Learning Goals

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Remember the process of writing a research paper plan

- Create a research paper plan

A goal of an Introduction to Political Science Research Methods course is to prepare you to write a well-developed research paper that you could reasonably consider submitting to a journal for peer review. This may sound ambitious, since writing a publication-quality research paper is typically reserved for faculty who already hold a doctoral degree or advanced graduate students. However, the idea that a first or second-year student is not capable is a tradition in need of change. Students, especially those enrolled at community colleges, have a wealth of lived experiences and unique perspectives that, in many ways, are not permeating throughout the current ranks of graduate students and faculty.

Writing a research paper should be viewed like managing a project that consists of workflows. Workflows serve as a template for how you can take a large project (such as writing a Research Paper) and disaggregate it into specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and timely tasks. This is called “project management” because you are taking a “big” project, organizing it into “smaller” projects, sequencing the smaller projects, completing the smaller projects, and then bringing all the smaller projects together to demonstrate completion of the “big” project. In the real-world, this is a valuable ability and skill to have.

We have all project managed; we just never call it that. For example, have you had a plan a birthday party? Or maybe organize a family dinner? Or maybe write a research paper in high school? The party, dinner, and researcher paper are all examples of projects. And you managed these projects from beginning to end. The result of your efforts was a “great time” or “delicious dinner” or “excellent work”. In other words, don’t underestimate your ability to successfully manage a complex project.

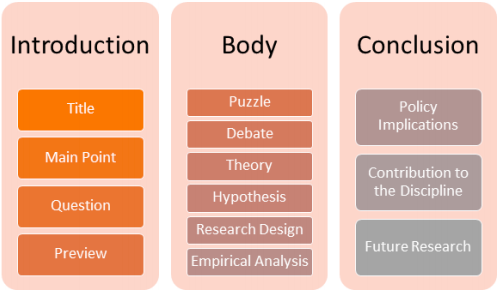

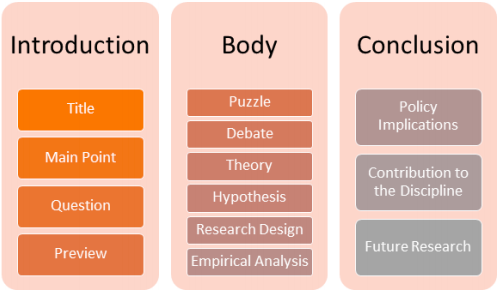

The process of writing a political science research paper closely follows the process of analyzing a journal article. A research paper consists of an introduction, body, and conclusion. The introduction contains the title, the main point, question, and preview of the body. The body includes the puzzle, debate, theory, hypothesis, research design, and empirical analysis. Finally, the conclusion contains policy implications, contribution to the discipline, and future research.

\(\PageIndex{1}\): Visualization of research paper parts

A crucial difference between analyzing a journal article and writing a research paper is a literature review. When analyzing a journal article, you don’t search for a literature review. Rather, you look for the outputs of a literature review process: puzzle, debate, and theory. A literature review is your reading and analysis of anywhere from 10 to 100 journal articles and books related to your research paper topic. This sounds like a lot, and it is. But don’t be exasperated by the number of articles or books you must read, simply recognize that you need to absorb existing knowledge to contribute new knowledge.

A literature review can serve as an obstacle for the first-time writer of a political science research paper. The reason that such an obstacle is just the sheer amount of reading that one needs to engage in in order to understand a topic. Now, we may have difficulty in reading because we have a learning disability or deficit disorder. Or, reading can be challenging because we don’t have access to the articles and books that help make up our understanding of a topic. The key is not to get caught up in what we cannot do what we have trouble doing, but rather to focus on what we can accomplish.

How can we conduct a literature review? First, we want to select a topic that we are interested in. Now there’s a range of things in the world that we can explore. And because the world is complicated, there is a lot that we can explore. But some straightforward advice is to research something you care about. What is something from your personal experiences, or what you observed in your family and community, or what you think society is grappling with, that you care about? The answer to this question is what you should research.

After we selected a topic, we should search for more information by visiting our library, talking with a librarian, meeting with our professor, and visiting reputable information sources online.

The campus library serves as a repository of information and knowledge. Librarians are trained professionals who understand the science of information: what it is, how it’s organized, and how we give it meaning. So, you can meet with the librarian and ask for their help to navigate in person and online resources related to your topic. What a librarian may ask you, in addition to your topic, is what your research question?

You may be asking what’s the difference between a question and a research question? Frankly, one question has the adjective “research” in front of it. A question generally with the word: who, what, when, where, why, and how. On the other hand, a research question typically starts with why. A why question suggest that there are two things, also known as variables, that interact in a way that is perplexing and intriguing to you. For example, why do some politicians tweet profusely, and other politicians don’t even have a Twitter account? A secondary question is: what causes a politician to utilize social media? Now the answers to these questions require some research that something that you can do.

With your topic and research question in hand, you will be directed to books, journal articles, and current event publications to learn more about your topic. Sifting through the mountains of information that exist today is a skill. Honing this skill is a lifelong process because the information environment is constantly changing. For your purposes in writing a research paper, you should consult with your professor about what are reputable books, journals, and new sources. In political science, university presses, the journals of national and regional associations, and major news outlets all serve as reputable sources.

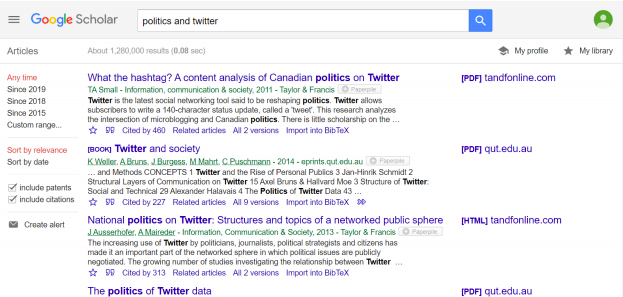

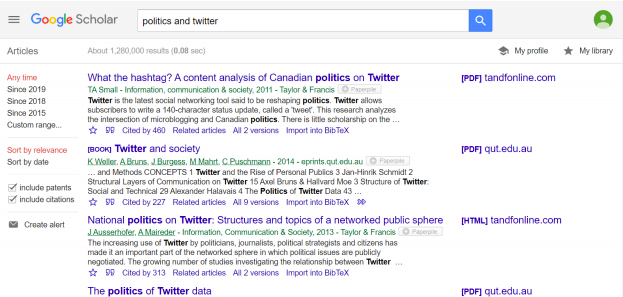

A go-to source for finding academic articles and books on a topic is Google Scholar. Unlike Google search engine, which provides results from all over the World Wide Web, Google Scholar is a search engine that limits results to academic articles and books. By narrowing the results that are provided, Google scholar helps you cut through the noise that exist on the Internet. For example, in my web browser I type in https://scholar.google.com/. In the search box, I type “politics and twitter” and below the following results appear:

\(\PageIndex{2}\): Output of Google Scholar search of “politics and twitter”

In this example, we see that there are over 1.2 million results. How do you decide on the 10, 20, or 100 articles and books to read? One way to shorten your reading list is to see how many times something has been cited. In the example above, we see that the article titled “What the hashtag?” has been cited 460 times. If an article or book is cited in the hundreds, or thousands, of times, then you should at its your reading list because it means that a lot of people are focused on the topic, or the findings, or the argument that that object represents.

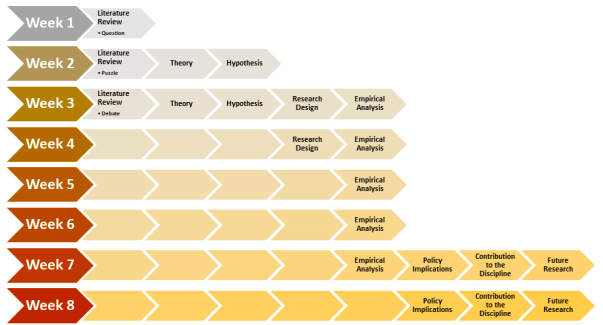

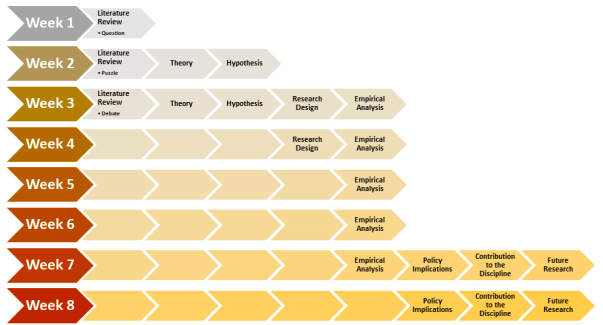

Writing a political science research paper is a generally nonlinear process. This means that you can go from conducting a Literature Review, and jump to Policy Implications, and then update your Empirical Analysis to account for some new information you read. Thus, the suggestion below is not meant to be “the” process, but rather one of many creative processes that adapt to your way of thinking, working, and being successful. However, while recognizing your creativity, it is important to give order to the process. When you are taking a 10-week or 16- week long course, you need to take a big project and break it up into smaller projects. Below is an example of how you segment a research paper into its constituent parts over an 8-week period.

\(\PageIndex{3}\): Proposed 8-week timeline for preparing your research paper