9.2: The Structure of the Texas Court System

- Page ID

- 129221

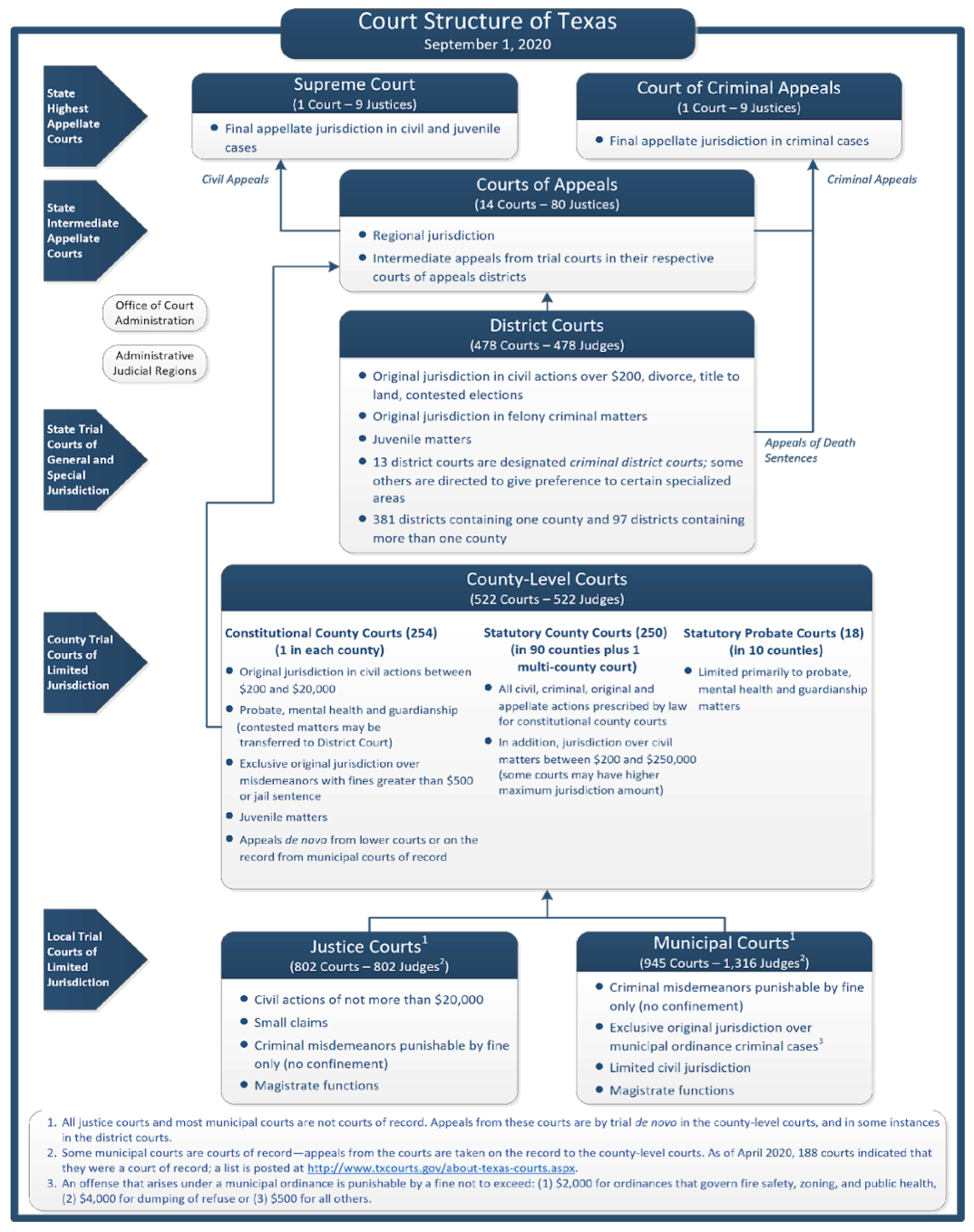

The Texas court system is hierarchical, meaning that cases originate in local trial courts, then proceed to other courts based upon how the courts are ranked—one above the other—according to their status or authority (Figure 9.4). Municipal, or city, courts address civil and criminal cases at the lowest level of the state’s court system. Justice (of the Peace) courts, constitutional county courts, statutory county courts, probate courts, and district courts are administered by the counties. All of the above courts are trial courts and generally exercise original jurisdiction. Beyond them are courts that exercise appellate jurisdiction. Those courts, composed only of judges or justices, are administered by the state, and include the courts of appeals, the Court of Criminal Appeals, and the Supreme Court of Texas. The figure below depicts the current structure of the Texas court system.

Trial Courts

There are no jury trials in Texas’s trial courts beyond the district courts, so a case is argued only before a panel of judges. A case in any court above the district court is argued only before a panel of judges. In civil cases, the parties are entitled to a jury trial when it is demanded by either party to the case and the demanding party pays a jury fee.14 If no party does either, the case will be tried before a judge only.

In criminal cases, a defendant is also entitled to a jury trial.15 The prosecutor, acting on behalf of the state, cannot take away a jury trial if one is desired by a defendant. However, a defendant can waive his or her right to a jury trial, but—in some cases—this waiver must be approved by the prosecuting attorney.16

Municipal Courts Municipal courts are city courts, often with judges appointed by mayors and city councils, which also determines their qualifications. They have exclusive jurisdiction over cases involving the violation of city ordinances, which are essentially laws passed by a city council or other governing body. Mostly, however, municipal courts handle parking and traffic tickets. Recent statistics indicate that over 5.5 million parking and traffic cases are heard in the municipal courts. In addition, these courts deal with over two million non-traffic misdemeanor cases per year. In each of these cases, the punishment is by fine only without the possibility of confinement.

County Administered Courts There are several types of county administered courts, including justice courts and county courts. County courts include constitutional, statutory courts, and statutory probate courts.

Justices of the Peace (JPs) are not required to be licensed attorneys, and a majority of them are, in fact, not lawyers. However, they are required to obtain eighty hours of continuing education during their first year in office and twenty hours annually thereafter. Justice courts, or JP courts, are county administered courts, and the number of these courts is determined by the number of people in each country. For example, Harris County has sixteen JP courts, two of which share jurisdiction in each of the county’s eight precincts. Every county has at least one JP court. JPs are the true jacks-of-all-trades in the Texas judicial system. They handle more serious offenses, like driving under the influence of alcohol, and other low-level criminal offenses, including disorderly conduct, criminal trespassing, and simple assault. They also handle civil cases (such as small claims cases) involving amounts up to $20,000, debt collection cases, commercial and residential evictions, and truancy. JP cases are appealed to the county court level. When this occurs, the appeal results in a trial de novo (a "new trial" by a different court). In criminal cases, cases beginning in justice court cannot be appealed beyond the county level court unless the fine is more than $100 or a constitutional matter is asserted.

Each of the 254 Texas counties is constitutionally required to have one constitutional county court. In the least populous counties, the constitutional county court judge fulfills the roles assumed by numerous judges in the most populous counties. For example, constitutional country courts have jurisdiction of:

- civil cases between $200 and 20,000;

- probate matters (involving wills and estates, guardianships and heirships, and matters

- involving a person who is suspected of being mentally ill and may pose a danger to him or herself, is incapable of taking care of him or herself, or may pose a danger to others);

- misdemeanors with fines greater than $500 or the possibilities of confinement;

- juvenile matters; and

- appeals de novo from non-record courts (courts whose proceedings are not recorded and therefore unavailable as evidence of fact).

These judges also assume the responsibilities allotted to statutory county court judges and statutory probate judges. In the more populous counties, the Texas legislature has created, through laws of a general and permanent nature, additional statutory county courts. The legislature has allowed counties specific numbers of these courts, depending on the county’s population. Over 200 of these statutory county courts, also known as a county courts at law, have been created in more than eighty densely populated counties to assist with the responsibilities that only one court and judge could not possibly handle alone. In the most populous counties, there exist both civil and criminal courts-at-law. County criminal courts-at-law can handle cases involving up to a year in county jail, and where the fine would exceed $500. Civil courts-at-law handle disputes involving between $20,000 and $100,000, as well as civil appeals from justice of the peace courts.

Statutory probate courts have been created by the Texas legislature to account for the vast number of people who live in the ten most populated areas of the state. These courts have jurisdiction over their respective counties’ probate matters (relating to wills and estates), guardianship and heirship cases, and mental health determinations and commitments. As previously mentioned, in less populated counties, these matters are handled by the local constitutional or statutory county court judges.

District Courts District courts represent the highest state courts where jury trials occur. District courts in rural Texas can be all-purpose courts—hearing all types of criminal and civil cases. District courts in urban areas often specialize. For example, in Harris County, with its population of almost 4.8 million, has courts specifically assigned only to criminal cases, with others specifically assigned to civil, juvenile, and family cases. District judges are elected in partisan elections and serve four-year terms. The most serious criminal cases and the highest dollar civil cases are tried in the district courts. If a felony is alleged in a criminal case, it must be tried in a district court to the exclusion of all other courts. This includes felony criminal cases in which a convicted person can receive state prison incarceration or the death penalty. In addition, civil cases involving more than $200 can be heard by district courts. It is important to note that because this amount of money also coincides with jurisdictional amounts of other courts in the state, those courts have what is known as concurrent jurisdiction. When this occurs, whoever brings the lawsuit can engage in “forum shopping,” a phenomenon that occurs when parties will try to have their civil or criminal case heard in the court that they perceive will be most favorable to them.

These courts also have exclusive jurisdiction over disputed land title cases, contested elections (e.g., when one candidate requests a post-election recount because the difference between number of votes received by the person bringing the lawsuit and number of votes received by the person elected is less than ten percent of the number of votes received by the person elected),17 and about seventy-four percent of the juvenile cases brought in the state. Divorces must also be resolved in district courts. As a result, district courts address a large volume of family law disputes which come before the courts for resolution. The issues not only include dissolution of marriages, but also the division of community property and debts, orders concerning possession and support of children, modification, enforcement of prior orders affecting children, and family violence and protective orders.18

Appellate Courts

Appellate courts include courts of appeals and the Texas Criminal and Texas Supreme Court.

These courts have jurisdiction to consider civil and criminal cases that are appealed from the lower district or county courts.19

Courts of Appeals Texas has fourteen courts of appeal located in thirteen geographic regions of the state. Each of these courts serves a specific set of counties. The judges who serve on these courts are called justices. The number of justices ranges from three to thirteen, one of whom is the Chief Justice, who serves as the administrative head of the court. Almost every county is located in a single court of appeals district. Justices are elected for six-year terms with an unbalanced staggering of terms in partisan elections. The terms are staggered so that approximately one-third of the positions on each court are considered by the voters who live in the region governed by that particular court of appeals for reelection every two years. Vacancies between elections are filled by the governor, who appoints a person to fill the vacancy with the advice and consent of the state Senate.

The caseload for courts of appeal in Texas is staggering. While the district courts from which a court of appeals’ appellate cases are referred may be highly specialized, the courts of appeals are not. In recent years, the fourteen courts of appeals have heard over 10,000 cases annually. For the sake of efficiency, nearly all cases are heard by multi-judge (usually three) panels, which are chosen immediately after an appeal is filed. This process allows the court to triple the number of cases it can consider at any one time. All fourteen courts have intermediate appellate jurisdiction over every type of criminal and civil case, with one exception. When the death penalty is giving to an accused in a district court, that case proceeds to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals rather than a court of appeals.

Recall that there are no jury trials in Texas’s trial courts beyond the district courts, so a case is argued only before a panel of judges. The appeals heard in these courts are based upon the “record” (a written transcription of the testimony given, exhibits introduced, and the documents filed in the trial court) and the written and oral arguments of the appellate lawyers. The courts of appeals do not receive testimony or hear witnesses in considering the cases on appeal, but they may hear oral argument by the attorneys on the issues under consideration. The courts of appeals both review the decisions of lower court judges and juries and evaluate the constitutionality of the statute or ordinance upon which the conviction was based. The outcome of an appeal is dependent upon whether an error occurred at the trial and, if so, whether that error resulted in an improper result. Decisions of the courts of appeals are usually final, but a small percentage of those decisions are reviewed by the two highest state courts.

Texas is one of only two states to utilize a bifurcated (split into two) appellate court system, meaning that the top-tier structure of the court system is divided into two courts whose exclusive jurisdiction focuses on appeals for criminal and civil cases. These two courts are not only responsible for reviewing the decisions made by lower courts judges and juries but also for interpreting and applying the state constitution. Therefore, the power of constitutional interpretation gives these courts the name of courts of last resort and provides them with vital judicial and political importance to the state. In addition, the courts publicly announce rules of appellate procedure and rules of evidence for civil and criminal cases and administer public funds are appropriated by the legislature for the education of judges, prosecuting attorneys, criminal defense attorneys who regularly represent indigent defendants, clerks and other personnel of the state’s appellate, district, county level, justice, and municipal courts.

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals is the highest court in the state that reviews criminal cases only, including automatic appeals on behalf of those convicted of felonies who receive the death penalty. The Chief Justice and remaining eight justices are chosen by partisan, statewide elections for staggered, six year terms. Vacancies between elections are also filled by the governor, who appoints a person to fill the vacancy with the advice and consent of the state Senate.

When a party loses at a lower court (usually when relief at a court of appeals is denied), he or she must file a petition for discretionary review to the Court of Criminal Appeals within thirty days. If the Court of Criminal Appeals grants a petition, it will schedule the case for oral argument and thereafter render its decision in the case. All nine members of the court are present for oral arguments.

Supreme Court of Texas The Supreme Court has statewide, final appellate jurisdiction in most civil and juvenile cases (Figure 9.5). The composition, structure, number of justices, method of election, term of office, and qualifications are identical to that of the Court of Criminal Justice and its members. Much of the Supreme Court’s time is spent determining which petitions for review will be granted, as it must consider all petitions for review that are filed. The Supreme Court exercises substantial control over its caseload in deciding which petitions will be granted. The Supreme Court usually takes only those cases that present the most significant Texas legal issues in need of clarification. However, the number of cases added to the Supreme Court’s docket has consistency increased.

In addition to the duties it shares with the Court of Criminal Appeals, the Supreme Court publicly announces rules of administration to provide for the efficient administration of justice in the state, monitors the caseloads of the courts of appeals and orders the transfer of cases among the courts in order to equalize the courts’ workloads, appoints the Board of Legal Examiners (which prepares and oversees the grading process of the State Bar examination), certifies successful applicants who are entitled to practice law in the state, and, with the assistance of the Texas Equal Access to Justice Foundation, administers funds for the Basic Civil Legal Services Program, which provides basic civil legal services to people who are indigent.

14. Tex. Const., art. I, § 10.

15. Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 1.13 (1965).

16. Texas Secretary of State, Procedures to Request and Conduct a Recount (2020), https://www.sos.state.tx.us/election...recounts.shtml.

17. Texas Divorce Statistics, SSJM Family Law (2021), https://www.kantlaw.com/texas-divorce-statistics/.

18. Paul Womack, “Judiciary,” https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/judiciary.

19. Personal Audio, LLC v. Apple, Inc., et al., No. 9:09-CV-00111-RC (E.D. Tex. 2010).