Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the process by which ideas and observations are turned into concepts

- Consider the relationship between concepts, dimensions, and indicators

- Understand the method of concept mapping

What is conceptualization?

Concepts are the building blocks of theories. Concepts are “names for things, feelings, and ideas generated or acquired by people in the course of relating to each other and to their environment."1 Creating concepts is one of the first steps to engaging with the world. The process of conceptualization calls for the powers of observation and imagination. A political scientist might observe that all groups of people abide by authority, and that authority looks different across different groups of people. That might lead to the conceptualization of “regime,” or the organization of political authority across different societies. Or a political theorist might imagine that it’s possible to organize a political authority for all of humankind. That might lead to the conceptualization of “global government.” In other words, conceptualization is a process of naming things in the world, either observed or imagined (or sometimes a mix of the two), and using language to communicate those names, or concepts.

Political thinkers have long sought to conceptualize political authority, beginning with early philosophers such as Aristotle. In Politics, Aristotle begins by conceptualizing aspects of political life such as citizenship and the state. He asserts, “He who has the power to take part in the deliberative or judicial administration of any state is said by us to be a citizens [sic] of that state; and, speaking generally, a state is a body of citizens sufficing for the purposes of life.”2 After noting these building blocks of political life, Aristotle then wonders about the many ways in which citizens and states are organized. He muses,

“We have next to consider whether there is only one form of government or many, and if many, what they are, and how many, and what are the differences between them. …Governments which have a regard to the common interest are constituted in accordance with strict principles of justice, and are therefore true forms; but those which regard only the interest of the rulers are all defective and perverted forms, for they are despotic, whereas a state is a community of freemen.

“Having determined these points, we have next to consider how many forms of government there are, and what they are; and in the first place what are the true forms, for when they are determined the perversions of them will at once be apparent. The words constitution and government have the same meaning, and the government, which is the supreme authority in states, must be in the hands of one, or of a few, or of the many. The true forms of government, therefore, are those in which the one, or the few, or the many, govern with a view to the common interest; but governments which rule with a view to the private interest, whether of the one or of the few, or of the many, are perversions.”3

Aristotle, writing from a place of observation but also imagination, offers foundational concepts for understanding political life: citizens, states, and varieties of government. A shorthand term for the concept “varieties of government” that we use today is “regime.”

For Aristotle, the key variation in political authority is whether government (or regime) comprises one, a few, or many leaders. Second, he considers in whose interest that government is ruling, a narrow or broader constituency. By conceptualizing government in this way, Aristotle is making some important moves. He is asserting that there are two salient dimensions to regime, the size of the ruling group and in whose interest, they are ruling. Table 5.1 summarizes the types of government (regime) identified by Aristotle.

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\): Aristotle’s forms of government (regime types)

| |

Ruling in whose interest |

|

| Number of Rulers |

Common interest |

Private interests of one or the few |

| One |

Kingship |

Tyranny |

| Few |

Aristocracy |

Oligarchy |

| Many |

Polity |

Democracy |

In short, concept building is determining, to the best of our ability, precise language for observations and ideas that we believe are important for understanding social life. Concepts are the building blocks for theory and theory testing.

Dimensions and indicators

The brief foray into Aristotle’s conceptualization of political authority reveals two additional important aspects of concept building: dimensions and indicators. Concepts, especially the complex ones that are foundational in the study of human behavior, often have many dimensions. After identifying a concept such as “forms of government” (hereafter “regime”), concept building involves further thinking about underlying variation in that concept. Regime type, for example, might be thought of in Aristotelian terms: how concentrated political authority is in that society (e.g., in one, a few, or many leaders). Another dimension of regime may be how leaders are selected, regardless of their number. Yet another dimension, considered by Aristotle, is whether leaders serve public or private interests.

These are all dimensions of the same single concept, regime. Consider another important concept in politics, prosperity. There are many dimensions to this concept. One dimension may be the amount of wealth in a society. Another dimension might be how healthy a society is. Another dimension may be how equally goods are distributed in a society. Yet another dimension may be stability in the wealth enjoyed by members of a society. And so forth. Note that there exist many possible measures for each dimension of prosperity, a topic that will be taken up in section 5.3.

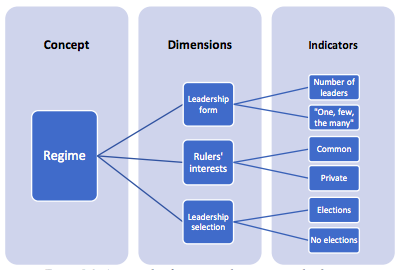

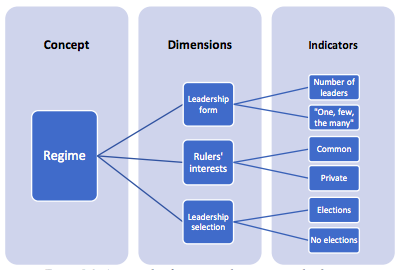

Indicators are more concrete aspects of dimensions. They are more specific and are often what we observe in the world around us. Continuing the example of regime, Aristotle and observations of the contemporary world suggests three dimensions to this concept: how leadership is structured, how that leadership rules over society, and how that leadership is selected. Aristotle suggests one indicator for the structure of different regimes: when there is one, a few, or many rulers. More generally, another indicator of this dimension might be the specific number of rulers in a government. In the United States, the number of elected rulers in federal government is 537, or 535 legislators, one president, and one vice president. Today, regime is also understood in terms of whether public office holders are selected via elections. This dimension of regime is leadership selection, and one indicator of this is the presence or absence of elections. Recall the discussion of variables in Chapter 4 and note that dimensions and indicators can be variables.

Concepts, dimensions, and indicators relate to one another in terms of their level of abstraction and how many may be nested within the other. Concepts are building blocks and foundational for scholarly inquiry. They are often abstract, for example the concept of “regime” as a way of naming and thinking about political authority. Dimensions are less abstract, and there may be many dimensions to a concept. Indicators are the most concrete, and there may be many indicators for a single dimension of a concept. Figure 5.1 below sums up how we might think about the concept of “regime”, related dimensions, and possible indicators of those dimensions.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): An example of a concept, dimensions, and indicators

Concept mapping

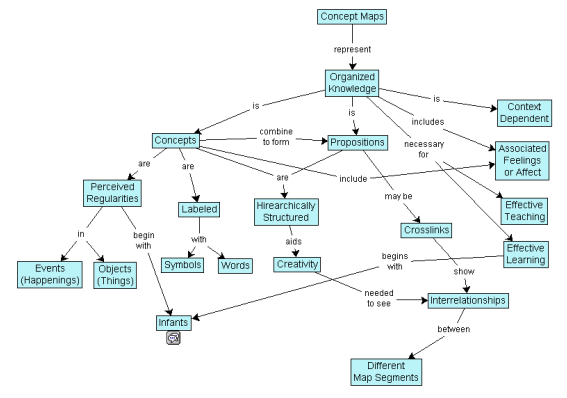

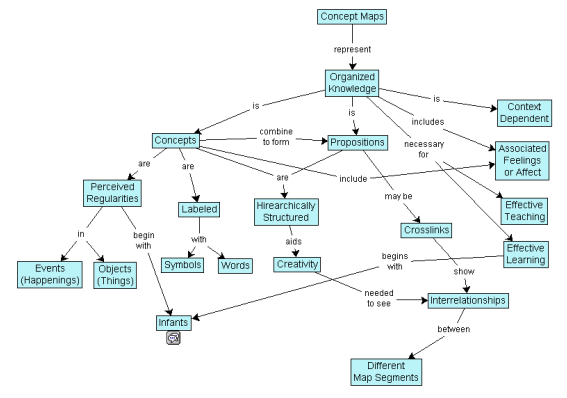

Concept mapping is a method for identifying concepts, dimensions and indicators, and their relationships to each other. Concept mapping can help with formulating a research topic and eventually a research question. It is a means to place concepts in a visual way such that one has a pictorial understanding of relationships between concepts, dimensions, and indicators. Concept mapping can be done by individuals or groups. Creating a concept map entails several conventions.

First, key concepts are usually enclosed in boxes or circles on a concept map. Another alternative is writing concepts on slips of paper to move them around the concept map. If a researcher wanted to create a concept map around the question, “What are the consequences of different regime types in the world?” they might first start by putting the word “regime” in a box at the top of the mapping space. Other related concepts, such as “conflict” and “prosperity” and “power” might also go in boxes on the map.

Second, concept maps are spatially organized from top to bottom, with more general concepts at the top of the mapping space (anything from a piece of paper to a wall-sized whiteboard) to more specific concepts at the bottom.

Third, lines or arrows are used to connect related concepts. If the researcher wants to explore the relationship between “regime” and “leadership form”, they might put those two phrases in circles and then connect those circles with a line and the words “according to Aristotle, determined by”. Another line might connect “regime” and “private interest” with “is perverted when rulers rule in the”. Figure 5.2 below offers an example of a concept map created using a computer program.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): An example of a concept map created using the IHMC CmapTools computer program by Vicwood40, CC BY-SA 3.0

Concept maps are a useful tool for visually depicting the scope of one’s knowledge on a central concept, relationships between that concept and relevant concepts, dimensions, and indicators.

Concept maps can also reveal how knowledge is organized and gaps in knowledge (i.e., areas for research). Concept mapping is distinct from other activities such as brainstorming because there are specific conventions how concept maps are drawn and how space is utilized in a concept map. Brainstorming can be a more general way to jot down concepts which are related to each other, but there are no conventions in brainstorming for how to organize concepts visually.

1 Hoover, Kenneth and Todd Donovan. 2011. The Elements of Social Scientific Thinking. Tenth Edition. Wadsworth Cengage Learning, p. 12.

2 Aristotle. 350 BCE. Politics. Book 3, Part I. Trans. Benjamin Jowett. Available online at http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/politics.html.

3 Ibid. Book 3, Parts VI and VII.