8.4: The Texas Bureaucracy

- Page ID

- 129183

As the national government expanded its programs and their associated costs throughout the 1970s, state and local governments grew rapidly to take advantage of available federal dollars for new programs, respond to mandatory federal initiatives, promote economic expansion, and develop new programs and services. Each new service increased the number of people necessary to keep the government functioning. In Texas. the combination of more programs and increased population resulted in an increase in the size and scope of state and local governments Texas has fewer employees per 10,000 people than the other states except in the category of corrections. In all the other major program areas—higher education, highways, hospitals and public welfare— Texas has fewer employees, those lower numbers do not signal greater efficiency. Rather they signal that Texans receive proportionately fewer government services than citizens to the other large states.

As the economy all across the country faltered during the 1990s, Texas's largely Anglo middle class became more concerned about the economy and its role in it than about social issues. Economic and political distance between the mainly white suburbanites and the basically minority lower economic class in the central cities increased. Because the lower class tends not to vote, governments at all levels tended to listen to the suburbanites, a phenomenon that resulted in more attention to accountability. greater demands for tax ceilings and spending cutbacks, and increased emphasis on economic development and less on the welfare state. However, major problems that only government could address remained—crime, environmental pollution, and the educational system, for example. Moreover, the national government began to impose requirements such as clean air and water upon the states in the form of mandates. The states in turn passed problems and mandates such as the need for better education to the local governments.

Consequently, state and local governments again increased in size, programs, and expenditures, much to the regret of many taxpayers, who preferred less government and an end to state and local tax increases.

The State of Texas is the state's largest single employer. Over seventy-five percent of Texas state employees work in five major areas: criminal justice, mental health and retardation, human services, transportation, and public safety. The structure and practices of the Texas bureaucracy reflect the general belief that state government should be decentralized. Unlike the employment systems of most states, Texas has no merit-based civil service system or personnel agency that assumes the responsibility of overseeing all human resources matters. Each agency, board, panel, or commission establishes its own rules and regulations regarding personnel.

The state prison system, which accounts for about one in five employees added to state payrolls since the late 1980s, is the fastest-growing employment sector in state government. Large and generally consistent employment growth in state government also occurred in the major health and human services agencies. The number of hospital workers, public welfare employees, and those who work with state and federal public assistance programs for the poor (such as Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, food stamps and Medicaid, immunization services, health inspections, and environmental pollution control) increased. Employment growth in higher education has also been consistent, but to a lesser extent. The remaining state agencies have grown at an average annual rate of less than four percent.

Because the administrators operate in the arena of political activities, they must rely on a number of individuals and groups who use political and other tactics to sustain themselves. Among these individuals and groups are the client groups with whom they share goals, personnel, information, and lobbying strategies; the legislature. upon whom agencies exert both direct and indirect influence; the governor, who is interested in protecting the interests, authority, and financial resources of the bureaucracy; the public, which provides some agencies with substantial public recognition and support: and agency leaders.

Accountability and Sunshine Laws

Freedom of information legislation, also described as open records laws, includes laws that set forth the rules on access to information or records held by government bodies. In general, such laws define the legal process by which government information must be made available to the public. Under the Texas Open Records Act. originally passed in 1973, the public, including the media, has access to a wide variety of official records and to most public meetings of state and local agencies. Sometimes called the Sunshine Law because it forces agencies to shed light on their deliberations and procedures, this act is seen as a method of preventing or exposing bureaucratic ineptitude, corruption, and unnecessary secrecy. An agency that denies access to information that is listed as an open record in the statute may have to defend its actions to the attorney general and before a court. In addition, the legislature also requires state agencies to write their rules and regulations in understandable language.

Closely related is open meetings legislation, which allows access to government meetings in addition to the records relating to those meetings. The 1987 Texas Open Meetings Act strengthened public access to information by requiring government bodies to certify that discussions held in executive sessions were legal or to tape-record closed meetings. The law generally provides that every regular, special, or called meeting of a governmental body, including city councils and most boards and commissions, must be open to the public and

comply with all the requirements of the act. There are seven exceptions that generally authorize closed meetings, also known as executive sessions. Closed meetings are permitted when sensitive issues such as real estate transactions or personnel actions are under consideration, but the agency must post an agenda in advance and submit it to the secretary of state, including what items will be discussed in closed session.

In 1999, the legislature strengthened open meetings provisions by placing firm restrictions on staff briefings that could be made before governing bodies at the state and local level. Two new types of exceptions emerged from the Seventy-sixth Legislature (economic development and utilities deregulation), but these were seen as protections on behalf of the public when a government was in a competitive situation. Thus, while Texas government became even more open following the 1999 session, governments were still permitted to hold closed meetings when competitive issues were the topic of discussion. In 2005, the Seventy- Ninth Legislature mandated that all public officials and members of all boards receive training in open government. Unfortunately, Sunshine week which lasts from March 14-20, was not as shiny as usual because the 2020-2021 COVID pandemic and the 2021 February freeze has served as an excuse for not releasing information to the public. The executive director of the Freedom of Information Foundation of Texas, Kelley Shannon questions, “Where are COVID-19 clusters occurring?”9 She asked in a recent blog post:

Are elderly loved ones safe? What’s the latest on COVID testing and vaccine distribution? How are taxpayer dollars being spent on pandemic aid in our communities? The Texas Public Information Act is supposed to help us answer these questions of life and death and following the money. But in many cases, governments are using the pandemic itself to ignore them.10

Sunset Legislation

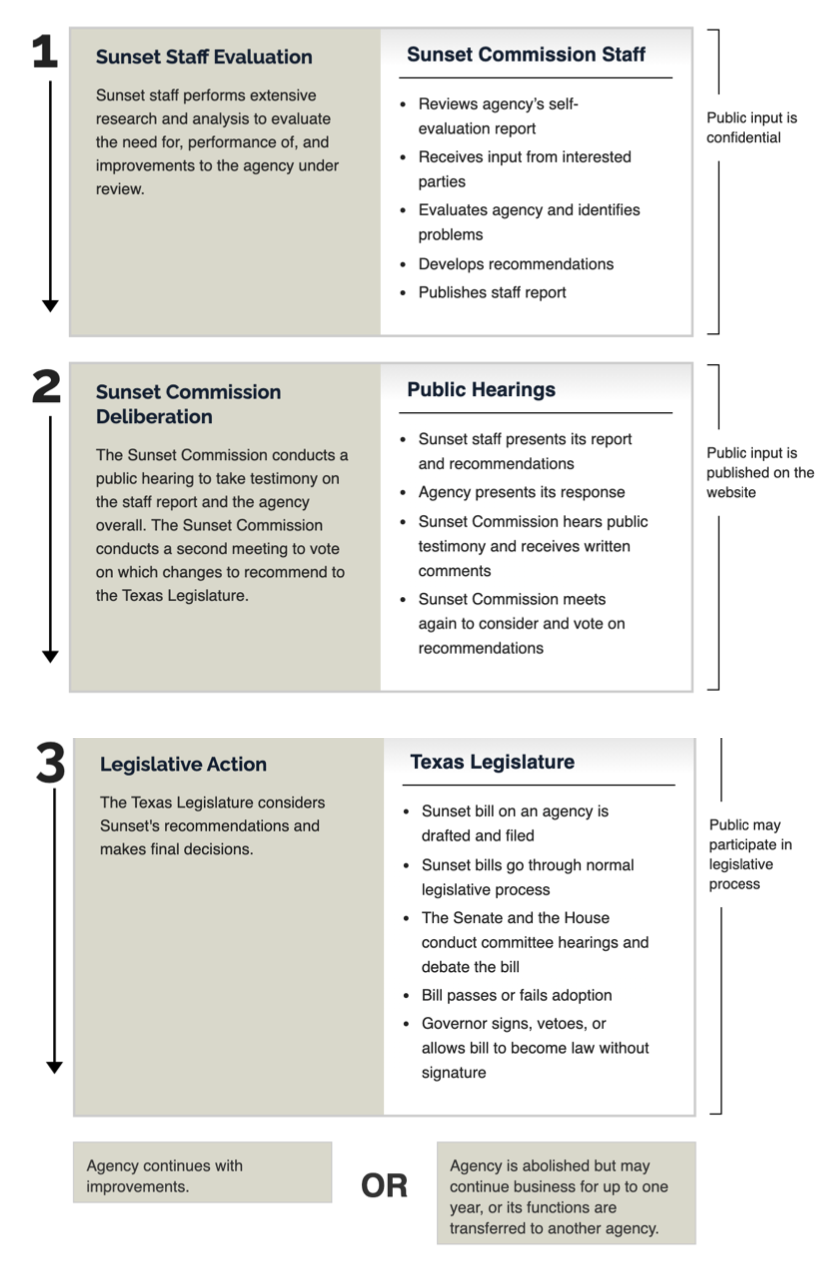

With the passage of the Sunset Law by the Sixty-Fifth Legislature in 1977, Texas established a procedure for legislative oversight by allowing the legislature to evaluate more than 150 state agencies, boards, commissions, and departments on a periodic basis (usually every twelve years). These sunset reviews are conducted by a twelve-member Sunset Advisory Commission composed of five senators and five representatives appointed by their respective presiding officers, who also appoint two citizen members each. The chairmanship rotates between the House and the Senate every two years. The Texas Sunset Advisory Commission (TSAC) determines the list of agencies to be reviewed before the beginning of each regular legislative session. The TSAC's 2008-2009 agenda includes a mixed bag of forty general government, health and human services, public safety and criminal justice, business and economic development, and regulatory licensing agencies and programs. The following is a flow chart (Figure 8.14) which illustrates how sunset works.

The agencies must submit self-evaluation reports that recommend improvements in efficiency and effectiveness, and the TSAC coordinates its information gathering with other agencies that monitor state agencies on a regular basis, such as the Legislative Budget Board, legislative committees, and the offices of the state auditor, governor, and comptroller. The TSAC also conducts public hearings, during which it questions the need for each agency, looks for potential duplication of other public services or programs, and considers new and innovative changes to improve each agency's operations and activities. Following the hearing, the legislature may recommend that an agency continue, reorganize, or merge with another agency.

If the Sunset Commission takes no action, the "sun sets" on the agency and it ceases to exist. In some cases, an agency's responsibilities or jurisdiction is transferred to another agency that has demonstrated good performance. Since the first sunset reviews, over fifty agencies have been abolished, and at least ten other agencies have been consolidated.

Suggested Reforms

A number of legislators and other elected officials have suggested that Texas should attempt to reduce state government employment levels and curb future growth, Researchers of state government growth trends have recommended that the Texas legislature should cap employment in executive branch agencies and institutions of higher education and reduce the number of managers and supervisors through attrition. The reduction in higher-paid personnel would result in a reduction of the agency's expenditures and future budgets. Others urge that that employment levels at the state's bureaucratic agencies should be allowed to grow at a rate no faster than that of the agency's client population. When the legislature authorizes a new program or reassigns programs to other agencies, the additional employees needed to administer those programs

would be added to the administering agency's cap. Reformers also recommend that all state agencies and institutions of higher education should implement a legislature-created uniform state payroll system in order to create consistent in salaries throughout the entire state bureaucracy.

Forecasters contend that implementing these and other minor changes to the existing system would maximize employee and agency productivity, increase the efficiency of the state bureaucracy. and result in an annual financial savings. Some critics charge, however, that enacting and applying these changes is unrealistic because the affected agencies will expend great effort to protect their power and interests. Bureaucratic agencies and their employees are motivated initially to substantiate their existence. Their subsequent desire to grow derives from their wish to maintain their positions, their genuine commitment to the programs administered by their organizations, and also perhaps their sincere concern for the people who benefit from their agency's programs.

Perhaps the most important suggestion for reform of the state bureaucracy is to create a cabinet-type government. Such a reorganization could consolidate more than 230 agencies into a series of executive departments that report to the governor. The only elected executives would be the governor and the lieutenant governor. This scheme, similar to the organization of the national government, would still leave the largest regulatory commissions—the Texas Railroad Commission to the Public Utilities Commission, and others—as independent agencies.

Reorganizing the bureaucracy would pose a great challenge because a major package of constitutional amendments and statutes would he required. The likelihood of such a sweeping change is small. especially in light of the many individuals and entities intent on preserving the status quo.

9. Kelley Shannon, “Opinion: In Pandemic Era, Texans’ Access to Public Information at Risk,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 8, 2021, https://www.statesman.com/story/opin...sk/4435895001/.

10. Kelley Shannon, “In Pandemic Era, Texans’ Access to Public Information at Risk,” Freedom of Information Foundation of Texas: Protecting the Public’s Right to Know, Feb. 5, 2021, https://foift.org/2021/02/05/in-pand...ation-at-risk/.