3.1: Introduction to States

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 135834

- Dino Bozonelos, Julia Wendt, Charlotte Lee, Jessica Scarffe, Masahiro Omae, Josh Franco, Byran Martin, & Stefan Veldhuis

- Victor Valley College, Berkeley City College, Allan Hancock College, San Diego City College, Cuyamaca College, Houston Community College, and Long Beach City College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define, and distinguish between, key terms including state, regime, and nation.

- Recall the development of the state from its origins.

- Identify common characteristics of modern states.

- Consider the implications of political capacity in various states.

Introduction

What is government? Is government necessary? Why do governments exist?

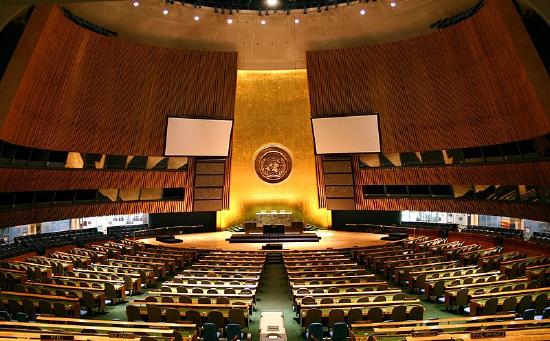

At some point in your life, you may have asked some of these questions. Many times, the fact that people live under a government or in a country that has rules and societal norms, can be difficult to grasp. At the present moment, there are almost 8 billion people on the planet and almost 200 identified countries worldwide. There are 193 member countries in the United Nations. The fact stands that of the nearly 8 billion people currently on the planet, most live under some kind of government or are affiliated with one of 200 countries on the planet. This means that most human beings on this planet have found themselves in the situation of being ruled over or governed, and while daily life is filled with a myriad of basic to-do lists and activities, many of the activities of humans on the planet are, in small and big ways, dictated by political powers. To this end, this chapter considers important aspects of political power within countries, the important terminology we use in the field of comparative politics to understand the world around us, and important problems and issues related to states and regimes.

The Social Contract and Social Order

Let’s begin with some critical questions: Why does government exist? Is government necessary?

A society without government or central leadership is one that lives in anarchy. Anarchy is defined as a lack of societal structure and order where there is no established hierarchy of power. Many scholars and political scientists have considered, at great length, the phenomenon and applicability of anarchy, though anarchy has not been a norm within the communities of humans living over the past 15,000 years. Even prior to the establishment of formal governments and formalized institutions, human beings were organizing themselves for various reasons. One of the first things that compelled human beings to organize themselves was the pursuit of survival. Over the course of human history, humans began to understand that survival seemed more feasible when they cooperated with one another. While they didn’t have established, written laws, early humans did begin to have informal rules and norms for how they handled themselves in society. In some cases, informal leaders also existed and helped guide how humans were supposed to act in order to survive.

Early humans often existed as small groups composed mostly of family members. For example, think of your own family. Are there certain rules your family followed while you were growing up? Who was in charge? Who told you what to do and when to do it? Consider this, and consider how the existence or non-existence of rules in your family contributed to how your family worked and lived. Did rules help your family? Did you think the leaders, parental guardians, in your family were legitimate? Did you follow their rules? In time, families banded together into tribes, which in turn, formed their own rules and norms for how their group should act, usually with the common goal of surviving. Also, in time, circumstances changed for humans, particularly in terms of how they were able to survive. Initially, there was a hunter-gatherer approach, where humans hunted for their food and gathered fruits, berries and other available plant life in order to survive.

About twelve thousand years ago, society was able to shift its approach. Humans found a way to stay in one place for longer through the agricultural revolution. Humans were now able to till the land for crops and begin early irrigation methods to enable the watering of their crops. With the ability to stay in one place for longer, rather than moving around constantly to hunt and gather, human groups began to aggregate in common locations. The agricultural revolution also led to human population growth. This population growth, combined with more people living closer together, also led to the need for formal societal organization. Humans, now living closer to each other, were to forced to develop some sort of order to ensure survival. In looking back on this period of human history, the main takeaway is that humans chose not to live in anarchy instead of a living in a chaotic world without rules. Humans calculated that their status quo would be improved with a strong set of rules. In addition, both individual and societal goals could be accomplished through mutual cooperation in a rules-based society. Out of this, would come what Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Rousseau called the social contract.

A social contract is defined as either a formal or informal agreement between the rulers and those ruled in a society. Those who are ruled submit to the laws of the rulers in exchange for certain benefits. Sometimes, the benefits are as simple as military protection. In the United States, citizens are expected to obey the laws of the land, as expressed through the Constitution. This is in exchange for protection of their “life, liberty and pursuit of happiness.” Social contracts can be voluntary or involuntary, and can be observed in almost every type of political system, democratic or otherwise. Sometimes, a social contract involves those who are ruled to pledge fealty, as well as their livelihoods and productivity, to the ruling class. There are two types of social contracts. The first is a voluntary social contract. This is where the people agree to submit to the ruling class. Keep in mind that even though this agreement is voluntary, it does not always mean that those who are ruled are entitled to certain privileges, such as freedom of speech. In this situation, the people may simply need protection from outside threats. An involuntary social contract is when the ruling class dominates in a given territory and demands obedience from the people. In this case, those being ruled are simply pushed into a social contract. In some instances, disagreement has led to banishment or death.

There are also implicit social contracts as well. For example, most US citizens are born into their social contract. This is why some Americans often take their social contract for granted. By being born into citizenship, Americans may never need to actualize, or act upon, their citizenship. They benefit from a system that protects their rights and liberties, even when they choose not to obey the law. In contrast, there are other US citizens that are born into this social contract, and instead go through a formal process to become US citizens. This process is referred to as naturalization. Naturalization is the process by which noncitizens formally become citizens of the country they reside in. Naturalization is a long process that requires multiple steps, including but not limited to background checks, oral examinations, paperwork, and finally pledging allegiance to your host country in a formal ceremony. The process of naturalization is a good example of a voluntary and formal social contract where a citizen pledges obedience and allegiance in exchange for the benefits of being a citizen.

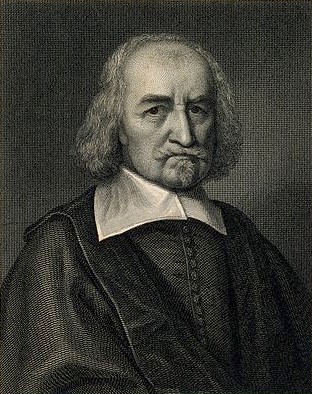

Social contract theory is often credited to certain philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Hobbes was the earliest of these thinkers, living between 1588 and 1679. While Hobbes was known for many scholastic contributions to history, politics, math and physics, he contributed greatly to political science, most notably the concept of a social contract. Hobbes acknowledged that all people act within their own self-interest, and in acting in their own self-interest, will make calculations to ensure their survival. Hobbes inherently saw human beings as selfish. For him, the state of nature was unstable and dangerous. Hobbes wrote that life was, “nasty, brutish and short”.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=312&height=394)

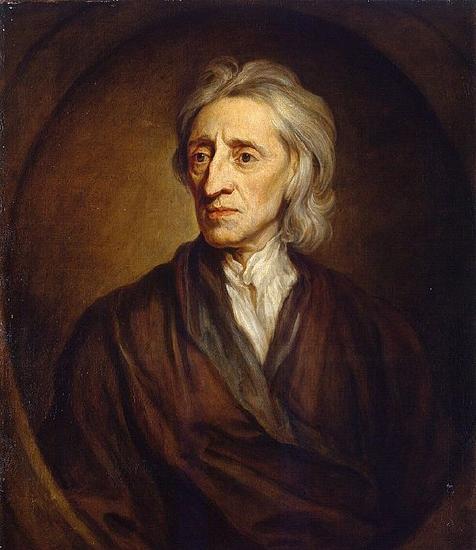

Locke lived between 1632 to 1704 in the UK and is considered one of the primary Enlightenment thinkers of his time. Locke contributed to social contract theory in his masterpiece, Two Treatises of Government. Locke set out the principles of natural rights, where he believed that all people were born with “certain, unalienable” rights. These rights should be recognized by states. Governments are expected to protect these natural rights through their political institutions and structures. In contrast to Hobbes, Locke thought positively about humankind. But like Hobbes, he believed in the power of the state, which did a better job of protecting its citizens. Again, Hobbes favored a more authoritarian government, believing that the state needed to control the masses, for their own good. Whereas, Locke believed humans were perfectly capable of living peacefully with each other, with no need for an authoritarian state. Even though Locke’s work did not gain widespread attention during his lifetime, it heavily influenced the US founding fathers. Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson borrowed heavily from Locke, with certain phrases in the US Constitution taken directly from Locke’s writings.

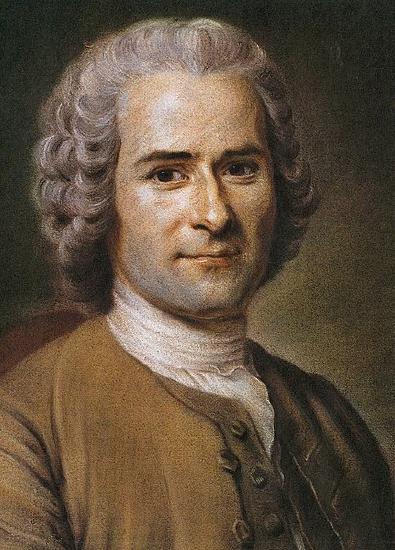

“Men are born free, yet everywhere are in chains,” remarked Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the opening lines of his 1762 work, Du Contrat social, or The Social Contract. In this publication, Rousseau continues the discourse on social contract theory and argues that society does not lend itself to equal and equitable treatment of those within society. Instead, society imprisons people with various “chains” and suppresses their natural born rights and liberties. To Rousseau, the only type of authority is only legitimate in society if it comes from the consent of all people. All people must agreed to a government in order to protect their interests, but in this contract, there must be a “unified will” which takes into consideration the interests of the people for the common good.

Taking this logic of the social contract back to the historical context, an early version of social contract can also be observed in ancient Greece, which is also credited with the first democratic state. In Ancient Greece, a system was established wherein elite men could participate in government and representatives could work on behalf of the people. Democracy comes from the Greek words, demo and kratos, meaning rule by the people. Broadly defined, democracy is a political system wherein government is dictated by the power of the people. A direct democracy is where every single citizen is able to be involved in the legal process and able to have some amount of power over the laws of society. A representative democracy is one where the people elect representatives to serve on their behalf to make the laws and rules of society. Ancient Greece did not have a perfect democracy as many members of the population were excluded from decision-making processes, like slaves (both male and female) and women were excluded from political processes. Nevertheless, the social contract here, in hindsight, was that the people of Ancient Greece submitted to the ruling class, through somewhat representative leadership, in order for protection from the political system.

Following the fall of the Roman Empire in 489 ACE, Western Europe fell into chaos. No longer were the citizens of these areas protected by the former social contract. Northern hordes came down and would attack territories, leaving most of the regions of the former Roman Empire in disarray. The circumstances were not ideal and most people during this time lived under constant duress with no protection of their person or property. Around 900 ACE, the system of feudalism arose. Feudalism was a system or social order that arose out of the middle ages, particularly in Europe, wherein peasants (sometimes called Serfs) were forced to provide members of the upper class with their crops, produce, goods as well as their services, fealty and loyalty. The upper class, usually Nobles, would provide some level of protection to the Serfs in exchange for their products and services. Consider feudalism in light of the social contract. Though not necessarily ideal, the Serfs were able to exchange their goods, services and fealty in exchange for some level of protection of their lives and property.

Overall, the story of government comes from this historical reckoning of the social contract and the drive for social order. From this, we can talk more directly about the formation of states, which is a common theme throughout political science and the comparative politics field.

Defining Terms

One of the most frequently used words in the study of comparative politics is the word state. At first glance, many students will see or hear the word state and think of, perhaps, subnational governments, like states in the United States like Montana, Wisconsin, New York, and so forth. This is not the way the word is interpreted within the field of comparative politics. Instead, a state is defined as a national-level group, organization or body which administers its own legal and governmental policies within a designated region or territory. Outside of the comparative discipline, many people tend to use the terms state, country, government, regime, and nation interchangeably. Within comparative politics, each of these terms is distinct, and have different implications when attempting to observe the political landscapes around the world. Since States tend to be the major political actors in the global arena, it is vital to have a firm grounding in understanding what states are, how the term state relates to other concepts and terms within comparative politics field, and how comparativists set out to study states and their actions. Using the correct terms in the right context will empower you to be able to interpret comparativist literature and research, and perhaps add your own contributions to the field someday.

If a state is a national-level organization which administers its own legal and governmental policies within a designated region or territory, what are nations and countries and how are they different or similar? State tends to have a narrower meaning than both a nation and a country, and relates more specifically to how a designated territory operates politically. A nation can be broadly defined as a population of people joined by common culture, history, language, ancestry within a designated region of territory. A country is similar, but tends to encompass aspects of both the nation and the state. A country is a nation, which may have one or more states within it, or may change state-type over time. For instance, consider the country, Russia. Russian history tends to be credited with its onset in the 9th century with the Rus’ people. The Rus’ state was established in 862 ACE, and encompassed much of modern day Russia as well as parts of Scandinavia. The Kievan Rus’ state followed the Rus’ state, but eventually fell apart during the Mongol invasions between 1237 and 1240. While Moscow grew to be a significant hub for business, politics, and society, the Russian region at this time was largely stateless and operated under the system of feudalism.

As mentioned above, feudalism was a system or social order that arose out of the middle ages, particularly in Europe, wherein peasants (sometimes called Serfs) were forced to provide members of the upper class with their crops, produce, goods as well as their services, fealty and loyalty. The upper class, usually Nobles, would provide some level of protection to the Serfs in exchange for their products and services. Eventually, Rus’ became a unified country Grand Duchy of Moscow, and became a major force within the region. (Briefly consider Tsardom, Imperial Russia…rise and fall of USSR…) Over time, the way Russia was ruled varied greatly, whether ruling came from a noble class, a royal bloodline, installment of a leader, or election of leadership. Let’s say a country, being a nation with shared values and heritage, is the hardware needed for a state within the world, then the regime is the software which tells the country or nation how to operate. The hardware, in this case, tends to last longer and be bound by similar history and values whereas a country or nation’s regime type can vary based on shifting values and challenges of the time period. Therefore, Russia has a common territory, history, language, ancestry, but has been led by different states over time.

One of the important characteristics of a state is its ability to independently organize its own policies and goals. As defined in Chapter One, sovereignty is fundamental governmental power, where the government has the power to coerce those to do things they may not want to do. Sovereignty also involves the ability to manage the country’s affairs independently from outside powers and internal resistance. If a state does not have the ability to manage its own affairs and issues, it will not be able to maintain its power over what happens. Power, broadly defined, is the ability to get others to do what you want them to do. Soft power means being able to get others to do what you want them to do using the methods of persuasion or manipulation. Hard power, in contrast, is the ability to get others to do what you want using physical and potentially aggressive measures, for instance, like fighting, attacking or through war. Both types of power hold critical places in the world of politics. It is critical to be able to convince others of a course of action from the perspective of a state, sometimes this ability to convince will come from simple persuasion or discussion of the merits of a certain course of action. Other times, there may be heavy resistance to an idea or plan, and some have chosen to use physical violence to get their policy goals achieved. Physical power is important in cases where a state must still defend itself from outside powers. If a state is unable to defend itself physically, even the most benevolent policy goals and objectives would be rendered meaningless because the state could cease to exist if attacked.

States must have both authority and legitimacy in order to operate effectively, or at the very least, to exist for some period of time. Legitimacy can be defined as the state’s ability to establish itself as a valid power over its citizens. Authority is another important piece of a state’s existence. Authority is defined as having the power to get things done. If we put these two terms together, a state is legitimate in its operations if it has the authority to make decisions and carry out its policy goals. Traditional legitimacy occurs when states have the authority to lead based on historical precedent. For instance, there are states in the political system where there is a legitimate authority to lead, but no defined or operationalized constitution, or set of rules and laws. A second type of legitimacy is called charismatic legitimacy, and it means that citizens follow the rules of a state based on the charisma and personality of the current leader. Legitimacy, in this scenario, also does not come from a written constitution accepted by the representatives or leaders of a country. This type of legitimacy can be flimsy as it is contingent on the charisma of a particular leader. When that leader dies or gets removed from office, will the state continue to stand, or will citizens no longer see legitimacy of authority from the government in the absence of that charismatic leader?

The last type of legitimacy is called rational-legal legitimacy, and it occurs when states derive their authority through firmly established, often written and adopted, laws, rules, regulations, procedures through a constitution. A constitution can be understood as a state’s described laws of the land. Authority and legitimacy can be consolidated and, if accepted by the people, it becomes the operating manual and handbook for how society should run. Each of these forms of legitimacy, especially when taken together, can enhance a state’s ability to function. If, for instance, there is a written and adopted constitution, and it has been transparently drafted and considered by representatives of a state, individuals will know what the rights and rules are of their given society. In time, as laws and norms are followed and accepted, there also becomes a historical precedent that individuals are more likely to accept (traditional legitimacy). Finally, if there does happen to be a charismatic leader, they may be able to garner further support from the people to deepen a state’s legitimacy and potentially grow the political agenda to meet further needs of society.

With these important terms considered, we can now more formally consider the many types of state and regimes that exist today, as well as the ways in which regimes may shift in form and function over time to either serve the needs or the people or the desires of the ruling classes.