6.5: Psychosocial Development in Middle Childhood - Self Concept and Self Efficacy

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 69395

As we consider psychosocial development in middle childhood, we need to first consider what our psychodynamic theorists proposed for this age group. After considering the views of Erikson and Freud, we'll consider the status of the self and the advanced in self understanding that we see in this age group.

Erik Erikson - Industry vs. Inferiority

Erik Erikson proposed that we are motivated by a need to achieve competence in certain areas of our lives. As we’ve learned in previous chapters, Erikson’s psychosocial theory has eight stages of development over the lifespan, from infancy through late adulthood. At each stage, there is a conflict, or task, that we need to resolve. Successful completion of each developmental task results in a sense of competence and a healthy personality. Failure to master these tasks leads to feelings of inadequacy.

During the middle childhood, children face the task of Industry versus Inferiority. Children begin to compare themselves to their peers to see how they measure up. They either develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in their schoolwork, sports, social activities, and family life, or they feel inferior and inadequate when they don’t measure up.

According to Erikson, children in middle childhood are very busy or industrious. They are constantly doing, planning, playing, getting together with friends, achieving. This is a very active time and a time when they are gaining a sense of how they measure up when compared with friends. Erikson believed that if these industrious children can be successful in their endeavors, they will get a sense of confidence for future challenges. If not, a sense of inferiority can be particularly haunting during middle childhood.

| Age | Period | Erikson's Psychosocial Task | Freud's Psychosexual Stage | Piaget's Cognitive Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | Infancy | Trust vs. Mistrust | Oral | Sensorimotor |

| 1–3 | Infancy/Toddlerhood | Autonomy vs. Shame/Doubt | Anal | Sensorimotor (0-2) Preoperational (2-7) |

| 3–6 | Early Childhood | Initiative vs. Guilt | Phallic | Preoperational |

| 7–11 | Middle Childhood | Industry vs. Inferiority | Latency | Concrete Operational |

Sigmund Freud - Psychoanalytic Theory

The great psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) focused on unconscious, biological forces that he felt shape individual personality. Freud (1933) thought that the personality consists of three parts: the id, the ego, and the superego. The id is the selfish part of the personality and consists of biological instincts that all babies have, including the need for food and, more generally, the demand for immediate gratification. As babies get older, they learn that not all their needs can be immediately satisfied and thus develop the ego, or the rational part of the personality. As children get older still, they internalize society’s norms and values and thus begin to develop their superego, which represents society’s conscience. If a child does not develop normally and the superego does not become strong enough, the individual is more at risk for being driven by the id to commit antisocial behavior.

Freud's developmental theory - his psychosexual stages - propose that we deal with inborn desires as we mature and how we resolve those desires impacts aspects of our personality. In middle childhood, we have the latency stage. This is effectively a pause, a break, between the gender issues resolved during the phallic stage - and the adult sexuality that ultimately develops during the genital stage.

Self-Concept

Children in middle childhood have a more realistic sense of self than do those in early childhood. Their self-descriptions are no longer focused on the physical and they have a sense of themselves as individuals with personalities and skills that exist within a social context. That exaggerated sense of self as “biggest” or “smartest” or “tallest” gives way to an understanding of one’s strengths and weaknesses. This can be attributed to greater experience in comparing one’s own performance with that of others and to greater cognitive flexibility. A child’s self-concept can be influenced by peers and family and the messages they send about a child’s worth. Contemporary children also receive messages from the media about how they "should" look and act. Movies, music videos, the internet, and advertisers can all create cultural images of what is desirable or undesirable and this, too, hold influence over a child’s self-concept.

The Tweens

According to Erikson, children in middle childhood are very busy or industrious. They are constantly doing, planning, playing, getting together with friends, achieving. This is a very active time and a time when they are gaining a sense of how they measure up when compared with friends. Erikson believed that if these industrious children can feel successful in their endeavors, they will gain a sense of confidence for many future challenges. If not, a sense of inferiority can be particularly haunting during middle childhood. Advertisers have certainly taken advantage of this age range by creating a new consumer group known as the “tweens” (for "in-between"). Tweens range in age from 8 to 12 years and are primarily targeted as consumers of media, clothing, and products that make them look “cool” and feel independent. For example, attitude t-shirts have been very popular among female tweens for the past several years and the slogans on these shirts reflect what might be considered “cool”. Here are a few found in a national retail clothing store that focuses on fashion for tweens.

- Your boyfriend gave me this shirt

- I live to shop

- It’s all about me

- You wish

In general, toys are not marketed to this age group as they once were. However, some toys designed to appeal to slightly younger children tend to sexualize children (Harmanci, 2006). Jean Kilbourne, a noted expert on the impact of advertising on self-image, responds to the promotion of such products as examples of how “marketers are hijacking our children’s sexuality” at the expense of childhood (Squire, 2006).

Self-Efficacy

What Is Self-Efficacy?

The term “self-efficacy” refers to your beliefs about your ability to effectively perform the tasks needed to attain a valued goal. Self-efficacy does not refer to your abilities, but to how strongly you believe you can use your abilities to work toward goals. Self-efficacy is not a single discrete construct or trait; rather, people have self-efficacy beliefs in different domains, such as academic self-efficacy, problem-solving self-efficacy, and self-regulatory self-efficacy. Stronger self-efficacy beliefs are associated with positive outcomes, such as academic fulfillment, greater activity satisfaction (such as athletics), happier relationships, and a healthier lifestyle. Note that the relationship here is correlational - which means strong self-efficacy beliefs appear to be related to positive outcomes, but we can't conclude a causal connection.

Imagine two students, Maria and Lucy, who are about to take the same math test. Maria and Lucy have the same exact ability to do well in math, the same level of intelligence, and the same motivation to do well on the test. They also studied together. They even have the same brand of shoes on. The only difference between the two is that Maria is very confident in her mathematical and her test-taking abilities, while Lucy is not. So, who is likely to do better on the test? Maria, of course, because she has the confidence to use her mathematical and test-taking abilities to deal with challenging math problems and to accomplish goals that are important to her—in this case, doing well on the test. This difference between Maria and Lucy—the student who got the A and the student who got the B-, respectively—is self-efficacy. As you will read later, self-efficacy influences behavior and emotions in particular ways that help people better manage challenges and achieve valued goals.

A concept that was first introduced by Albert Bandura in 1977, self-efficacy refers to a person’s beliefs that they are able to effectively perform the tasks needed to attain a valued goal (Bandura, 1977). Since then, self-efficacy has become one of the most thoroughly researched concepts in psychology. Just about every important domain of human behavior has been investigated using self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1997; Maddux, 1995; Maddux & Gosselin, 2011). Self-efficacy does not refer to your abilities but rather to your beliefs about what you can do with your abilities. Also, self-efficacy is not a trait—there are not certain types of people with high self-efficacies and others with low self-efficacies (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). Rather, people have self-efficacy beliefs about specific goals and life domains. For example, if you believe that you have the skills necessary to do well in school and believe you can use those skills to excel, then you have high academic self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy may sound similar to a concept you may be familiar with already—self-esteem—but these are very different notions. Self-esteem refers to how much you like or “esteem” yourself—to what extent you believe you are a good and worthwhile person. Self-efficacy, however, refers to your self-confidence to perform well and to achieve in specific areas of life such as school, work, and relationships. Self-efficacy does influence self-esteem because how you feel about yourself overall is greatly influenced by your confidence in your ability to perform well in areas that are important to you and to achieve valued goals. For example, if performing well in athletics is very important to you, then your self-efficacy for athletics will greatly influence your self-esteem; however, if performing well in athletics is not at all important you to you, then your self-efficacy for athletics will probably have little impact on your self-esteem.

How Do We Measure Self-Efficacy?

Like many other concepts in psychology, self-efficacy is not necessarily measured in a straightforward manner and requires much thought to be measured accurately. Self-efficacy is unlike weight, which is simple to objectively measure by using a scale, or height, which is simple to objectively measure by using a tape measure. Rather, self-efficacy is an abstract concept you can’t touch or see. To measure an abstract concept like self-efficacy, we use something called a self-report measure. A self-report measure is a type of questionnaire, like a survey, where people answer questions usually with answers that correspond to numerical values that can be added to create an overall index of some construct. For example, a well-known self-report measure is the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). It asks questions like, “In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?” and “In the last month, how often have you been angered because of things that were outside of your control?” Participants answer the questions on a 1 through 5 scale, where 1 means “not often” and 5 means “very often.” Then all of the answers are summed together to create a total “stress” score, with higher scores equating to higher levels of stress. It is very important to develop tools to measure self-efficacy that take people’s subjective beliefs about their self-efficacy and turn them into the most objective possible measure. This means that one person’s score of 6 out of 10 on a measure of self-efficacy will be similar to another person’s score of 6 out of 10 on the same measure.

We will discuss two broad types of self-report measures for self-efficacy. The first category includes measures of general self-efficacy (e.g., Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995; Sherer et al., 1982). These scales ask people to rate themselves on general items, such as “It is easy for me to stick to my aims and accomplish my goals” and “I can usually handle whatever comes my way.” It is worthy to note that self-efficacy is not a global trait, so there are problems with lumping all types of self-efficacy together in one measure. Thus, the second category of self-efficacy measures includes task-specific measures of self-efficacy. Rather than gauge self-efficacy in general, these measures ask about a person’s self-efficacy beliefs about a particular task. There can be an unlimited number of these types of measures. Task-specific measures of self-efficacy describe several situations relating to a behavior and then ask the participant to write down how confidently that person feels about doing that behavior. For example, a measure of exercise self-efficacy would list a variety of situations where it can be hard to exercise—such as when feeling depressed, when feeling tired, and when you are with other people who do not want to exercise. Finally, a measure of children’s self-regulatory self-efficacy would include a variety of situations where it can be hard to resist impulses—such as controlling temper, resisting peer pressure to smoke cigarettes, and defying pressure to have unprotected sex. Most studies agree that the task-specific measures of self-efficacy are better predictors of behavior than the general measures of self-efficacy (Bandura, 2006).

What Are the Major Influences on Self-Efficacy?

Here are some terms to know: If someone who seems similar to you succeeds, then you may come to believe that you will succeed as well. In this course, this description is termed “vicarious performance.” When you do well and succeed at a particular task, to attain a valued goal, you usually believe that you will succeed again at this task. This is called a “performance experience.” “Verbal persuasion” involves people telling you what they believe you are and are not capable of doing. Not all people will be equally persuasive! What you imagine yourself doing and how well or poorly you imagine yourself doing it is called “imaginal performances.” “Affective states and physical sensations” is the term for when you associate negative moods and negative physical sensations with failure, and positive physical sensations with success.

Self-efficacy beliefs are influenced in five different ways (Bandura, 1997).

| Influence | Definition |

|---|---|

| Performance Experiences | When you do well and succeed at a particular task to attain a valued goal, you usually believe that you will succeed again at this task. When you fail you often expect that you will fail again in the future if you try that task. |

| Vicarious Performances | If someone who seems similar to you succeeds, then you may come to believe that you will succeed as well. |

| Verbal Persuasion | If someone who seems similar to you succeeds, then you may come to believe that you will succeed as well. |

| Imaginable Performances | What you imagine yourself doing and how well or poorly you imagine yourself doing it. |

| Affective States & Physical Sensations | When you associate negative moods and negative physical sensations with failure, and positive physical sensations with success. |

These five types of self-efficacy influence can take many real-world forms that almost everyone has experienced. You may have had previous performance experiences affect your academic self-efficacy when you did well on a test and believed that you would do well on the next test. A vicarious performance may have affected your athletic self-efficacy when you saw your best friend skateboard for the first time and thought that you could skateboard well, too. Verbal persuasion could have affected your academic self-efficacy when a teacher that you respect told you that you could get into the college of your choice if you studied hard for the SATs. It’s important to know that not all people are equally likely to influence your self-efficacy through verbal persuasion. People who appear trustworthy or attractive, or who seem to be experts, are more likely to influence your self-efficacy than are people who do not possess these qualities (Petty & Brinol, 2010). That’s why a teacher you respect is more likely to influence your self-efficacy than a teacher you do not respect. Imaginal performances are an effective way to increase your self-efficacy. For example, imagining yourself doing well on a job interview actually leads to more effective interviewing (Knudstrup, Segrest, & Hurley, 2003). Affective states and physical sensations abound when you think about the times you have given presentations in class. For example, you may have felt your heart racing while giving a presentation. If you believed your heart was racing because you had just had a lot of caffeine, it likely would not affect your performance. If you believed your heart was racing because you were doing a poor job, you might believe that you cannot give the presentation well. This is because you associate the feeling of anxiety with failure and expect to fail when you are feeling anxious.

When and How Does Self-Efficacy Develop?

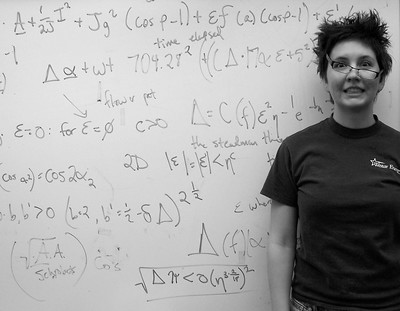

Figure 6.5.3: How does an effective coach impact self-efficacy? (CC0; NA via NA)

Our assessments of our own self-efficacy aren’t created in a vacuum. Those around us (such as our parents and our friends) greatly influence our perceptions of self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy begins to develop in very young children and is an important feature in middle childhood (and beyond). Once self-efficacy is developed, it does not remain constant though—it can change and grow as an individual has different experiences throughout their lifetime. When children are very young, their parents/caregivers self-efficacies are important (Jones & Prinz, 2005). Children of those with high parental/caregiver self-efficacies perceive them as more responsive to their needs (Gondoli & Silverberg, 1997).

What Are the Benefits of High Self-Efficacy?

Academic Achievement

Consider academic self-efficacy in your own life and recall the earlier example of Maria and Lucy. Are you more like Maria, who has high academic self-efficacy and believes that she can use her abilities to do well in school, or are you more like Lucy, who does not believe that she can effectively use her academic abilities to excel in school? Do you think your own self-efficacy has ever affected your academic ability? Do you think you have ever studied more or less intensely because you did or did not believe in your abilities to do well? Many researchers have considered how self-efficacy works in academic settings, and the short answer is that academic self-efficacy affects every possible area of academic achievement (Pajares, 1996).

Students who believe in their ability to do well academically tend to be more motivated in school (Schunk, 1991). When self-efficacious students attain their goals, they continue to set even more challenging goals (Schunk, 1990). This can all lead to better performance in school in terms of higher grades and taking more challenging classes (Multon, Brown, & Lent, 1991). For example, students with high academic self-efficacies might study harder because they believe that they are able to use their abilities to study effectively. Because they studied hard, they receive an A on their next test. Teachers’ self-efficacies also can affect how well a student performs in school. Self-efficacious teachers encourage parents/caregivers to take a more active role in their children’s learning, leading to better academic performance (Hoover-Dempsey, Bassler, & Brissie, 1987).

Much research exists about how self-efficacy is beneficial to school-aged children (middle childhood) but the benefits of self-efficacy continue beyond the school years: people with strong self-efficacy beliefs toward performing well in school tend to perceive a wider range of career options (Lent, Brown, & Larkin, 1986). In addition, people who have stronger beliefs of self-efficacy toward their professional work tend to have more successful careers (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998).

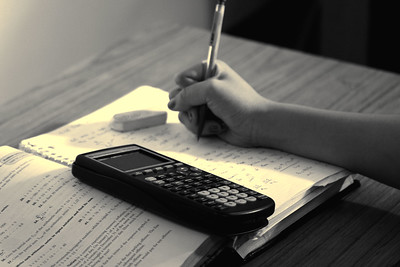

Figure 6.5.4: Consider getting a math problem you automatically believe you can’t solve. Will you even attempt to answer it? Our perception of self-efficacy affects our motivation to engage with challenges in the first place. (CC BY 2.0; Andrea Allen via Flickr]

One question you might have about self-efficacy and academic performance is how a student’s actual academic ability interacts with self-efficacy to influence academic performance. The answer is that a student’s actual ability does play a role, but it is also influenced by self-efficacy. Students with greater ability perform better than those with lesser ability. But, among a group of students with the same exact level of academic ability, those with stronger academic self-efficacies outperform those with weaker self-efficacies. One study (Collins, 1984) compared performance on difficult math problems among groups of students with different levels of math ability and different levels of math self-efficacy. Among a group of students with average levels of math ability, the students with weak math self-efficacies got about 25% of the math problems correct. The students with average levels of math ability and strong math self-efficacies got about 45% of the questions correct. This means that by just having stronger math self-efficacy, a student of average math ability will perform 20% better than a student with similar math ability but weaker math self-efficacy. You might also wonder if self-efficacy makes a difference only for people with average or below-average abilities. Self-efficacy is important even for above-average students. In this study, those with above-average math abilities and low math self-efficacies answered only about 65% of the questions correctly; those with above-average math abilities and high math self-efficacies answered about 75% of the questions correctly.

Self-Regulation

One of the major reasons that higher self-efficacy usually leads to better performance and greater success in numerous areas is that self-efficacy is an important component of self-regulation. Self-regulation is the complex process through which you control your thoughts, emotions, and actions (Gross, 1998). It is crucial to success and well-being in almost every area of your life. Every day, you are exposed to situations where you might want to act or feel a certain way that would be socially inappropriate or that might be unhealthy for you in the long run. For example, when sitting in a boring class, you might want to take out your phone and text your friends, take off your shoes and take a nap, or perhaps scream because you are so bored. Self-regulation is the process that you use to avoid such behaviors and instead sit quietly through class. Self-regulation takes a lot of effort, and it is often compared to a muscle that can be exhausted (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, & Tice, 1998). For example, a kid in middle childhood might be able to resist eating a pile of delicious cookies if they are in the room with the cookies for only a few minutes, but if that child were forced to spend hours with the cookies, their ability to regulate the desire to eat the cookies would probably wear down. Eventually, their self-regulatory abilities would be exhausted, and the child would eat the cookies. A person with strong self-efficacy beliefs might become less distressed in the face of failure than might someone with weak self-efficacy. Because self-efficacious people are less likely to become distressed, they draw less on their self-regulation reserves; thus, self-efficacious people persist longer in the face of a challenge.

Figure 6.55: Self-efficacy is all about your belief of control over your environment. But when cookies that look this good are nearby, you may feel like you have no control to resist eating one (or more). (CC0 Public Domain; NA via NA)

Figure 6.55: Self-efficacy is all about your belief of control over your environment. But when cookies that look this good are nearby, you may feel like you have no control to resist eating one (or more). (CC0 Public Domain; NA via NA)

Middle childhood is a fantastic period in the lifespan to expand and encourage self-efficacy because it influences self-regulation in many ways (Maddux & Volkmann, 2010). First, people with stronger self-efficacies have greater motivation to perform in the area for which they have stronger self-efficacies (Bandura & Locke, 2003). This means that people are motivated to work harder in those areas where they believe they can effectively perform. Second, people with stronger self-efficacies are more likely to persevere through challenges in attaining goals (Vancouver, More, & Yoder, 2008). For example, people with high academic self-efficacies are better able to motivate themselves to persevere through such challenges as taking a difficult class and completing their degrees because they believe that their efforts will pay off. Third, self-efficacious people believe that they have more control over a situation. Having more control over a situation means that self-efficacious people might be more likely to engage in the behaviors that will allow them to achieve their desired goal. Finally, self-efficacious people have more confidence in their problem-solving abilities and, thus, are able to better use their cognitive resources and make better decisions, especially in the face of challenges and setbacks (Cervone, Jiwani, & Wood, 1991).

Our own final words on self-efficacy also draw from children’s literature. Again, middle childhood is a wonderful time to expand and encourage self-efficacy and the book, Oh, The Places You’ll Go! by Dr. Seuss is all about self-efficacy. This book speaks directly to readers by talking about all of the challenges they might face on their journeys. Throughout the book, the narrator continues to assure readers that they will be able to use their abilities to effectively handle these challenges. So, we leave you with Dr. Seuss’ wise words: “You’re on your own. And you know what you know. And you are the one who’ll decide where to go…. And will you succeed? Yes! You will, indeed! 98 and 3/4 percent guaranteed.”

The Society of Children

Friendships, in middle childhood, take on new importance as judges of one’s worth, competence, and "attractiveness". Friendships provide the opportunity for learning social skills such as how to communicate with others and how to negotiate differences. Children get ideas from one another about how to perform certain tasks, how to gain popularity or avoid it, what to wear, say, and listen to, and how to act. This society of children marks a transition from a life focused on the family to a life concerned with peers. Peers play a key role in a child’s self-esteem at this age as any parent who has tried to console a rejected child will tell you. No matter how complimentary and encouraging the parent/caregiver may be, being rejected by friends can often (but not always!) only be remedied by renewed acceptance.

Peer Relationships: Most children want to be liked and accepted by their friends. At this stage, children are sometimes identified by the ways in which they navigate peer connections, which can have a host of implications as you can imagine. Here, we take a brief look at some of the different styles children may use in peer connections: Some children are deemed popular by others and are described to be consistently kind to others and have stronger social skills. These "popular-prosocial" children tend to do well in school and are usually seen as cooperative and friendly. Another "popular" style is the "popular-antisocial" children who may gain popularity by acting tough or spreading rumors about others (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004). Other styles exhibited by children in middle childhood are those in the category of rejected children who are sometimes excluded because they are shy and withdrawn. The "withdrawn-rejected" children are easy targets for bullies because they are unlikely to retaliate when belittled (Boulton, 1999). Other rejected children are ostracized because they are aggressive, loud, and confrontational. The "aggressive-rejected" children may be acting out of a feeling of insecurity. Unfortunately, their fear of rejection can lead to behaviors that brings further rejection from other children. Children who are not accepted are more likely to experience conflict, lack confidence, and have trouble adjusting.

References and Attributions

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares & T. C. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 307–337). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A., & Locke, E. A. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 87–99. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.87

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252–1265. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1252

Cervone, D., Jiwani, N., & Wood, R. (1991). Goal setting and the differential influence of self-regulatory processes on complex decision-making performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 257–266.

Cillessen, A.H.N. and Mayeux, L. (2004), From Censure to Reinforcement: Developmental Changes in the Association Between Aggression and Social Status. Child Development, 75: 147-163. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00660.x

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385. doi:10.2307/2136404

Collins, J. L. (1984). Self-efficacy and ability in achievement behavior. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University.

Gondoli, D. M., & Silverberg, S. B. (1997). Maternal emotional distress and diminished responsiveness: The mediating role of parenting efficacy and parental perspective taking. Developmental Psychology, 33(5), 861–868.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271.

Harmanci, R. (2006, December 17). Sex inuendo: Under the tree over the punch bowl. Cultural shift: Little girls, sexy dolls-toy industry markets to 'Kids growing older younger. Retrieved January 3, 2007, from www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/articl...Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Bassler, O. C., & Brissie, J. S. (1987). Parent involvement: Contributions of teacher efficacy, school socioeconomic status, and other school characteristics. American Educational Research Journal, 24(3), 417–435. doi:10.3102/00028312024003417

Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341–363. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004

Knudstrup, M., Segrest, S. L., & Hurley, A. E. (2003). The use of mental imagery in the simulated employment interview situation. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(6), 573–591. doi:10.1108/02683940310494395

Maddux, J. E. & Kleiman, E. (2020). Self-efficacy. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/bmv4hd6p (CC BY-NC-SA)

Maddux, J. E., & Gosselin, J. T. (2011). Self-efficacy. In D. S. Dunn (Ed.), Oxford bibliographies online: Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press. Retrived from: http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/...abi&result=105

Maddux, J. E., & Volkmann, J. R. (2010). Self-efficacy and self-regulation. In R. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of personality and self-regulation (315-321). New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Multon, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991). Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic outcomes: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38(1), 30–38. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.38.1.30

Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of Educational Research, 66(4), 543–578. doi:10.3102/00346543066004543.

Petty, R., & Brinol, P. (2010). Attitude change. In R. F. Baumeister & E. J. Finkel (Eds.), Advanced social psychology: The state of the science. Oxford University Press.

Schunk, D. H. (1991). Self-efficacy and academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 26(3–4), 207–231. doi:10.1080/00461520.1991.9653133

Schunk, D. H. (1990). Goal setting and self-efficacy during self-regulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 25(1), 71–86. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2501_6

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs, 1, 35–37.

Seuss, Dr. (1990). Oh, the places you’ll go! New York: Random House.

Sherer, M., Maddux, J.E., Mercadante, B., Prentice Dunn, S., Jacobs, B., & Rogers, R.W. (1982). The self efficacy scale: Construction and validation. Psychological Reports, 51, 663–671.

Squire, R. (2006, November 3). Marketers hijack sexuality: Expert decries young girls' loss of childhood. Winnipeg Sun. Retrieved January 3, 2007, from www.jeankilbourne.com/news.htm.

Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 240–261. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.240

Vancouver, J. B., More, K. M., & Yoder, R. J. (2008). Self-efficacy and resource allocation: Support for a discontinuous model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 35-47. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.35.