Sociological Research

- Page ID

- 255446

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Approaches to Knowledge

The Scientific Method

The Scientific Method is an ongoing process. Each step feeds the next step. How is this different from a linear model you may have previously learned about?

"The Scientific Process" by Michaela Willi Hooper and Jennifer Puentes, Open Oregon Educational Resources (2022), is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This image displays a page in a geography book published in 1864. 'Scientists' for centuries used illegitimate pseudo-scientific methods to exaggerate physical differences between social groups and to attempt to position Western European white men as superior to everyone else.

"A geography for beginners" by K.J. Stewart via Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain

The Interpretive Framework

Rather than starting with a hypothesis, in the Interpretive Framework you start with a topic and ask people about it. As you look at the interview data, themes emerge. How is this model different from the scientific method?

No photo credit provided

Indigenous Frameworks

Our research has shown us that Indigenous sciences and foundational principles have the power to heal and rebalance in this world, as well as to address serious illness. Our intent is to open a pathway that would allow for this knowledge and understanding to safely and respectfully be introduced – or in some cases reintroduced – to the world through science.

– Joseph American Horse, leader of the Oglala Lakota Oyate

Scholar Gregory Cajete, a Tewa Indian from Santa Clara Pueblo in New Mexico, articulates the differences between Indigenous and Western ways of doing science.

“Photo of Gregory Cajete” © Gregory Cajete is all rights reserved and included with permission

Biologist and storyteller Robin Wall Kimmerer reflects on the difference between naming and classifying in the Western scientific tradition and understanding relationships in the Indigenous traditions in this video, "Consider This with Robin Wall Kimmerer [YouTube]" (watch from 55:25 to 57:20).

“Consider This with Robin Wall Kimmerer” by Oregon Humanities is licensed under the Standard YouTube License

Horses are an active part of life for the Lakota and many other Plains nations today. How does learning more about the Indigenous history of the horse challenge the ways of Western science?

“Image” © Jacquelyn Córdova/Northern Vision Productions is included under fair use

Sociological Research Methods

Social scientists have many ways to collect the data to research their questions and allow them to explain and predict the social world. The ways in which social scientists collect, analyze, and understand research information are called research methods. These research methods define how we do social science. Sound research is an essential tool for understanding the sources, dynamics, and consequences of social problems and possible solutions to them.

In this section, we examine some of the most common research methods. Research methods are often grouped into two categories: quantitative research, data collected in numerical form that can be counted and analyzed using statistics, and qualitative research, non-numerical, descriptive data that is often subjective and based on what is experienced in a social setting. From the table and discussion below, surveys and experiments are quantitative studies, whereas field research and in-depth interviews are qualitative studies. Some of the strongest scientific studies combine both approaches. New research methods go beyond the two categories, exploring international and Indigenous knowledge or doing research for the purpose of taking action.

The Major Sociological Research Methods Snapshot table below summarizes the methods and some of their advantages and disadvantages.

| Method | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surveys | Collects answers from many subjects who are asked a variety of questions, and analyzes the responses with statistics. | Many people can be included. If given to a random sample of the population, a survey’s results can be generalized to the population. | Large surveys are expensive and time-consuming. Although much information is gathered, this information is relatively superficial. |

| Experiments | Compares an experimental group who is exposed to the independent variable with a control group who is not exposed, and analyzes the differences. | If random assignment is used, experiments provide fairly convincing data on cause and effect. | Because experiments do not involve random samples of the population and most often involve college students, their results cannot readily be generalized to the population. |

|

Observations / field research |

Observes individuals and groups in their natural social setting, and analyzes the extensive field notes. | Observational studies may provide rich, detailed information about the people who are observed. | Because observation studies do not involve random samples of the population, their results cannot readily be generalized to the population. |

| In-depth interviews | Conducts many face-to-face (or online or phone) interviews with participants, and analyzes the transcriptions. | Interviewing people provides in-depth knowledge on how they understand or experience a social phenomenon. | Interviews are time-consuming to conduct as each may be 30 minutes to a few hours in length, and they are time-consuming to transcribe without quality software. |

| Secondary data | Analyzes existing data (does not collect original data to analyze) | Because existing data have already been gathered, the researcher does not have to spend the time and money to gather data. | The data set that is being analyzed may not contain data on all the variables in which a sociologist is interested or may contain data on variables that are not measured in ways the sociologist prefers. |

Surveys

Surveys are very useful for gathering various kinds of information relevant to social problems. Advances in technology have made telephone surveys involving random-digit dialing perhaps the most popular way of conducting a survey.

Plantronicsgermany – Encore520 call center man standing – CC BY-ND 2.0

Experiments

In this field experiment, researchers investigated whether employers would discriminate against applicants with foreign names. The researchers found that if the application was from Brian instead of Boleslav, the person was twice as likely to get a job interview. What other indicators of social location might influence hiring?

“Image of Boleslav Makarey Experiment” from Seven Examples of Field Experiments for Sociology © Revise Sociology is included under fair use

Observational Studies

In-depth Interviews

In-depth interviewing is sometimes referred an 'art' because the researcher must be skilled enough to establish rapport and maintain a conversational tone in each interview, to help the participant build trust and feel comfortable answering questions.

"Women In Tech - 82" by WOCinTech Chat via flickr is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Secondary Data

International Research

Action Research

Humanitarian Efforts

Community-Based Action Research

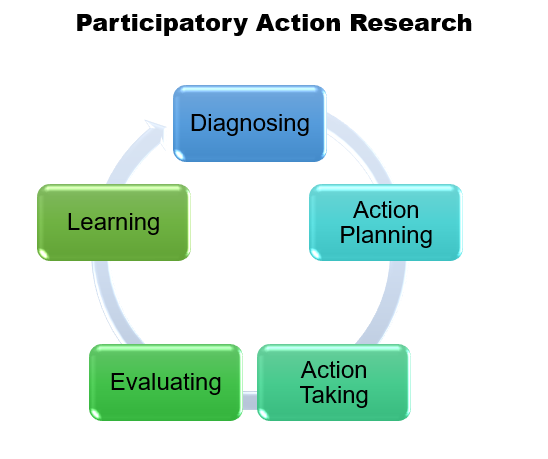

The action research cycle is a continuous process in which the researcher and the community learn about the social problem, figure out a root cause or diagnosis, plan an action that will impact the root cause, take action or make the change, evaluate the results, and continue to learn more. How is this cycle different from the scientific method we examined earlier?

“Action Research Cycle” from “Interpretive Research” by Anol Bhattacherjee, Social Science Research: Principles, Methods and Practices (Revised edition) is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The research is rigorous and often published in professional reports and presented to the board of directors for the organization you action research. As it sounds, action research suggests that we make a plan to implement changes. Often with academic research, we aim to learn more about a population and leave the next steps up to others. This is an important part of the puzzle, as we need to start with knowledge. Still, action research often aims to fix something or at least quickly translate the newly acquired findings into a solution for a social problem.

Participatory action research involves the people that the researcher is studying in the study design and execution. Based on the results, organizations and people take action. As you watch this video, you might consider,” How might this increase social justice?”

“Participatory Action Research” with Shirah Haasan by Vera Institute of Justice is licensed under the Standard YouTube License

Community-based action research looks for evidence. As new insights emerge, the researchers adjust the question or the approach. This type of research engages people who have traditionally been referred to as subjects as active participants in the research process. The researcher is working with the organization during the whole process and will likely bring in different project design elements based on the organization’s needs. Social scientists can bring more formalized training, but they draw both on existing research/literature and the goals of the organization they are working with. Community-based research or participatory research can be considered an orientation for research rather than strictly a method. Often a number of different methods are used to collect data. Change is the purpose of the research.

––

Now that we have an understanding of the field of sociology including sociological research, sociological theoretical perspectives, and sociological concepts, we can begin to explore specific social problems as they relate to a variety of broad topics. We will start with poverty and economic inequality in the next chapter.