9.3: Texas Legal Process

- Page ID

- 129222

If you are a registered voter or hold a valid Texas driver’s license, the chance is very good that you will one day be called for jury duty by your county or district clerk. You will be asked to appear at the country courthouse on a specific day to make yourself available for jury service. You might be part of a jury for either a civil or a criminal proceeding. If, and when that happens, you should familiarize yourself with how either civil or criminal processes transpire.

Texas Civil Processes

The civil justice system is meant to be like a balanced scale, with neither side having any special advantage. The party bringing the civil suit—the complaining party—is the plaintiff. The party being sued is the defendant. In addition to the parties, civil cases also involve a number of players: judges, attorneys, lay and expert witnesses, jurors, local government clerks, court reporters, and bailiffs, among others.

The Texas Rules of Civil Procedure lay down the rules that govern civil actions. The rules are promulgated for a just, fair, equitable and impartial adjudication of the rights of litigants under established principles of substantive law by the state courts. Civil lawsuits can often take complex and unpredictable routes through the legal system, and many can proceed through as many as eight different stages before reaching a conclusion. For example, one of the biggest recent civil cases in Texas was Personal Audio of Beaumont, Texas, vs. Apple, Inc. Personal Audio, claimed Apple had stolen its playlists for its iPod, iPad, and iPhones in a case of patent infringement. Because it was victorious in that lawsuit, Personal Audio received an eight million dollar settlement from the megacompany.20

Here are the typical, basic steps of a civil lawsuit: investigation, pleadings, discovery, pre-trial, trial, settlement, appeal, and enforcement of judgment.

Investigation All civil litigation goes through this initial investigation phase. The attorneys for the parties will typically be responsible for the investigation, and they may work with a private investigator as well. During this stage of the case, the party who has allegedly suffered some kind of harm will determine whether a lawsuit is warranted. If so, the lawyers will look for supporting evidence that can help their clients win or successfully defend their cases. This can include things such as evidence from an accident scene, medical records, and interviewing witnesses informally.

Pleadings Pleadings are the documents that are usually filed in order to initiate a lawsuit. Every person involved in a civil lawsuit files a pleading that details their side of the case. In Texas, the first and, typically, the most important of the pleadings is called the Original Petition. Petitions must be filed within two to four years of the act that serves as the basis of the lawsuit, depending on the type of lawsuit that is being brought by the plaintiff.

A petition will discuss the essential facts of the case, the legal issues, and a review of all alleged damages suffered. A copy of the plaintiff’s lawsuit must be delivered to the defendant before the defendant has any obligation to respond. Once served, however, the defendant is officially put on notice that a lawsuit has been filed and has thirty days to file what is typically called an Original Answer. When that happens, both parties have made an official appearance in the case, and the lawsuit proceeds as usual. However, if the defendant fails to respond to the petition within thirty days, the court may issue a default judgment in favor of the plaintiff. At that point, the plaintiff is no longer required to prove the defendant’s responsibility (which is, by the defendant’s inaction, admitted). The only unresolved matter is the damages the plaintiff can obtain.

Discovery The discovery stage of civil litigation involves fact gathering. Both sides involved in the case are able to formally exchange information about the upcoming trial during discovery. The discovery phase of a case helps prevent surprises during the trial and allows both sides to prepare equally. However, discovery is not without limits. Certain types of information are

generally protected from discovery, including information which is privileged (such as attorney- client communications, trade secrets, and conversations between spouses) and the work product of the opposing party and his attorney. Other types of information may be protected, depending on the type of case and the status of the party (juvenile criminal records, certain medical and psychiatric records, for example).

The parties, through their attorneys, may obtain evidence from the opposing party and others by means of discovery devices, including requests for answers to interrogatories, requests for production of documents and things, requests for admissions, and depositions.

- Interrogatories ask open-ended questions for the other party to answer. For example, one may ask the other party to identify all evidence upon which they intend to rely in support of their claims or defenses.

- Requests for production allow one party to ask the other to provide documents or other tangible evidence, including electronically stored information. This is the process used to actually obtain most of the physical evidence that the parties will rely on when they move toward trial.

- Requests for admission ask another party to admit or deny certain carefully worded questions. For example, one party may ask the other to admit certain specific facts related to an incident that would tend to prove that party's liability (fault). Requests for admissions allow a party to delve deeper into issues beyond those required to state a cause of action, such that certain reasonable inferences can be drawn.

- Deposition is the process of taking live testimony from witnesses and parties before trial. The witness or party is required to appear and testify under oath before a court reporter who records the entire proceeding. These proceedings are usually done in an attorney's office with representatives of both or all of the parties in attendance. While the testimony and questioning are governed by the usual rules of evidence, with no judge present to rule on any objections, they are usually just recorded by the court reporter and dealt with later if the testimony is introduced at trial. The court reporter transcribes depositions into booklets, the substance of which can be used at trial as if the deponent (the person offering the deposition testimony) was in trial if, in fact, he or she is absent.

Interrogatories, requests for production, and requests for admission and depositions are integral parts of the pre-trail discovery process.

Pre-Trial During this pre-trial stage of the case, the judge will determine whether contested pieces of evidence are admissible or inadmissible and whether witnesses will be considered as expert witnesses (witnesses with unique educations, expertise, experience, or other specialized skill sets whose opinion may help a jury make sense of the factual evidence of a case) or lay witnesses (witnesses who do not need to be qualified in any area to testify since their testimony about matters with which they have personal knowledge).

At this stage of the case, the attorneys for both sides enter into conferences and negotiations. In a large number of cases, the parties can reach a settlement during this stage (usually through a process called mediation). The plaintiff's attorney will make an initial monetary demand during this stage, and the defendant's attorney has a limited amount of time to counter that demand. The negotiations may go back and forth for some time, but the vast majority (about ninety-five percent) of cases are resolved before trial.

Trial A trial occurs when the case is not resolved during pre-trial. The trial is a formal process that allows both sides the opportunity to present their cases before a jury or judge (if neither party requests a jury trial). The first part of this stage includes the selection of the jury, assuming at least one of the parties to the lawsuit requests one. In most lower level courts, the jury will be composed of six people. In higher level courts, the jury will be composed of twelve people.

The process of selecting a jury is known as voir dire. During voir dire, a panel of people (called a jury pool) will be questioned by the attorneys for both sides about their background, beliefs, and biases. There is a misconception that the jury is selected from this larger panel. In fact, jurors are eliminated from the jury panel by what are called strikes.

Each side has an unlimited number of challenges for cause (strikes). Usually, a challenge for cause is made when a party believes a prospective juror has a bias against them or their attorney that may affect the outcome of the judgment of the case. This kind of strike is alleged by the attorneys and either accepted or rejected by the judge, who strikes or retains the prospective juror. Occasionally, the judge may attempt to “rehabilitate” the objectionable juror in order to keep that individual in the jury pool. Each side may also make a limited amount (usually six) of peremptory challenges. A peremptory challenge does not have to be explained. That is, each side can simply strike a certain number of prospective jurors from consideration. The amount of peremptory challenges varies according to the type of trial and the number of defendants.

During a civil trial, both sides can present evidence and witnesses. Attorneys for both sides can cross-examine witnesses during the trial. Because the plaintiff bears the burden of proof (meaning that he/she must prove the defendant’s responsibility by a preponderance of the evidence), the plaintiff’s attorney presents the case first. If the plaintiff’s attorney meets the necessary burden, only then does the defendant have the responsibility of presenting his/her case to the jury. If the plaintiff fails to meet the necessary burden of proof, the defendant may ask and receive a directed verdict (a verdict that is, as a matter of law, directed in favor of the defendant without the involvement of the jury). The outcome of a civil case is called a judgment. Settlement During any trial (or any other juncture of lawsuit), a settlement may be reached between the parties. As mentioned earlier about ninety-five percent of pending lawsuits end in a pre-trial settlement. If the settlement occurs during a trial, only the fact that the case has been resolved will be announced by a judge because, except in extraordinary circumstances, the terms of settlements are confidential. This settlement is considered a final outcome since all the parties have agreed to its terms.

Appeal If a party loses a lawsuit, that party’s attorney may file a Notice of Appeal (within thirty days of the Judgment) alleging that an error of law (committed by the trial judge) or an error of fact (committed by the jury) led to the rendition of an improper judgment. If no such error of law or fact occurred during the trial, there are no valid grounds for appealing the case. Typically, appeals move more quickly than the original case once they begin because the attorneys already have the benefit of having all the evidence and necessary information close at hand since it was recently needed for the original case. Once a party files for appeal, the party will not be required to comply with the court's judgment because an appeal acts like a freeze on the judgment. Enforcement of a Judgment Winning at trial does not necessarily resolve the legal issues if the primary goal of the plaintiff is to recover money from the defendant. If a judgment is entered on behalf of the plaintiff, that party is entitled to the amount of the judgment awarded by the jury. However, the prevailing party may encounter problems when trying to recover the money from the losing party. In that case, the plaintiff may be forced to commence collection proceedings against the losing party. This process begins with the filing of an Abstract of Judgment with the county or district clerk. In Texas, an Abstract of Judgment preserves a judgment for a period of ten years. As long as the defendant fails to pay the plaintiff the amount determined in the judgment, interest accrues on that amount.

Controversies: Tort Reform Civil claims include, but are not limited to, torts. A tort is an act or omission that gives rise to injury or harm to another and amounts to a civil wrong for which courts impose liability. In the context of torts, injury describes the invasion of any legal right.21 More specifically, torts are claims for any wrongful act that entitles an injured person to compensation. These claims include, among others, all personal injury cases that include assault, battery, trespass, false imprisonment, negligence, nuisance, defamation, invasion of privacy, and products liability.22

Since the 1970s, Texas has been embroiled in a continuing controversy relating to the issue of tort reform. Tort reform is a movement among some Texans who believe that laws should be changed in the civil justice system so that the volume of tort litigation and the damages resulting from those types of lawsuits are reduced. Generally, tort reform advocates want to make it more difficult for injured people to file a lawsuit, limit the amount of money or damages that injured people may receive as compensation for their injuries in a lawsuit, reduce damages that punish wrongdoers (punitive damages), and make it more difficult to obtain a jury trial.23

Tort reform was originally spearheaded by insurance companies and large corporations, who sought to attack the civil justice system and change rules of law, not through adjudication of cases over time, but through public perceptions and legislation limiting personal injury lawsuits.24 Those who advocated for tort reform sought to persuade the public that the civil justice system was unfair and corrupt and that its operations had adverse effects on the economy. They created advertisements and lobbying campaigns that supported the notion that the judicial process is biased towards plaintiffs, resulting in high liability insurance premiums. Conservative

politicians took on this cause, incorporating a change of the civil judicial system into their platforms.”25

In 2002, a conservative surge of voters ushered in Rick Perry to his first full term as governor, as well as a large class of freshman members in the House (led by Tom Craddick, then speaker of the House). Perry, conservatives in the Texas House, and a collection of lobbyists acting on behalf of a number of corporate interests, including insurance, oil and gas, pharmaceutical, medical, tobacco, liquor, chemical, nuclear waste, and construction companies, industry lobbyists powerfully led the way for tort reform.26

The public face of these lobbyists was the group Texans for Lawsuit Reform (TLR). TLR successfully advocated that justice administered by partisan, well-financed judges, resulted in inordinately excessive judgments which favored not only plaintiffs but also their attorneys. Perception against the manner in which civil cases were litigated had direct impact upon the state. Insurance companies placed surcharges on insurance issued in the state (resulting in higher premiums), and businesses hesitated to locate or expand in the state.27

In June 2003, Governor Rick Perry signed a bill into law that would significantly change the landscape for medical malpractice litigation in Texas. House Bill (HB) 4—commonly referred to as tort reform—was enacted to curtail frivolous lawsuits, limit runaway jury awards, and reduce malpractice liability insurance premiums.28

At that time, The Texas House and Senate were overwhelmingly dominated by Republicans. Predictably, tort reform in Texas has resulted in fewer lawsuits, smaller payouts to plaintiffs, and—to the benefit of physicians and other members of the health care community— significantly lower malpractice premiums.

Coupled with widespread public support, which favored—and still favors—lawsuit reform, legislators who advocated on behalf of TLR’s goals have consistently embraced and financed candidates for the elected members of all three branches of government.

Opponent of tort reform contend that restrictive legislation limits plaintiffs’ ability to seek full financial justice. They also claim that instituting restrictions and maximum caps on damages disregards each case’s unique circumstances and ultimately legitimately injured plaintiffs who may sense the need to settle cases rather than to try them to completion in the courts. Further, they suggest that increased insurance rates are a function of much more than the number of successful tort-related lawsuits.

Tort reforms have remained intact since HB 4 was signed by Governor Perry. The Republican Party’s dominance in the legislature has proved to be, thus far, an insurmountable hurdle to opponents of tort reform, as more than fifteen additional pieces of legislation that discouraged the filing of tort lawsuits (e.g., passing a law that required the loser in a lawsuit to pay the attorney's fees of the prevailing party) and restricting the ability of plaintiffs to pursue and win big-ticket personal injury claims have been passed.

Texas Criminal Processes

In the criminal justice system, the Texas court system must account for and address two conflicting goals: the need to protect the health, welfare and safety of the state’s people and the requirements to protect the rights and liberties of the accused. Unlike the civil court system, which strives for balance, the state’s criminal system incorporates an intentional bias in favor of the accused. In addition, the state must ensure that every person is treated equally in legal matters. This fair treatment through the normal judicial system, a general right to which each citizen is entitled, is known as due process. The Texas Code of Criminal Procedure lays down the rules that govern the criminal justice process. The issues addressed by the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure include, among others: courts and criminal court jurisdiction; the proper location for trials; arrest and bail; search warrants; trial procedures; courts costs, fees, fines, and restitution; appeals; as well as the prevention and reduction in the number of offenses.29

A criminal proceeding will follow the same stages of investigation, pleadings (called an arraignment in the criminal justice process), discovery, pre-trial hearings, trial, judgment, and appeals, but there are differences. The most significant difference is that the investigation is largely handled by the police, the defendant is arrested, and, if convicted, the punishment in a criminal proceeding is separate from the judgement of guilt or innocence and can include incarceration or even the death penalty. In Texas, as in most other states, the criminal process can take months or even years.

Arrest Unlike in a civil case, the local police or sheriff's department will normally investigate a case. The primary mechanisms used by law enforcement when investigating crimes are interviews of potential eyewitnesses, custodial interrogations of suspects, recorded observations, and collecting and preserving physical and forensic evidence at the crime scene. In some occasions, law enforcement officials are able to arrest a person accused of a crime at the scene of the alleged offense. But in other cases, law enforcement officials must rely on prosecutors to procure arrest warrants. In many cases, this type of arrest is based upon probable cause—the reasonable belief that a crime has been committed or is about to be committed. In such cases, law enforcement officials complete a sworn affidavit about the facts they have gathered in conjunction with their investigation. That affidavit serves as the basis for a prosecutor’s argument to a judge that an arrest warrant should be issued. An arrest warrant is a written order from a judge directed to a peace officer or some other person specially named to take an individual into custody. The arrest warrant is executed when the alleged perpetrator is arrested.

Prosecutorial Review If an accused it not yet arrested by law enforcement officials, once the investigation is substantially completed, those officials will present the case to the county attorney or district attorney, depending on the severity of the offense alleged. These conduct a prosecutorial review to determine whether there is enough evidence to charge the suspect with an offense, and if so, what type of offense. They also review the case and determine if there is enough evidence to proceed to court look for possible legal problems that may affect the case. These attorneys may also request additional investigation or information if they believe the potential case is questionable.

Complaint, Information, or Indictment A complaint is a document that officially charges a person with a crime. It must be sworn to by someone with knowledge of the crime. If there is sufficient evidence, and the law supports a criminal case, the suspect may be charged with a crime by a legal document called an information. An information is a formal charging document typically used for more minor crimes.30 The prosecutor may file an information and obtain an arrest warrant from a court for the accused if that individual has not already been arrested. An information is often the charging document used by prosecutors in misdemeanor cases.

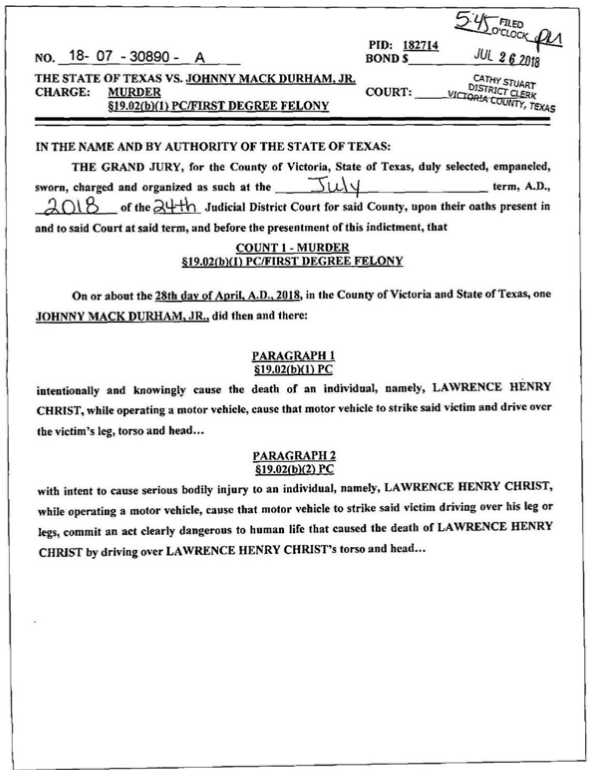

Grand juries are provided for in Article 1, Section 10 of the Texas Constitution and are required for felonies. A grand jury is not a typical jury as most people think. It does not serve for the entire length of a trial, nor does it determine the guilty or non-guilt of an individual. Rather, its sole purpose is to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to bring a formal charge against an accused. A grand jury is secretly convened by the county. An explanation of the law and the evidence that has been reviewed by the jurors is offered by a prosecutor, whose legal obligations are far less than they are in a traditional jury setting. The accused, but not his or her attorney, may be present at a grand jury proceeding, but that individual may not introduce evidence, examine witnesses, or do anything else but play the role of spectator. If the prosecutor convinces only nine jurors that an accused should be formally charged, the resulting document is an called an indictment, which is also called a “true bill” (Figure 8.6) If the prosecutor fails to present sufficient evidence to convince the grade jury to indict, this results in a “no bill.”31

Arraignment An arraignment is a post-arrest court proceeding at which a criminal defendant is formally advised of the charges against him or her and is asked to enter a plea to the charges. In Texas, the court may also decide at an arraignment whether the defendant has employed, or is financially capable of employing, an attorney. Once the lack of financial resources is alleged and proven, a court will declare the accused as indigent and will appoint an attorney to represent the defendant.

Discovery The same discovery (interrogatories requests for production, requests for admission, and depositions) may be conducted in a criminal case. Two additional types of evidence that may exist in a criminal, but not a civil, case are inculpatory evidence and exculpatory evidence. Any evidence favorable to the prosecution in a criminal case is inculpatory evidence, and any evidence that is favorable to the defendant in a criminal case is considered exculpatory evidence—evidence tending to excuse, justify, or absolve the alleged fault or guilt of a defendant. If, during the police investigation preceding trial, a witness was interviewed who claimed that another person, not the defendant, committed the crime, that witness interview is exculpatory evidence. Another example of exculpatory evidence would be DNA evidence on a knife in a murder case that links another individual to a crime.

Often the defendant will file pre-trial motions to "discover" the evidence held by the police and the attorney for the state. This evidence includes both inculpatory evidence and exculpatory evidence. The prosecutor is required to produce exculpatory evidence to the defendant’s attorney, but only if the defendant’s attorney specifically requests that information. Otherwise, the prosecutor has no legal obligation to supply it. This necessity has been mandated since the U.S. Supreme Court decided the case of Brady v. Maryland (1963).32

Pre-Trial The progress of most cases is determined by pre-trial orders, orders setting forth the procedural framework of a case to be tried, including a number of deadlines for specific tasks to be completed by the parties’ counsel. Thus, in addition to the state and local laws and regulations attorneys are required to follow pertaining to their conduct and the manner in which cases are conducted, they are also responsible for abiding by the provisions of a court’s pre-trial order. Among the court’s requirements is the parties’ appearance at a pre-trial conference.

During the pre-trial phase, a hearing between the judge and attorneys for the parties will occur shortly before the trial begins. It is during this hearing that the judge will rule on “evidentiary issues,” issues that relate to the admissibility or inadmissibility of evidence and the qualification of certain witnesses as expert witnesses. Often the defendant will file pre-trial motions to discover the evidence held by the police and the attorney for the state, and may file other motions to suppress evidence that the defendant claims should not be used at trial. The court often requires hearings on these motions that are often recording by the court reporter. These evidentiary hearings assist the court and the attorneys to more efficiently—with fewer legal interruptions—move the case through the trial.

The defendant and the prosecutor may enter into a plea agreement—any agreement in a criminal case between the prosecutor and defendant whereby the defendant agrees to plead guilty or nolo contendere (no contest) to a particular charge in return for some concession from the prosecutor)—at any time during the course of the trial. A plea agreement, however, must be approved by the judge. If no plea agreement occurs, the case proceeds to trial.

Trial Once a case goes to court, it may appear a number of times on the court's docket before it actually proceeds to trial. Once the court is prepared to hear the case, the jury selection process is similar to that in a civil case. For example, in a criminal voir dire, the judge and attorneys for both sides have the opportunity to ask potential jurors questions to determine if they are competent and suitable to serve in the case. However, there is one extraordinary distinction. Prosecutors may not use peremptory strikes to strike jurors from the jury pool based solely on the jurors’ race. This matter was considered by the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Batson v. Kentucky in 1985.33 The defendant’s attorney may challenge the sitting jury on this basis. A Batson challenge is an objection to the validity of the prosecutor’s use of peremptory challenges on the grounds that the prosecutor used those challenges to exclude potential jurors based on race, ethnicity, or sex.

The prosecution bears the burden of proving every element of each crime alleged in the case against the defendant. Until that case is fully proven by the introduction of evidence pertaining to every element of an alleged crime, the defendant bears no burden at all. Any misstep by the prosecutor during the trial could easily result in a verdict of not guilty. Also, the prosecutor must convince the jury of the defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, meaning that there must be no other reasonable explanation that can come from the evidence presented at trial but that the defendant committed the crime alleged. In addition, the jury verdict must be unanimous. This is an extremely difficulty burden for the prosecution to meet, but this requirement is justified when you consider that the punishment resulting after a conviction could be a lengthy incarceration or conceivably the death penalty.

The trial may be in front of a jury or a judge. A jury is required when the defendant’s punishment, if convicted, could include incarceration. The attorney for the state will call witnesses to testify about the crime. Once the attorney for the state introduces testimony from the state's witnesses, the attorney for the defendant may cross-examine those witnesses and even call rebuttal witnesses to dispute the testimony of the prosecution’s witnesses. The defendant is also entitled to call his or her own witnesses, who are also subject to cross-examination and rebuttal by the prosecution. However, the defendant is not required to introduce witness testimony, nor is the defendant required to give testimony because he or she has a constitutional right to remain silent. After all testimony has been heard, the jury must decide if the state proved its case against the defendant beyond a reasonable doubt. If so, the defendant is "guilty," a conviction occurs, and the jury proceeds to the punishment phase of the trial. If not, the defendant is declared "not guilty," and the he or she is free.34

Punishment Criminal trials in Texas are bifurcated trials, meaning they are divided into two separate parts, one for the judgment of guilt or innocence and the other for sentencing, if the defendant is found guilty. In the state, if the jury finds the defendant guilty, the second part of the bifurcated trial—the punishment phase—begins. The jury, not the judge, determines the punishment, and juries are somewhat restricted during this phase since the punishment ranges for both misdemeanor and felony criminal cases in Texas are set forth in Title 3, Chapter 12 of the Texas Penal Code.35

The punishment range is different for different crimes. Generally, misdemeanor crimes are punishable by time in the county jail and/or a fine, and felony crimes are punishable by time in the state prison or state jail and/or a fine. During this phase of the trial, both sides will once again offer evidence on what the proper punishment should be. The prosecution can introduce almost any information about the defendant, including information (e.g., prior criminal record, undesirable conduct, victim and other witness testimony) that tends to discredit the defendant to an even greater extent with the intent of convincing the jury to impose a much harsher sentence than might otherwise be justified. The defendant’s attorney, of course, will introduce evidence that might convince the jury to soften the punishment they ultimately give the defendant. Although jail time is often assumed, there are occasions when a defendant is eligible to be released on probation and continue to live in the community while being monitored for compliance with rules set by the court and thus avoid jail or prison time altogether.

Appeals Every convicted defendant has the right to appeal his or her case to an appellate court. Generally, the defendant appeals on the grounds that some error occurred at the trial that requires a reversal of the conviction. Regardless of the reason, an appeal must be filed within 30 days of the verdict (if the case is tried before a judge and jury) or judgment (if the case is an appeal from a lower appellate court). It is not uncommon for these appeals to take months if not years. During the time when the appeal is pending, the defendant is entitled to a bond if the sentence is fifteen years or less. If the case is reversed, the court of appeals may order a new trial. Oftentimes, because of the constitutional prohibition against double jeopardy and the hesitancy of some prosecutors to retry cases, the defendant “walks,” never again to be tried for the same crime in the same court.

Controversies: Bail Reform Recent public attention has been directed toward the issue of bail, the existence and amount of which is often resolved at the arraignment. “Bail is a legal mechanism to ensure that people charged with crimes show up to their court hearings.”36 The most common type is money bail, where judicial officers set a bond amount, based on the alleged crime, that an arrestee must pay in order to be released from jail before trial. Defendants can pay the court the full amount, which is refundable, if they show up to all their court hearings. Or they can pay a nonrefundable percentage of it—usually about ten percent—to a bail bonds company that fronts the total cost of getting them released before their trial.37 In some Texas counties, that range is prescribed by a preestablished schedule which gives a judge little or no discretion. In establishing the bail amount, the judge may also take into consideration the seriousness of the offense, the defendant's ability to make the bond, the safety of the victim, and the safety of the witnesses.

Bail can be tremendously expensive, even when obtained through a bondsman, especially for those who lack substantial or any income. Federal courts have consistently held that the Eighth Amendment, to the U.S, Constitution— “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted”38—prohibits the assessment of a bond set so high that it punishes defendants by unnecessarily keeping them in jail before trial. Many defendants ask courts to either lower the bail or release them under a personal recognizance (PR) bond, a written promise signed by the defendant promising that they will show up for future court appearances and not engage in illegal activity while during their release.

Local governments, including Harris County, have intervened in the assessment of bail at the local level. For years, some county officials criticized the fact that counties have relied too heavily on the monies derived from this system and that it unconstitutionally deprives the poor— who lack the cash necessarily to procure their release—of the right to be released from jail and to assist their counsel in their defense. In 2016, a lawsuit was filed against Harris County, alleging that several individuals charged with low-level offenses remained jailed because they could not afford to pay for their release. The following year, a federal judge declared this practice unconstitutional, thus prompting the county commissioners court to address the court’s findings that the county’s pre-trial system discriminated against poor misdemeanor defendants.39 Part of the settlement between the county and the plaintiffs included a new policy of “automatic, no- cash pretrial release for about eighty-five percent of low-level defendants. It also added additional legal and social services for poor arrestees and help for getting them to their court dates.”40

The issue has become even more heated due to the COVID pandemic, where those in jail are at higher risk. Many argued during COVID for early release and especially for releasing those who are being held for trial and haven’t been convicted of a crime. Governor Abbott blocked the jail release, however, due to long-held concerns that inspired the Damon Allen Act. State trooper Damon Allen was killed by a man who had recently been released on bail. Abbott wants to overhaul the bail system in 2021. The controversy over jailing the poor remains.

20. “Tort,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/tort.

21. “Tort,” https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/tort.

22. “Tort Reform,” Justia, https://www.justia.com/injury/neglig...y/tort-reform/.

23. “Tort Reform,” https://www.justia.com/injury/neglig...y/tort-reform/.

24. “Tort Reform,” https://www.justia.com/injury/neglig...y/tort-reform/.

25. The Texas Watch Foundation, “Ten Years Later: How House Bill 4 has Harmed Texans,” https://www.textrial.com/ten-years-l...harmed-texans/.

26. “Our Mission,” TLR, https://www.tortreform.com/our-mission.

27. Catherine Greaves, “The Effects of Tort Reform in Texas,” CRST Cataract & Refractive Surgery Today, May 2014, https://crstoday.com/articles/2014-m...form-in-texas/.

28. Tex. Code of Crim. Procedures, https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/?...5.00.000021.00.

29. “Information,”American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, fifth edition (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), https://www.thefreedictionary.com/information.

30. Findlaw., “How Does a Grand Jury Work?” Thomson Reuters, Nov. 9, 2020, https://www.findlaw.com/criminal/cri...jury-work.html.

31. Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963).

32. Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1985).

33. Tex. Code of Crim. Proc., Ch. 36 (1965), https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/D.../htm/CR.36.htm.

34. Greg Tsioros, “When Are You Eligible for Parole in Texas?” Oct. 4, 2017, https://txparolelaw.com/eligible-for...from%20custody.

35. Jolie McCullough, “Harris County Agreed to Reform Bail Practices that Keep Poor People in Jail. Will It Influence Other Texas Counties?” Texas Tribune, July 31, 2019, https://www.texastribune.org/2019/07...-dallas-texas/.

36. McCullough, “Bail Practices,” https://www.texastribune.org/2019/07...-dallas-texas/.

37. U.S. Const. amend VIII.

38. McCullough, “Bail Practices,” https://www.texastribune.org/2019/07...-dallas-texas/.

39. McCullough, “Bail Practices,” https://www.texastribune.org/2019/07...-dallas-texas/.

40. “Judicial Selection in the States,” Ballotpedia, 2020, https://ballotpedia.org/Judicial_sel..._in_the_states.