12.6: The Texas Correctional System

- Page ID

- 129210

Before a central state penitentiary was established in Texas, local jails housed convicted felons. The Congress of the Republic of Texas defeated bills for a penal institution in both 1840 and 1842; in May 1846 the First Legislature of the new state passed a penitentiary act, but the Mexican-American War prevented implementation of the law. Before a central state penitentiary was established in Texas, local jails housed convicted felons. The Congress of the Republic of Texas defeated bills for a penal institution in both 1840 and 1842; in May 1846 the First Legislature of the new state passed a penitentiary act, but the Mexican-American

War prevented implementation of the law. On March 13, 1848, the legislature passed the act that began the Texas penitentiary. The law authorized gubernatorial appointment of three commissioners to locate a site and choose a superintendent and three directors to manage the treatment of convicts and administration of the penitentiaries.

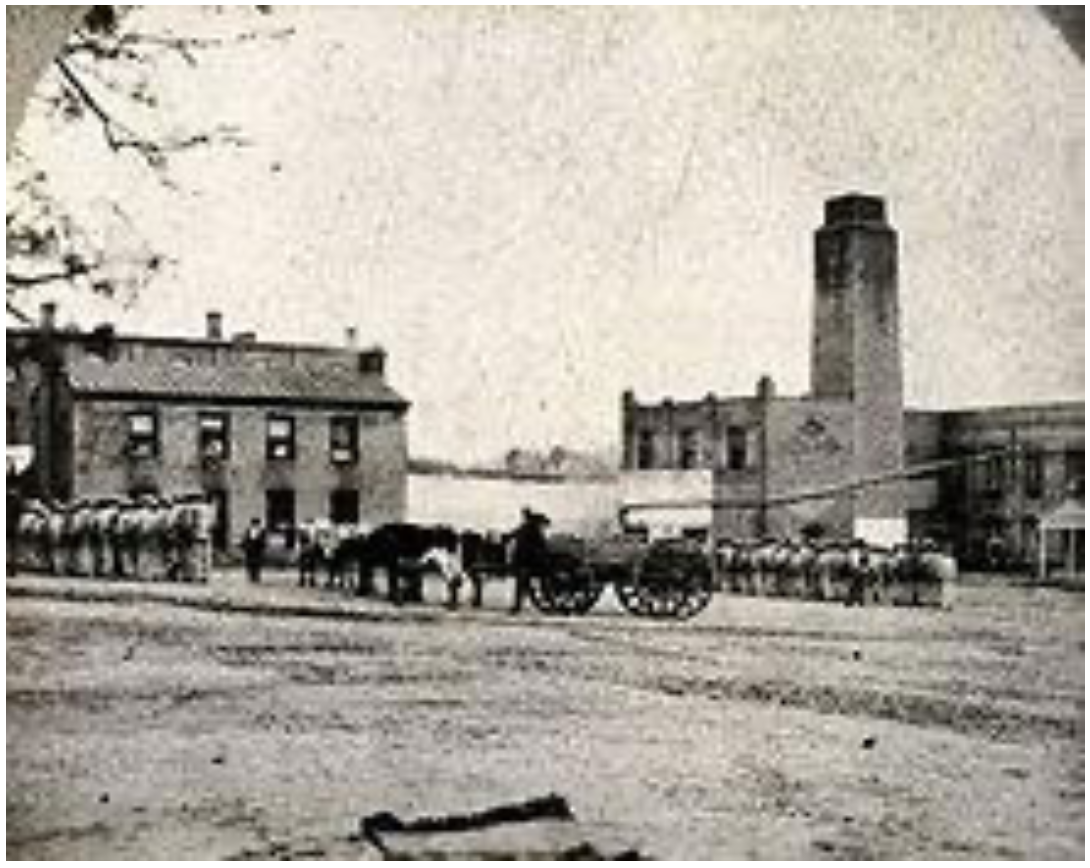

After the commissioners selected Huntsville, in Walker County, for the site, construction began on August 5, 1848, and continued for several years (Figure 12.3). Abner H. Cook supervised the construction and was the first superintendent of the prison. On October 1, 1849, the first prisoner, a convicted horse thief from Fayette County, entered the partially completed Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville. The law authorized gubernatorial appointment of three commissioners to locate a site and choose a superintendent and three directors to manage the institution. Today, the state operates the largest prison system in the United States.57

Texas’s criminal justice system has three components. Those three stages consist of law enforcement and criminal prosecution, trial and appeals, and corrections.58 Each of these stages is comprised of multiple levels, organizations and many thousands of personnel. The nine member Texas Board of Criminal Justice is appointed by the governor to oversee the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ, which includes the massive task of overseeing corrections, including 8confinement, supervision, rehabilitation, and reintegration of the state’s convicted felons. The board is a separate agency from—but works closely with—the TDCJ. The board members, who are appointed for staggered, six-year terms, are responsible for hiring the executive director of the department and setting rules and policies which guide the agency.59 The department encompasses these major divisions:

- Correctional Institutions Division

- Parole Division

- Community Justice Assistance Division

Correctional Institutions Division

The Correctional Institutions Division operates prisons, which are facilities for nearly 135,000 people convicted of capital offenses and people convicted of first-, second-, and third-degree felony offenses, and state jails, facilities for people convicted of state jail felony offenses. Texas leads the nation in imprisoning its citizens with the largest incarcerated population under the jurisdiction of its prison system. In addition, Texas has been the top state for state prison growth, with a rate of nearly twelve percent compared to the nation’s average of six percent. Nearly one in five new prisoners added to the nation’s prisons was in Texas, and one fourth of the nation’s parole and probationers are in Texas.60

State Prisons The TDJC is headquartered in Huntsville, where it currently operates over 100 state prisons.61 The Texas Prison System purchased its first prison farm in 1885. Historically, the Huntsville Unit served as the administrative headquarters of the Texas Prison System; the superintendent and the other executive officers worked in the prison, and all of the central offices of the system's departments and all of the permanent records were located in the prison.

In the 1960s, the Texas Prison System began referring to the prisons as "units". Texas began building prisons outside its traditional locations in the 1980s.62 The average annual growth of Texas' prison population during the 1990s was 11.8 percent. This rate of growth was not only the highest growth in the nation, but was almost twice the average annual growth of the other states during that same period.63 Predictably, this exponential growth in the number of inmates always requires the construction of new prisons.

The Death Penalty Any discussion about the state’s correctional institutions must include more than a casual reference to the death penalty. Texas was the first state to use private prisons.64 During the 1980s, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) experienced an overcrowding crisis. Admissions to Texas prisons increased by 113 percent from 1980 to 1986, and outpaced system capacity increases by fifty-two percent.65 In 1987, Texas legislators overwhelmingly passed Senate Bill 251 to allow contracts with private prison vendors to manage and construct private prison facilities.66 Proponents of private prisons argued that they would increase the quality of care by improving rehabilitation and reducing recidivism rates. Opponents to privatizing incarceration in Texas argue that profit incentives may put financial gain above the public interest of safety and rehabilitation.67

Before 1923, counties carried out their own executions, by means of hanging. Now, The Huntsville Unit is the location of the State of Texas execution chamber (Figure 12.4). In 1923, the state of Texas ordered all executions to be carried out by the state, in Huntsville, by means of the electric chair. Texas electrocuted 361 inmates from 1924 to 1964. In 1964, judicial challenges to capital punishment resulted in a temporary prohibition of executions in the United States. In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that every state death penalty law in the U.S. was unconstitutional because the death penalty was being unfairly and arbitrarily assigned.68 Thereafter, the governor of the state commuted the death sentences of the fifty-two men on death row to life imprisonment. However, four years later, the Supreme Court held that the imposition of the death sentence did not violate the Eighth Amendment prohibition of "cruel and unusual" punishment.69

In 1977, Texas adopted lethal injection as its means of execution, adopting a three-drug protocol. The injection now consists of a single dose of pentobarbital, a fast-acting barbiturate also used in animal euthanasia. The first lethal injection was administered in 1982. Although executions that year, they were rare. One execution was carried out in 1982, and none in 1983. For the next eight years, executions were carried out at the average rate of five per year. Thus, in the first ten years of capital punishment in Texas, there were forty-three executions. In 1992, the number of executions jumped dramatically. Over the next four years, sixty-two prisoners were executed, an average of fifteen per year.70

In 1995, the Texas legislature passed a law requiring certain death-row appeals to be filed concurrently. The intent of this law was to reduce the amount of time prisoners spent on death row (which is currently just short of eleven years) waiting for their legal appeals to be pursued. The short-term effect of this new law was that executions virtually stopped while it was being appealed. From March 1996 to January 1997, there was only one execution in the state. However, after the law withstood legal challenge, executions resumed at double their old pace. Over the next three years, there were ninety-two executions.71

In 2000, several factors caused the death penalty to come under scrutiny. Among those were (1) the continuing arguments that the existence of the death penalty and the methods by which it was administered is cruel and unusual; (2) legitimate studies that consistently exposed racial disparities at nearly every stage of the capital punishment process,

from policing and charging practices, to jury selection, to jury verdicts, to which cases result in executions; 3) a national consensus against the executive of the mentally impaired; and 4) the Supreme Court’s ruling in 2005 that prohibited the imposition of the death penalty upon those who were under age of eighteen when they committed capital crimes. Predictably, Texas came under especially strong national scrutiny in 2000 because, at the time, it led the nation in executions—more than all other thirty-seven death-penalty states combined.72

Between 2000 and 2005, the average number of executions per year in Texas declined. Since then, the number of executions per year resumed at a more moderate pace. In 2005, Texas changed the law so that capital murderers sentenced by juries to either the death penalty or life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. Since then, Texas juries have demonstrated a tendency to sentence those convicted to life imprisonment.73 There are over 200 people on death in Texas.

State Jails The Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) oversees seventeen state jails, fourteen directly and three through private contractors, in sixteen counties throughout the state. The state jails’ annual employee payroll for fiscal year 2019 was over $225 million.74 Unlike county and municipal jails, state jail facilities are not intended for those awaiting trial or serving brief sentences for misdemeanors. State jail inmates are convicted felons—usually for lower level assault and drug, family, and property offenses—although they serve shorter sentences than most of those incarcerated in conventional prison units. Texas created the state jail felony classification in 1993 as part of a reformation of sentencing laws. It was intended to address overcrowding in prisons caused by extensive prosecution of drug-related crimes. Over five years later, over fifty percent of state jail felons were convicted of possession or delivery of a controlled substance. State jail felonies include: burglary of a building; coercing a minor to join a gang by threatening violence; credit card abuse; criminally negligent homicide; criminal nonsupport; cruelty to animals; driving while intoxicated with a child passenger; evading arrest in a vehicle; false alarm or report; forgery of a check; fraudulent use/possession of identification; white collar fraud getting a hard money loan; improper photography or visual recording; interference of child custody; possession of less than one gram of a controlled substance; theft of something valued between $1,500 and $20,000; and unauthorized use of a vehicle.75

The punishment range for a State Jail Felony is 180 days to two years in the State Jail Division of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) and up to a $10,000 fine. Since 2011, moreover, state jail inmates have been able to reduce their sentences by up to twenty percent by completing work or treatment programs offered by state jails. A judge must approve the sentencing reduction after this “diligent participation” is completed.76 More than half of state jail felons participate in some programming while incarcerated, and most recently, about half of those discharged used credits to reduce their stays by an average of forty days.77

In 1995, the Legislature allowed defendants eligible for state jail to opt to serve their sentences in local jails or to be prosecuted for Class A misdemeanors, which involve lesser penalties without state jail time and, usually, no probation requirement.78

Parole Division

The TDCJ Parole Division supervises released offenders who are on parole, inmates in the state’s pre-parole transfer program, and inmates in work programs. The division also investigates proposed parole plans from inmates, tracks parole eligible cases, and submits cases to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles. The division does not make decisions on whether inmates should be released or whether paroles should be revoked. The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles decides which eligible offenders to release on parole or discretionary mandatory supervision, and under what conditions. The Board uses research-based Parole Guidelines to assess each offender's likelihood for a successful parole against the risk to society. It also decides whether to revoke parole if conditions are not met, using a graduated sanctions approach. Depending on the seriousness of the violation, the Board may continue parole, impose additional conditions, place the offender in an Intermediate Sanction Facility, or use other alternatives to revoking parole and sending the offender back to prison. Additionally, the Board recommends clemency matters, including pardons, to the governor.79

The parole division contracts with several agencies which operate halfway houses (also called residential reentry centers or sober living facilities) in thirty-seven cities in the state. According to state law, former prisoners must be paroled to their counties of conviction, usually their home counties, if those counties have acceptable halfway-housing facilities available. Most counties do not have such facilities available. Far fewer than the existing number of the existing facilities accept sex offenders, whose post-release conduct is governed by the Texas Sex Offender Registration Program. The program requires adult and juvenile sex offenders to register with the local law enforcement authority of the city they reside in or, if the sex offender does not reside in a city, with the local law enforcement authority of the county they reside in.80

Because of aspects of state law and because of a shortage of halfway houses, almost two-thirds of the sex offenders housed at the primary facility in Harris County are originally from another county. All people released receive a set of non-prison clothing and a bus voucher. State jail offenders receive a voucher to their counties of conviction. Prison offenders receive fifty dollars upon their release and another fifty dollars after reporting to their parole officers. Released state jail offenders do not receive money.

The Community Justice Assistance Division supervises adults who are on probation. In 1989, the Seventy-First Texas Legislature began using the term community supervision in place of the term adult probation. It is responsible for the distribution of formula and grant funds; the development of standards, including best-practice treatment standards; approval of Community Justice Plans and budgets; conducting program and fiscal audits; and providing training and certification of community supervision officers.81

57. Paul M. Lucko, “Prison System,” Texas State Historical Association Handbook of Texas (2020), https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/.../prison-system.

58. “Understanding the Lone Star State’s Criminal Justice System,” Texas State Records (2020), https://texas.staterecords.org/under...he%20community.

59. Texas Department of Criminal Justice, “Texas Board of Criminal Justice” (2020), https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/tbcj/index.html.

60. “Lone Star State’s Criminal Justice System,” https://texas.staterecords.org/under...he%20community.

61. Robert Perkinson, Texas Tough: The Rise of America’s Prison Empire (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2010), 56-57.

62. Perkinson, Texas Tough, 56-57.

63. Dana Kaplan, Vincent Schiraldi, and Jason Ziedenberg, “Texas Tough: An Analysis of Incarceration and Crime Trends in the Lone Star State,” Justice Policy Institute, Oct. 1, 2000.

64. Philip A. Ethridge and James W. Marquart, “Private Prisons in Texas: The New Penology for Profit,” Justice Quarterly 10, no. 1 (1993), 29-48, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/...18829300091691.

65. Lucko, “Prison System,” https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/.../prison-system.

66. Lucko, “Prison System,” https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/.../prison-system.

67. Kara Gotsch and Vinay Basti, “Capitalizing on Mass Incarceration: U.S. Growth in Private Prisons,” The Sentencing Project (2018); Robert Draper, “The Great Texas Prison Mess,” Texas Monthly, May 1996, https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/the-great- texas-prison-mess/.

68. Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972).

69. Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976).

70. David Carson, “History of the Death Penalty in Texas,” Texas Execution Information Center (2020), http://www.txexecutions.org/history.asp.

71. Carson, “History,” http://www.txexecutions.org/history.asp.

72. Carson, “History,” http://www.txexecutions.org/history.asp.

73. Carson, “History,” http://www.txexecutions.org/history.asp.

74. Patrick Graves, Fiscal Notes - The State Jail System, Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts (2019).

75. Trey Porter Law, “What is the Punishment Range for a State Jail Felony?” https://lawfirmsanantonio.com/faqs/w...am-i-eligible/ (2020).

76. Texas Department of Criminal Justice, “State Jail Diligent Participation Credit: Overview,” https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/divisions...ss_HB2649.html, accessed 2021.

77. Patrick Graves, “Fiscal Notes - System Changes,” Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts (2019).

78. Patrick Graves, “Texas State Jails - Time for a Reboot?” Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts (2019).

79. Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles, “Clemency – What is Clemency?” (2020).

80. Texas Department of Public Safety, “Texas Sex Offender Registration Program” (2020).

81. “Texas Prisons,” Texas Almanac (Austin: Texas State Historical Society, 2018), https://texasalmanac.com/topics/gove.../texas-prisons.