6.5: Comparative Case Study - Gender Gaps in India and Japan

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 135854

- Dino Bozonelos, Julia Wendt, Charlotte Lee, Jessica Scarffe, Masahiro Omae, Josh Franco, Byran Martin, & Stefan Veldhuis

- Victor Valley College, Berkeley City College, Allan Hancock College, San Diego City College, Cuyamaca College, Houston Community College, and Long Beach City College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Compare aspects of two different societies which had caste system

Introduction

In the 21st century, conversations of political identity frequently center upon how individuals choose to identify themselves and categorize themselves into groups. The burden here tends to rest on individuals locating and assigning themselves an identity that matches their preferences and motivations. There are many examples of this from around the world, relating to racial, ethnic, cultural and gender preferences. Consider racial identity in Brazil: In Brazil in April 2021, over 40,000 political candidates were able to categorize their own racial identities differently than in previous elections. According to political scientist Andrew Janusz from the University of Florida, political candidates in Brazil "have some latitude to fluctuate on how they present themselves" in order to attract the voters they want to turn out at the polls.

Consider gender identity around the world. As of late 2021, there are sixteen countries which allow citizens to choose between male, female, non-binary or third genders on their passports. These countries include Argentina, Austria, Australia, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, India, Nepal and, most recently, the United States. In looking at democracies in Western Europe and the United States, the Pew Research Center has found that views on political and cultural identities have “become less restrictive and more inclusive in recent years.” Factors which have been historically important towards justifying one’s political identity, such as birthplace, religion, sharing a country’s customs and beliefs, and the ability to speak the dominant language in a country, have seen collectively decreased importance in terms of how political identity is interpreted today in Western Europe and the United States.

Considering these examples among many, some could argue the 21st century has brought more opportunities for societies to design and assign their own identities in alignment with their preferences and ambitions. Drawing this conclusion, however, downplays the reality that there are still many countries in the world where political identity, as well as other forms of identity, tend to be imposed, rather than chosen for oneself. Furthermore, debate over political identities is still heated around the world, even in places where it seems values of inclusion are being given greater weight.

Although Japan and India are both democracies, and both have constitutions which ensure equal treatment of citizens under the law as well as freedom from discrimination based on race, religion, gender and so forth, both countries have struggled greatly with improving gender equality in various segments of society. Generally, gender gaps are measured in regards to women in the economy (their participation and earning relative to men), women’s access to health, and women’s representation in politics. In all three areas, India and Japan have struggled and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have worsened already large gender gaps in both countries. Using the method of Most Similar Systems Design, this case study will compare two countries which, while both democracies of similar duration and emphasis on civil rights and liberties mentioned in their constitutions, have had difficulty with their policy approaches to decreasing gender gaps. Both countries struggle with historical and cultural remnants of gender roles which continue to pervade all aspects of women’s lives today. Although both countries are now democracies, with legal protections in place to ensure equal rights and prevent discrimination based on gender, these two countries have taken different action to treat current gender gaps.

Japan’s Gender Gaps

Full Country Name: Japan

Head(s) of State: Emperor and Prime Minister

Government: Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy

Official Languages: Japanese

Economic System: Mixed Economy

Location: Island in East Asia

Capital: Tokyo

Total land size: 145,937 sq mi

Population: 125 million

GDP: $5.378 trillion

GDP per capita: $42,928

Currency: Japanese Yen

Japan is an island in East Asia off the coast of China and Taiwan. Today, Japan has one of the oldest democracies in East Asia, and is the 11th most populous country in the world. Japan’s government system is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy where the Emperor is the Head of State, the Prime Minister is the Head of Government, and the Cabinet directs the executive branch. Legislative power is vested with the National Diet, which is a Congress that includes both a House of Representatives and a House of Councillors. Judicial power is vested in the country’s Supreme Court and some lower courts. The supreme law of the land is derived by the 1947 Constitution, which was created under the American occupation of Japan following World War II. Overall, Japan’s democracy is considered consolidated and stable, as the country has upheld free and fair elections, the rule of law, and freedom of the press. Nevertheless, an area of continuing concern in Japanese society is gender equality. Japan ranks 110 out of 149 countries worldwide according to the World Economic Forums’ 2018 Gender Gap Index.

Following the creation of the 1947 Constitution in Japan, which ended the reign of Emperor Meiji and the Meiji Period, Japanese powers were encouraged to initiate their own democracy and enforce democratic reforms. Nevertheless, the 1947 Constitution was mostly drafted by Americans, and reviewed and modified by Japanese scholars. Interestingly, the 1947 Constitution was written to institute democracy, but also written to not contradict the previous Meiji Constitution. In doing so, it was hoped that the people of Japan would more readily accept the new constitution.

Some of the main additions within this Constitution were those given to individual rights, including but not limited to: Equality before the law (freedom from discrimination), democratic elections, the prohibition of slavery, separation of church and state, freedom of assembly, speech association, press, right to property and right to due process. Women were granted the right to vote prior to the Constitution being formally adopted (women’s suffrage granted in 1945), and combined with the individual rights emphasized in the Constitution, it was hoped that women would enjoy equal rights and treatment as men. For a variety of factors, women in Japan have faced great challenges over the decades since World War II in terms of being treated equally under the law and within society. The delay and slow progress in women achieving equal outcomes may be due, in part, to historical context and culture.

Within the Meiji Era, women did not have legal rights of any kind, and they were expected to perform only household duties as directed by the male head of the household. From a historical and cultural standpoint, expectations of women have been strict. Women are expected to be modest, tidy, courteous, obedient and self-reliant. Women were to look well-kept and to be silent and compliant with male expectations and needs. In this vein, both male and female children were to be completely obedient to their parents. Women who expressed themselves or communicated their needs were considered troublesome or overly needy, which were not desirable characteristics. Female children were directed to perform duties to help around the house, while male children were given opportunities for schooling and eventual employment in various vocations. Although the 1947 Constitution did introduce sweeping changes that should have affected the status of women, many of the cultural norms from the Meiji period still stand today, with women being socially expected to be submissive and modest.

The treatment of gender roles does not seem to match the reality of life in Japan. Although there is a preference for women to maintain the Meiji existence, the vast majority of adult Japanese women work (almost 70% of all adult Japanese women are employed). At the same time, Japan has one of the worst documented gender gaps in terms of equal pay for women based on similar credentials and occupational levels as men. Indeed, the OECD noted that Japan has the second worst gender wage gap in the world.

Following other trends around the world with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, employment prospects and data worsened for Japanese women. Indeed, Japan’s women experienced larger reductions in their work hours, had a higher tendency to be furloughed, and were generally pushed from the workforce at a far greater rate than men were in the midst of the pandemic; so much so, the exodus of women in the workplace in Japan has been called the 'she-cession'. Although some recent gains in employment for women have occurred, economic recovery in regards to women in the world place has been slow, and raises questions about the overall ability for women to re-enter the workforce again over the coming years. The effect of the pandemic was particularly difficult for Japan’s women because of their traditional values on gender roles. In this vein, many believed, in the face of the lockdown and quarantines, women should be at home helping their children and tending to household responsibilities. Many women bore the brunt of all family-related obligations during the pandemic, and sluggish economic growth does not improve opportunities for women to return to work.

Inequality in the workplace is not the only area of concern for women in Japan today. Two other areas of concern is the lack of female representation within the political structures and the prevalence of sexism and gender discrimination overall. On the first point, although political parties in Japan have prioritized increasing the representation of women in their organizations, growth has been slow. Interestingly, survey results within Japan indicate that voters are not necessarily biased against candidates for their gender, but rather not many Japanese women run for political office. In line with the belief that women need to be submissive, modest and unambitious, running for office creates problems for each of these characteristics. Although 70% of adult Japanese women are in the workforce, the perception that women should be home with their children and handling household tasks is still firmly embedded in society.

Some research has indicated that Japanese women would be more likely to run for office if political parties made efforts to lend greater support and funding to support their candidacies. Some scholars have also argued that the current structure of Japan’s welfare system is not conducive for women running for office or holding high-level jobs in the workplace. This is because there is a perception that men need to be the main “breadwinners” of the household, and if a woman is not employed, the family is eligible for more government support for women to handle the raising of the children. If women are working in tandem with their husbands working, they will not be eligible for this extra government assistance, which could hurt their families. Data also indicates that women face stark gender-based discrimination and harassment in Japan, whether in the workplace, in schooling, or in society in general. According to a 2021 survey, almost 60% of Japanese women working in government experienced sexual harassment on the job, by both voters and other politicians.

India’s Gender Gaps

Full Country Name: Republic of India

Head(s) of State: President

Government: Federal parliamentary constitutional republic

Official Languages: Hindi, English (Plus over 430 native languages)

Economic System: Middle Income Developing Market Economy

Location: South Asia

Capital: New Delhi

Total land size: 1,269,219 sq mi

Population: 1.3 trillion people

GDP: $3.050 trillion

GDP per capita: $2,191

Currency: Indian Rupee

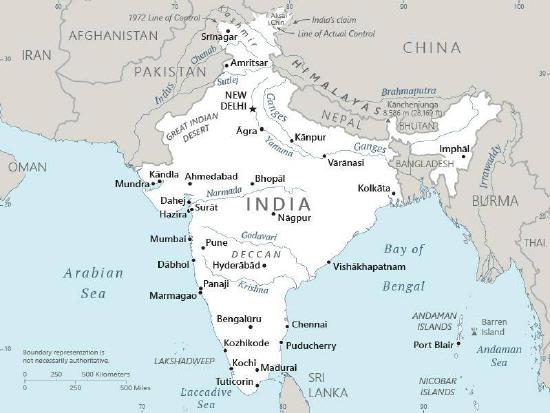

India is a country in South Asia, bordered by Pakistan, China, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Myanmar. India gained its independence from Britain in 1947, and redrafted its Constitution to install a democracy as a federal parliamentary republic. Under its new Constitution, India’s government has all three components of the executive, legislative and judicial branches. The executive branch contains a president with largely ceremonial duties, and a prime minister, whose role is the head of government and is tasked with wielding the executive powers. The prime minister role is appointed by the president with the support of the majority party in parliament at the time. As in the U.S. democracy, the executive branch’s powers are secondary to legislative powers. The legislative branch, which contains parliament, is tasked with making laws and performing all legislative functions. Finally, India’s judiciary is a three-tiered system which includes a supreme court and a number of high and lower courts.

India’s constitution is substantially longer than Japan’s, though similar to Japan’s, fundamental rights are within the first few sections of the entire document. Articles 14 and 15 of the Constitution ensure equality before the law as well as the prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth. All this being acknowledged, India is a democracy which also is labeled as having severe problems with gender equality and treatment. While Japan ranks 110 for gender gaps, India ranks 140 (slipping 28 spaces in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic). Like Japan, India has had a long history of abiding by strict gender roles. In Indian society, men are the “breadwinners” and the ones tasked with earning for their families, where women are responsible for reproduction of heirs and handling home duties (submissive to the head of the household).

Historically, women in India never held roles equal to men. Women were seen only as wives and mothers, and their positions were always subordinate to men. In this society, men drive all social, political and economic choices. Beyond this, the role of the women was to ensure, oftentimes, a male child. Male children hold significant roles in the family and, eventually, are tasked with performing last rites for the elders in the family, as well as ensuring the continuation of the family line. Under this system, women were expected to be highly moral and faithful, while men were encouraged to ensure male progeny, even if it meant being unfaithful. Over time, women’s rights in India did not improve, but steadily declined. The birth of daughters was not welcome news. Often, it may be more profitable to sell a daughter or woman as a commodity, rather than keep one in the family.

Although India’s constitution does recognize equal rights for men and women, and that individuals in India would be free from discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth, many conceptions of the role of women in society seem to persist today. The historical and cultural foundations of women in society are difficult to overcome. One of the reasons for India’s gender gap ranking is starkly different than Japan’s, which appears to be most manifest in gender wage gaps and treatment of women in the workplace, is because of India’s practice of sex selective abortion. Sex-selective abortion is a practice of terminating a pregnancy once the sex of the infant is known. In most cases, this means that if a child is known to be female, there may be motivation to end the pregnancy.

While abortion is legal with certain restrictions in India, the practice of sex selective abortion is not. Nevertheless, it is believed that sex selective abortions do take place at a high rate given the grossly uneven ratio of males to females in Indian society. According to the United Nations, both India and China account for more than 90% of all sex selective abortions worldwide, with an estimated 1.5 million missing female births recorded each year globally. Various non-profits and human rights organizations have been working in India to decrease the practice of sex selective abortions, though it can be difficult to monitor these practices since they are not legal and these abortions may be practiced under unsafe or non-ideal circumstances.

Other reasons for India’s low ranking in terms of gender equality include the lack of women’s representation in politics, the lack of women in technical and leadership roles, unequal access to health care, major gaps between male to female literacy levels, expanding gender wage gaps, and an overall decrease of women in the workplace. Generally, the role of women in society is ranked according to women’s economic participation, opportunity and access to education and health care, and their representation in politics.

Case Analysis

Following the end of World War II, Japan’s 1947 Constitution was well-received by the public, and enabled Japan to maintain its historical and cultural origins while adopting democratic values. Their constitution had all the basic ingredients for building a liberal democracy where civil liberties and civil rights were respected. India’s situation was, in some ways, very similar to Japan’s, for instance, there was a priority from the beginning with the new Constitution to ensure equal protection under the law as well as ensuring individuals would not be discriminated on based on characteristics of note like religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth. Both India and Japan are democracies that continue to struggle with gender gaps, and yet, they do differ in their overall trajectory of progress on these issues. Although prior to the pandemic, India had made major leaps in terms of narrowing gender gaps, the COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked terrible outcomes for the treatment of women in India. One of the main areas India will need to focus on is the health of women in society, ensuring women have access to affordable and quality healthcare to protect their interests and prospects at survival. Although Japan’s women also bore difficult outcomes from the COVID pandemic, the Japanese government has established a new direction for many of its policies and initiatives relating to decreasing the gender gaps. One of its plans, the Fifth Basic Plan for Gender Equity, calls for major changes to support women in the workplace and to increase their representation in political parties and politics in general.