10.1: The Importance of Listening

- Page ID

- 53888

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Define active listening and list the five stages of the listening process

- Illustrate the relationship between critical thinking and listening

- Give examples of the four main barriers to effective listening

Listening is an active process by which we make sense of, assess, and respond to what we hear.

Listening Is More than Just Hearing

Listening is a skill of critical significance in all aspects of our lives–from maintaining our personal relationships, to getting our jobs done, to taking notes in class, to figuring out which bus to take to the airport. Regardless of how we’re engaged with listening, it’s important to understand that listening involves more than just hearing the words that are directed at us. Listening is an active process by which we make sense of, assess, and respond to what we hear.

The listening process involves five stages: receiving, understanding, evaluating, remembering, and responding. These stages will be discussed in more detail in later sections. Basically, an effective listener must hear and identify the speech sounds directed toward them, understand the message of those sounds, critically evaluate or assess that message, remember what’s been said, and respond (either verbally or nonverbally) to information they’ve received.

Effectively engaging with all five stages of the listening process lets us best gather the information we need from the world around us.

Active Listening

Active listening is a particular communication technique that requires the listener to provide feedback on what he or she hears to the speaker, by way of restating or paraphrasing what they have heard in their own words. The goal of this repetition is to confirm what the listener has heard and to confirm the understanding of both parties. The ability to actively listen demonstrates sincerity, and that nothing is being assumed or taken for granted. Active listening is most often used to improve personal relationships, reduce misunderstanding and conflicts, strengthen cooperation, and foster understanding.

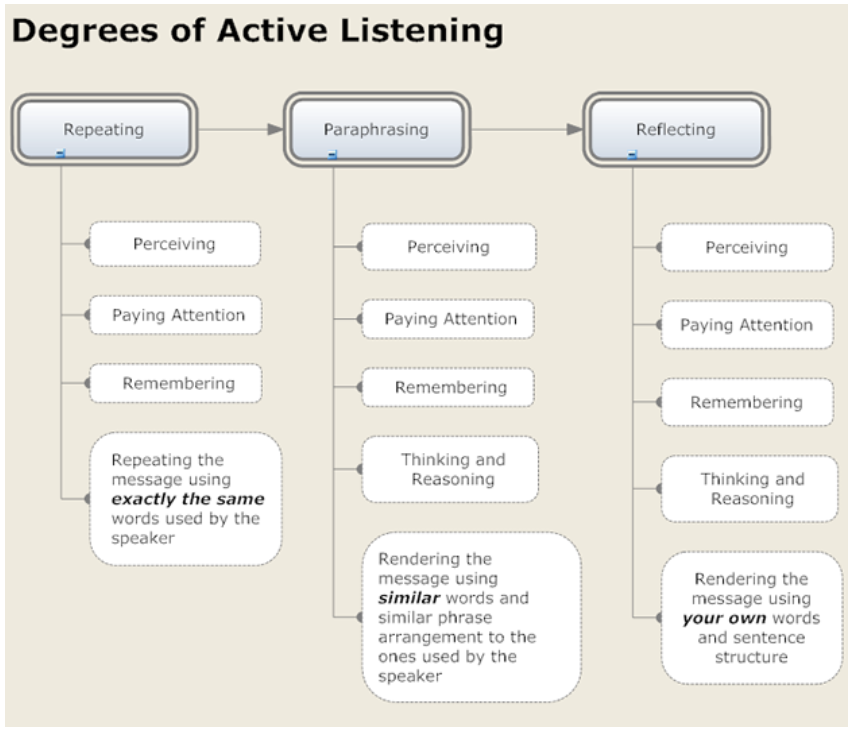

When engaging with a particular speaker, a listener can use several degrees of active listening, each resulting in a different quality of communication with the speaker. This active listening chart shows three main degrees of listening: repeating, paraphrasing, and reflecting.

Degrees of Active Listening

There are several degrees of active listening.

Active listening can also involve paying attention to the speaker’s behavior and body language. Having the ability to interpret a person’s body language lets the listener develop a more accurate understanding of the speaker’s message.

Listening and Critical Thinking

Critical thinking skills are essential and connected to the ability to listen effectively and process the information that one hears.

Critical Thinking

One definition for critical thinking is “the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. ”

In other words, critical thinking is the process by which people qualitatively and quantitatively assess the information they have accumulated, and how they in turn use that information to solve problems and forge new patterns of understanding. Critical thinking clarifies goals, examines assumptions, discerns hidden values, evaluates evidence, accomplishes actions, and assesses conclusions.

Critical thinking has many practical applications, such as formulating a workable solution to a complex personal problem, deliberating in a group setting about what course of action to take, or analyzing the assumptions and methods used in arriving at a scientific hypothesis. People use critical thinking to solve complex math problems or compare prices at the grocery store. It is a process that informs all aspects of one’s daily life, not just the time spent taking a class or writing an essay.

Critical thinking is imperative to effective communication, and thus, public speaking.

Connection of Critical Thinking to Listening

Critical thinking occurs whenever people figure out what to believe or what to do, and do so in a reasonable, reflective way. The concepts and principles of critical thinking can be applied to any context or case, but only by reflecting upon the nature of that application. Expressed in most general terms, critical thinking is “a way of taking up the problems of life. ” As such, reading, writing, speaking, and listening can all be done critically or uncritically insofar as core critical thinking skills can be applied to all of those activities. Critical thinking skills include observation, interpretation, analysis, inference, evaluation, explanation, and metacognition.

Critical thinkers are those who are able to do the following:

- Recognize problems and find workable solutions to those problems

- Understand the importance of prioritization in the hierarchy of problem solving tasks

- Gather relevant information

- Read between the lines by recognizing what is not said or stated

- Use language clearly, efficiently, and with efficacy

- Interpret data and form conclusions based on that data

- Determine the presence of lack of logical relationships

- Make sound conclusions and/or generalizations based on given data

- Test conclusions and generalizations

- Reconstruct one’s patterns of beliefs on the basis of wider experience

- Render accurate judgments about specific things and qualities in everyday life

Therefore, critical thinkers must engage in highly active listening to further their critical thinking skills. People can use critical thinking skills to understand, interpret, and assess what they hear in order to formulate appropriate reactions or responses. These skills allow people to organize the information that they hear, understand its context or relevance, recognize unstated assumptions, make logical connections between ideas, determine the truth values, and draw conclusions. Conversely, engaging in focused, effective listening also lets people collect information in a way that best promotes critical thinking and, ultimately, successful communication.

Causes of Poor Listening

Listening is negatively affected by low concentration, trying too hard, jumping ahead, and/or focusing on style instead of substance.

The act of “listening” may be affected by barriers that impede the flow of information. These barriers include distractions, an inability to prioritize information, a tendency to assume or judge based on little or no information (i.e., “jumping to conclusions), and general confusion about the topic being discussed. Listening barriers may be psychological (e.g., the listener’s emotions) or physical (e.g., noise and visual distraction). However, some of the most common barriers to effective listening include low concentration, lack of prioritization, poor judgement, and focusing on style rather than substance.

Low Concentration

Low concentration, or not paying close attention to speakers, is detrimental to effective listening. It can result from various psychological or physical situations such as visual or auditory distractions, physical discomfort, inadequate volume, lack of interest in the subject material, stress, or personal bias. Regardless of the cause, when a listener is not paying attention to a speaker’s dialogue, effective communication is significantly diminished. Both listeners and speakers should be aware of these kinds of impediments and work to eliminate or mitigate them.

When listening to speech, there is a time delay between the time a speaker utters a sentence to the moment the listener comprehends the speaker’s meaning. Normally, this happens within the span of a few seconds. If this process takes longer, the listener has to catch up to the speaker’s words if he or she continues to speak at a pace faster than the listener can comprehend. Often, it is easier for listeners to stop listening when they do not understand. Therefore, a speaker needs to know which parts of a speech may be more comprehension intensive than others, and adjust his or her speed, vocabulary, and sentence structure accordingly.

Lack of Prioritization

Just as lack of attention to detail in a conversation can lead to ineffective listening, so can focusing too much attention on the least important information. Listeners need to be able to pick up on social cues and prioritize the information they hear to identify the most important points within the context of the conversation.

Often, the information the audience needs to know is delivered along with less pertinent or irrelevant information. When listeners give equal weight to everything they hear, it makes it difficult to organize and retain the information they need. For instance, students who take notes in class must know which information to writing down within the context of an entire lecture. Writing down the lecture word for word is impossible as well as inefficient.

Poor Judgement

When listening to a speaker’s message, it is common to sometimes overlook aspects of the conversation or make judgments before all of the information is presented. Listeners often engage in confirmation bias, which is the tendency to isolate aspects of a conversation to support one’s own preexisting beliefs and values. This psychological process has a detrimental effect on listening for several reasons.

First, confirmation bias tends to cause listeners to enter the conversation before the speaker finishes her message and, thus, form opinions without first obtaining all pertinent information. Second, confirmation bias detracts from a listener’s ability to make accurate critical assessments. For example, a listener may hear something at the beginning of a speech that arouses a specific emotion. Whether anger, frustration, or anything else, this emotion could have a profound impact on the listener’s perception of the rest of the conversation.

Focusing on Style, Not Substance

The vividness effect explains how vivid or highly graphic an individual’s perception of a situation. When observing an event in person, an observer is automatically drawn toward the sensational, vivid or memorable aspects of a conversation or speech.

In the case of listening, distracting or larger-than-life elements in a speech or presentation can deflect attention away from the most important information in the conversation or presentation. These distractions can also influence the listener’s opinion. For example, if a Shakespearean professor delivered an entire lecture in an exaggerated Elizabethan accent, the class would likely not take the professor seriously, regardless of the actual academic merit of the lecture.

Cultural differences (including speakers’ accents, vocabulary, and misunderstandings due to cultural assumptions) can also obstruct the listening process. The same biases apply to the speaker’s physical appearance. To avoid this obstruction, listeners should be aware of these biases and focus on the substance, rather than the style of delivery, or the speaker’s voice and appearance.

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The listening process involves five stages: receiving, understanding, evaluating, remembering, and responding.

- Active listening is a particular communication technique that requires the listener to provide feedback on what he or she hears to the speaker.

- Three main degrees of active listening are repeating, paraphrasing, and reflecting.

- Critical thinking is the process by which people qualitatively and quantitatively assess the information they accumulate.

- Critical thinking skills include observation, interpretation, analysis, inference, evaluation, explanation, and metacognition.

- The concepts and principles of critical thinking can be applied to any context or case, including the process of listening.

- Effective listening lets people collect information in a way that promotes critical thinking and successful communication.

- Low concentration can be the result of various psychological or physical situations such as visual or auditory distractions, physical discomfort, inadequate volume, lack of interest in the subject material, stress, or personal bias.

- When listeners give equal weight to everything they hear, it makes it difficult to organize and retain the information they need. When the audience is trying too hard to listen, they often cannot take in the most important information they need.

- Jumping ahead can be detrimental to the listening experience; when listening to a speaker’s message, the audience overlooks aspects of the conversation or makes judgments before all of the information is presented.

- Confirmation bias is the tendency to pick out aspects of a conversation that support one’s own preexisting beliefs and values.

- A flashy speech can actually be more detrimental to the overall success and comprehension of the message because a speech that focuses on style offers little in the way of substance.

- Recognizing obstacles ahead of time can go a long way toward overcoming them.

Key Terms

- listening: The active process by which we make sense of, assess, and respond to what we hear.

- active listening: A particular communication technique that requires the listener to provide feedback on what he or she hears to the speaker.

- critical thinking: The process by which people qualitatively and quantitatively assess the information they have accumulated.

- Metacognition: “Cognition about cognition”, or “knowing about knowing. ” It can take many forms, including knowledge about when and how to use particular strategies for learning or for problem solving.

- confirmation bias: The tendency to pick out aspects of a conversation that support our one’s own preexisting beliefs and values.

- Vividness effect: The phenomenon of how vivid or highly graphic and dramatic events affect an individual’s perception of a situation.