8.2: Intercultural Conflict Management

- Page ID

- 58206

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Managing Conflict Across Cultures

Rarely do the types of conflict stand alone. Most often, several types of conflict are found intertwined within each other and within the context itself. The actual situation in which the conflict happens can occur on the personal level, the societal level, and even the international level. How people choose to manage conflict depends on the type of conflict, the contexts that they occur within, and the relationship with the other person or people. For example, conflicts with close friends may be more discussion based in the United States, but more accommodating in Japan. Both are focused on preserving the harmony within the relationship. However, if the conflict takes place between acquaintances or strangers, where maintaining a relationship is not as important, the engagement or dynamic styles may come out. Considering all the variations in how people choose to deal with conflict, it’s important to distinguish between productive and destructive conflict as well as cooperative and competitive conflict.

- Destructive conflict leads people to make sweeping generalizations about the problem. Groups or individuals escalate the issues with negative attitudes. The conflict starts to deviate from the original issues, and anything in the relationship is open for examination or re-visiting. Participants try to jockey for power while using threats, coercion, and deception as polarization occurs. Leaders display militant, single-minded traits to rally their followers.

- Productive conflict features skills that make it possible to manage conflict situations effectively and appropriately. First the participants narrow the conflict to the original issue so that the specific problem is easier to understand. Next, the leaders stress mutually satisfactory outcomes and direct all their efforts to cooperative problem-solving.

- Competitive conflict promotes escalation. When conflicts escalate and anger peaks, our minds are filled with negative thoughts of all the grievances and resentments we feel towards others (Sillars et al., 2000). Conflicted parties set up self-reinforcing and mutually confirming expectations. Coercion, deception, suspicion, rigidity, and poor communication are all hallmarks of a competitive atmosphere. Research from Alan Sillars and colleagues found that during disputes, individuals selectively remember information that supports themselves and contradicts their partners, view their own communication more positively than their partners’, and blame partners for failure to resolve the conflict (Sillars, Roberts, Leonard, & Dun, 2000). Sillars and colleagues also found that participant thoughts are often locked in simple, unqualified and negative views. Only in 2% of cases did respondents attribute cooperativeness to their partners and uncooperativeness to themselves (Sillars et al., 2000).

- Cooperative conflict promotes perceived similarity, trust, flexibility, and open communication. If both parties are committed to the resolution process, there is a sense of joint ownership in reaching a conclusion. Because it is very difficult to turn a competitive conflict relationship into a cooperative conflict relationship, a cooperative relationship must be encouraged from the very beginning before the conflict starts to escalate.

Conflict Resolution Styles

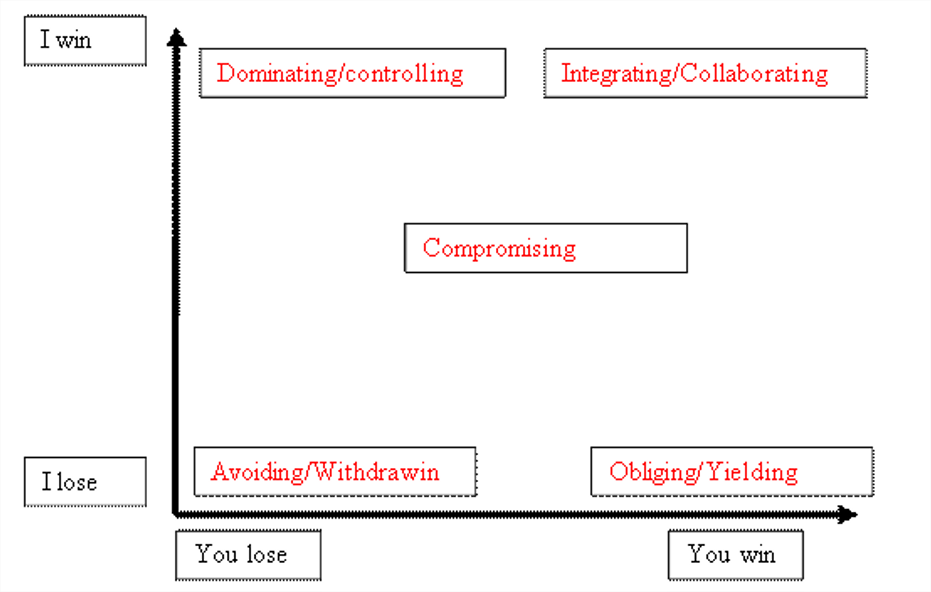

Conflict resolution styles represent processes and outcomes based on the interests of the parties involved. These are often presented in the form of a grid, as in the following (Baldwin, 2015b):

If I am intent on reaching my own goals in an encounter, I use what's called a dominating or controlling style. This is most often associated with cultures labeled individualistic, as it involves one individual's will winning over another's. On the other hand, if I am content to allow others to get their way, I use an obliging or yielding style. This is often related to cultures deemed collectivistic, as it favors harmony over outcome. Stella Ting-Toomey (2015) has been a leading scholar in this area, with explorations of how to predict a given conflict resolution style based on national cultures. But she cautions, as do others, how dependent individual behavior is on the specific context and on the willingness and ability of the parties to be flexible and compromising. Flexibility and openness might lead to the adoption of an integrating or collaborating approach, seeking to find a solution that satisfies both parties. A compromising approach provides a negotiated outcome which necessitates each party giving up something in order to reach a solution that provides partial gains on each side. Avoidance or withdrawal may be appropriate if no resolution is likely, or there is not enough time or information to resolve the conflict.

Individualism and Collectivism

The strongest cultural factor that influences your conflict approach is whether you belong to an individualistic or collectivistic culture (Ting-Toomey, 1997). People raised in collectivistic cultures often view direct communication regarding conflict as personal attacks (Nishiyama, 1971), and consequently are more likely to manage conflict through avoidance or accommodation. From a collectivistic perspective, the underlying goal in a conflict is not the preservation and manifestation of individual rights and attributes, but rather the preservation of relationships. In this approach, individual rights are superseded by group interest.

The predominant perspective of individualism is to have one's own ideas, and act according to the courage of one's convictions. Any perceived constraint on individual freedom is likely to pose immediate problems and require a response. Typically the most appropriate response in a conflict situation involves a direct or honest expression of one's ideas. People from individualistic cultures feel comfortable agreeing to disagree, and don’t particularly see such clashes as personal affronts (Ting-Toomey, 1985). They are more likely to assert their own position in a conflict, rather than seeking compromise or accommodation.

Gudykunst & Kim (2003) suggest that if you are an individualist in a dispute with a collectivist, you should consider the following:

- Recognize that collectivists may prefer to have a third party mediate the conflict so that those in conflict can manage their disagreement without direct confrontation to preserve relational harmony.

- Use more indirect verbal messages.

- Let go of the situation if the other person does not recognize the conflict exists or does not want to deal with it.

If you are a collectivist and are conflicting with someone from an individualistic culture, the following guidelines may help:

- Recognize that individualists often separate conflicts from people. It’s not personal.

- Use an assertive style, filled with “I” messages, and be direct by candidly stating your opinions and feelings.

- Manage conflicts even if you’d rather avoid them.

Effective conflict resolution serves all parties and preserves harmony. In cross-cultural situations, many scholars advocate the use of face negotiation techniques, as outlined below.

Face

The concept of face, often defined as a person's self-image or the amount of respect or accommodation a person expects to receive during interactions with others, plays a crucial role in navigating intercultural conflict. Conflict Face-Negotiation Theory (Ting-Toomey, 2004) examines the extent to which face is negotiated within a culture and what existing value patterns shape culture members’ preferences for the process of negotiating face in conflict situations. According to the theory, there are three different concepts of face:

- Self-face: The concern for one's image, the extent to which we feel valued and respected.

- Other-face: Our concern for the other's self-image, the extent to which we are concerned with the other's feelings.

- Mutual-face: Concern for both parties' face and for a positive relationship developing out of the interaction.

According to face negotiation theory, people in all cultures share the need to maintain and negotiate face. Some cultures – and individuals – tend to be more concerned with self-face, often associated with individualism. Individualistic cultures prefer a direct way of addressing conflicts, according to the chart presented earlier, a dominating style or, optimally, a collaborating approach. Addressing a conflict directly is something which particular cultures or people may prefer not to do. Conflict resolution in this case may become confrontational, leading potentially to a loss of face for the other party. Collectivists – cultures or individuals – tend to be more concerned with other-face and may prefer an indirect approach, using subtle or unspoken means to deal with conflict (avoiding, withdrawing, compromising), so as not to challenge the face of the other.

The term facework refers to the communication strategies that people use to establish, sustain, or restore a preferred social identity during an interaction with others. Goffman (1959) claims that everyone is concerned about how others perceive them. To lose face is to publicly suffer a diminished self-image, and saving face is to be liked, appreciated, and approved by others. Facework varies from culture to culture and influences conflict styles. Accounting for these differences, Conflict Face-Negotiation Theory recommends a four-skills approach to managing conflict across cultures. These skills are:

- Mindful Listening: Pay special attention to the cultural and personal assumptions being expressed in the conflict interaction. Paraphrase verbal and nonverbal content and emotional meaning of the other party’s message to check for accurate interpretation.

- Mindful Reframing: This is another face-honoring skill that requires the creation of alternative contexts to shape our understanding of the conflict behavior.

- Collaborative Dialog: An exchange of dialog that is oriented fully in the present moment and builds on Mindful Listening and Mindful Reframing to practice communicating with different linguistic or contextual resources.

- Culture-based Conflict Resolution Steps is a seven-step conflict resolution model that guides conflicting groups to identify the background of a problem, analyze the cultural assumptions and underlying values of a person in a conflict situation, and promotes ways to achieve harmony and share a common goal.

- What is my cultural and personal assessment of the problem?

- Why did I form this assessment and what is the source of this assessment?

- What are the underlying assumptions or values that drive my assessment?

- How do I know they are relative or valid in this conflict context?

- What reasons might I have for maintaining or changing my underlying conflict premise?

- How should I change my cultural or personal premises into the direction that promotes deeper intercultural understanding?

- How should I adapt on both verbal and nonverbal conflict style levels in order to display facework sensitive behaviors and to facilitate a productive common-interest outcome?

(Ting-Toomey, 2012; Fisher-Yoshida, 2005; Mezirow, 2000)

Conclusion

Despite our best intentions as well as engaging in the techniques for optimizing cross-cultural encounters, conflict is sometimes unavoidable. Scholars of conflict resolution have in fact pointed to some positive aspects of personal conflict (see sidebar). Conflicts can illuminate key cultural differences and thus can offer "rich points" for understanding other cultures.

What is conflict good for?

Conflict has many positive functions. It prevents stagnation, it stimulates interest and curiosity. It is the medium through which problems can be aired and solutions arrived at. It is the root of personal and social change. And conflict is often part of the process of testing and assessing oneself. As such it may be highly enjoyable as one experiences the pleasure of the full and active use of one's capacities. In addition, conflicts demarcate groups from one another and help establish group and personal identities.

-Deutsch, 1987, p. 38

Contributors and Attributions

Intercultural Communication for the Community College, by Karen Krumrey-Fulks. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

Language and Culture in Context: A Primer on Intercultural Communication, by Robert Godwin-Jones. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC

Communication in the Real World: An Introduction to Communication Studies, by No Attribution- Anonymous by request. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC-SA