1: Sleep Wellness

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 155929

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

The previous chapter likely convinced you of the importance of sleep, but how do you get that sleep? Identifying and establishing the behavioral changes necessary to improve sleep can be elusive, so I will guide you through a simple methodical approach for success. Rest assured, most people start sleeping better after making a few small adjustments to their routines or environment. This chapter will help you create habits for boosting your sleep.

To begin, identify your current level of sleep wellness with the SATED questionnaire, published by Daniel Buysse in 2014.1 (In the article, scroll down to Figure S1 for the questionnaire.) Part of the motivation in the development of SATED was to help researchers and clinicians move away from a sleep disorder–centric model of thinking and provide a way to assess and promote sleep health. This is because if we view wellness as an absence of disease, we are missing opportunities to increase health in our communities. By defining, and thus being able to evaluate, a person’s sleep health, we have a better opportunity to prevent disease, maximize wellness, and have an impact on entire communities. Concerns can be addressed, and educational interventions taken, to prevent the tragic effects of sleep debt. If, in addition to the traditional programs focused on disease treatment, political and health-care policies support health practitioners in assessing the well-being of individuals and communities to determine educational targets, we could take a significant leap toward increasing vitality and preventing disease.

In his article, Buysse stresses the difficulty of conducting meaningful research and making health policy changes without a clear understanding of sleep health, pointing to the lack of a clear definition of this term in the scientific literature and the field of sleep medicine. The SATED questionnaire is part of his attempt to provide a better understanding of what constitutes healthy sleep. He considers sleep health to have five dimensions:

- • Satisfaction with sleep

- • Alertness during waking hours

- • Timing of sleep

- • Efficiency of sleep

- • Duration of sleep

Determining Sleep Need

Before diving into detail about how to get good sleep, let’s agree on how much is enough. For most adults, it is around eight hours, and for many adults, a little more than eight. Even if you get that much, you may wonder how to verify if it is of good quality. That is easier to ascertain than you might imagine.

Here are questions to ask to determine if you are getting adequate sleep:

- 1. After being up for two hours in the morning, if you were to go back to bed, would you be able to fall asleep?

- 2. If you did not set your alarm, would you wake up automatically at the desired time, feeling refreshed?

- 3. Without caffeine or nicotine during the day, would you easily stay awake and alert?

- 4. When you go to bed at night, do you fall asleep “when your head hits the pillow”?

- 5. Do you doze off during a boring meeting, conversation, or TV show? (Figure 1.1).

Answers to these simple questions reveal if you’re getting enough good-quality sleep. If it is adequate, your answer to questions 2 and 3 would be yes but no to questions 1, 4, and 5. Question 4 is the only one that may not be obvious: some of you likely believe it is a healthy sign to fall asleep immediately upon getting in bed, but that in fact is a sign of an extreme lack of quality sleep. It should take about fifteen minutes to fall asleep if a person is getting enough good sleep each night. Similarly, regarding question 5, a person might assume they are getting ample sleep and that it is normal to doze off if they had an exhausting day and are watching a TV show in the early evening. However, these situations are actually unmasking sleep debt and are a signal that more sleep is needed.

What about sleeping too much? This concern can often be traced to a misinterpretation of research showing a correlation between nine or more hours of sleep a night and a shorter life-span. However, there is no evidence that more good-quality sleep is the cause. Rather, having a disorder such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) can cause a person to stay in bed nine or more hours a night (see chapter 6). In this case, they will report they are “sleeping” nine or more hours, but unbeknownst to them, they are not actually getting quality sleep during those nine hours, and that is why they end up staying in bed so long. After the eighth hour in bed, their body is still trying to get sleep because they may have been awakened, without knowing it, hundreds of times during the night due to breathing issues. So untreated OSA is what increases the risk of an earlier death, not excessive sleep. Someone without OSA who spends nine hours each night going through healthy sleep cycles and feels refreshed throughout the day would not have an increased risk of an earlier death. Please use this content to deliberate with a classmate about correlation versus causation.

One factor that must be included in discussions of the ideal amount of sleep is sleep opportunity. Going to bed at 11:00 p.m. and arising at 7:00 a.m. does not mean a person has slept eight hours. This means the person was providing themselves a sleep opportunity of eight hours (the time they spent in bed) with the time of actual sleep still to be determined. This is often an area of confusion in interpreting population studies of sleep. In questionnaires, people likely report that they sleep eight hours if they are in bed from 11:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m. However, if you have those same individuals wear an actigraphy device or polysomnography equipment, the results may show that during those eight hours, they sleep less than four hours or, under the best of circumstances, seven and a half hours (see chapter 2 for a discussion of actigraphy and polysomnography). You may be wondering why, under the best of circumstances, eight hours of sleep would not be obtained after eight hours in bed. This is because it is normal to take fifteen minutes to fall asleep (as mentioned at the start of this chapter) and to have a few tiny awakenings during the night (most of which we are usually unaware). If we recommend a person get eight hours of sleep, we are referring to actual sleep, which requires being in bed for eight hours plus the time it takes to fall asleep and any additional time for awakenings during the night. This means most people need to give themselves a little over eight hours in bed each night.

One fascinating study that received considerable press—press that misrepresented the scientists’ conclusions—was regarding hunter-gatherer tribes and their sleeping less than seven hours a night. Understanding this study will help you comprehend the difference between sleep efficiency and sleep opportunity as well as encourage you to think critically when hearing news stories. Consider, for example, how a headline in popular media that tells people “You do not really need 8 hours of sleep” will sell magazines. Even though that was likely not the intention of the scientists who conducted the study, this distortion of the results made for profitable press. But what actually happened?

The researchers studied people from three tribes: the Hadza (Tanzania), Tsimané (Bolivia), and San (Kalahari; Figure 1.2). The idea was that since these are preindustrial tribes, the way they sleep is how we city dwellers should too. The members of the tribes wore actigraphy devices that showed an average of 6.75 hours of sleep per night for the duration of the study. A layperson’s interpretation of this could be that the tribal member was in bed for 6.75 hours; consequently, that layperson may believe they achieve optimal sleep health if they go to bed at 1:15 a.m. and get up at 8:00 a.m. However, for a sleep efficiency of 85 percent (the low end of the healthy range), a person would have to be in bed 7.9 hours to get 6.75 hours of sleep (see chapter 2 for a discussion of sleep efficiency).

But wait—how long does it take the person to fall asleep? Under ideal circumstances, a person falls asleep in 15 minutes (0.25 hour), so add 0.25 hours to the 7.9 hours to get 8.15 hours (8 hours and 9 minutes). This means that if a person has both healthy sleep efficiency and sleep latency (time to get to sleep), they need to be in bed 8.15 hours to get 6.75 hours of sleep. It is doubtful that most people interpreted the popular-press headlines (boasting we need less than 7 hours of sleep) of this research as guidance to be in bed for over 8 hours; rather, many people probably ended up getting less than 6 hours a night, thinking they were on track because they allowed themselves 6.75 hours of time in bed as their new healthy goal. The actual study supports this as well: the tribespeople were giving themselves between 7 and 8.5 hours of sleep opportunity a night.2

As a science student, the lesson for you in this is to think critically when reading news stories, ask yourself if the reporter has an agenda, and most importantly, look for the source of the data and find the original article. See if that article is in a peer-reviewed scientific journal, and read the article itself critically as well.

In his book Why We Sleep, Matthew Walker, PhD, adds further fuel to the argument that these tabloid headlines are harmful and misguided. He points out that the life expectancy for people in these tribes is fifty-eight years, a number very close to the projected sixty-year life-span of an adult in an industrialized country who gets 6.75 hours of sleep a night. He also refers to animal studies indicating that the cause of death in sleep-deprived animals is the same lethal intestinal infection that is the cause of death for many of the tribespeople of the study. He reasons that the tribespeople may be sleeping 6.75 hours, but they might live longer if they were to sleep more. He then postulates that the reason they sleep less is due to a lack of sufficient calories; they border on starvation for a significant part of each year. There are physiological cascades that shorten sleep if the body needs to spend more time acquiring food. This is clearly not the goal for a person looking for the ideal amount of sleep to get each night for the sake of health optimization and longevity.

Napping

Napping makes us stronger, faster, smarter, and happier, and it helps us sleep better at night. From the prophet Muhammad, who recommended a midday nap (qailulah), to the Mediterranean concept of a siesta, napping has spanned cultures and the ages (Figure 1.3). The word siesta derives from Latin: hora sexta, meaning “sixth hour.” Here is why that makes sense: the day begins at dawn, around six in the morning; consequently the sixth hour would be around noon—siesta time! Only recently have modern North Americans, on a larger scale, embraced the practice of napping, thanks to extensive research showing the mental and physical health benefits of a brief amount of sleep shortly after midday. This is the time we have a genetically programmed dip in alertness—the signal to nap—that is a function of our human circadian rhythm, regardless of ancestry.

If we take the sleep wellness advice, adjust our routines, and start getting eight hours of sleep a night, it can feel disappointing to still feel drowsy in the afternoon. However, it is time to create a new habit of celebrating that afternoon slump as a healthy response in the body, even after sleeping well the night before. Drowsiness at this time is a valuable reminder to take a ten- to twenty-minute nap. Remember to set an alarm to train the body to limit the nap’s duration, and with practice, you will wake up just before the alarm sounds. The groggy feeling upon awakening from a nap might be a deterrent for even an ardent napper. This is sleep inertia, and with a more regular napping routine, it will be easily managed. Knowing you will have that sensation and that it will pass, usually within ten minutes, will make it easier to settle down for the nap. Some people who enjoy caffeine, and have tested to be sure it is not affecting their nighttime sleep, might want to have some right before their nap or immediately upon waking to help manage sleep inertia, but this isn’t always necessary. The quality of clear and relaxed energy that takes you well into the evening, as opposed to the energy crash from not napping and using caffeine or nicotine in place of a nap, is usually enough to motivate someone to maintain a napping habit. Since the body has not been on a roller coaster of drowsiness during the day, thanks to the missed nap and possibly the use of stimulants, it approaches bedtime in a more even and restful state, and a better night’s sleep should follow.

Students hoping to optimize their study efforts would be wise to close the book and take a short nap (Figure 1.4). Naps increase memory performance, and scientists have documented particular types of brain activity that are associated with enhanced learning during naps, including sleep spindles (see chapter 2). When working on a homework set, the skill of restructuring—viewing a problem from various perspectives and creating a novel vision—is an ingredient for success that can be obtained via a brief afternoon snooze. Combine this with the amplification of creativity after napping and we see why students at colleges around the world are finding ways to get a nap on campus (see chapter 7).

When trying to avoid a cold or the flu, people are willing to spend a lot of money on immune support supplements and vitamins, but one of the strongest ways to provide powerful immune support is free (Figure 1.5). After a night of poor sleep, antiviral molecules such as interleukin-6 drop and reduce immune system power. However, a nap can bring those levels back to normal. Researchers have also found increased levels of norepinephrine, the “fight or flight” molecule, after reduced nighttime sleep. Sustained high levels of norepinephrine, associated with the stress response, have harmful effects on blood glucose balance and cardiovascular health. Napping brought the norepinephrine levels back within their normal range. Similarly, since one in three adults in the US have high blood pressure, it is welcome news that a daily nap can bring that down as effectively as medications and other lifestyle changes.

Athletes have been converting en masse to napping based on research showing the benefits it has for athletic performance as well as increased motor learning, even after a nap as short as ten minutes (Figure 1.6). Athletes, such as sprinter Usain Bolt, have shared stories of napping earlier in the day before a record-breaking performance. Adam Silver, National Basketball Association commissioner, cautions those who want to contact athletes during siesta time, “Everyone in the league office knows not to call players at 3 p.m. It’s the player nap.”

If you are still not convinced of the importance of napping, consider the distressing consequences when many healthy Greeks gave up napping. This occurred when business owners in many Greek communities began deciding to keep the businesses open rather than shut down for a siesta as they always had. Around that time, Harvard researchers examined over twenty thousand Greek adults with no cardiovascular disease. When they followed up after several years, the individuals who had given up napping had seen a 37 percent increase in their risk of dying from heart disease. For working men, it was an over 60 percent increase. A more hopeful way to view this is that the risk of dying was reduced by these significant amounts for those who continued napping.

Sleep Wellness Guidelines: Daytime, Before Bed, In Bed

Refer to the Sleep Wellness Guide below and take inventory, noting areas that you need to address. Prioritize each of those problem areas based on the significance of its impact on sleep, the feasibility of making change, and the value its implementation would have for the individual. This increases success by helping people see the flexibility of the approach and how they can control the process.

- • Significance: If a person is having caffeine late in the day and it is keeping them awake, the caffeine is having a significant impact on their sleep. Therefore, avoiding caffeine—or having it earlier—may solve the problem without the need to address less significant areas. Putting the effort toward changing behavior in less significant areas while continuing something significantly disruptive, such as caffeine intake, might not result in any improvement. In addition to being ineffective, it is frustrating because you feel like you are putting in effort and not getting results.

- • Feasibility: All items on the Sleep Wellness Guide are not feasible for everyone. If someone is a shift worker or caring for a family member, it may not be possible to get to bed at the same time every night. Determine a way to address this item that recognizes the reality of the situation. For example, could you go to bed and get up at the same time four days a week and maintain a different sleep schedule the other three days.

- • Value: Do you really enjoy that bowl of ice cream when watching a movie right before bed? Sleep wellness is not about giving up life’s pleasures. One sleepless client I worked with told me he had addressed all the items in his sleep wellness inventory but was still not getting quality sleep. We went over his daytime and evening routines, and I found out he truly treasured his ice cream, a generous serving of it, shortly before bed. I did not want him to deprive himself of this pleasure. He agreed to instead switch from a large to a small bowl to reduce the serving size. I asked him to choose an artistically pleasing little bowl, hoping to tap into an additional pathway to the reward center of his brain. We discussed the concern of heightened sugar levels right before bed and decided to offset this by, in addition to reducing the portion, rolling up a piece of sliced turkey and eating it while he scooped his ice cream into the bowl. This would help balance out the sugar-to-protein ratio of his late-night snack. Now, he still gets to sit and enjoy his bowl of ice cream, but thanks to those adjustments, his sleep is now satisfactory.

Sleep Wellness: Beyond the Guide

After reviewing each of the items in the Sleep Wellness Guide, synthesize the content with a deeper understanding of the science behind the practices.

Light

Chapter 3 provides elucidation about the role of light in regulating your sleep-wake cycle, while this section provides details about how to use the timing and quality of light exposure to improve sleep health. Sunlight or bright indoor light on the face in the morning is helpful to correct the circadian rhythm of someone who is not sleepy until late at night—a night owl—or has a difficult time waking up at the desired hour. Then, in the evening, establish a routine with reduced (or preferably, no) blue/white light exposure two hours before bedtime. This light so close to bedtime disrupts the circadian rhythm and interferes with sleep quality. In the evening, use solely amber- or orange-colored lights for illumination (Figure 1.7). For the phone, computer, and TV, utilize apps that filter blue light (the display will appear slightly orange). Alternatively, donning a pair of amber eyeglasses that block blue light will carry you into the bedtime hours, reassured that your melatonin secretion will not be disrupted by, for instance, preparing tomorrow’s lunch in a well-lit kitchen (Figure 1.8). Consider switching to an orange night-light, in place of bright vanity lights, to use while brushing your teeth before bed. When sleeping, keep the bedroom as dark as possible for the soundest sleep.

If someone is a lark, we use an alternate approach. Falling asleep early in the evening and awakening before sunrise, a lark is often an elder, although a small percentage of younger people fit this rhythm. Light therapy is used with a different schedule to shift the lark circadian rhythm. Upon arising, the light levels are kept low, including filtering blue light, thus sustaining melatonin levels for those predawn hours. If the lark engages in early morning outdoor activities or a morning commute, sunglasses are essential. Late in the afternoon and into the early evening, bright light is used to keep melatonin levels from building. This will often shift the lark’s schedule closer to the desired rhythm.

Exercise

A commitment to movement, especially if it is enough to get a little sweaty or elevate the heart rate—even slightly—helps us sleep better. Consider something that you can make a regular part of almost every day for twenty to thirty minutes. Movement and consistency, more so than the time of day or type of activity, are key. If gardening is pleasurable, let that be your sport. If the convenient time is in the evening, it is better for most to have the evening workout than to skip it due to worries that it is too close to bedtime. It may take several weeks to have an impact on sleep, but research suggests exercise increases sleep quality.

Nighttime Urination

There are several possible ways to eliminate nighttime urination. (This refers to people who interrupt their sleep to get up to urinate, as opposed to bedwetting, a different problem discussed in chapter 6.) Maybe you are thinking, “I only get up once during the night to urinate and go right back to sleep, so it isn’t a problem.” However, when we understand sleep architecture, the importance of its components, and how our eight hours of sleep must be uninterrupted in order to get the proper balance of each stage, we will see how even just one interruption each night can be a significant problem (see chapter 2). Let’s help people eliminate nighttime urination so they get the benefits of a full night’s sleep.

During the day, fluid accumulates in the legs in varying amounts depending on physical activity level. By elevating the legs during sitting and taking breaks to get movement in the legs, some of this fluid is moved from the legs up toward the kidneys to be urinated out during the day. Otherwise, upon lying down in bed at night, the fluid in the swollen legs, now elevated, moves up into the kidneys, producing more urine than the bladder can contain during the night. When working on a computer or watching television, prop up your legs above the level of your hips, being sure to provide support for the lower back (Figure 1.9). If sitting for long periods, get up occasionally, and while standing, lift the heels to put weight on the toes, then lift the toes so weight is on the heels. (Hold on to something if support is needed.) Repeating this several times helps move fluid out of the legs.

Fluid intake during the day and the evening has an impact on sleep. Stop drinking fluids ninety minutes before bed to give the kidneys time to filter the excess water from your blood. Then urinate immediately before bed to empty your bladder. For some people, herbal tea causes increased urination; however, in other people, it is no different than water. If you enjoy herbal tea before bed, determine if this is an influence by not drinking it within five hours of bed. After your nighttime urination is resolved, reintroduce the evening herbal tea and, if sleep is sound and uninterrupted, enjoy your tea (as long as it contains no caffeine). Alcohol also increases urination and is best avoided five hours before bed for this reason (and also due to its sleep architecture–disrupting properties). Eliminate caffeine entirely after noon, as it is a bladder irritant. Also examine nutritional supplements and any protein or workout powders to check for ingredients with diuretic effects.

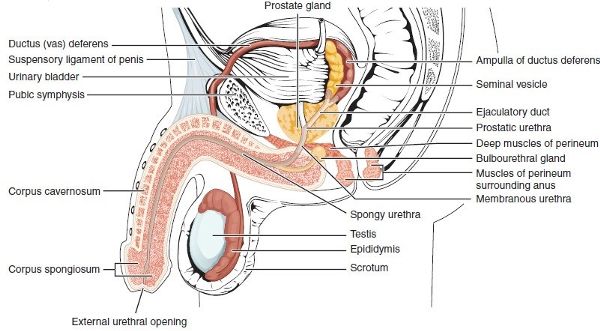

An enlarged prostate is associated with nighttime urination. This is a gland surrounding part of the male urethra, the tube that carries urine and semen (Figure 1.10). As men age, there is normal age-related prostate enlargement that squeezes the urethra to varying degrees. This makes it difficult to completely empty the bladder before bed, making it crucial to put all the other strategies in place to minimize the need to disrupt sleep for urination. Some men also decide to talk to their medical doctor regarding various prescription medications or surgical procedures to treat the symptoms.

If a person addresses the various concerns and is practicing all these strategies to eliminate nighttime urination but finds they are still getting up to urinate, there is a possibility that the nervous system is responding to a trigger of awakening—a snoring partner, an outdoor noise, a warm room—and perceiving a need to urinate even though the bladder is not full. Depending on a range of factors, including age, the bladder holds around two cups of urine and, for most people, even more at night. An easy way to determine if the bladder truly needs emptying is to collect the urine and measure the output. Upon arising in the middle of the night, urinate into a container such as a pitcher placed in the bathroom. In the morning, determine the volume of urine. If it is a small amount of urine, just a few ounces, perhaps the body and mind need to be trained to go back to sleep and not respond to the trigger to get up and urinate. However, if well over a cup of urine is produced after putting in place all the strategies mentioned, take this information to a doctor and discuss what could be causing the urine production. Knowing the amount of urine produced during the night will be helpful in the course of diagnostics.

If you still must urinate at night, be safe by lighting the way, and at the same time, preserve melatonin levels by using orange lights for illumination from bedside to the toilet.

Caffeine and Stimulants

Individual responses to caffeine vary widely, but if someone is getting poor sleep, advice about when to end consumption remains standard. Avoid caffeine in all its forms after noon until healthy sleep is achieved and sustained for at least a week. The same is true for guarana, a stimulant found in a range of sources, including energy drinks (Figure 1.11). Some folks need to give up caffeine, guarana, and any other stimulants (e.g., theobromine, which is found in chocolate) entirely until they get good sleep. After a satisfying sleep rhythm is maintained for a week, you could consider reintroducing stimulants. However, many will find getting good sleep for a week without stimulants provides such an increase in vitality that there is no need for any stimulants. If you are still craving a boost from caffeine or another stimulant, first reintroduce it before noon and notice if there are changes to sleep quality or the refreshed feeling upon awakening in the mornings. From there, determine the latest time in the day your body can clear out the caffeine/stimulant and allow you to sleep well at night.

Alcohol

Under the influence of alcohol, the brain is not able to construct a proper night’s sleep. Being relaxed and falling asleep is not the same as creating health-promoting sleep architecture (see chapter 2). For example, having as little as one serving of wine, beer, or spirits close to bedtime can cause increased awakenings during sleep (even though the person may not be aware of them), decreased rapid eye movement (REM) sleep in the first half of the night, and disturbing REM sleep rebound in the latter half. Alcohol on its own is not the challenge to sleep; rather it’s the timing of its consumption. Avoid alcohol at least five hours prior to bed so the sleep-disrupting chemicals get mostly metabolized out of the body before it’s time to tuck yourself in for the night. This is a wiser approach than the close to bedtime “nightcap” that is sure to hijack a sound night’s sleep.

Nicotine

The double bind of nicotine is that it is a stimulant that will keep us awake if used too close to bedtime, but if a person stops nicotine earlier in the evening, they will have subtle awakenings during the night due to nicotine withdrawals. However, the latter is preferable, so cease nicotine use at least five hours before bed.

To support sleep wellness and overall health, seek a local or online smoking cessation program, preferably one with scientifically proven mindfulness training, which has shown significant success. During the process of quitting, practice self-compassion for two reasons. The first is that smoking is one of the most difficult habits to change, so it is important to be kind to yourself throughout. The second is that neuroscience has proven that self-compassion is an effective component of habit-changing. Many communities have a resource such as the Hawaiʻi Quitline.4 Nationally in the US, there is also smokefree.gov or 1-800-QUIT-NOW (1-800-784-8669).

Nap

In the early afternoon, take a ten-to-twenty-minute nap. (See the napping section for details)

Medications

Sleep is disrupted by many medications, such as some antidepressants, over-the-counter sleep aids, pain medications, antihistamines, and even prescriptions marketed to promote sleep. Just because a medication puts someone to sleep does not mean it creates natural restorative sleep. Check with your health-care provider to determine whether any medications you take may impact your sleep and for guidance about pros and cons associated with sleep disruption and each course of treatment.

Sleep Diary

A sleep diary’s purpose goes well beyond keeping track of how you sleep. By keeping a good sleep diary, you will notice how daytime habits—exercise, alcohol, caffeine, TV viewing—and their timing have an impact on sleep. By keeping track of your sleep habits along with how you feel during the day, you will also establish a connection between sleep quality and daytime mood and performance. Record your data in a sleep diary for two weeks. In addition to providing clear motivation to make changes, this type of biofeedback also fuels the brain for habit-changing behavior. Use this fillable sleep diary5 created by one of my sleep science students at Kapiʻolani Community College. You may also try one of the many phone apps for tracking daytime activities and sleep quality. Daytime activity and mood data are essential to the process, so be sure whatever you use also tracks that information. People are often surprised by their findings after making use of a sleep diary. It shines a light on several potential areas for change to improve sleep.

Ritual

The brain can be rewired to associate behaviors and sensory input with falling asleep. Decide on a before-bed ritual, such as taking a shower, using a soothing naturally scented lotion, reading a book you read only at bedtime, meditating, singing, practicing a relaxing breathing technique, or listening to an audio book or podcast (Figure 1.12).

Leg Cramps

If you experience leg cramps at night, talk with your health-care practitioner to determine if you have any electrolyte imbalances or if they can suggest any supplements, vitamins, or electrolyte drinks. Maintain sufficient hydration. Incorporate daily exercise. Gentle early evening stretching, from head to toe, helps relieve lower leg cramps because they can be triggered by tension elsewhere (including up much higher) in the body. Consider a warm bath with Epsom salts (magnesium sulfate) before bed. During the cramp, applying an ice or heat pack or standing and holding a stretch might alleviate some of the pain.

Snack

Our tūtū (the way we say “grandparents” in Hawaiʻi) and tias (Spanish for “aunts”) knew what they were talking about when they advised us to have warm milk with honey before bed. Although there is a small amount of tryptophan in milk, which is associated with the cascade that puts us to sleep, and the carbohydrates in honey clear the way to allow more of the tryptophan to get into the brain, our sound sleep is probably more due to the calming ritual and the balanced nutrition of that bit of nourishment. The general guideline is to have a little snack close to bedtime and to include a small amount of fat and protein and balance that with carbohydrates, but no high-sugar items, which cause a stress response that keeps you awake. Examples of healthy bedtime snacks would be milk (can be dairy, almond, etc.) with whole-grain cereal (low in sugar) or nut butter with crackers (Figure 1.13). A small serving is best because digestion slows down with sleep. If you have gastroesophageal reflux disease, it is best to skip having food too close to lying down. Time it so it does not aggravate your symptoms.

Sleep in Bed

Use your bed only for sleeping, having sex, reading, or listening to a relaxing audio file. Avoid emailing, engaging in social media, or watching television in bed, all of which condition the brain to associate the bed with a different level of alertness, interfering with sleep. If you have spent what feels like twenty minutes trying to fall asleep, get out of bed, do something relaxing like reading a book on the couch or listening to a relaxing audiobook until sleepy, and then return to bed.

Temperature

While most people can sleep in a range of temperatures, I have had several clients find cooling the bedroom was the one thing needed to fix their sleep. Research shows the ideal sleeping temperature is a surprisingly cool 65–68 degrees Fahrenheit (18–20 degrees Celsius). In the wild, the natural drop in temperature each evening triggers the hypothalamus (see chapter 2) to launch the cascade that ultimately releases melatonin, telling our bodies it is time to sleep. Taking a warm bath or shower before bed promotes this cooling by bringing the blood flow to the skin in response to the heat. Then, after stepping out of the bath, the blood on the skin surface works like a radiator to cool the body temperature and send you into a relaxing sleep. To investigate this phenomenon, researchers developed a bodysuit with a layer containing a mesh of tiny tubes of water, precisely controlled for temperature and region of flow. When wearing the suit, participants’ skin surface was exposed to heat, yet remained dry. These experiments showed bringing blood flow to the body surface via temporary superficial warmth provided core-temperature body cooling and thus reduced the time participants needed to fall asleep and improved their sleep quality.6 Warming the feet and/or hands with a warm soak or heating pad is also a quick trick if taking a shower or bath is too time-consuming or not practical.

Timing

Most adults need around eight hours of sleep every night, and it is best to go to bed and get up in the morning at the same time each day, even on weekends.

Clocks

Do not have a clock within view of the bed; being aware of the time triggers a loop of thinking that keeps you awake. When awakening in the middle of the night, resist the urge to look at the clock or your phone (both of which should not be near your bed or visible) and train your brain to let go of the curiosity about the time.

Noise

If it is not possible to make the bedroom quiet, use noise-reducing earplugs. There are also phone apps and audio files that create relaxing white noise, such as rain sounds. Running a fan in the room is sometimes enough to mask intrusive noises. However, the brain still processes white noise information, so minimizing it is preferable when outside noises are low enough that you can still sleep.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI) involves meeting with an individual or a group once a week for four to eight weeks. The client is advised on how to change thoughts and behaviors to increase healthy sleep. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) claims CBTI is safe and effective.7 Many insurance companies cover CBTI, and research shows it is more effective than sleep medications. CBTI does not have medications’ harmful side effects and also has been shown to have beneficial effects extending beyond the treatment period, which is not the case with medications. One of the paradigms for CBTI involves five pillars: sleep wellness, sleep restriction, stimulus control, sleep diary, and actigraphy.

- 1. Sleep wellness: Refer to the Sleep Wellness Guide for instructions on this step.

- 2. Sleep restriction: Research shows this works better than medications and has longer-lasting effects. In general, the concept is to be in bed only when sleeping and not to spend hours lying there trying to sleep. Here are the steps:

- a. Spend only five hours in bed. Figure out what time you have to get up and count back five hours. Go to bed at the same time every night.

Example: Do you have to get up at 7:00 a.m.? Then go to bed at 2:00 a.m.

- b. After five days, you will be very tired in the evening due to sleep deprivation, but your circadian rhythm is closer to being set, so you can go to bed fifteen minutes earlier on that fifth night.

- c. After five more days, go to bed fifteen minutes earlier, and continue with this adjustment every five days until you are going to bed around eight hours before having to wake up.

During the program, a person may feel worse because they are so tired. Pay extra attention to light. Use dim or orange light at night and bright light in mornings.

Be safe. Put help in place before beginning. Do not do dangerous work, drive, take care of children, or anything else that requires your full attention to do safely in the early days of the program due to the high level of sleep debt.

- a. Spend only five hours in bed. Figure out what time you have to get up and count back five hours. Go to bed at the same time every night.

- 3. Stimulus control: A stimulus is something that causes a specific reaction. If you hear your phone (sound from phone = stimulus), you walk toward it (walking = response). Stimulus control involves separating sleep-related activities in the bedroom from wakeful activities in the rest of the home. For example, not watching TV, emailing in bed, or sleeping part of the night on the living room couch. Here are the instructions:

- a. If you are not sleepy, do not go to bed.

- b. If you cannot fall asleep within what feels like twenty minutes, leave the bedroom.

- c. Listen to an audiobook or do some gentle reading by a dim or blue light–filtered light in a chair or on the couch. Do not fall asleep there. When you start to fall asleep, move to your bed.

- d. Use the bed only for sleep, sex, and gentle reading or relaxing audio books.

- 4. Sleep diary: Refer to the sleep diary section in this chapter for instructions on this step. This helps pinpoint areas from the sleep wellness list that need to be addressed. For example, someone could report in their sleep diary that they were texting in bed or having a glass of wine before bed, but they did not realize those things could affect sleep.

- 5. Actigraphy: This is not necessary but can be helpful. Some clinicians use medical actigraphy devices, while laypersons might use mobile phone apps that monitor sleep. If using a phone app, temper your connection to the results and do not become fixated on the data, especially given the significant limitations of such phone apps as of the writing of this textbook. I have met people who became obsessed with their phone app sleep data to the point that it caused them anxiety and poor sleep. Also keep in mind that the movement of a sleeping partner may appear as your movement during a night’s recording, depending on the placement of your device and how easily movement is translated across your mattress. Both actigraphy and sleep-related phone apps use an accelerometer to detect changes in velocity, providing a record of physical activity. The movement patterns are processed by a computer algorithm that translates those movements as a state of sleep or waking. All this is in an attempt to verify four things:

- a. Circadian rhythmicity: Going to bed between 9:00 and 11:00 p.m. and getting out of bed early in the morning or around midmorning. These times are part of a healthy circadian rhythm.

- b. Consolidation: One major block of sleep, as opposed to something like three hours at midnight and three hours in the afternoon.

- c. Sleep schedule regularity: Going to bed and getting out of bed at the same every day.

- d. Napping: When and for how long the nap is taken.

Additional Support during Pregnancy

The National Sleep Foundation’s “Women and Sleep” poll in 1998 showed that 78 percent of women had more difficulty with sleep during pregnancy than any other time. Their 2007 follow-up survey indicated that the primary factors disturbing women’s sleep during pregnancy were getting up to urinate; back, neck, or joint pain; leg cramps; heartburn; and/or dreams. Even with all these challenges, there is good news, because most women can mitigate pregnancy-related sleep problems by implementing strategies listed in the Sleep Wellness Guide along with the following advice. This section will address the importance of sleep during pregnancy, and how to improve sleep by addressing challenges particular to pregnancy.

There are a range of reasons pregnant women are driven to be concerned about their sleep. Kathy Lee—a University of California, San Francisco, nursing professor and specialist on pregnancy and sleep—advises pregnant women to remember that in addition to “eating for two,” they are also “sleeping for two.” One of her studies reported that pregnant women who get less than six hours of sleep a night have more difficult labors and are over four times more likely to need a cesarean. A study by another group, which controlled for other factors associated with preterm birth, indicated that poor sleep during pregnancy is associated with a higher incidence of preterm birth (when a baby is born too early). Scientists suggest that preterm labor and births may be related to the increase in prostaglandins found in people getting inadequate sleep.

One of the disruptions to sleep in pregnancy is snoring. Because even a small increase in weight multiplies the chance of snoring, a woman who never snored could begin snoring during pregnancy, even with the minimal weight gain required. University of Michigan researchers recommend screening and treatment for this, as they found snoring that begins during pregnancy is associated with a higher risk of developing high blood pressure during the pregnancy (gestational hypertension) and preeclampsia. Hypertensive disorders during pregnancy can have serious consequences, so we must make an effort to educate people about the importance of screening pregnant women for snoring.

(Figure 1.14) ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Language of Hawaiʻi). Hāpai is Hawaiian for “pregnant.” It also means “to support and carry” .

Polls show that a small percentage of pregnant women drink alcohol before bed in hopes of improving their sleep, even though there is solid research on alcohol’s damaging effects to the fetus. Additionally, as stated earlier, while alcohol induces what feels like sleep, it is not healthy, normal sleep. It is essential for women to seek support to eliminate alcohol during pregnancy and lactation due to the damaging impact of alcohol on fetal and infant development. Infant sleep is significantly disrupted by even small amounts of alcohol in breast milk. If giving up alcohol during the breastfeeding months/years is not feasible, some people use different strategies like considering the timing of alcohol consumption and “pumping and dumping” breast milk until it is clear of alcohol before nursing. Please contact a lactation consultant or health-care provider for guidance.

Strategies for healthy sleep during pregnancy begin with the list of items on the Sleep Wellness Guide combined with these additional practices: Sleeping on the side, compared to on the back, reduces lower-back strain and takes the weight of the enlarging uterus off the large blood vessels vital to baby’s and mom’s circulation. This also is helpful for the digestive system, freeing it from the pressure of being beneath the uterus. As often as is comfortable, sleep on the left side, which is slightly preferred as it takes the weight of the uterus off the liver, which is on the right side of the body. Left-side sleep also provides the best position for blood flow to the heart and the rest of the body. Early in the pregnancy is a time to practice building the habit of sleeping on the side. However, sleeping all night on the side, especially the same side, is not necessary and likely would cause discomfort in the hips and shoulders. Remember that while this is the optimal position theoretically, the position itself is not something for the pregnant woman to worry about. The priority is to get sleep. During the night, you may awaken to find yourself on your back, or when falling asleep, you might feel better in something other than this prescribed side-sleeping position. Get comfortable as you wish, and rest assured that your body will give you a sign when a move is in order.

Here are some suggestions for increasing your comfort when side sleeping. Lying on your side, place a pillow between your bent knees and extend that pillow to the feet (Figure 1.15). The cushion between the knees squares the hip alignment, and its placement between the feet prevents the rotation of the top of the thigh bone (femur) in the hip socket. All this diminishes back strain. As the uterus increases in size, a cushion beneath the abdomen in this position is often comforting. Body-length pillows may also be a satisfying luxury. If you experience heartburn, use pillows to slightly elevate the head and shoulders in addition to following your health practitioner’s general heartburn treatments.

Regarding other common pregnancy-related sleep disturbances, see, for example, previous sections on treatment for frequent nighttime urination, leg cramps, and unsettling dreams. If there are still challenges, seek out a cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI) practitioner. CBTI is the most effective proven technique for insomnia and does not have the risks and side effects of medications.

Family Sleep and Bed Sharing

The baby has arrived—but now, where do they sleep? Babies sleeping in the same bed with parents is normal in a vast array of cultures all over the world, yet in the US, there continues to be fervent debate (Figure 1.16). Could it be our litigious society, where legal advisors caution medical groups against suggesting cosleeping on the off chance that something could go wrong, or are there legitimate safety and medical concerns? In the following discussion, the terms family sleep, family bed, bed sharing, and cosleeping will be used to refer to the practice of having a baby or child in the bed or in the immediate sleeping space of the parent.

Using research from the fields of medicine and anthropology, Dr. James McKenna, at the University of Notre Dame, provides resources to guide families in safe cosleeping practices. He emphasizes the need for an infant to be in contact with the mother’s body during sleep in order to properly regulate itself, as it did when in the womb. He is also very clear that bed sharing involves much thought, discussion, and a commitment from the parent and also the additional parent—if there is one—and that bed sharing is not suitable for everyone. A misperception associated with family sleep is that the child will grow to be clingy and more dependent, but sociologists and psychologists explain the opposite to be true. When a child senses the strong emotional bond of a parent, the child more easily grows to be independent and emotionally secure. One concept behind cosleeping is that it fosters an environment where a child more confidently differentiates from the parent.

Safe family sleeping requires certain precautions and arrangements such as these:

- • Infants should sleep on their back.

- • The sleeping surface must be firm and not a pillow.

- • The mattress should be as close to the floor as possible, preferably on the floor.

- • There must be no potential for a covering, such as a blanket or sheet, to fall over their face.

- • There must be no exposure to cigarette smoke or nicotine in utero or as an infant.

- • There must be no stuffed animals, pillows, or sheepskins (fluffy items).

- • Do not use water beds, beanbags, couches.

- • There must be no gap between the mattress and frame or the mattress and wall.

- • Parents must not use alcohol, drugs, or medication that may interfere with their ability to easily awaken.

- • Parents with long hair need to fix it so it cannot wrap around the baby’s neck.

- • Parents should ensure that they still experience a good night’s sleep. For parents who do not feel they will sleep well with the baby in the bed, there are certified-safe cosleeping bed attachments to consider.

- • Breastfeeding helps reduce death from SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome) and other diseases and is highly recommended in conjunction with cosleeping. If the baby is not sleeping with their breastfeeding parent or if the parent is extremely obese, it is safer for the baby to be on a separate surface from the parent’s bed, but still adjacent to it (such as in a cosleeping bed attachment).

Social Justice and Sleep Wellness

Who has the luxury of putting these sleep wellness practices in place? Who is able to dedicate eight hours each night to sleep when we have work and family responsibilities; go to school or work somewhere we can take a nap; make time for exercise; sleep in a comfortable bed in a dark, quiet room at the desired temperature? By now, you are likely clear on the importance of good sleep and its connection to how healthy you will be, how good you feel emotionally, and even how long you will live. But due to economic injustices and lack of equity around things like race and sexual orientation, many people cannot get adequate sleep. Please consider your part in working to help yourself and everyone get better sleep by reading “Your Next Actions for Justice” and chapter 7.

1 Daniel J. Buysse, “Sleep Health: Can We Define It? Does It Matter?,” Sleep 37, no. 1 (January 2014): 9–17, https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.3298.

2 Gandhi Yetish et al., “Natural Sleep and Its Seasonal Variations in Three Pre-industrial Societies,” Current Biology 25, no. 21 (November 2015): 2862–68, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.046.

3 Shook, Sheryl, “Sleep Diary,” Google, accessed December 3, 2021, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1zigrkIEwmCLq5oMAkZ-bQIajdwhA9mQezfNAervgIoE/copy.

4 “Hawai‘i Tobacco Quitline,” accessed December 3, 2021, https://hawaii.quitlogix.org/en-US/.

5 Shook, Sheryl, “Sleep Diary,” Google, accessed December 3, 2021, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1zigrkIEwmCLq5oMAkZ-bQIajdwhA9mQezfNAervgIoE/copy.

6 Roy J. E. M. Raymann, Dick F. Swaab, and Eus J. W. Van Someren, “Cutaneous Warming Promotes Sleep Onset,” American Journal of Physiology: Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 288, no. 6 (June 2005): 1589–97, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00492.2004.

7 “NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults,” NIH Consensus and State-of-the-Science Statements 22, no. 2 (June 2005): 1–30, https://consensus.nih.gov/2005/insomniastatement.htm.