8.3: So, What Does the Governor Actually Do?

- Page ID

- 129182

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

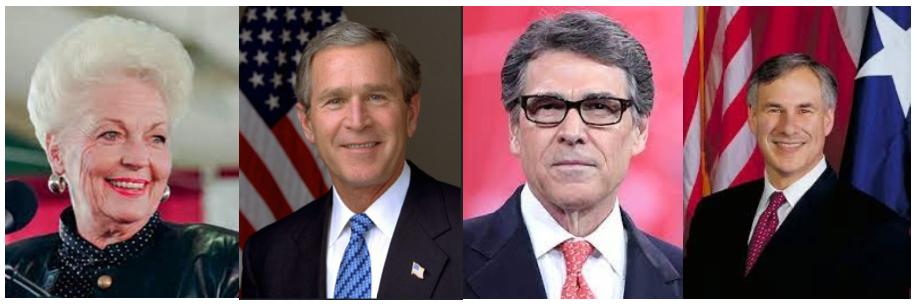

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Texas governor has many formal powers including executive, judicial, legislative, as well as the many informal powers which are embodied in the various roles that make up the office of chief executive for the state, including chief of state, chief intergovernmental diplomat, and chief administrator. The personality of the governor and the political, social, and economic circumstances that prevail during a governor's administration largely determine which roles are emphasized (Figure 8.11).

Executive Powers

News stories frequently describe the governor as the "chief executive," a role that refers to gubernatorial control over the stare bureaucracy and the governor's powers of appointment and removal, as well as budgeting, planning, supervisory, and clemency powers. Although the governor's role as the chief executive is one of the most time-consuming roles, it traditionally has been one of the weakest.

Appointment Powers The governor’s appointment powers are a crucial part of his executive powers. Texas has a long ballot because a large number of state officials, including many in the executive branch, are elected by the people rather than appointed by the governor. The list of officials elected on a statewide basis includes the lieutenant governor, whose primary role is legislative: the attorney general; the comptroller of public accounts; the commissioner of the General Land Office; and the agriculture commissioner. In addition. members of the Texas Railroad Commission and the State Board of Education, two powerful bodies, are elected. Because they are elected independently, they owe no allegiance or any obligation to the governor. Lacking direct influence on these elected officeholders, the governor must be highly skilled in the art of persuasion.

One of the most significant executive powers of the Texas governor is appointment power. Appointments allow the Governor to place allies in strategic locations in state government this is a critical asset in his or her efforts to establish and carry out policies. Governors can also use the appointment power to reward political supporters, a practice known as patronage.

The governor's appointment power is limited by the requirement that two-thirds of the Senate confirm appointments. The most visible executive appointments that the governor makes are those of secretary of state, commissioner of education, commissioner of insurance, commissioner of health and human services, and the executive director of the Economic Development and Tourism Division. In addition, the governor appoints the director of the Office of State-Federal Relations and the adjutant general (who heads the state militia). The governor makes several other appointments that are less prominent but nonetheless are of interest to those who fall within the jurisdiction or service areas of these bodies. These appointments are also useful channels of political patronage. Some examples are the Office of State-Federal Relations, the Office of Housing and Community Affairs, the Texas Film Commission, and the Texas Music Office. Unlike most other agencies in the executive branch, the Governor exercises direct authority over these offices. When a vacancy occurs in one of the major elected executive positions, the governor appoints someone to serve in the office until the next election. The governor also appoints all or some of the members of about two dozen advisory councils and committees that coordinate the work of two or more state agencies.

Most state agencies are not headed by a single executive who makes policy decisions. The result is a highly fragmented executive branch in which power is divided among both elected executives and appointed boards. Nevertheless, the governor has a major effect on state policy through approximately 1500–3000 appointments to more than 100 policymaking, multimember boards and commissions. Examples include the University of Texas System board of regents of higher education institutions, the Public Utility Commission, and the Texas Youth Commission. Because Rick Perry was governor for fourteen years, he was able to make over 8000 appointments! Fun fact: twenty-five percent of these were campaign donors.

The governor also uses the appointment power to fill vacancies in the judiciary. Although Texas has an elected judiciary, every legislature creates some new courts, and vacancies occur in other courts. The governor is authorized to make appointments at the district court level and all other upper-level courts. Appointees to these benches serve until the next election. Indeed, many of these judges in the state are first appointed and subsequently stand for election.

The governor must obtain a two-thirds confirmation vote from the Texas Senate for appointments. In addition, senatorial courtesy (the Senate's tradition of honoring the objection of a senator from the same district as the nominee) applies. Texas's short biennial legislative session, however, permits the governor to make many interim appointments when the legislature is not in session. This practice allows some appointees to serve for as long as nineteen months without Senate confirmation. Appointments made while the legislature is in recess must be presented to the Senate within the first ten days of the next session, whether regular or special.

Another aid to the governor is incumbency. A governor who is reelected is able to appoint all members of numerous boards or commissions who serve staggered six-year terms by the middle of the second term and perhaps earlier if some members resign. The governor may then have considerable influence over policy development within the agency, even though there may be little time left in the governor's term.

Single Executive Appointments Four important agencies headed by a single appointed executive are the office of secretary of state, the Health and Human Services Commission, the Office of Suite-Federal Relations, and the adjutant general. In addition, there are at least thirteen other state agencies headed by individuals appointed by the governor. These agencies, led by executive directors, arc less well known and serve less important functions. Among these agencies are the Department of Commerce, the State Office of Administrative Hearings, the Insurance Commission, the Department of Housing and Community Affairs, and the Public Utility Commission Council.

The beginnings of the Health and Human Services Commission date back to the Great Depression when the state legislature in 1939 established the new Department of Public Welfare. The department was composed of three members appointed by the governor for six-year terms; the governor also appointed an executive director to serve as chief administrative officer of the department. The major duties of the department were to administer the state laws regarding assistance to the needy, the aged. persons with disabilities, and dependent children and to carry out the state's child welfare program. The department was also charged with responsibility for protecting all children from abuse, neglect, or exploitation, licensing child-care and child-placing facilities, and providing adoptive services.

In 1977 the legislature changed the name of the department to the Texas Department of Human Resources. The department was restructured in 1980, with the programs categorized to reflect two major client groups: families and children, and aged and persons with disabilities. In 1985 the Department of Human Resources was renamed the Texas Department of Human Services.

The legislature authorized a new Health and Human Services Commission in 1992 to oversee the state's eleven human services agencies. Besides the Texas Department of Human Services, these agencies include the Texas Department of Health, the Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation, the Texas Rehabilitation Commission, the Texas Commission for the Blind, the Texas Commission for the Deaf and Hearing Impaired, the Texas Youth Commission, the Texas Juvenile Probation Commission, the Texas Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse, the Texas Department on Aging. and the Interagency Council on Early Childhood Intervention Services. The Child Protective Services, Adult Protective Services, and Childcare Licensing programs were subsequently transferred to the new Texas Department of Protective and Regulatory Services.

The Texas Office of State-Federal Relations (OSFR) was established in 1965 as a division of the governor’s office and became a separate agency in 1971. The governor appoints the executive director of the agency, subject to approval by the Senate. The governor, lieutenant governor, and speaker of the House serve as OSFR's Advisory Policy Board and set the agency's legislative agenda at the federal level.

Texas officials understand that in order for the state government to maintain a strong position in its relationship with the federal government, Texas must maintain an active presence in Washington, DC. Therefore. OSFR's mission is to promote communication and build relationship; between the state and federal governments and to advance the interests of the people of the state of Texas.

The major goal of the OSFR is to increase the influence of the governor and the state legislature over federal action that has a direct or indirect economic, fiscal, or regulatory impact on the state and its citizens, maintaining an active role for Texas in the national decision-making process. OSFR achieves these aims by working with the governor's office, the legislature, and state agencies to coordinate a federal agenda for the state of Texas; working with the U.S. Congress, the administration, and federal agencies to pass and implement legislation and rules favorable to Texas; and providing information to Texas officials about federal initiatives and helping them influence those initiatives.

The predecessor to the Adjutant General's Department existed under the Republic of Texas, but it was abolished in 1840, then reestablished as a state office in 1846. When it was reestablished, its activities were limited to the verification of veterans' land claims. The office operated intermittently from 1846 until 1905, when it was established by the Texas legislature. The adjutant general, who heads the Adjutant General's Department, is appointed by the governor for a two-year term. Two assistant adjutants general are also appointed by the governor upon recommendation of the adjutant general. All three officials must have previous military

service and at least ten years’ experience as commissioned officers in an active unit of the Texas National Guard.

The adjutant general serves as the governor's aide in supervising the military department of the state. Responsibilities of the Adjutant General's Department, which is located at Camp Mabry in Austin, include providing military aid to state civil authorities and furnishing trained military personnel from the state's military forces—the Texas State Guard, the Texas Array National Guard, and the Texas Air National Guard—in case of national emergency, civil unrest, or war. The office's annual working budget exceeds $14 million.

Multimember Board and Commission Appointments In addition to elected and appointed officials, the governor appoints over 2,800 individuals who serve on over 300 policy-making and governing boards, commissions, and other agencies that conduct day-to-day operations of the state. Multimember boards or commissions head most state administrative agencies and make overall policy for them. These boards appoint chief administrators or heads to handle the responsibilities of the agencies, including the budget, personnel, and the administration of state laws and those federal laws that are carried out through state governments. The boards and commissions have historically demonstrated a great amount of independence and autonomy. Two of the Texas state boards and commissions—the Texas Railroad Commission and the State Board of Education—have elected members.

Established by the state legislature in 1891, the Texas Railroad Commission (TRC) (Figure 8.12) has been historically one of the most important regulatory bodies in the nation because it strongly influenced the supply and price of oil and natural gas throughout the United States for much of the twentieth century. The commission was originally established to oversee railroads, including jurisdiction over rates and operations of railroads, terminals, wharves, and express companies. After 1894, when the legislature made the agency elective, the three commissioners have served staggered six-year terms. The Railroad Commission also includes over 1,000 employees.

Despite the fact that the federal Interstate Commerce Commission preempted the regulation of interstate transportation, the TRC was successful in restraining intra-state freight rates. While continuing to regulate intrastate railroads, the commission added buses and trucks to its transportation responsibilities. Its importance to the state and nation, however, has rested on its authority over the energy industry. In 1917, the legislature granted the TRC the authority to see that petroleum pipelines remained "common carriers" (meaning that they did not transport an individual or entity's oil or gas to the exclusion of others). Over the next twenty-five years, the TRC gained responsibility for enacting well-spacing rules, accepted jurisdiction over gas utilities, oversaw an enormous expansion of commission activity during the 1920s, and won the authority to prorate, that is, to set the rate at which every oil well in Texas might produce. This latter power enabled the TRC to simultaneously support oil prices and conserve the state's resources.

While its influence over oil has declined somewhat, the commission's responsibility for natural gas has greatly expanded. Because gas has traditionally been considered to be of lower value than oil, however, commission policies in this area were less developed and of less interest within the industry and to outsiders, but only until the 1930s and 1940s, when measures were taken to preserve the state's natural gas by forcing producers to return gas to reservoirs (instead of "flaring," or wasting it) and sustain reservoirs' pressure. Gas acquired considerable importance again in the 1970s. Although the commission's involvement in oil policy has drastically declined, it remains an important actor on the national energy stage. The commission also regulates all mining of coal and uranium and intrastate trucking, responsibilities that give the commission tremendous political clout in the state.

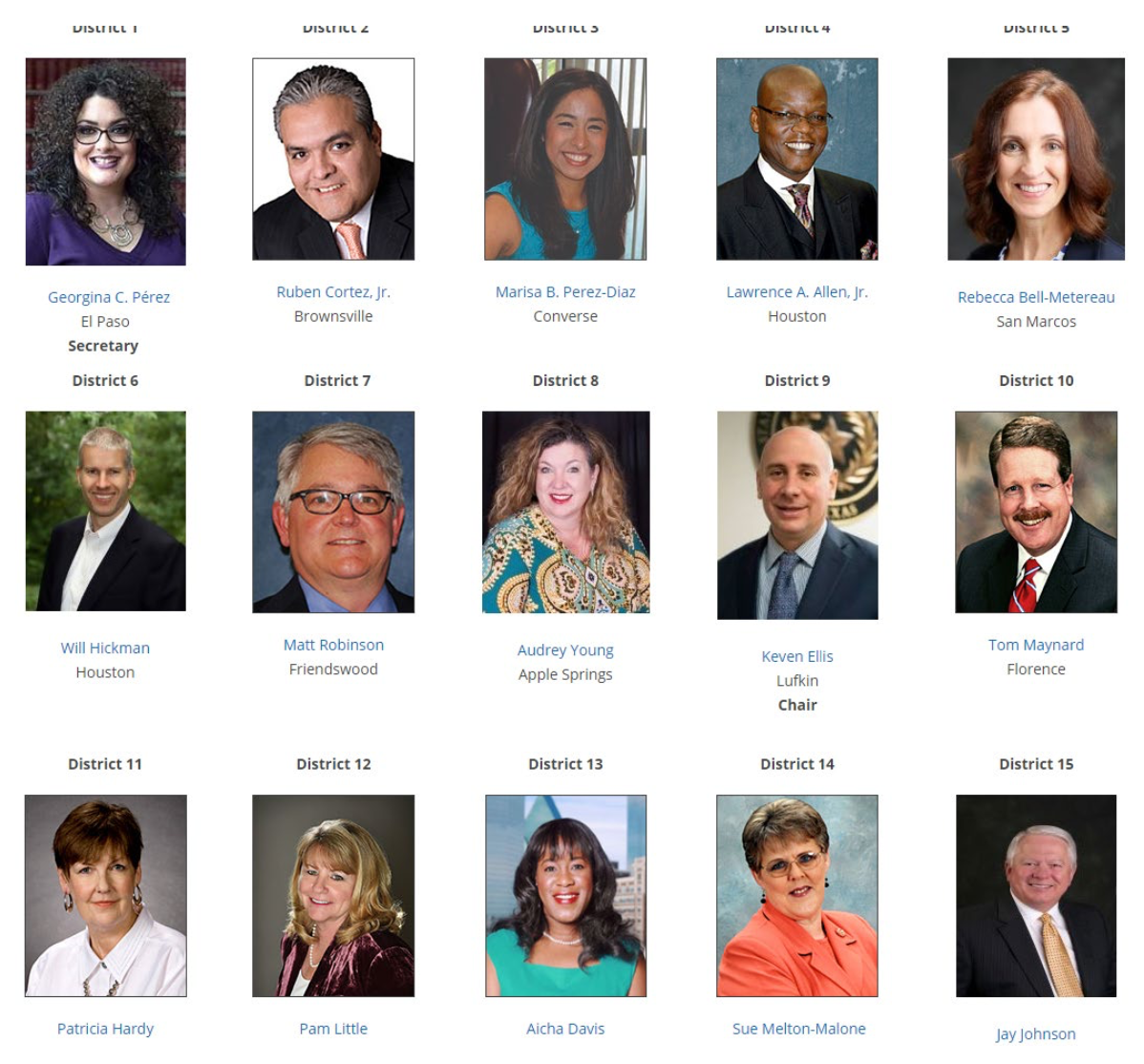

The State Board of Education (Figure 8.13) is responsible for setting the goals, adopting the policies, and establishing the standards for educational programs in the Texas public school system. The State Board of Education was originally created as an elected body but was made an appointive hoard as part of the public-school reforms of 1984. In 1987, voters overwhelmingly approved returning it to elective status. A majority of the board's current members are conservative Republicans, a fact that has reintroduced a longstanding political controversy about the board's selection of textbooks and curriculum (especially for biology and health classes) for public schools.

The commissioner of education serves as chief executive officer of the board. The commissioner is also the leader of the Texas Education Agency (TEA) and in that role supervises the administration of hoard rules. Together the hoard, the commissioner. and the TEA facilitate the operation of Texas's vast public school system consisting of over 1,200 school districts and charter schools. HIM e than 7,900 campuses, more than 590,000 educators and other employees, rind more than 4.5 schoolchildren.

The board designates and mandates instruction in the knowledge and skids that are essential to a well-balanced curriculum and approves and determines passing Scores for the state-mandated assessment program. lt also oversees the investment of the Permanent School Fund, approves the creation of charter schools, and adopts regulations and standards for the operation of adult education programs provided by public school districts, junior colleges, and universities.

Although policy decisions must be made by the full board, much of the preliminary work is done in committee sessions during which members of three standing committees—Instruction, School Finance/Permanent School Fund, and School Initiatives—consider items listed in the board agenda for the scheduled business meeting and review staff progress reports of work under way, proposals for new pro-grams, and suggestions for improving current efforts. The Committee on Instruction addresses issues concerning curriculum and instruction, student testing, vocational and special education programs, and alternatives to social promotion. Primary responsibility for issues dealing with school finance, vocational and special education programs, and the Permanent School Fund rests with the Committee on School finance/Permanent School Fund. The Committee on School Initiatives deals with issues such as charter schools, the long- range plan for public education, and rules proposed by the State Board of Educator Certification. In November 2020, the Texas State Board of Education made its first changes to its sexual education in twenty-three years but its new changes still fail to address identity and orientation by neglecting the LGBTQIA community.

Removal Powers Texas governors have limited removal power. They can remove political officials they have appointed, but only with the consent of the Senate. They can also remove personal staff members and a few executive directors, including the director of the Department of Housing and Community Affairs. However, governors cannot remove members of boards and commissions who were appointed by their predecessor or state executives who have been independently elected. This lack of removal power deprives the governor of significant control over the bureaucrats who make and administer executive policy and makes the governor's job of implementing policies through the state bureaucracy more difficult.

There are three general methods for removing state officeholders: impeachment, which involves a formal accusation—impeachment—by a House majority and requires a two-thirds vote for conviction by the Senate; address, a procedure whereby the legislature issues a request, after a two-thirds vote of both Houses, to the governor to remove a district or appellate judge from office; and quo warranto proceedings, legal procedures whereby an official may be removed by a court. Since Article 15 of the Texas Constitution stipulates the right to a trial before removal from office, impeachment is likely to remain the chief formal removal procedure because it involves a trial by the Senate.

Budgetary Powers Ok, so the Texas governor does not draft the budget, that is the job of the comptroller of public accounts. But the governor does submit a budget message that outlines revenue needs to the legislature at the beginning of the regular legislative session. By law, the governor must submit a biennial budget message to the legislature within five days after that body convenes in regular session. Prepared by the governor's Division of Budget, Planning, and Policy, the budget indicates to the legislature the governor's priorities and signals items likely to be vetoed. With the exception of the item veto, the Texas governor lacks the strong formal budgetary powers possessed by many state executives. One additional financial power held by the governor is the ability to approve deficiency warrants of no more than $200,000 per biennium for agencies that encounter financial emergencies or exhaust their funding before the end of the fiscal year.

Traditionally, the Legislative Budget Board (LBB), which also prepares a budget for the legislature to consider, has dominated the budget process. The legislature always has been guided more by the legislative budget than by the one devised on behalf of the governor.

Planning Powers Both modem management and the requirements of many federal grants-in-aid emphasize regional planning, usually by county or municipal governments., and the governor directs planning efforts for the state through the Budget, Planning, and Policy Division. When combined with budgeting, the governor's plan-fling power allows a stronger gubernatorial hand in the development of the state's new programs and policy alternatives. Although still without adequate control over some state programs. the governor has had a greater voice in suggesting future programs over the past two decades. mainly because many federal statutes designated the governor as the position empowered to approve federal grants.

Supervisory Powers The state constitution charges the governor with the responsibility for seeing that the laws of the state are "faithfully executed" but provides few tools to assist in fulfilling this function. The governor's greatest supervisory and directive powers occur in the role of commander in chief. Governors can request reports from state agencies, appoint hoard chairs, remove their own appointees, and use political influence to force hiring reductions or other economies. But lack of appointment power over the professional staffs of state agencies and lack of removal power over a predecessor's appointees limit the governor's ability to ensure that the state bureaucracy performs its job.

The governor thus must resort to informal powers to exercise control over the administration. In this respect, the governor's staff is of supreme importance. Staff members who can establish good rapport with state agencies may extend the governor's influence to areas where the governor does riot have formal authority. The governor's leadership of the party and the veto power two important factors that help staff perform this task.

Military and Law Enforcement Powers Can Texas make treaties or go to war with another country? No, the state of Texas does not independently engage in warfare with other nations so it might seem like there is no need for a commander in chief. However, the governor has the power to declare martial law—that is, the power to suspend civil government temporarily and replace it with government by the state militia and/or law enforcement agencies, although this power is seldom used.

The governor is also commander in chief of the military forces of the state (Army and Air National Guard), except when they have been called into service by the national government. The head of these forces, the adjutant general, is one of the governor's important. appointees. The governor also has the power to assume command of the Texas Rangers and the Department of Public Safety to maintain law and order. These powers become important during natural disasters or civil unrest. In addition, following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001, the national government created the Department of Homeland Security and mandated security responsibilities for state and local governments in addition to their traditional function of disaster management. The Texas homeland security office, the Division of Emergency Management, reports to the governor, but is operationally attached to the Texas Department of Public Safety.

Governor Abbott has been utilizing the National Guard to vaccinate homebound seniors and address the problems at the border. Recently Greg Abbott sent 1,100 National Guard troops to vaccinate seniors who could not get to facilities to receive the COVID 19 vaccine. This initiative is part of a project called “Save our Seniors.”

The National Guard has also been mobilized to address the mounting concern over unauthorized migrants entering Texas at the southern border. On Saturday March 6, 2021 Gov. Abbott launched “Operation Lone Star.” According to a reporter at KFOX14, “The Operation integrates DPS with the Texas National Guard and deploys air, ground, marine, and tactical border security assets to high threat areas to deny Mexican Cartels and other smugglers the ability to move drugs and people into Texas.”6 The longstanding complex problem of immigration is compounded by the overcrowding of the detention facilities. Oklahoma senator James Lankford tweeted that the detention centers which are designed to hold only eighty people are currently holding 709!7

Judicial Powers

The governor’s power with regard to acts of clemency (acts regarded as merciful that typically involve leniency or moderation in the severity of punishment due) is restricted to one thirty-day reprieve—a stay of execution—for an individual sentenced to death. in cases of treason against the state (a rare crime), the governor may grant pardons, reprieves, and commutations of sentences with legislative consent. The governor also may excuse or reduce fines or bond forfeitures and restore driver's and hunting licenses. In addition, the governor has the discretionary right to revoke a parole or conditional pardon. Beyond these limited acts, the state's chief executive officer must make recommendations to the Board of Pardons and Paroles, which is part of the Department of Criminal Justice. Although empowered to refuse an act of clemency recommended by the board, the governor cannot act without its recommendation in such matters as granting full and conditional pardons, commutations, reprieves, and emergency reprieves.

As discussed earlier, the governor is able to use the appointment power to fill vacancies in the judiciary. In Texas judges are elected in partisan elections, but sometimes vacancies occur, and the governor then is able to appoint a judge until the next election, and with the power of incumbency behind them, well it increases the likelihood of reelection. The governor is authorized to make appointments at the district court level and all other upper-level courts.

Legislative Powers

Although the legislature tends to dominate Texas politics, the governor is a strong chief legislator who relies on three formal powers to fulfill this role: message power, session power, and veto power.

Message Power The governor may give a message—a formal means of expressing policy preferences—to the legislature at any time, but the constitution requires a gubernatorial message when legislative sessions open (known as the "State of the State" message) and when a governor retires. By statute, the governor must also deliver a biennial budget message. Other messages the governor may choose to send or deliver in person are often "emergency" messages when the legislature is in session. Messages also attract the attention of the media and set the agenda for state government. Coupled with able staff work, message power can he an effective and persuasive tool. In both 2003 and 2007. Governor Perry declared insurance rates and medical malpractice reform as emergency measures. an indication that he had not otherwise achieved his policy objectives. A governor also often communicates his or her intentions at meetings and social gatherings or through the media.

Session Power As previously discussed, the legislature can be called into special session by the governor only after the legislature's regularly scheduled 140-day regular session has concluded. Special sessions are limited to no more than thirty days, but a governor may call an unlimited number of such sessions.

The governor sets the agenda for special sessions, although the legislature, once called, may consider other matters on a limited basis, such as impeachment or approval of executive appointments. As the complexity of state government has grown. legislators sometimes have been unable to complete their work during the short biennial regular sessions. When they fail to complete enough of the agenda. they know a special session is likely. However, any governor contemplating calling a special session must consider whether he or she has collected the votes necessary to accomplish the purpose of the session.

As a result of the COVID 19 virus, there were delays in census information gathering, which has delayed redistricting in Texas in 2021. On February 12, 2021 the U.S. Census Bureau has announced that the population numbers that are used to draw the district lines and reflect the population growth over the past ten years will be not be ready until September 30, 2021. This delay will cause Governor Abbot to call a special session to address redistricting in Fall of 2021.8 Veto Power The governor's strongest legislative power is the veto. Every bill approved by both houses of the legislature in regular and special sessions is sent to the governor, who has the option of signing it, allowing it to become law without his signature. or vetoing it. If the legislature is in session, the governor has ten days—Sundays excluded—in which to act. If the bill is sent to the governor in the last ten days of a session or after the legislature has adjourned, the governor has twenty days—including Sundays—in which to act. If the governor does not sign the bill within those ten- or twenty-day periods, it automatically becomes law.

If the governor vetoes a bill while the legislature is still in session, the legislature may override the veto by a two-thirds vote of both Houses. However, because of Texas’s short legislative sessions, many important bills are often sent to the governor so late that the legislature has adjourned before the governor has had to act on them. In such instances, the governor's veto power is absolute because the legislature cannot override if it is not in session, and consideration of the same bill cannot be carried over into the next session. Short biennial sessions thus make the governor's threat of a veto an extremely powerful political tool. In addition, because an override of a veto requires a two-thirds vote in both Houses, they occur only rarely.

The governor has one other check over appropriations bills: the line-item veto. This device permits the governor to delete individual items from a bill without vetoing it in its entirety. The item veto may be used to strike a particular line of funding, but it cannot be used to reduce or increase an appropriation.

Informal Powers

In routine situations, the governor is almost wholly dependent on local law enforcement and prosecuting agencies to ensure that the laws of the state are executed. When evidence of wrongdoing exists, the governor often invokes the informal powers of the office, appealing to the media to focus public attention on errant agencies and officeholders. In the chapter opening, Governor Abbott uses social media (Twitter) to deride President Biden on his handling of the mass amounts of unaccompanied minors arriving from Mexico. He further has been using conservative media outlets like Fox News to draw more attention to this issue and the health concerns arising from it. In addition to the use of media, the governor plays a number of ceremonial roles invested with informal powers, including chief of state, intergovernmental diplomat, and chief administrator of the Texas bureaucracy.

Chief of State Pomp and circumstance are a part of being the top elected official of the state. Just as presidents use their ceremonial role to augment other roles, so do governors. Whether cutting a ribbon to open a new highway, leading a parade, or serving as host to a visiting dignitary, the governor's performance as chief of state yields visibility and the appearance of leadership, which enhance the more important executive arid legislative roles of the office. In the modem era, the governor is often the chief television personality of the state and sets the policy agenda through publicity.

Texas governors are more often using the ceremonial role of chief of state, sometimes coupled with the role of chief intergovernmental diplomat, to become actively involved in economic negotiations such as plant locations. Efforts are directed toward both foreign and domestic investments and finding new markets for Texas goods. In such negotiations, the governor uses the power and prestige of the office to become the state's salesperson. Texas has a cost of living below the national average, fewer restrictions, and no state income taxes so is it any wonder that many tech companies are moving to Texas. These include Tesla, Oracle, Hewlett Packard, Google, and many others.

Savvy governors use the chief of state role to maximize publicity for themselves and their programs, Because Texas is the second most populous state in the country, the actions of the Texas governor often make national as well as state headlines.

Chief Intergovernmental Diplomat The Texas Constitution provides that the governor, or someone designated by the governor, is the state's representative in dealings with other states and with the national government. This role of intergovernmental representative has increased in importance for three reasons. First, federal statutes now designate the governor as the official with planning and grant-approval authority for the state. This designation has given the governor's budgeting, planning, and supervising powers much greater weight in recent years.

Second, some state problems, such as water and energy development, often require the cooperation of several states. For example, Governor Clements and live other governors attempted to devise solutions for the water problems experienced in the High Plains area. Additionally, although the U.S. Constitution precludes a governor from conducting diplomatic relations with other nations, Texas's location as a border state gives rise to occasional social and economic exchanges with the governors of Mexican border states on matters such as immigration, energy, and the environment.

Third, acquiring federal funds is critical because national funding relieves the pressure on state and local government revenue sources. The Texas governor works with other governors to secure favorable national legislation, including both funding and limits on underfunded or unfunded federal mandates. Thus, Texas governors are active members of the National Governors Association and participants in the National Governor’s Conference. They must also be active in regional and political party groups.

A more traditional use of the governor's intergovernmental role is extradition, which is mandated by Article 4 of the U.S. Constitution. Article 4 provides for the rendition (surrender) of fugitives from justice who commit crimes in Texas and then flee across state lines to another state. The Texas governor signs the rendition papers and transmits them through the secretary of state to the appropriate law enforcement officials. Law officers are then responsible for capturing and securing the fugitives and returning them to the state.

Chief Administrator The Texas governor oversees the state's bureaucracy that executes and administers government policy. The governor usually appoints the agency head or members of the board or commission that oversees the agency and, for many agencies, also appoints the board chair. This power of appointment can greatly affect an agency's success or failure. A governor who is a skillful chief legislator can influence neutral legislators to look favorably on an agency and thus may help an agency get its budget increased or add a new program. As chief administrator, the governor can referee when an agency does not have the support of its clientele group and give an agency visibility when it might otherwise languish in obscurity.

6. Office of the Texas Governor / Greg Abbott, “Organization,” https://gov.texas.gov/organization.

7. Sen. James Lankford @senatorlankford, Twitter Post, Mar. 26, 2021, 1:49PM, https://twitter.com/senatorlankford/...59880723755014.

8. Alexa Ura, “Latest Census Delay Will Push Texas' Redrawing of Political Maps into the Fall,” Texas Tribune, Feb. 12, 2021, https://www.texastribune.org/2021/02...ecial-session/.