7.2: Indigenous Worlds: Cultural Hearths, Empires, and Colonial Legacies

- Page ID

- 147523

- Describe the characteristics and significance of the Indus Civilization.

- Describe the monsoon navigational routes and the ancient trading networks of the Indian Ocean.

- Explain motivations and methods of European colonialism in South Asia.

- Describe the underlying factors that led to the Partition of 1947 and its long-lasting impacts.

- Evaluate legacies of British colonialism in South Asia.

Ancient Civilizations and Empires

Indus Civilization

The Indian subcontinent has a long history of human occupation. The earliest known civilization on the subcontinent was the Indus Valley Civilization (3300 BCE to 1500 BCE) that flourished along the floodplains of the Indus River, in modern-day Pakistan and northwest India. It is considered one of the world’s earliest civilizations, akin to Mesopotamia in terms of its early innovations, starting with the domestication of crops around about seven thousand years ago. Regarded as a cultural hearth, the Indus civilization served as a hub of innovation where ideas originated and disseminated from. Remnants of the ancient Indus Civilization feature sophisticated architecture and meticulously planned cities, characterized by grid-like street layouts, sewage systems, and multi-story brick houses. In addition to being known for its refined urban planning, the Indus civilization developed one of the world's earliest writing systems, a script that has yet to be deciphered, known as the Indus or Harappan script.

Agriculture, architecture, and writing are hallmarks of social complexity found in many of the world’s cultural hearths. However, unlike other great early civilizations, there is a clear lack of evidence of elaborate tombs, individual-aggrandizing monuments, large temples, and palaces. Early excavations of the region led scholars to conclude that the Indus civilization was far more egalitarian, more equal, than other early complex societies of the time. Despite nearly a century of research and exploration, there is still no clear evidence that a ruling class of managerial elite existed.[1] This is significant because the absence of a discernable wealthy elite challenges the notion that all social complexity arises from stratified social relations and hierarchies of wealth. It could be that the accumulation of resources, wealth, and power in the hands of a ruling class was absent from the Indus civilization. Instead, architectural ruins at Mohenjo Daro, one of the best-known excavated cities of the Indus Civilization, showcases a focus in great public works. The finest structure resembling the glory of a temple is a large public bath built in the center of the city, known as The Great Bath. It is one of the earliest known examples of public bathing and a testament of the importance of public works and communal structures in this early civilization. It is also suggestive of the ancient roots of bathing as a religious ritual, still practiced by both Hindus and Muslims in South Asia.

Between c. 1900 - c. 1500 BCE, the Indus civilization began to decline for unknown reasons. Scholars believe it may have had to do with climate change, the drying up of the Sarasvati River, an alteration in the path of the monsoon rains, overpopulation, a decline in trade, or a combination of any of the above.

The Mauryan and Mughal Empires

The northern plains of South Asia, which extend through the Ganges River valley over to the Indus River valley of present-day Pakistan, were fertile grounds for several empires that controlled the region throughout history. The Mauryan Empire (322-185BCE) was one of the most extensive and powerful political and military empires in ancient India. It was a prosperous empire that greatly expanded the region’s trade, agriculture, and economic activities. One of the greatest emperors in the Mauryan dynasty was Ashoka the Great (268-232 BCE), who ruled over a long period of peace and prosperity. Ashoka embraced Buddhism and focused on peace for much of his rule. He created hospitals and schools and renovated major road systems throughout the empire. His advancement of Buddhist ideals is credited with being the reason most of the population on the island of Sri Lanka is Buddhist to this day.

Islam diffused to South Asia through trade and invasion and became powerful force in the region. Muslim dynasties or kingdoms that ruled India between 1206 and 1526 are referred to collectively as the Delhi Sultanate. The Delhi Sultanate ended in 1526 when it was absorbed into the expanding Mughal Empire. The Islamic Mughal Empire (1526-1857) governed a vast empire encompassing territories from modern-day Iran and Afghanistan to Pakistan and Uzbekistan, and nearly the entire Indian subcontinent. The Mughal empire represents one of the largest centralized states in the pre-modern world, with a territorial expanse covering most of the Indian subcontinent from the Indus River Basin, Afghanistan and Kashmir to present-day Assam and Bangladesh highlands – a territory with a population of about 100-150 million in 1700s. It commanded resources unprecedented in Indian history and, in sheer size, surpassed its two rival Islamic empires - Safavids and Ottomans, being comparable only to Imperial China of the time.

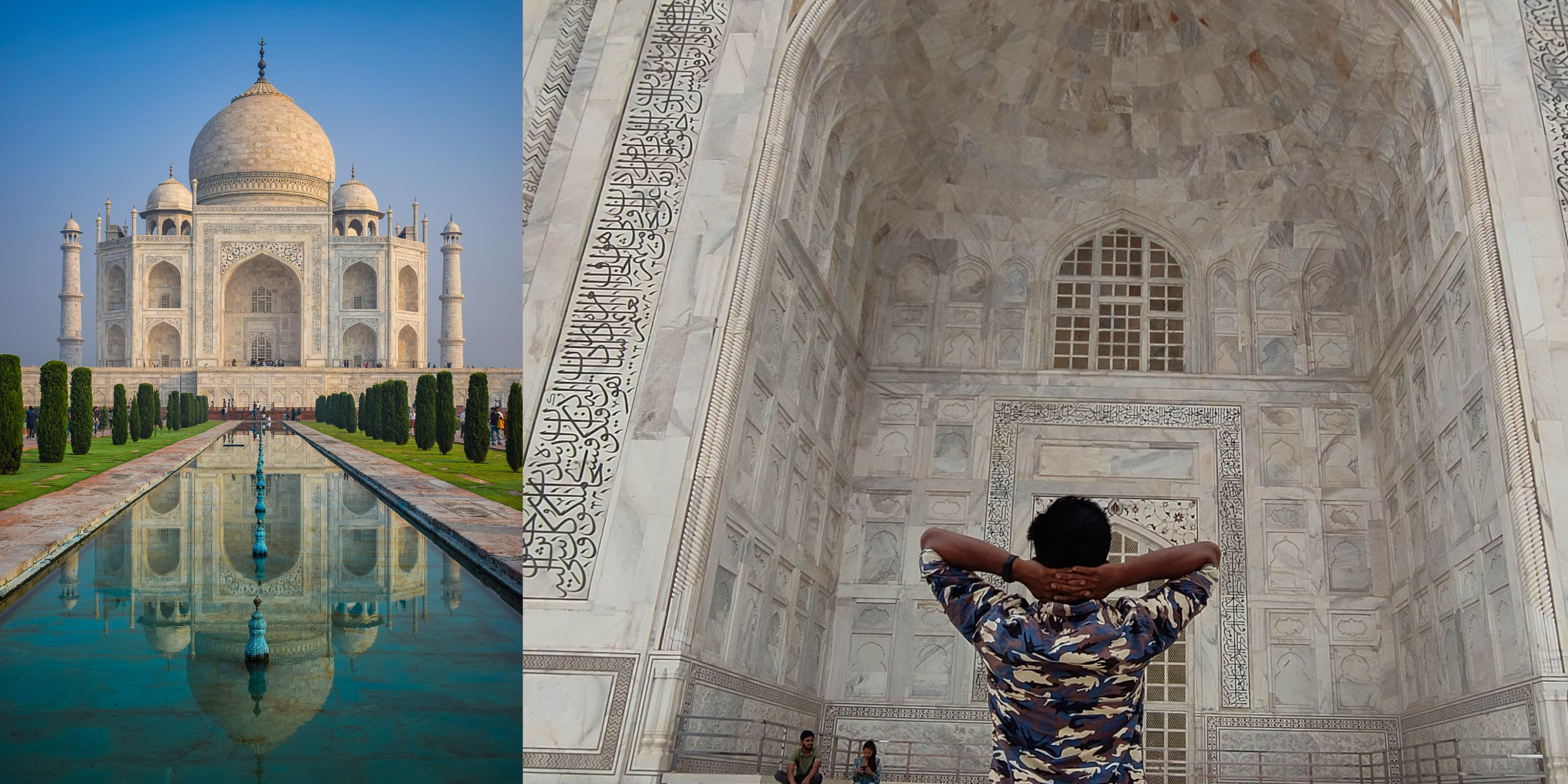

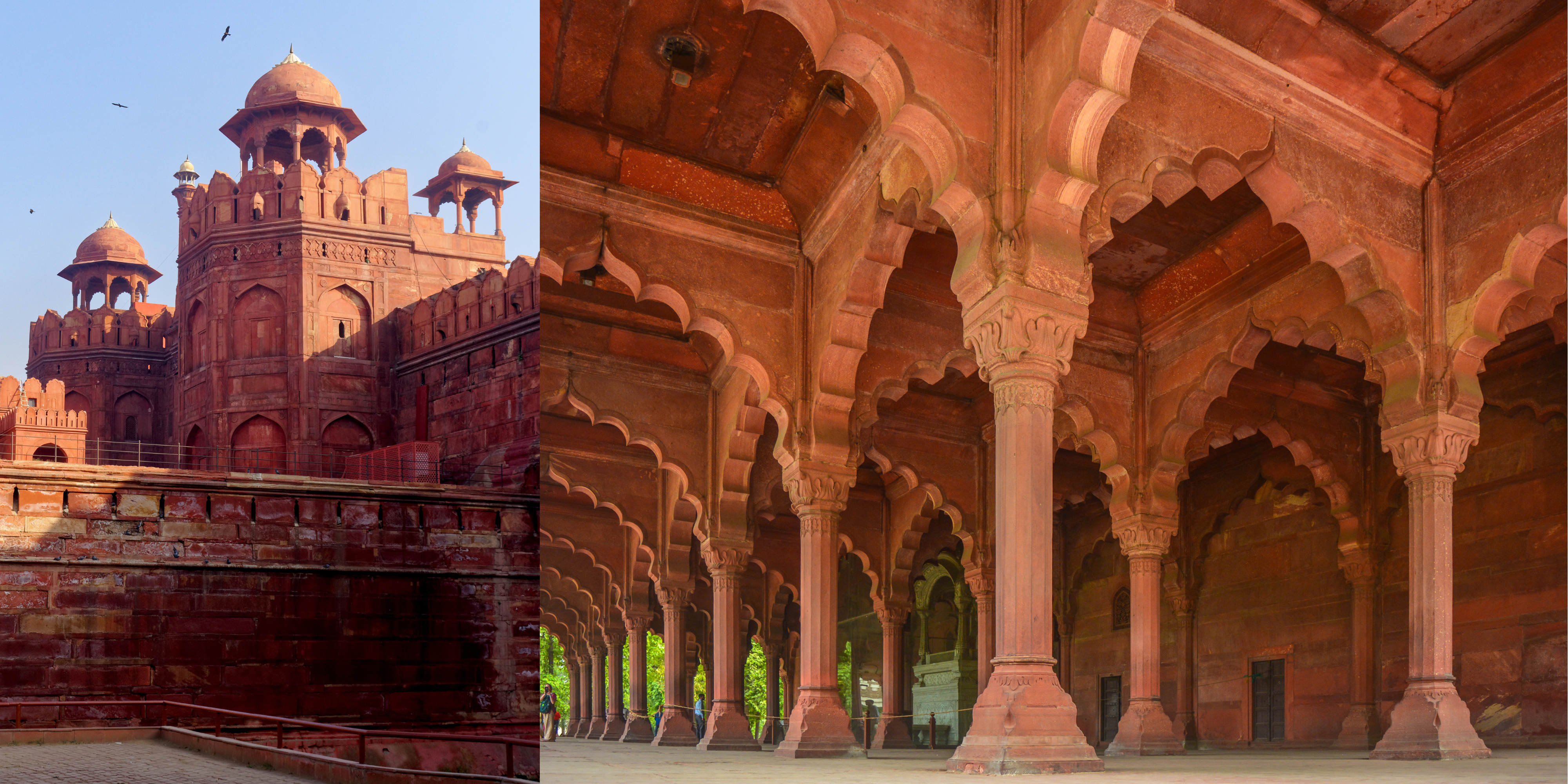

The Mughals' reputation for their military might and trading prowess, coupled with their religious tolerance for other faiths and appreciation for the arts, earned them widespread recognition. They are also recognized for their distinct architectural skills and design. They built many of the monuments we associate with India, including the Taj Mahal, the Red Fort in Lahore, and the Agra Fort.

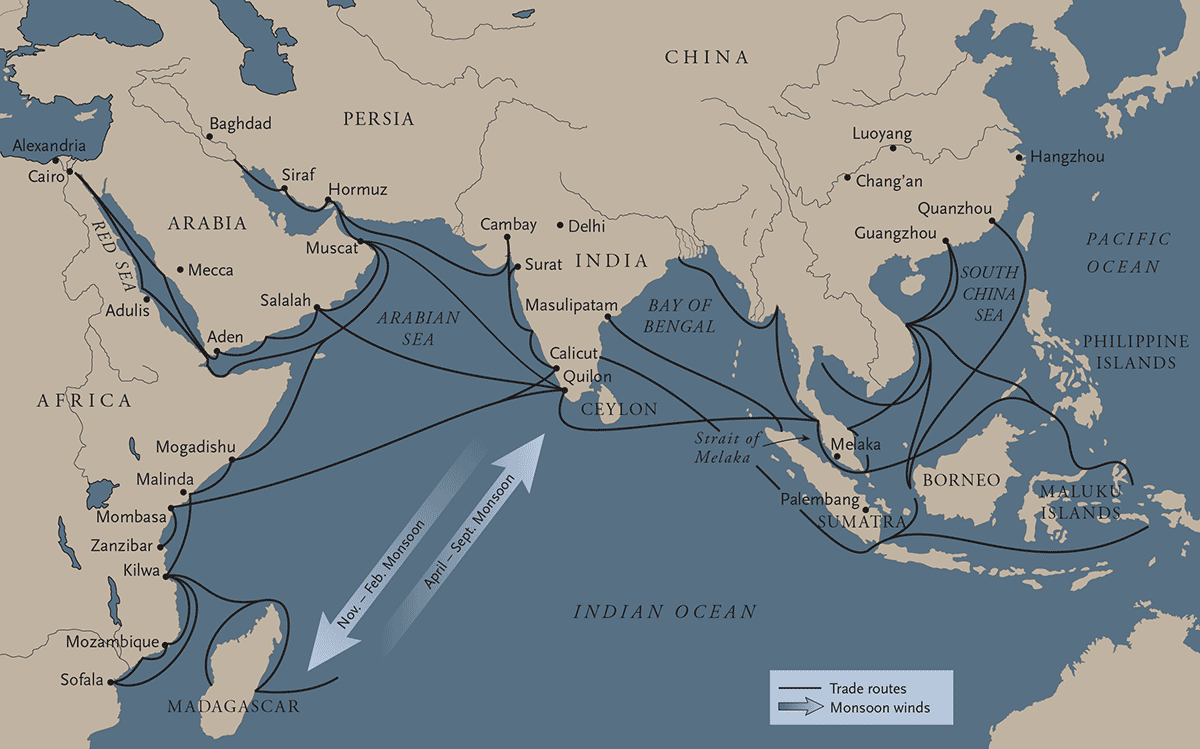

The Indian Subcontinent has a vast coastline surrounded by the waters of the Indian Ocean. Merchants sailed these waters for at least two millennia (until the 16th century), interconnecting East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and Asia in cultural and material exchanges that tied peoples from distant lands through an Indian Ocean network. These exchange networks were developed by skilled sailors who understood how to harness the changing monsoon winds for navigation in traditional vessels generally known as dhows, a Swahili term.[2] From April to September, the monsoon winds rush towards Asia, enabling sailing from East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula towards Asia. From November to February, the winds shift in direction enabling a return. Harnessing the winds for navigation meant that it was the seasonal patterns of the monsoon that dictated when sailors could travel east or west, limiting travel frequency and prolonging stay until the winds changed. Sometimes having to wait for months, merchants mingled around their trading posts resulting in a greater cultural exchange amongst peoples in East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, Persia, India, and beyond to China and southeast Asia – peoples that were otherwise separated by a vast ocean.

The precolonial monsoon market moved an array of goods, including aromatic oils, precious stones, glass beads, pottery, enslaved persons, grains, textiles, and spices.[3] Protruding into the middle of the Indian Ocean, the eastern and western shores of the Indian Peninsula are centrally located in this ancient network of commerce. India’s Malabar Coast (in the southwest) was well known as the world’s hub for pepper and fine textiles, attracting traders from afar in search for these highly prized goods. Abundant with variety of superb timber, the Malabar Coast was also the center of shipbuilding. Indian shipwrights mastered the construction of traditional vessels in teak, a highly durable hardwood. These ships varied in size and types, but some were large sea-faring vessels capable of transporting elephants and hundreds of passengers.[4] Navigational expertise too was well-rooted in Indian maritime traditions, and Indian navigators dominated the waters of the Indian Ocean (along with their Arab counterparts). All aspects of this maritime tradition were unwritten, entirely passed from one generation to the next as a way of life. These ancient cultural and economic systems that were devasted with the advent of European colonization.[5]

Colonization of South Asia

Asia was at the center of European colonialism and the history of globalization. It was the lure of spices, in high demand for culinary and medicinal uses, that drove European expeditions in search for new maritime routes to reach the east. In the 15th century, spices came to Europe via Southwest Asia, a region Europeans referred to as the “Middle East.” Seeking to maximize profits, Europeans set sail to establish new routes and gain direct access to Asia’s spices and other valuable commodities. Columbus landed in the Americas, believing he had arrived in India and labeling the locals “Indians,” while Vasco da Gama sailed around African Cape of Good Hope, up the coast of East Africa, and across the Indian Ocean, ultimately reaching India in 1498.

From 1500 onwards, European powers pursued control of the spice trade and the ports and territories that involved it. Lacking desirable trade goods, they became pirates in the Indian Ocean, looting seafaring merchants and eventually leveraging their cannon ships and weapons to seize the spice trade by force, through colonization. The Portuguese were the pioneers of colonization in the Indian Subcontinent, establishing their first colony in the Malabar Coast, an established center of valuable goods (spices) and crafts (shipbuilding) discussed earlier. Established in 1510, Goa remained a colony of Portugal for 450 years, one of the longest held colonial possessions in the world. This colonial legacy can be noted by many of Goa’s historic buildings and cathedrals.

British Colonization

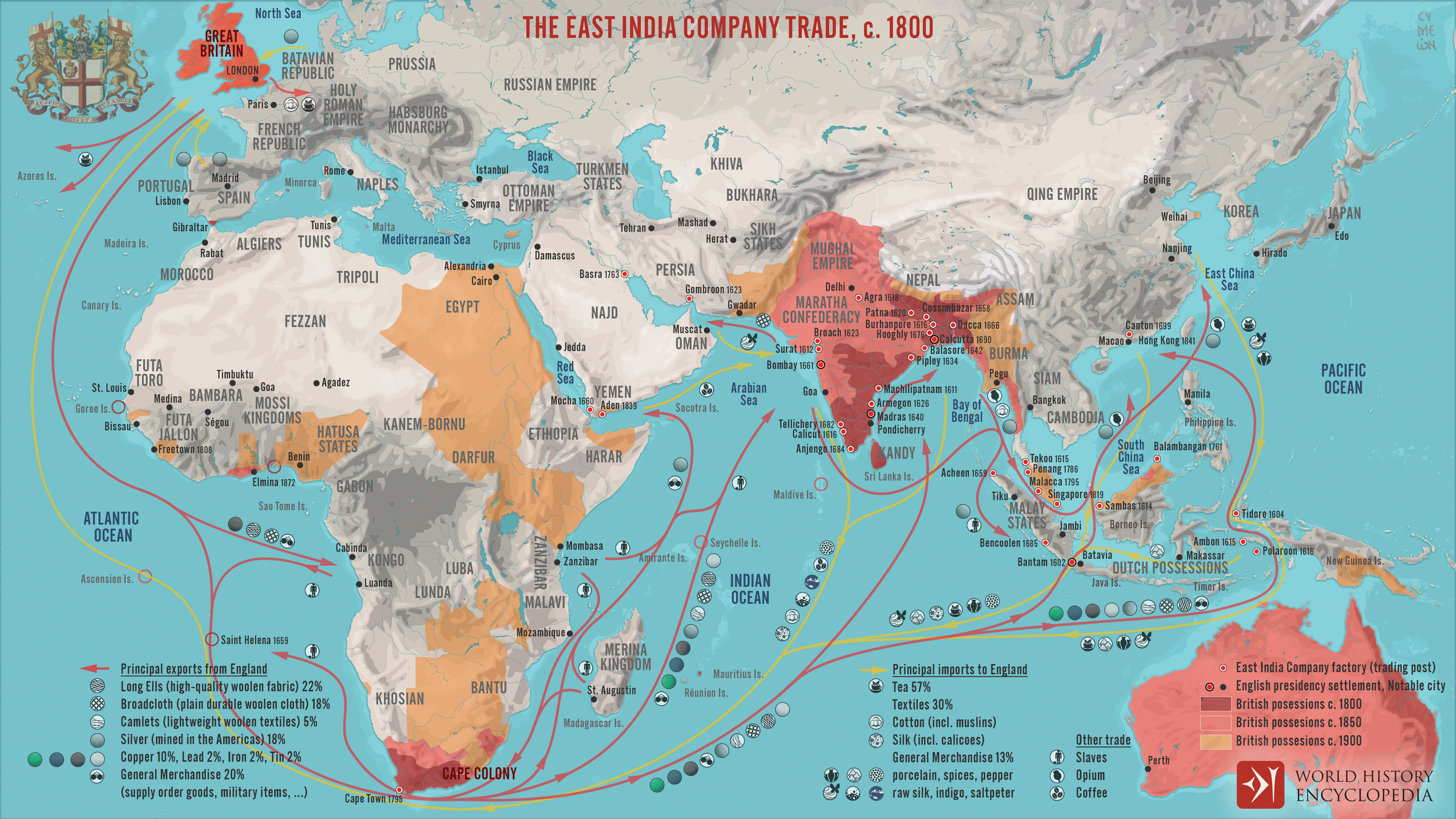

The British eventually displaced other European powers and established their dominance in South Asia, starting in 1600 when Queen Elizabeth established the East India Company (EIC). Before the EIC, the British bought goods from India like everyone else, by trading with native merchants and intermediaries. The chartering of the EIC, however, granted a few hundred British merchants with exclusive right on all trade, effectively monopolizing the trade of highly desirable and profitable commodities, primarily spices, but also silk, opium, indigo, and tea. Backed by the British Empire, the EIC evolved into a brutal colonial power, eventually employing a massive private army to seize and tax vast territories in the Indian subcontinent.[6] By 1800, the company’s domain extended from many trading ports along the Indian coast to as far north as the Delhi, the capital of the Mughal Empire the EIC replaced (see map).

In 1857, however, Indian soldiers working for the EIC’s army, known as sepoys, revolted against the rule of the EIC. Known as the Sepoy Rebellion, the revolt united Muslim, Sikh, and Hindu soldiers against the British, igniting a wider unified first war for independence. The uprisings motivated the British Empire to suppress rebellions with military force and to bolster its control, replacing the EIC to rule South Asia as a colony.

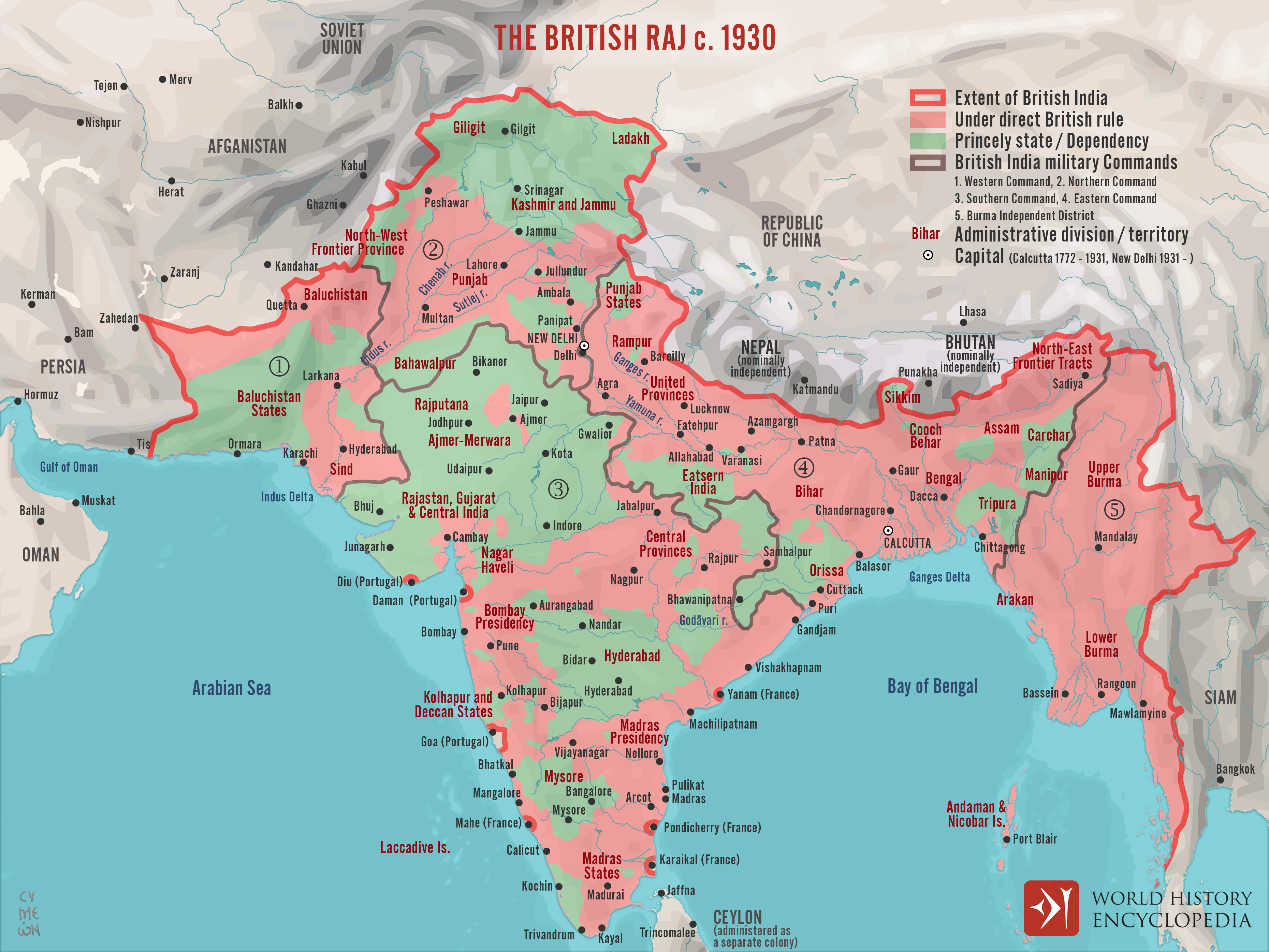

The British Raj, or British colonial rule, directly controlled as much as two thirds of the Indian Subcontinent. The remaining territories continued as princely states, territories that remained under the ordinance of local rulers. The British were intentional about calling these rulers “princes,” not “kings,” and their territories “princely states,” not “kingdoms” – a reminder that the British monarch was supreme. Princely states were ruled indirectly, as the British maintained control through subsidy treaties. These treaties entailed annual payments to the British crown in exchange for British military support and protection. While these arrangements allowed princes a degree of sovereignty on internal matters, the British maintained the economic benefits of collecting payments and controlling international affairs. It was part of a “divide and rule” strategy for consolidating dominion of the region by leveraging a native governing elite and exploiting internal divisions.[7]

The Partition: A Bittersweet Independence

India had always been the pride and prize of the British Empire – an imperial treasure chest and model of colonial rule. Yet, by the early 20th century Indians increasingly sought after an independent India. For decades a grass-roots movement led by Mohandas Gandhi and two political parties, the Indian National Congress and Muslim League, had petitioned, protested, and boycotted against colonial rule. World War II proved to be the tipping point, as by the end of the war in 1945, British rule in India seemed irreparably damaged. In addition to the continuing independence movement, the wartime Bengal famine (1943) had shown British officials woefully inept in managing the country. With Britain bankrupt and open unrest amongst British troops in India, few believed Britain had the strength or moral right to rule India anymore.

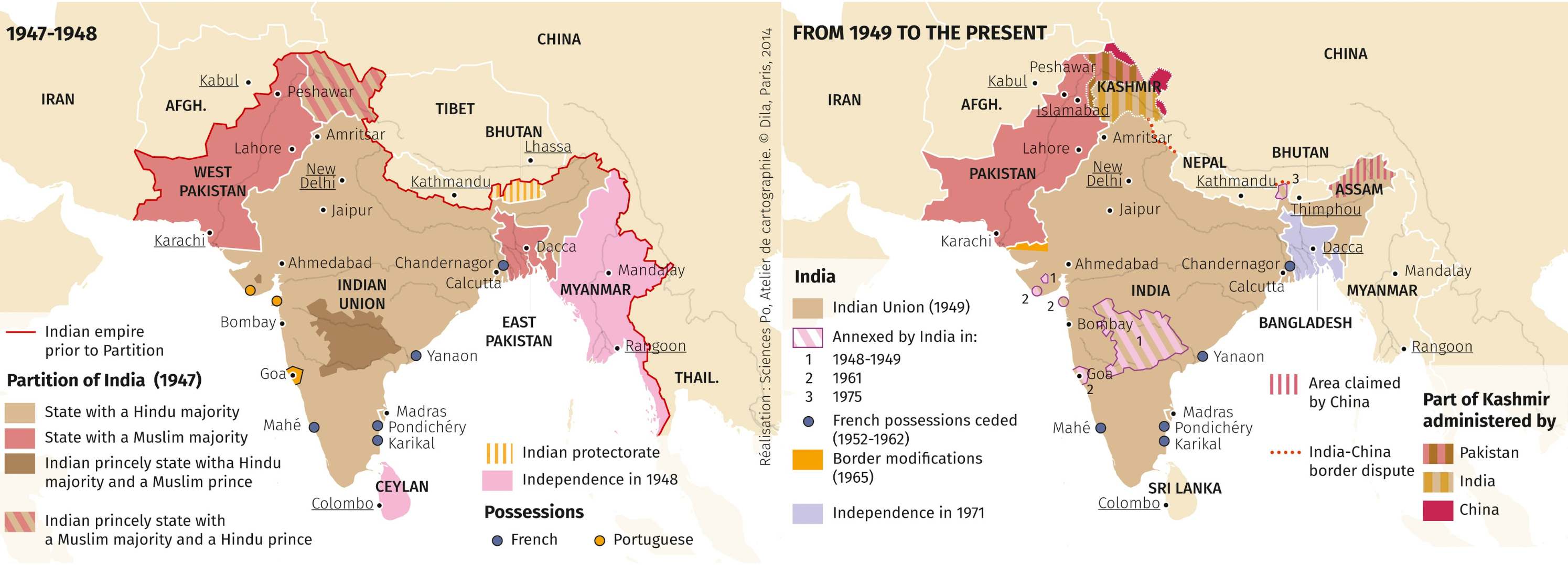

In 1946, British officials were ready to negotiate India’s independence. After elections were held across the country, Indian politicians joined the British to write India’s first constitution. The two major Indian political parties, however, were unable to compromise on what a united independent India should be. The Indian National Congress led by Gandhi’s ally Jawaharal Nehru insisted India must stay united and have a strong central state. By contrast, the head of the Muslim League Mohammad Ali Jinnah would only agree to a partition, or physical separation into separate states. For centuries Hindus and Muslims had lived side by side across the subcontinent. Yet with the arrival of mass democracy and independence, Jinnah and the Muslim League feared Muslims, as the smaller population, would be perpetually sidelined in a Hindu-majority India. Dividing India into separate Hindu and Muslim states would guarantee Muslims could determine their own future.

With no compromise found, the political tensions filtered down to the local level. Riots broke out between Hindus and Muslims in the northeast provinces and support for partition grew stronger. Gandhi’s pleas for unity and tolerance fell on deaf ears and he vowed to starve himself until the violence stopped. While Gandhi’s threat worked, as the bloodletting came to a pause, a sullen mood hung over the country. With law and order breaking down and colonial authority fading, the British took decisive action. They accelerated their withdrawal plan and brokered an end to the deadlock between Nehru and Jinnah, with Nehru and Indian National Congress agreeing to partition; a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan it would be. When independence arrived for two whole days, August 14-15, 1947, exuberant crowds and euphoria swept across the land as the old British Raj became two new countries: India and Pakistan.

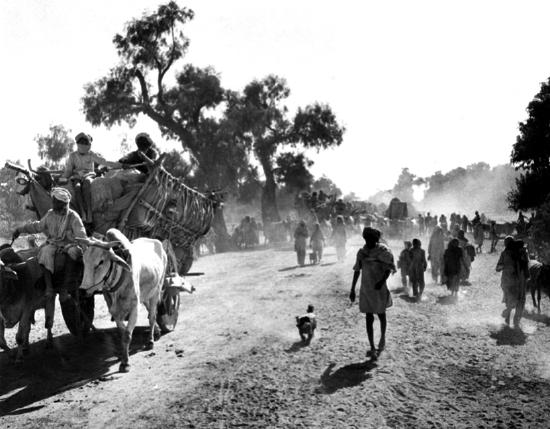

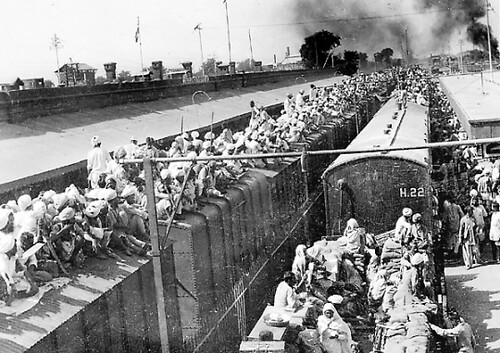

Independence proved bittersweet. Even before the celebrations began, communal violence exploded along the still unclear borders. Communities that had co-existed for almost a millennium became enemies overnight, attacking one another in a wave of immense violence. When the borders were declared, a tidal wave of refugees took to dirt roads by foot or crammed onto overflowing railroad trains going in opposite directions in one of the largest migrations of human history; Hindus fleeing Pakistan to India and Muslims fleeing from India to Pakistan. By 1948, two million people died, including Gandhi by political assassination, and some 15 million people abandoned their homes never to return. It was a defining moment for 20th Century South Asia, one that is still influences how South Asians recollect the past and envision the future.[8]

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): These two maps present the British partition of the following the Indian Independence Act of 1947 and the subsequent redrawing of state boundary lines from 1949 to the present day. The redrawing of boundaries are a result of many factors, including the factionalization of religious groups under divisive tactics employed by the British Empire (Copyright; Espace Mundial l'Atlas, permitted use).

While the voracious nature of British colonization is well documented and hard to contest, some contend that British colonization in the Indian subcontinent provided the region with some lasting benefits Indians enjoy until this day. The rationale follows that prior to colonization a unified India did not exist, and that it was the British that brought India together into a cohesive unit of governance, connected through a system of railroads and a common language (English). The notion that colonizers have bestowed gifts onto colonized peoples is more pervasive than many realize: A 2020 poll on British opinion reports that about one-third of Britons believe that the British Empire is a source of pride and that former British colonies are better off from having been colonized by Britain.[9]

This narrative promoting the most pervasive colonizer in human history as a benevolent force demands critical reflection. Shashi Tharoor, an Indian public intellectual and diplomat, vigorously challenged such interpretations of history in Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India (2017). The book provides a historical exploration that contests romanticized notions about British colonization, explaining that the British were not benevolent rulers who left “gifts” for India. Instead, the author details how British colonization plundered a great civilization, leaving behind a centuries-long legacy of exploitation and fragmentation.

For one, Tharoor argues that the British Empire did not unify India. As described in the opening of this chapter, the notion of a geographical entity in the subcontinent is well encrypted in Sanskrit texts describing a land among sacred rivers that has existed for thousands of years. Precolonial India was a civilizational space where diverse cultural groups with many overlapping cultural practices coexisted. Instead of acting as a unifying force, the British focused on sharpening, even constructing, class and religious divisions to impose their control. One of the first examples of this “divide and rule” strategy was the first national census (1872) that classified Indians based on religion, caste, or tribes according to British assumptions about Indian society. The census served to legitimize and accentuate differences among groups, a strategy used to prevent unity against British rule which was construed as necessary to maintain political coherence and peace. English teaching and learning, too, was solely conducted to create a “class of interpreters” to facilitate British rule. The British had no intentions of expanding education to the masses.

The extensive Indian railway system, often touted as a lasting benefit from colonization, was a colonial venture funded by the Indian people who paid high taxes to return exorbitant profits for British “investments” in their construction. Yet, the Indian-funded railway infrastructure was primarily designed to serve the needs of the Indian people but to facilitate the export of natural resources to Britain. Among these was the exports of rice that effectively diverted food from hungry masses during devastating famines that claimed millions of Indian lives. To make matters worse, the entire industry – from the manufacturing of trains to the employment of technicians and conductors – was highly exclusive of Indians and its profits channeled to Britons.

The cementing of religious divisions and the leveraging of the English language and railways are only a few among many of the examples that Tharoor provides of how the British never intended to benefit Indians with their tools of conquest. The fact that Indians have leveraged the English language, railways, or any vestige of colonialism for their own liberation and economic gain, Tharoor argues, is to the credit of Indians, rather than the benevolence of the British. Contrary to the imagination of many Britons, the Indian subcontinent had thrived without the British. Their fabled wealth lured Europeans to venture across the seas into the unknown. Far from being peripheral or poor, the Indian subcontinent constituted a much larger share of the global economy than Britain, as it was an epicenter of resources, production, and trade.[10] In other words, the rise of Britain was predicated upon the appropriation of India’s wealth, a wealth accumulation by dispossession estimated at trillions of dollars.[11]

Considering the critical reflections presented in Tharoor’s book opens an opportunity to replace apologetic narratives about “gifts from colonizers” with a recognition of the substantial and long-lasting cultural and economic harm experienced by colonized peoples in India and elsewhere.

References:

[1] Green, A. S. (2021). Killing the priest-king: Addressing egalitarianism in the Indus civilization. Journal of archaeological research, 29(2), 153-202.

[2] Smithsonian National Museum of African Art showcases a digital exhibition, Sailors and Daugters: Early Photography and the Indian Ocean.

[3] One of the most detailed record of the ancient trade network of the Indian Ocean is the book Periplous of the Erythrean Sea, published in the 1st Century AD by an unknown Greek author. This map depicts the trade routes and goods described in this record.

[4] Mathew, K. S. (2017). Shipbuilding, navigation and the Portuguese in pre-modern India. Routledge.

[5] Tharoor, S. (2018). Inglorious empire: What the British did to India. Penguin UK.

[6] Dalrymple, W. (March 4, 2015). The East India Company: The original corporate raiders. The Guardian.

[7] Rahman, A., Ali, M., & Kahn, S. (2018). The British art of colonialism in India: Subjugation and division. Peace and Conflict Studies, 25(1), 5.

[8] Dalrymple, W. (June 22, 2015). The Great Divide. The New Yorker Magazine.

[9] Smith, M. (March 11, 2020). How unique are British attitudes to empire? You Gov, UK.

[10] From 1600-1940, as quantified in Tharoor, S. (March 8, 2017). ‘But what about the railways…?’ The myth of Britain’s gifts to India. The Guardian.

[11] Hickel, J. (Dec 19, 2018). How Britain stole $45 trillion from India. And lied about it. Al Jazeera. Based on the works of Nielsen, K. B. (2020). Agrarian and Other Histories: Essays for Binay Bhushan Chaudhuri: Shubhra Chakrabarti and Utsa Patnaik (eds)(New Delhi: Tulika Books, 2017).

Attributions:

“Indus Civilization" is adapted from Green, A. S. (2021). Killing the priest-king: Addressing egalitarianism in the Indus civilization. Journal of archeological research, 29(2), 153-202. CC BY 4.0; and Mark, J. (Oct 7, 2020). Indus Valley Civilization. World History Encyclopedia, CC BY NC SA 4.0.

"Mughal Empire" is adapted from Netchev, S. (2022). Mughal India. World History Encyclopedia, CC BY NC SA 4.0.

“Colonization” is adapted from Cartwright, M. (June 9, 2021). The spice trade & the age of exploration. World History Encyclopedia, CC BY NC SA 4.0; and Cartwright, M. (October 31, 2022). Indian Princely States, CC BY NC SA 4.0.

“A Traumatic Independence” is adapted from New Nations of Asia, CC BY NC SA 4.0.

This page contains adaptations from “Patterns of Human Settlement in South Asia” by Caitlin Finalyson, CC BY NC SA 4.0; and “Introducing the Realm” by the University of Minnesota. CC BY NC SA 4.0.