enables us to face questions of what it means to live sustainably in this world. Geographically educated individuals understand human relationships and their responsibilities to both the natural environment and to others…” – International Charter on Geographical Education, 2016.[4]

Like language literacy, the ability to read combinations of words does not necessarily result in comprehension of the complex ideas in a text. While literacy is essential in retrieving written information, it is a basic skill. Literate students continue to enhance their knowledge and abilities through practices and skills building that helps them think beyond their own experiences. Education sociologist Michael Young has argued that a meaningful education should instill powerful knowledge, or subject knowledge that provides more reliable explanations about the world and intellectually empowers those who attain such knowledge. Maude argues[5] that geographical knowledge empowers us by...

- providing new ways of thinking about the world. Everything exists and happens in a given place, each place is unique, and the characteristics of places can provide at least partial explanations for the outcomes of environmental and socioeconomic processes. A focus on spatial variability is practical and provides a unique way of seeing and explaining the world.

- providing ways to analyze, explain, and understand the world: 1) through comparative analysis, noting how places may be similar and/or different; 2) through explanatory concepts, explaining causal connections and mechanisms that shape places; and 3) through generalizations, or synthesizing a lot of information to discern, compare, and question geographical contexts and phenomena.

- enabling us to find, evaluate, question, and use knowledge to challenge those in positions of power. Thus, this knowledge is powerful because it is not restricted to the powerful, engaging learners with how knowledge is produced, vetted, and applied in decision making.

- enabling engagement in debates on significant local, national, and global issues. The ability to integrate scientific knowledge of topics of great relevance, in both the social and natural sciences, enables learners to attain a holistic understanding that equips them to participate in pressing societal issues.

- providing knowledge of the world. Geography teaches us to think beyond our individual experiences and helps us identify our connections to distant places and peoples. This knowledge stimulates curiosity and appreciation and improves our sense of global citizenship.

Learning geography ought to be powerful. And it is powerful specifically because we are enveloped in real-world geographical experience and real-world challenges. Amidst the climate crisis, the inequities highlighted and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, global declines in human freedoms, unprecedented levels of economic inequality, persistent violations of human rights, and so many other indicators of a world in disarray, the need to connect with and beyond (y)our individual experience to thinking critically about the world, to expand (y)our circles of compassion, and to engage in solutions for a brighter future has never been more urgent. As Derek Alderman, a former president of the American Association of Geographers, highlighted: "Absent, at least prominently, within standard definitions of geographic literacy is the relationship between geographic education and the promotion of peace, social and environmental justice, and anti-discrimination—the very matters that seem to matter the most at this historical juncture…” [6] This kind of geographical knowledge is a core element of a meaningful education and an essential component of world-making.

A failure to maximize geography classrooms to advance this mission is extremely consequential. As Harm De Blij wrote in his book, Geography Matters, “the American public is the geographically most illiterate society of consequence on the planet, at a time when United States power can affect countries and peoples around the world.” Economic and political decisions made in the US have far-reaching consequences. We share this planet and its precious resources with billions of others, and yet have a disproportionate hand in many of its contemporary issues as we consume more resources and exert most military power/influence on international matters. Improving geo-literacy through geographical knowledge means that individual Americans can leverage their centrality and influence with greater global citizenship, stewardship, and accountability. We look forward to maximizing the opportunity.

References:

[1] Finn, Chester E. 2020. Geography: The Unloved Stepchild of the American Education.

[2] NAEP’s 2018 Report Card: Geography.

[3] Council on Foreign Relations & National Geographic, 2016. What College-Aged Students Know About the World: A Survey on Global Literacy.

[4] Commission on Geographical Education of the International Geographical Union. International Charter on Geographical Education. 2016.

[5] Alaric M. 2016. What Might Powerful Geographical Knowledge Look Like? Geography 101 (2).

[6] Derek A. 2018. Time for a Radical Geographic Literacy in Trump America. American Association of Geographers Newsletter.

Attributions:

“Kant’s Three Ways of Ordering Knowledge” by Mark Conson, William Doe, Michael Thomas, and Greg Thomas, Penn State University (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Sub-fields of geography is adapted from “History of the Geography Discipline” by Darstrup (CC BY 4.0).