8.3: Comparative Case Study - Germany and China

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 135867

- Dino Bozonelos, Julia Wendt, Charlotte Lee, Jessica Scarffe, Masahiro Omae, Josh Franco, Byran Martin, & Stefan Veldhuis

- Victor Valley College, Berkeley City College, Allan Hancock College, San Diego City College, Cuyamaca College, Houston Community College, and Long Beach City College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify and categorize the different economic systems in Germany and China.

- Compare and contrast the various economic outcomes in relation to the political regimes in Germany and China.

- Analyze the implications for public policy in each of these countries in relation to their economic systems.

Introduction

From a political perspective, China and Germany have little in common. China is a socialist republic led by a single, communist political party and communist elites, while Germany is democratic, federal parliamentary republic where two main political parties vie for dominance. China’s political system is authoritarian where national political leaders are selected without nomination or election by the people, most political opposition is suppressed, and media, news and information for the public is mostly controlled by the state. Germany’s political system enables participation of its citizens in politics, representation of opposing views, a free media, and the protection of civil liberties. China and Germany also operate under very different economic models. China’s economy is a market-oriented, mixed economy where the majority of economic ventures are state-owned and dominated by the political interests of the single communist political party. Although not the direct opposite or anthesis of China’s controlled market economy, Germany’s economy is different from China’s in a number of respects. It has a social market economy that brings in aspects of capitalism, particularly the prospect of free market competition, but also protects its economy from unbridled competition at the expense of its citizens. The main difference between China and Germany’s economic system is the extent to which the government validates its role in the control and/or management of the global market system. In short, the Chinese government dominates the market, mostly through state-owned enterprises, whereas the German government prefers to influence the market, mostly through regulation.

Although China and Germany are different in terms of their political and economic systems, they do share some fascinating similarities in terms of their global trading approaches. Both China and Germany are political centers for regional trading blocs, and both maintain mutual dependency on their regional partnerships. Further, both China and Germany depend heavily on their exports, with Germany’s exports accounting for over 50% of their total GDP and China’s exports accounting for almost 25% of its total GDP. (For reference purposes, the US only exports what amounts to less than 15% of its GDP). Although their economic systems differ, it is interesting to point out that both China and Germany face similar economic challenges and vulnerabilities based on their over reliance on upholding export economies. Both systems, relying on their export economies, have created circumstances where their domestic production surpasses their own domestic capacity to use/consume/acquire goods. If German exports were to unexpectedly decrease or decline, domestic consumption would need to increase to levels not feasible with Germany’s current population. China would also face severe economic outcomes should exports decline, but the domestic challenges would be different for China. China has a large population which lacks the purchasing power to buy the goods produced by China, so sharp declines in exports would also be detrimental to China. Therefore, two very different market systems find themselves with a similar problem of managing their export economies carefully in order to ensure domestic economic and political stability.

Using the method of Most Different Systems Design, this case study will compare two countries, China and Germany, considering their different economic structures but similar economic challenges in the coming decades.

Germany’s Social Market Economy

- Full Country Name: Federal Republic of Germany

- Head(s) of State: President & Chancellor

- Government: Federal Parliamentary Republic

- Official Languages: German

- Economic System: Social Market Economy

- Location: Central Europe

- Capital: Berlin

- Total land size: 137,847 sq. miles

- Population: 80 million (July 2021 est.)

- GDP: $4,743 trillion

- GDP per capita: $53,919

- Currency: Euro

Germany currently has the 5th largest economy in the world according to its GDP and is one of the largest global exporters in the world. Germany is considered to have a highly developed economic system utilizing a social market economy. The concept of a social market economy originated in 1949 under the leadership of Chancellor Konrad Adnauer. As discussed above a social market economy is a socioeconomic system that combines principles of capitalism with domestic social welfare considerations. It borrows the capitalist principles of fair competition and competitive advantage. Fair competition in capitalism affirms that industries will work to maximize their output and minimize costs to compete with similar industries, forcing the market to provide competitive options to consumers. Fair competition lends to the economic concept of comparative advantage, which again refers to the goods, services or activities that one state can produce or provide more cheaply or easily than other states. While Germany’s economy hinges on fair competition and competitive advantage, it does so with an eye towards the effects and potential hazards of enforcing pure capitalism on social welfare. A social market economy will try not to force competition at the cost of its country’s social welfare. It is useful to look at the Roots of Germany’s social market economy to understand the current status of Germany’s economy today.

Germany’s Economic History

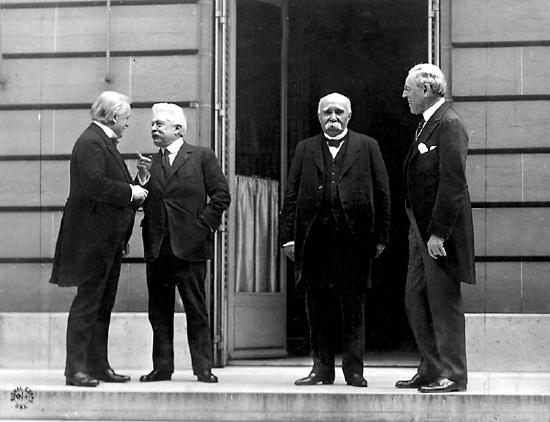

Germany’s social market economy was the product of dire economic conditions coming out of World War II. Coming out of World War II, the lessons of the prior 45 years weighed heavy on the minds of German politicians and economists. Following World War I, Germany was thrown into a weak democracy under the Weimar Republic. Germany suffered greatly under the terms of the Versailles Treaty, which ended the first World War. In addition to the social and economic turbulence caused by the end of the war, Germany was forced to drastically reduce its military. Under the Treaty of Versailles, it was also to take full responsibility for World War I and pay exorbitant reparations to the Allies, and ultimately relinquish some of its territory. Germany signed the Weimar Constitution on August 11st, 1919, and weak political parties attempted to shift power away from the German military. Two of the main political parties at that time included the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USDP). German’s leadership faced dire economic challenges in the years following World War I.

The main challenge facing the Weimar Republic was hyperinflation. Hyperinflation is defined as a much more severe form of inflation that can have deleterious effects on all aspects of a country’s social, political and economic situation. Hyperinflation occurs when inflation exceeds 50%. When the Weimar Republic was forced to pay high reparations and war debts to the Allies following World War I, the German government tried to print more money. At the end of the war, German debt to the Allies totaled 132 billion gold papiermarks, the equivalent of $33 billion U.S. dollars at that time. (The German currency at this time was called the papiermark.) Germany abolished its use of the gold standard to produce more printed money, and in doing so, it induced a state of hyperinflation where inflation rates soared beyond 20,000%, with prices doubling every 3.7 days. For reference, at the end of World War I, the exchange rate of papiermarks to the U.S. dollar was 4.2 papiermarks to the U.S. dollar; by the end of 1923, the rate was 1 million papiermarks to the U.S. dollar. Hyperinflation meant citizens could not buy basic goods, and many Germans went hungry. It also led to Germany to become delinquent on their reparation payments, leading French and Belgium to justify occupying the Ruhr Valley in Germany as payment. The German economy folded, and the Weimar Republic was forced to adopt a new currency, called the Reichsmark in 1924. The new currency stabilized the economy but did not take away all of Germany’s economic woes. Instead, economic troubles continued and planted the seeds for further societal distress.

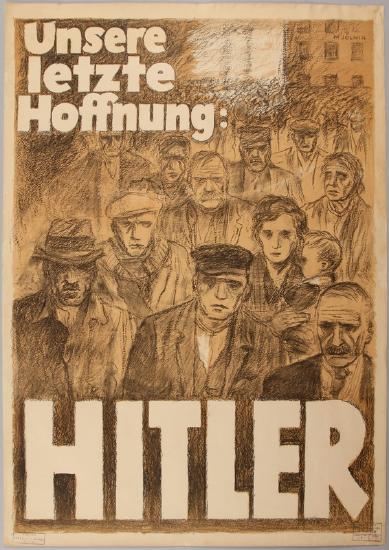

At the height of the economic woes of 1923, Adolf Hilter gained notoriety as he advocated for the politically right-wing party, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDP), also known as the Nazi party. In November 1924, Adolf Hitler led an attempt to overthrow the Weimar Republic in what later became called the Beer Hall Putsch in Munich. Over two thousand Nazi party members worked to aid Hitler in overthrowing the government, but the coup d’etat was squashed by the local police. Sixteen Nazi party members were killed in the attempt, and their deaths were used as further motivation to attempt to overthrow the democratic government in Germany. Much of what drew members to the Nazi party at that time was the devastating economic conditions of hyperinflation, unemployment and poor working conditions. The economic troubles, combined with the weight of defeat for World War I, helped raise the ire and unrest of the German people. Although Hitler was sent to prison following the Beer Hall Putsch, he used that time to draft his autobiography, Mein Kampf (meaning, My Struggle).

Over the coming decade, Hitler was able to rally the German people by lambasting the Treaty of Versailles, calling it a disgrace to the German nation. He promoted German pride and ultranationalism, promising to unite all the German people in and outside of Germany. He scapegoated many of Germany’s problems on minority groups, particularly Germany’s Jewish population, and on the communists, denouncing their beliefs. In 1933, the Nazis emerged as the larget party in the Reichstage or German parliament. The President of Germany at that time, Paul von Hindenburg, was compelled to appoint Hitler as Chancellor of Germany. Hitler leveraged a manufactured hatred for the Jewish population, communism, and the architects of the Versailles Treaty, to transform Germany into a one-party dictatorship with a state-controlled economy.

Life under Nazi rule initially yielded strong economic outcomes. Hitler’s leadership and command of a state-controlled economy enabled Germany to experience six years of rapid economic growth. This mercantilist approach allowed Germany to pursue its military objectives. After World War II, Germany was in ruins and most of the most physical capital that had been accumulated had been destroyed in the war. This led German leaders to declare Stunde Null, or zero hour, where the country was going to need to rebuild itself in order to survive. Post-war German economists advocated for radical change. The Nazi regime had overseen a state controlled economy with emphasis on corporate control. Going away from a completely statist approach, German economists advocated greater free-market capitalist principles. At the same time, The German government also wanted to ensure that the people’s welfare, particularly those of the workers, were protected. Transitioning to a fully capitalist model was too risky, and it was believed that not all workers or citizens in general would be able to compete effectively. This led to the adoption of a social democratic political economy.

Germany’s Economy, Present Day Circumstances and Challenges

Germany is Europe’s largest economy, the fifth largest economy in the world according to GDP, and the largest exporter of goods in Europe. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns which began in March 2020, Germany had experienced consistent growth for the past 10 years. When the pandemic struck, Germany’s economy contracted by 5% led by a decline in exports. Still, relative to how other European economies performed, Germany fared better than many of its EU partners. For reference purposes, the Chinese economy contracted by almost 7%, and the U.S. economy contracted by over 19% in the first three months of the pandemic. The economic challenges of the pandemic facing Germany are not unique, as the country grapples with intermittent shutdowns to curb the spread of COVID-19, unemployment, initial disruption of imports and exports, and the social fallout experienced by frequent shutdowns and isolations.

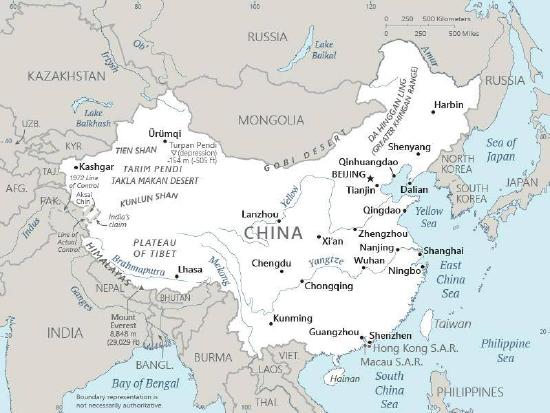

China’s Market-Oriented, Mixed Economy

Full Country Name: People’s Republic of China

Head(s) of State: President

Government: Communist party-led state

Official Languages: Standard Chinese

Economic System: Market-oriented, mixed economy

Location: Asia

Capital: Beijing

Total land size: 5,963,274.47 sq. miles

Population: 1.3 billion (July 2021 est.)

GDP: 19.91 trillion

GDP per capita: $14,096

Currency: Renminbi

China has the second largest economy in the world according to GDP, and is the world’s largest exporter and trading nation. However, if measuring economies based on Purchasing Parity Power, then China has the world’s largest economy. Purchasing Parity Power (PPP) is a metric used to compare the prices of goods and services to gauge the absolute purchasing power of a currency. China pursues state capitalism, where a high level of state intervention exists in a market economy, usually through state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Part of the reason for the high state intervention stems from China’s political system, which is authoritarian under the sole leadership of a single political party, the Chinese Communist Party. As one may suspect, over 60% of China’s industries and enterprises are state-owned. It is useful to look at the roots of China’s market-oriented, mixed economy to understand the current status of China’s economy today.

China’s Economic History

China’s Communist Party came to power in 1949 after they defeated the nationalists in a brutal civil war. The leadership intended to modernize China as fast as possible, with a desire to become more powerful. From 1949-1952, the Chinese government prioritized projects to repair transportation, communications, and power grids. Military installations and equipment, as well as basic transportation, communications and power systems had been destroyed during the war and were badly in need of repair or rebuilding. Under government direction, the banking system was centralized under the People’s Bank of China. Moving towards a state-controlled economy, the state began to acquire more and more control over various industries. By the end of 1952, only 17% of industries were not state-owned.

After having stabilized the economy, China prioritized industrialization. Chinese government officials looked to the Soviet model to attempt to industrialize in a logical and linear way. Soviet officials were even welcomed in the country to help devise the best way to industrialize. By the end of 1956, all firms were state-owned. During this time, the agricultural industry was largely revamped and, to some extent, considered to be secondary. Agriculture was not invested in, though agricultural output increased during this time period due to more organization and cooperation of those working in the industry.

In 1958, Mao Zedong determined that the Soviet model was not working for China. Instead, Zedong introduced what was called the Great Leap Forward, which was a plan which asked the Chinese people to spontaneously increase production in all sectors of the economy at the same time. For this initiative, communes were created to make Chinese farmers and workers work together cooperatively to increase output. These communes often had 20 to 40,000 members at a time, all tasked with combining their resources to produce more agricultural output. While the agricultural sector was working to increase output, the same expectations were also put on the industrial sector. The economic results of the Great Leap Forward were disastrous for China. The first year yielded strong outcomes for both the agricultural and industrial sectors, but the subsequent years were poor. Due to bad weather conditions, poor allocation of resources, and poorly constructed equipment, agricultural output plummeted from 1959 to 1961. Poor water management helped contribute to widespread famine, which resulted in approximately 15 million people dying of starvation and a significant drop in birth rates.In the meantime, industries were expected to keep increasing output, but the strain on the workers was too great, and industrial output also declined.

Between 1961 and 1965, China again tried to reconstruct its economy, working to entirely replace the concept of the Great Leap Forward. China reformed all of its agricultural practices, including lowering taxes and providing more equipment. The government attempted to decentralize control of various industries to local governments for them to manage resources based on their unique needs. By 1965, economic conditions were again stable, and the focus from the Chinese government was to seek balanced growth across both agricultural and industrial sectors.

In 1966, Mao announced the Cultural Revolution, which was a socio-political and economic movement that sought to expel capitalists and promote the Communist ideology. Attacking capitalism, Mao alleged that the bourgeoisie attempted to infiltrate China with the goal to overthrow the communist government. Bourgeoisie is a term that refers to the upper middle classes, who often own most of a society’s wealth and means of production. Mao attempted to incite young people to violence against those who he accused of perpetuating capitalist practices. Mao’s sayings and wisdom were compiled into the Little Red Book, which became both a required reading of China’s militant communist youth movements, named the Red Guards. In general, the Cultural Revolution had devastating effects on China’s economy. The distraction and disruption of political fighting did not improve agricultural or industrial output. Instead, the disruptions to economic output put a strain on resources, labor and equipment, which many researchers said led to the death of millions.

Between 1961 and 1965, China again tried to reconstruct its economy, working to entirely replace the concept of the Great Leap Forward. China reformed all of its agricultural practices, including lowering taxes and providing more equipment. The government attempted to decentralize control of various industries to local governments for them to manage resources based on their unique needs. By 1965, economic conditions were again stable, and the focus from the Chinese government was to seek balanced growth across both agricultural and industrial sectors.

In 1966, Mao announced the Cultural Revolution, which was a socio-political and economic movement that sought to expel capitalists and promote the Communist ideology. Attacking capitalism, Mao alleged that the bourgeois (a term which means social class, and refers to the upper middle class.) had infiltrated China, and were seeking to own all means of production to perpetuate their own economic superiority. Mao attempted to incite young people to violence against those who perpetuated capitalist ideology. A book of Mao’s sayings and wisdom was compiled into the Little Red Book, which became both a required book of all Red Guards (rebels groups) within the country. In general, the Cultural Revolution had ill effects on China’s economy. The distraction and disruption of political fighting did not improve agricultural or industrial output. Instead, the disruptions to economic output put a strain on resources, labor and equipment.

Mao died in 1976, and in 1978, the Communist Party under Deng Xiaopeng moved the country in a new direction. China reduced government controls, enabled market mechanisms, and generally attempted to reform the economy. This was not a sudden move away from communism, but a gradual move towards a mixed economy, designed to stimulate growth. These reforms slowly opened China to global trade, which improved economic outcomes. The success of these incentivized China to keep pursuing this strategy, and to also invest heavily in the education and training of government officials and future business leaders. China became a member of the World Trade Organization in 2001, cementing its transition from a command and control economy, to a largely state capitalist society. China was able to survive the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, referred to as the Great Recession in the US. China has consistently been the fastest growing economy over the past forty years.

China’s Economy, Present Day Circumstances and Challenges

The COVID-19 pandemic was the first time China’s economy contracted since adopting capitalist reforms, shrinking 6% in 2020. Even though China was the first country affected by the pandemic, it has also been the first to bounce back from its economic effects. The economy recovered with a growth rate of 8.5% in 2021. Nevertheless, the pandemic has impacted the Chinese economy, possibly for the long-term. China is still export-heavy, but some industries are experiencing a decline. Industries in decline in China include telecommunications, fabric/clothing, coal, and logging. These declines are a symptom of changing supply and demand following the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to trends in other countries, the pandemic hit women in the workforce disproportionately hard, with many women being made to decide whether to continue working or to support their families during the crisis. Also, employment opportunities for almost all sectors decreased, which put a strain on new graduates.

Importantly, China’s continued growth and low inflation rates has raised questions in the international community. Under a largely authoritarian regime, there have been questions over how accurate China’s reporting on economic growth and output is. Some have contended that the level and extent of continued economic growth is not feasible, and sometimes the data reported does not appear legitimate. In tandem with this, the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) has repeatedly ranked China as having problems with corruption on every level. For instance, the reality that China reported little to no economic contraction during the 2008 recession, and its ability to bounce back so quickly from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, raises concern over how transparent China is about their economic performance.

Export-Based Economic Problems

In reviewing the cases of China and Germany, it becomes apparent they share a similar problem: how to handle economies which are largely export-based. Both China and Germany’s political leaders need to constantly and carefully balance the domestic concerns of their economies alongside their global ‘customers’ who depend on their exports. If the global customer base fails, or switches trade partnerships, China and Germany’s economies may be unable to thrive. Beyond this, relying on exports leaves states vulnerable to the economic conditions of those they trade with - if a state is no longer able to afford the product or buy the goods, the exporter will struggle. This can cause dangerous political conditions in China and Germany. Increasing unemployment due to economic slowdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent global recession, may lead its citizens to question their government’s legitimacy. We see this with the rise of the far right in Germany and with the increase of public discontent in China. Will the fallout from the pandemic lead to political changes as well? Only time will tell.