14.3: Phonological change

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 194110

- Catherine Anderson, Bronwyn Bjorkman, Derek Denis, Julianne Doner, Margaret Grant, Nathan Sanders, and Ai Taniguchi

- eCampusOntario

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Many of the phonological changes we find diachronically are the same phonological processes that we find synchronically (see Section 4.9 for spoken languages and Section 4.10 for signed languages). A few additional types are discussed in the section.

Sporadic phonological change

One type of sporadic phonological change is metathesis, in which parts of the pronunciation swap positions with each other. For example, the ASL sign for DEAF1 touches near the ear first and then near the mouth, but there is a metathesized version DEAF2 that swaps the locations, touching near the mouth first and then near the ear.

DEAF1: https://www.signingsavvy.com/media2/mp4-ld/23/23017.mp4

DEAF2: https://www.signingsavvy.com/media2/mp4-ld/23/23016.mp4

Other signs can have metathesis in ASL, such as HEAD and RESTAURANT, but since this is a sporadic change, it only affects a few signs, so there are many more signs that do not normally have metathesis, such as CHILDREN and THING (Liddell and Johnson 1989):

HEAD1: https://www.signingsavvy.com/media2/mp4-ld/30/30884.mp4

HEAD2: https://www.signingsavvy.com/media2/mp4-ld/30/30885.mp4

RESTAURANT1: https://www.signingsavvy.com/media2/mp4-ld/22/22673.mp4

RESTAURANT2: https://www.signingsavvy.com/media2/mp4-ld/22/22674.mp4

CHILDREN: https://www.signingsavvy.com/media2/mp4-ld/21/21593.mp4

THING: https://www.signingsavvy.com/media2/mp4-ld/29/29617.mp4

Metathesis also happens in spoken languages, where it affects the position of phones. For example, the English word ask has undergone metathesis multiple times in its history. In Old English, we find it first attested as ascian with [sk], but we soon find evidence of a metathesized form axian or acsian with [ks]. Both versions persisted in various regions, but axian was dominant enough throughout Old English that it resisted a different Old English sound change, [sk] > [ʃ], which we see evidence for in words like the following:

- bishop < bisceop

- fish < fisc

- shine < scīnan

- wash < wascan

If the original ascian had been stable through Old English, it should now be pronounced like ash in Modern English due to the [sk] > [ʃ] sound change. Any word now with [sk] must have gotten its [sk] by avoiding this sound change somehow. In the case of words like skip and whisk, they were borrowed later in Old English, after the [sk] > [ʃ] change was complete. In the case of ask, the axian variant was dominant while [sk] was changing, so axian was unaffected, like many other [ks] words:

- axle < eaxl

- axe < æx

- vixen < fyxen

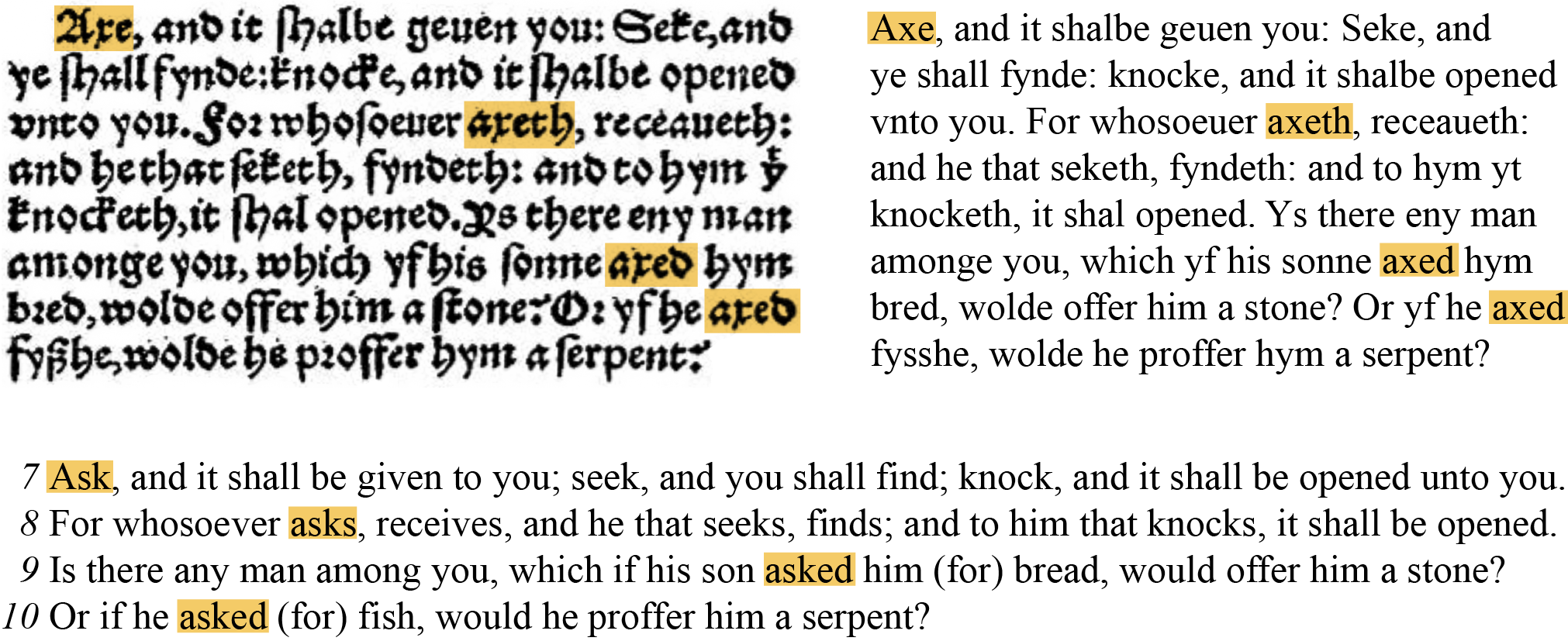

The [ks] variant stayed dominant through Middle English and into Early Modern English. For example, it can be found multiple times in in the Coverdale Bible, the first complete version in English, published in 1535. See Figure 14.4 for sample text from Matthew 7:7–10 with four instances of the [ks] variant.

Some time later, metathesis happened again, and we now have [æsk] for many English users today. However, [æks] has persisted in many dialects due to its long history in English. In many cases of such long-standing variation, we often accept the difference: many Canadians say [əˈlumənm̩] aluminum and [ˈvaɪtəmn̩] vitamin, while many Brits say [ˌæljəˈmɪnim̩] aluminium and [ˈvɪtəmn̩]; many Canadians say [ˈædl̩t] adult, while many Americans say [əˈdʌlt]; etc. These differences are usually no more than points of curiosity and polite joking.

But with [æsk] versus [æks], we find intense dislike and outright vitriol. People who use [æks] are often ridiculed as unintelligent, uneducated, and unworthy of respect. A key factor is that [æks] is popularly associated with African American English (although it is used in many other dialects), so expressing disdain for the people who use [æks] is a way to covertly express racial prejudice through linguistic prejudice.

But the linguistic prejudice is just a convenient mask. No one expresses as much hate towards metathesis in general; everyone ignores wasp and bird, which are metathesized from Old English wæpse and bridd. No one expresses as much hate for similarly small differences between dialects, such as alumin(i)um or adult. However, because this particular metathesized word happens to be associated with African American English, the hatred more readily comes out. Given the issues of language and power that we have touched on throughout this book, especially in Chapter 2, this unfortunate outcome is unsurprising.

Sporadic sound change

A language change that affects the phonology of a spoken language specifically is known as a sound change. One type of sporadic sound change is a spelling pronunciation, which is where the pronunciation of a word shifts to better match its spelling. This happens in English because the connection between spelling and pronunciation is often inconsistent (see Section 3.6), so a spelling pronunciation can help reduce this inconsistency.

For example, the English word Arctic was originally borrowed into Late Middle English from Middle French artique, which itself is derived from Latin arcticus. The spelling was changed a few hundred years later, with a <c> added based on the Latin spelling, which eventually caused the pronunciation to shift to [ɑrktɪk]. Other examples of spelling pronunciation in English include the following:

- the [l] in falcon (borrowed from Old French faucon, then respelled to match Latin falcōnem)

- the [h] in hectic (Old French etique, Latin hecticus)

- the [k] in perfect (Old French parfit, Latin perfectus)

Interestingly, many people today still pronounce Arctic as [ɑrtɪk], closer to the original Middle English pronunciation, though this pronunciation is often stigmatized and is frequently found on lists of “commonly mispronounced words”. However, this attitude directly contradicts a common belief among language pedants that language change “ruins” language. If change itself is stigmatized, then older forms should always be more prestigious. However, with Arctic, it is the newer pronunciation [ɑrktɪk] that is prestigious, because of its spelling.

Of course, spelling pronunciations are not always prestigious either. Pronouncing the [h] in honest would likely be ridiculed, not prestigious. So neither history not spelling are reliable guides to a prestigious pronunciation. In fact, there is no consistent linguistic factor that correlates to prestige. Some prestigious forms are older, some are newer; some are pronounced to match their spelling, some are not. What is consistent across prestigious forms is that they are used by those who hold social power (see Chapter 2 for more discussion).

A different type of sporadic sound change involves stereotypes about the pronunciation of words in other languages, and using those stereotypes rather than the original pronunciation. This is known as hyperforeignism. There are many examples of hyperforeignism in English, such as the following:

- The capital of China is called Beijing in English, which is borrowed from Chinese 北京 (Běijīng). The Mandarin pronunciation is [pèɪ.t͡ɕíŋ], which is very similar to a possible English pronunciation [bed͡ʒɪŋ]. However, many English speakers use the hyperforeignism [beʒɪŋ] instead, because [ʒ] is relatively rare in English but does occur in many borrowings (azure, Dijon, genre, etc.), so it reinforces the foreignness of Beijing as a city in another country.

- The word lingerie was borrowed from French, where the final vowel is pronounced [i]. However, many French borrowings have a final [e] sound (ballet, chez, fiancé, etc.), so the pronunciation of lingerie was changed in English to match this stereotype by replacing final [i] with hyperforeign [e].

- Another stereotype about French is that where English might have a final [s], French does not. We see this in many borrowings from French into English, where the word looks like it should be pronounced with final [s]: chassis, foie gras, rendezvous, etc. However, French does allow final [s], as in the expression coup de grâce [ku də ɡʁɑs], but in the borrowed form in English, we drop the final [s] so that it seems more French-like, resulting in the hyperforeignism [ku də ɡrɑ].

There are many other types of sporadic sound changes, too many to go into detail here. Here a three more types, with brief summaries and examples:

- dissimilation: when a phone shifts to avoid being to similar to a nearby phone; for example, despite the spelling, governor is often pronounced [ɡʌvənr̩], so that the first <r> is not pronounced in order to dissimilate from the second, leaving only one [r] in the word (note that the first [r] is still pronounced in the base verb govern)

- analogy: when a word shifts to match a pattern found in other words, especially from a rare pattern to a more common pattern; for example, nuclear has a very rare [-klir̩] sequence that many people pronounce by analogy as the more common sequence [-kjəlr̩], as in binocular, circular, molecular, muscular, particular, etc. (see more discussion and examples in Section 14.4)

- immediate model: a special type of analogy where a word shifts by analogy to match another word that it is frequently used together with, especially in an established sequence; for example, February is normally pronounced [fɛbjəwɛri] rather than [fɛbruɛri], by immediate model with [d͡ʒænjəwɛri] January, since the two words are often said together in sequence

Regular phonological change

So far, we have looked mostly at sporadic changes, which affect only a limited number of words. However, a phonological change can be regular instead, which means that it applies uniformly in a consistent environment across every word possible, similar to how synchronic phonological rules apply. For example, if the [sk] > [ks] metathesis had been regular in Old English rather than sporadic, then every word with [sk] would have changed, not just ascian.

Modality seems to affect the potential for regularity in phonological change. Spoken languages can have both regular and sporadic sound changes, while signed languages seem to undergo only sporadic phonological changes. This is likely for the same reasons that signed languages do not seem to have productive phonological rules, but it could instead be due to our lack of understanding of the phonology of signed languages (see Section 4.10 for discussion). Thus, we focus on regular sound changes here.

The idea of that sound change could be regular was theorized in the late 1800s. Prior to that, historical linguists primarily focused on describing observed changes in the written record of known languages. However, a group of German linguists known as the Neogrammarians proposed that all sound changes were regular, not sporadic. So if a change existed, it had to affect every word it could; exceptions must be due to borrowing or some other separate process. This proposal is known as the regularity principle or the Neogrammarian hypothesis.

We now know that the regularity principle is not fully true. As discussed earlier in this section, many sound changes are sporadic. But even for those that are regular, they may spread slowly through the lexicon, word by word or morpheme by morpheme, typically affecting higher frequency words first, through a process called lexical diffusion (Wang 1969, Chen 1972, Chen and Wang 1975; see also Schuchardt 1885 for early recognition of this phenomenon). This means at any given moment, we may see only a partial effect of a sound change, affecting some words but not others.

For example, in Philadelphia, words like bad, glad, and mad have a tense [æ̝] due to a sound change affecting /æ/ before /d/. However, there are lots of other words in the lexicon, such as dad and sad, that still have lax [æ] because the sound change has not diffused to them yet (Labov 1981).

However, despite the flaws of the regularity principle, it was crucial for the development of the field of historical linguistics, as it turned from pure description to a predictive science (see Appendix 2.3 for discussion). The regularity principle is the core tool used in Sections 14.8–14.11 for helping us understand and make reasonable hypotheses about the linguistic past.

Conditioning of regular sound change

Like synchronic phonological rules, a regular sound change may be conditioned, which means that it only happens in a specific set of environments, such as at the end of the word or between vowels. For example, by Middle English, [sw] clusters were pronounced as [s], but only before back vowels. So sword and answer (from Old English andswaru) now have [s] because of the following back vowel, while sweet, swift, and swell all retained their original [sw] because the following front vowel blocked this change from applying.

We can notate such conditioned sound changes similarly to how we notated phonological rules in Section 4.7, using the symbols / and ▁ to specify the environment, but using > instead of →→ to represent that this is a diachronic sound change rather than a synchronic phonological rule. The conditioned change of [sw] to [s] change could thus be represented as follows:

- [sw] > [s] / ▁ back vowel

Some regular sound changes are instead unconditioned, which means they occur everywhere, regardless of the environment. For example, Old English had a high front round vowel [y] that changed to [i] everywhere in Middle English, as in brycɡ > bridge and cyssen > kiss (compare the German cognates Brücke and küssen, which still have a high front round vowel). This unconditioned change would be notated as [y] > [i], with no environment.

Phonemic effects of regular sound change

Sound changes can also be classified by whether they affect the number of phonemes in a language. If a regular sound change decreases the number of phonemes in a language, it is called a phonemic merger or simply merger. The [y] > [i] change was a merger, since /y/ and /i/ were separate phonemes before the merger. We can highlight the phonemic nature of this change by using slashes instead of square brackets: /y/ > /i/. In addition, mergers are sometimes notated with both of the older phonemes on one side, as in /i, y/ > /i/, to highlight that this was a merger.

When we acquire a language, we do not acquire its history, so once two phonemes have merged, there is no longer any way to reliably distinguish them. Thus, when a child acquires kiss and miss now, they cannot know that 1000 years ago, kiss used to be pronounced with [y] and miss with [i]. The merger has caused these two words to be perfect rhymes in Modern English, even though they used to be pronounced with different vowels in Old English (cyssen with [y] and missan with [i]).

Other changes can increase the number of phonemes. This is called a phonemic split or just split. An example of a split is the emergence of voiced fricatives as phonemes during Middle English. Old English only had voiceless fricatives as phonemes, but these already had voiced allophones between vowels. For example, cnif ‘knife’ was pronounced [kniːf], but its plural cnifas was pronounced [kniːvas], and we still have the [v] in the plural in Modern English knives. But [f] and [v] were allophones of a single phoneme /f/, until English borrowed a lot of Old French words that had [v] in a position where it was in contrast with [f], as with fine and wine. As discussed in Chapter 4, once there is contrastive distribution and the potential for minimal pairs, the phones belong to separate phonemes, which meant a new phoneme /v/ came into existence in Middle English.

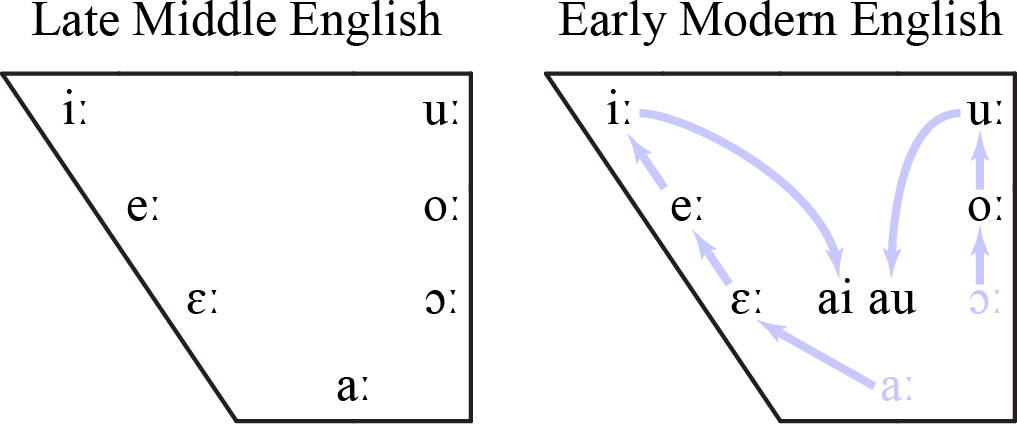

A sound change may also keep the number of phonemes constant, only changing their pronunciation. This is known as non-phonemic shift or just shift. There have been a number of such shifts in the vowel system throughout the history of English. In particular, Late Middle English had four short vowels, [i], [e], [o], and [u], that shifted in pronunciation into Early Modern English by becoming lax, plus an fifth short vowel [a] that did not change (see Figure 14.5). Since there were no pre-existing lax vowels, these shifts resulted in no mergers, so there was no change in the number of vowels.

In this case, the different shifts did not interact with each other, but it is possible for shifts to overlap. This happened with the Middle English long vowels in a shift known as the Great Vowel Shift, which is one of the major features marking the transition from Middle English to Modern English (see Section 14.1).

The Great Vowel Shift in English

In addition to the five short vowels discussed earlier, Late Middle English also five long vowels that matched the short vowels in vowel quality, [iː], [eː], [aː], [oː], and [uː], plus two other long vowels that did not have a matching short vowel, [ɛː] and [ɔː]. During the Great Vowel Shift, the long vowels changed in pronunciation separately from the short vowels, so that the long-short pairs ended up differing in both length and vowel quality.

In addition, the long vowels shifted in such a way that their shifts overlapped with each other. For example, [aː] shifted to [ɛː], while [ɛː] shifted to [eː]. Crucially, there was no merger: [aː] and [ɛː] each shifted separately by one step. This kind of overlapping series of non-merging shifts is a called a chain shift. In a chain shift, there are at least two changes, with the newer form of one change being the older form of some other separate change. In this case, the “link” in the chain is [ɛː], which is the newer form of the [aː] > [ɛː] change and the older form of the [ɛː] > [eː] change.

This chain was actually longer, because of two additional changes: [eː] > [iː] and [iː] > [ai]. The back vowels had a similar chain shift, with [ɔː] > [oː], [oː] > [uː], and [uː] > [au]. Thus, the Great Vowel Shift consisted of two chain shifts, one involving four vowels and one involving three vowels (Figure 14.6).

There are a few ways that a chain shift could happen, depending on when the individual shifts occurred in time with respect to each other. This ordering of separate changes is called their relative chronology. One option is that all the shifts happened more or less simultaneously, so that [aː] shifted up at the same time that [ɛː] did, which was the same time that [eː] did, and so on.

However, it is more likely that some shifts happened a bit earlier than others. If the high vowels became diphthongs first, this would have left a gap in the vowel space. In general, languages tend to have their vowels evenly distributed throughout the vowel space, so this gap would pull the lower vowels up to keep the spacing more even. This is called a pull chain.

Instead, the lower vowels at the other end of the chain might have started shifting first, with [aː] and [ɔː] raising toward [ɛː] and [oː]. This would crowd that part of the vowel space vowels, and to avoid a merger, [ɛː] and [oː] would shift higher as well. This would create a chain reaction of each vowel pushing the next vowel up and out of the way, until the high vowels have nowhere to go, so they become diphthongs. This is called a push chain.

Based on written evidence, it seems like the Great Vowel Shift may have in fact been a bit of a mixture of push and pull chains, with the tense high vowels [eː] and [oː] shifting first. This would push the high vowels [iː] and [uː] while also pulling the lower mid vowels [ɛː] and [ɔː] to fill the gap. All three possibilities are visualized in Figure 14.7.

There were some further changes that affected most of these vowels later in Modern English to give us the vowels we have today (for example, [ɛː] and [eː] merged to [e]), but the changes for the long vowels discussed above are the essence of the Great Vowel Shift.

Interestingly, German underwent a similar vowel shift, but it did so much earlier than English, before there was widespread printing to standardize the spelling. We can see this in cognates like German bei ‘by’ and English by, which are both now pronounced [baɪ] but originally had [iː] prior to their vowel shifts. German shifted [iː] to a diphthong very early, and then sometime later, printing came along, which helped standardize spelling in both languages to match the pronunciation at the time. For German, this was <bei>, while English retained <by>, because this word still had [iː]. Finally, after the spelling had been settled, the Great Vowel Shift occurred in English, and the pronunciation of by changed in the same way it had for German bei, but the English spelling was not updated to reflect to new pronunciation.

We see further evidence of the Great Vowel Shift in the morphology of English. In Middle English, allomorphs could differ in length in predictable ways, so that one allomorph of a morpheme had a long vowel in some environments, while another had a short vowel in other environments. Since the two types of vowels shifted differently due to the Great Vowel Shift, the pronunciation of the relevant allomorphs shifted differently as well. We can see remnants of this older long-short pattern preserved in word pairs like the following:

- divine–divinity, hide-hid, etc., with [aɪ]-[ɪ] < [iː]-[i]

- serene-serenity, thief-theft, etc., with [i]-[ɛ] < [eː]-[e]

- graze-grass, sane-sanity, etc., with [e]-[æ] < [aː]-[a]

- goose-gosling, school-scholarly, etc. with [u]-[ɒ] < [oː]-[o]

- house-husband, pronounce-pronunciation, etc. with [aʊ]-[ʌ] < [uː]-[u]

The result is a lot of seemingly arbitrary complexity in the phonology and morphology of English. As discussed in Section 14.4, there are ways that languages change that can help reduce this complexity.

Check your understanding

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

References

Chen, Matthew Y. 1972. The time dimension: Contribution toward a theory of sound change. Foundations of Language 8(4): 457–498.

Chen, Matthew Y., and William S-Y. Wang. 1975. Sound change: Actuation and implementation. Language 51(2): 255–281.

Coverdale, Myles (trans.) 1535. Biblia. The Bible, that is, the holy Scripture of the Olde and New Testament, faithfully and truly translated out of Douche and Latyn in to Englishe. Antwerp: Merten de Keyser.

Labov, William. 1981. Resolving the Neogrammarian controversy. Language 57(2): 267–308.

Liddell, Scott K., and Robert E. Johnson. 1989. American Sign Language: The phonological base. Sign Language Studies 64 (Fall): 195–278.

Nyberg, Henrik Samuel. 1974. A manual of Pahlavi. Part II: Ideograms, glossary, abbreviations, index, grammatical survey, corrigenda to Part I. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

Schuchardt, Hugo. 1885. Ueber die Lautgesetze. Gegen die Junggrammatiker. Berlin: Oppenheim.

Wang, William S-Y. 1969. Competing changes as a cause of residue. Language 45(1): 9–25.