Education in the United States today is a massive social institution involving millions of people and billions of dollars. In the Fall of 2022, more than 75 million people, almost one-fourth of the US population, attend school at all levels. The great majority (nearly 50 million) were enrolled in public K-12 schools, and a smaller group (5.5 million) were enrolled in private K-12 schools. Over 18 million were enrolled in college, the postsecondary level (National Center for Education Statistics 2025).

The story of modern education is a story of a significant social shift. Most people across the globe can read and write, something that wasn’t true even a hundred years ago. Although men and boys historically have had more chances to go to school than women and girls, the gender gap in education is closing around the world (Roser & Ortiz-Espinosa 2016). Over the past few decades, women have become more and more likely to attend and complete college in the US than men (Hurst 2024), despite having been locked out of the institution historically. Equal access to education doesn't tell the whole story, though.

Educational Disparities

Our social locations greatly impact our chances of graduating from high school, going to college, and achieving a college degree. Educational attainment – how far one gets in school – depends heavily on family social class and race (Tavernise 2012), as well as other areas of social location such as disability.

When we examine how students perform in school, we see a difference between those who are affluent white boys or men and those who are not. We may examine whether students can read, write, reason critically, or use computers or whether they graduate from high school or attend college or graduate school. The achievement gap refers to any significant and persistent disparity in academic performance or educational attainment between different groups of students, such as white students and students of color, for example, or students from higher-income and lower-income households (Great Schools Partnership 2013).

In some good news, the gender achievement gap is closing. Colleges in the US enroll at least as many women as men and more women than men appear to be graduating (Parker 2021). (Note that reliable data are rarely available for nonbinary students.) However, differences in educational outcomes persist when you examine the trends using race and class, and girls and women experience unique challenges in education such as marginalization and harassment. Additionally, when you apply intersectional analysis to education, such as examining outcomes and experiences of disabled students of color, the differences in outcomes become even more pronounced.

Below we will provide a few examples of differences in educational attainment, or achievement gaps. We discuss these in the Overview page to offer a sense of the depth of educational disparities that exist in the US today, before turning to other issues of educational inequality in the Patterns page.

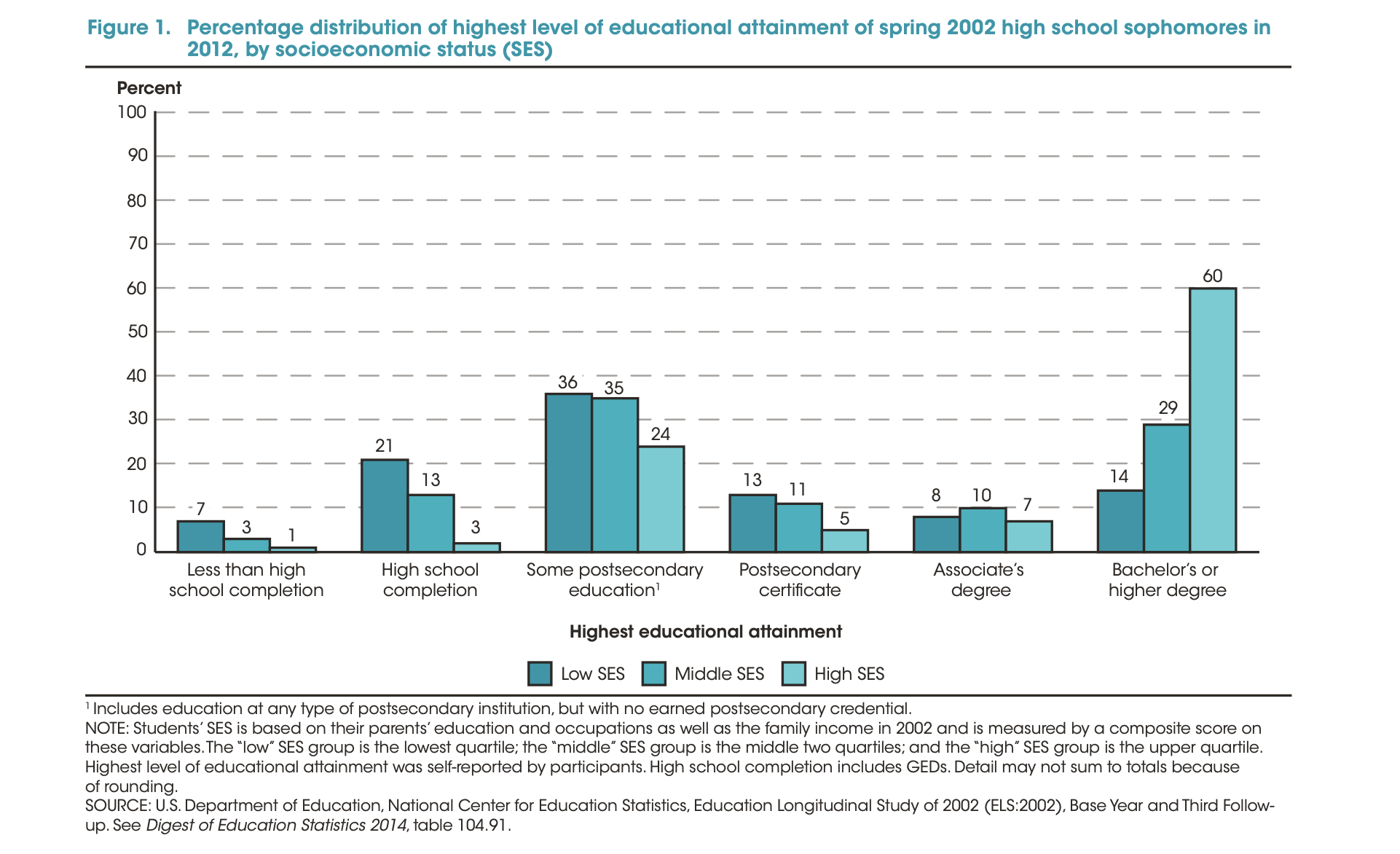

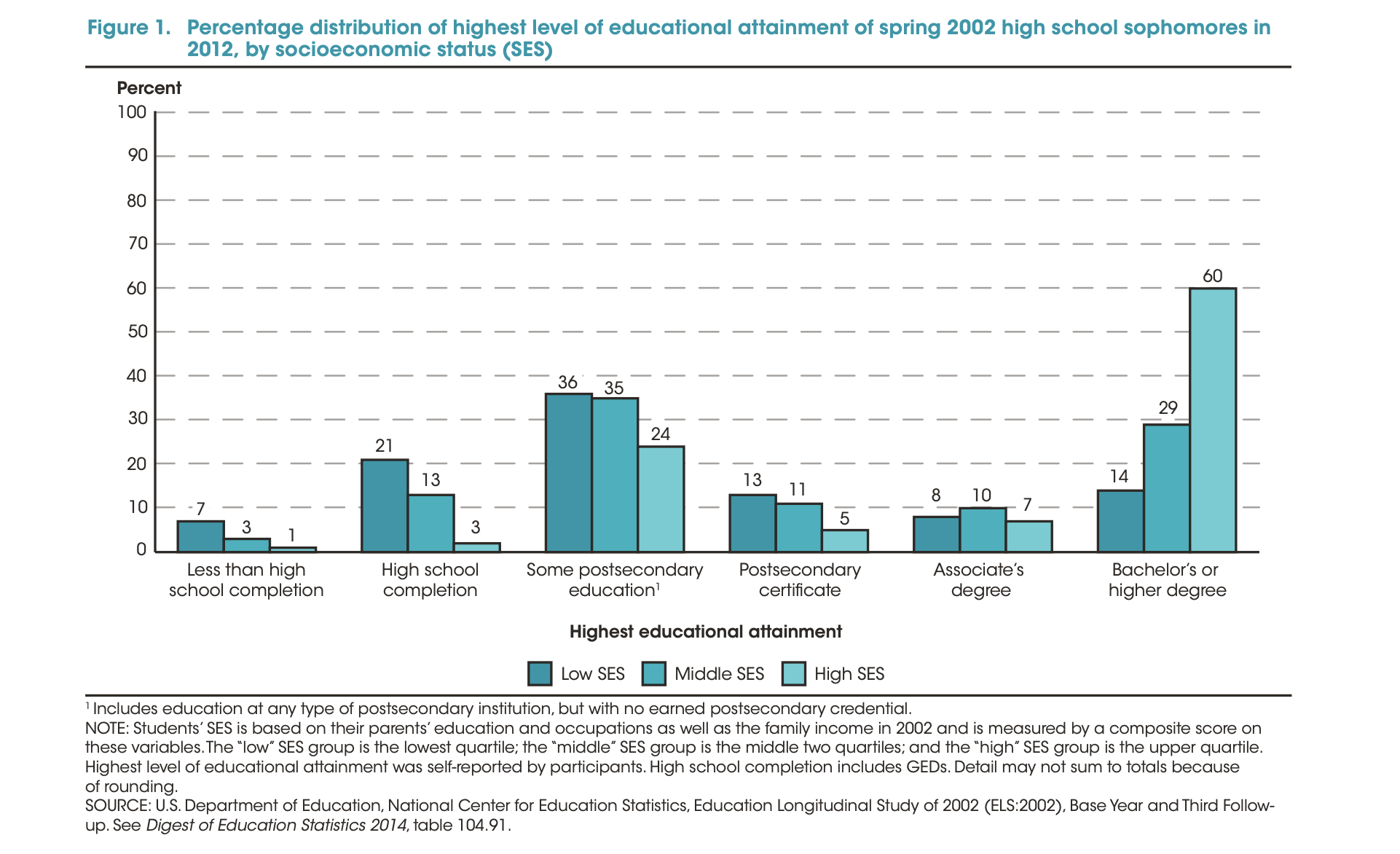

Social Class

Family income, as a measure of social class, makes a much larger difference in educational attainment than it did half a century ago. Data show the effects of family income on educational attainment. Let’s look at how family income affects the likelihood of graduating from high school, attending college, and earning a 4-year degree or higher. The figure below shows that low-income students are more likely to have not completed high school, are far more likely to have only a high school diploma, and are far less likely to have a bachelor's degree or higher than students from middle- and high-income families (National Center for Education Statistics 2015). This income gap in college entry has become larger in recent decades (Bailey & Dynarski 2011).

This chart displays educational attainment of students who were high school sophomores in 2002, measuring outcomes ten years later in 2012. We can see a clear pattern for social class and educational outcomes.

Source: National Center for Education Statistics 2015

Race

Let’s also examine how race affects the likelihood of obtaining a college degree, a benchmark of educational attainment. The racial group with the highest proportion of college graduates is Asian, followed by white, Black, and Latino. College completion rates have been increasing for all of these groups, though the differences persist (Census 2023). The figure below displays this increase, as well as gender differences for each racial category included.

College completion rates have increased overall and for all racial groups; however, women are now earning more college degrees than men for all groups.

Source: Hurst, Pew Research Center 2024

Let’s now look at how race is connected to the likelihood of dropping out of high school, yet another benchmark of educational attainment. In 2022, there were 2.1 million individuals between the ages of 16–24 who had dropped out of high school (National Center for Education Statistics 2024). The figure below shows the percentage of people in that age group who were not enrolled in school and who had not received a high school degree, by race. Though most groups saw a decline in high school dropout rates from 2012 to 2022, some groups did not improve on this measure and racial differences remain.

Though high school dropout rates have declined, racial disparities remain, with American Indian/Alaska Native, Pacific Islander, and Latino youth having the highest rates.

Source: National Center for Education Statistics 2024

Why do some racial groups have lower educational attainment? Four factors are commonly cited:

- The higher poverty rates of their families and lower education of their parents that may leave children ill-prepared for school even before they enter kindergarten.

- The fact that Native American, Black, and Latino families are more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods.

- The underfunded and otherwise inadequate schools that children in these groups often attend.

- Racial discrimination (Ballantine & Hammack 2012; Yeung & Pfeiffer 2009).

Racial discrimination and residence in high-poverty neighborhoods may need additional explanation. At least three forms of racial discrimination impair educational attainment (Mickelson 2003). The first form involves tracking, the sorting of students into different programs according to perceived abilities and intelligence. Students tracked into vocational or general curricula tend to learn less and have lower educational attainment than those tracked into a faster-learning, academic curriculum. Because students of color are more likely to be tracked 'down' rather than 'up,' their school performance and educational attainment suffer.

The second form of racial discrimination involves school discipline. Black and Latino students are more likely than white students to be suspended, expelled, or otherwise disciplined for similar types of misbehavior. Because such discipline again reduces school performance and educational attainment, this form of discrimination helps explain the lower attainment of Black and Latino students.

The third form involves teachers’ expectations of students. As our discussion of the symbolic interactionist perspective on education examined, teachers’ expectations of students affect how much students learn. Research finds that teachers have lower expectations for their Black and Latino students, and that these expectations help to lower how much these students learn.

Turning to residence in high-poverty neighborhoods, it may be apparent that poor neighborhoods have lower educational attainment because they have inadequate schools, but poor neighborhoods matter for reasons beyond their schools’ quality (Kirk & Sampson 2011; Wodtke, Harding, & Elwert 2011). First, because many adults in these neighborhoods have dropped out of high school or are unemployed, children in these neighborhoods lack adult role models for educational attainment. Second, poor neighborhoods tend to be racially segregated. Latino children in these neighborhoods are less likely to speak English 'well' because they lack native English-speaking friends, and Black children are more likely to speak Black English (aka, African American Vernacular English or AAVE) than conventional English, which interferes with school success because teachers hold them to the standard of conventional English.

Additionally, poor neighborhoods have higher rates of violence and crime than wealthier neighborhoods. Children in these neighborhoods thus are more likely to experience high levels of stress, to engage in these behaviors themselves (which reduces their attention and commitment to their schooling), and to be victims of violence (which increases their stress and can impair their neurological development). Crime in these neighborhoods also tends to reduce teacher commitment and parental involvement in their children’s schooling. Finally, poor neighborhoods are more likely to have environmental problems such as air pollution and toxic levels of lead paint, which may lead to asthma and other health problems among children (as well as adults), and impairs the children’s ability to learn and do well in school.

For all these reasons, then, children in poor neighborhoods are at much greater risk for lower educational attainment. As a recent study of this risk concluded, “Sustained exposure to disadvantaged neighborhoods … throughout the entire childhood life course has a devastating impact on the chances of graduating from high school.” If these neighborhoods are not improved, the study continued, “concentrated neighborhood poverty will likely continue to hamper the development of future generations of children” (Wodtke et al. 2011: 731, 733).

Disability

Disability status also impacts educational outcomes. Before proceeding, however, we should clarify disability-related language. Some people prefer to focus on the ability or disability, whereas others focus on the person. Some of them also reclaim the use of language in new ways.

For instance, some people say that they are “people who use wheelchairs” or “people who are neurodiverse.” They use people first language. Person first language is a way to emphasize the person and view the disorder, disease, condition, or disability as only one part of the whole person (NIH 2022). It focuses on the human being first and the difference second. This language developed in the 1970s and 1980s in response to the language of the time. Before person first language, it was common to hear “a victim of epilepsy” or “that poor blind kid,” phrases which denied the humanity of the person experiencing the condition or illness. In this example, the organization People with AIDS focused on the agency of people with AIDS: "We condemn attempts to label us as 'victims,' a term that implies defeat, and we are only occasionally 'patients,' a term that implies passivity, helplessness, and dependence upon the care of others. We are 'People With AIDS'" (The Advisory Committee of People with AIDS 1983).

Some people will say that they are d/Deaf (some capitalize the term to denote an identity), autistic, or neurodivergent. This is an example of identity first language. Identity first language focuses on an inherent part of someone’s identity, such as deafness or neurodiversity. It is a response to person first language (Brown 2012). Lydia Brown, an Autistic activist, writes: "In the autism community, many self-advocates and their allies prefer terminology such as 'Autistic,' 'Autistic person,' or Autistic individual' because we understand autism as an inherent part of an individual’s identity" (Brown 2011).

Similarly, d/Deaf people often use identity first language to emphasize that being deaf isn’t just a physical condition that indicates a lack of hearing. d/Deaf is also a community and culture with its own language and social norms.

Another group of activists is using the word 'crip,' derived from the word 'cripple,' to describe themselves. They fiercely reclaim this word to describe the physical challenges they experience: "Like queer, crip(ple) is a slur that has been reclaimed by many physically disabled people, especially those who also identify as queer. There are a lot of reasons that people identify as crip(ple)s, but like queer, one reason is to have a word that is yours… It is based in the radical idea that disabled people can be openly disabled and still be deserving of respect" (Strauss 2018). Crips claim that name as a source of their power.

Getting back to the data, disability impacts educational outcomes. For instance, d/Deaf students have lower levels of educational achievement than hearing students. The table below considers disability and race, addressing the overall educational attainment for Black Deaf, Black Hearing, White Deaf, and White Hearing students. We see that hearing people have higher educational attainments than d/Deaf people overall. However, for the PhD, JD, and MD levels, Black hearing and white d/Deaf people comprise only 0.7% of each population attained that level of education. Black d/Deaf people had the lowest level of educational achievement of any category.

This figure displays educational attainment for Black d/Deaf, Black hearing, white d/Deaf, and white hearing students. White hearing students have the highest educational attainment in all categories. Black d/Deaf students have the lowest educational attainment.

“Overall Educational Attainment” from Postsecondary Achievement of Black Deaf People in the United States (p.12) by Carrie Lou Garberoglio, Lissa D. Stapleton, Jeffrey Levi Palmer, Laurene Simms, Stephanie Cawthon, and Adam Sale, National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes, is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Dr. Stapleton and her colleagues explore why college graduation rates for d/Deaf women of color are particularly low. As of 2017, Only 13.7% of d/Deaf Black women get a bachelor’s degree. In comparison, 26.5% of Black hearing women graduate college (Garberoglio et al 2019). You may recall that many social problems are intersectional – people experience them differently based on their various social locations. In this case, Dr. Stapleton looks at how gender, race, and disability intersect to understand these students’ unique experiences. She explains that part of the difficulty for these students is related to being able to be d/Deaf, a woman, and a person of color.

Audism is one factor in explaining the suffering in these students’ stories and the different outcomes of d/Deaf students. Audism is “the notion that one is superior based on one’s ability to hear or behave in a manner of one who hears” (Humphries 1977:12). Students who are d/Deaf experience discrimination because others assume hearing people are superior. They design the experience of education with hearing people in mind. Audism is one specific form of ableism, the systemic, institutionalized oppression of disabled people. Another factor in the experience of these students is racism. As we see in the stories of the d/Deaf students, people who disabled and of color can experience prejudice based on the constellation of their social locations – the intersection of ableism and racism.

Dr. Stapleton (2015) shares stories and quotes about and from students she interviewed as part of her qualitative research. In the following quote, she describes the experience of a d/Deaf Asian student:

"I have had several one-on-one interactions with Amy over her two years at the institution. She struggled with shifting identities between her life at home and school. At home, her family treated her like a hearing person; she spoke her ethnic language, participated in all her ethnic cultural practices, and used hearing aids. When she came to school, she only signed and did not interact with other Asian students, as most of the d/Deaf students on campus were White. She did not feel hearing, Asian, or d/Deaf enough to fit into the residential or campus community. She struggled. Because of cultural taboos, she was afraid to tell her parents that she needed counseling and was unable to find a counselor to meet her communication needs (simultaneously signing and speaking), so she started to shut down. ... The lack of congruency and peace she felt affected her schoolwork, her friendship circles, and now her ability to stay at school because her behavior had become unpredictable and distant."

The remaining quotes are directly from d/Deaf students themselves:

"Society assumes and exerts superiority over their capabilities of hearings. In Deaf schools, deaf youths are [likely] to experience being discriminated against based on their deafness because the culture is too deep-rooted with the belief that deaf people can do what hearing people do, only that they can’t hear."

"In mainstream schools, I know this because I experienced this more than often. Sometimes I have teachers or interpreters who think I need some assistance with what to say. They think they know our needs. Sometimes we will have someone jump in to 'help' us communicate. It is very embarrassing when speaking to a hearing student, especially if we are attracted to them and always have interpreters jump in act like we need their help to talk."

"Hearing people misunderstood our facial, body and gesture expressions and avoided us; even told us to 'dial down.'"

Disability can impact educational outcomes in other ways. For instance, people experience different and overlapping learning differences as part of being neurodivergent. Researcher David Pollack provides a model of neurodivergence in the figure below.

Neurodiversity is complicated. Often neurodiversity brings particular strengths and challenges. Why do you think that this model focuses on strengths rather than challenges?

“Neurodiversity is complicated” © Genius Within CIC, Dr Nancy Doyle, based on the highly original work of Mary Colley; all rights reserved and included with permission

In education, disability is often framed in terms of a deficit model: That disabled students are lacking in skills or abilities to succeed. In contrast, the model above focuses on strengths of neurodivergent people. We see similar tensions in how people understand and explain disabilities such as neurodiversity. On one hand, we have a medical model of disability, based on individual pathology or abnormality (Walker and Raymaker 2021). In this model, differences in reading, calculating, writing, or interacting with others is considered a problem, something to be treated or cured.

In the 1990s, adults with these labels began to push back against these categorizations. Their claim was that these conditions should be considered normal human neurology variants. Patient-centered care advocate Valerie Billingham (1998) coined the phrase, “Nothing about me, without me.” She was talking about the need to include the patient at the center of decision-making around patient health and treatment choices. This phrase is used widely today by autism awareness activists, who have expanded the meaning to include the idea that people who are neurodivergent should be the ones describing their own experiences. The letter in the figure below provides one example of this. People with autism are the ones who should make choices about what they need in order to fully participate in school and in life. They should propose the laws, policies, and practices that make their participation possible.

This sticky note describes one positive experience of neurodiversity. How does the phrase, “I Like Being Autistic” challenge your ideas about neurodiversity?

“Photo” by walkinred is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

In response to the medical model that pathologizes disability, advocates and social scientists have described a social model of disability. Some experts see neurodiversity itself is a civil rights challenge. They argue that society privileges people who are considered neurotypical. Not only are neurodiverse people stigmatized with a label that implies disease, symptom, or medical problem, but social institutions themselves are unequal. They propose that we strive for "neuro-equality (understood to require equal opportunities, treatment and regard for those who are neurologically different)" (Fenton and Krahn 2007: 1). Likewise, Nick Walker (2001), a queer, transgender, and autistic scholar, encourages us to see beyond the medical model. She writes,

"The neurodiversity paradigm starts from the understanding that neurodiversity is an axis of human diversity, like ethnic diversity or diversity of gender and sexual orientation, and is subject to the same sorts of social dynamics as those other forms of diversity – including the dynamics of social power inequalities, privilege, and oppression."

Reframing Achievement Gaps

Gloria Lasdon-Billings (pictured below) is an educator and an educational researcher. As the president of American Educational Research Association (AERA), she gave the presidential address in 2006. She examines the 'achievement gap' and explores what makes the most effective teacher, particularly those teachers who can close the achievement gap for Black students. If you would like to learn more about her, read this article: Gloria Ladson-Billings: Daring to Dream in Public.

In her 2006 presidential address, Ladson-Billings argues that sociologists should study 'educational debt' rather than the 'achievement gap.' Educational debt is the cumulative impact of fewer resources and other harm directed at students of color, including economic, sociopolitical, and moral characteristics.

Economically, educational debt consists of unequal spending in education over centuries. Segregation supported economic inequality in education. Today, because schools are funded based on population and property tax revenues, schools in rich neighborhoods, which are more likely to be white, spend more on each individual child’s education.

Sociopolitically, we see the exclusion of Black and Brown people from voting. They are also excluded from decision-making in school districts, state houses, and the federal government. For example, in 2018, 78% of school board members were white, even though 50% of all public school students are of color (Bland 2022; National School Boards Association 2018). Families of color are excluded from power in education.

Morally, Ladson-Billings writes, "A moral debt reflects the disparity between what we know and what we actually do" (Ladson-Billings 2006:8). She further asks:

"What is it that we might owe to citizens who historically have been excluded from social benefits and opportunities? Randall Robinson (2000) states: No nation can enslave a race of people for hundreds of years, set them free bedraggled and penniless, pit them, without assistance in a hostile environment, against privileged victimizers, and then reasonably expect the gap between the heirs of the two groups to narrow. Lines begun parallel and left alone, can never touch" (Ladson-Billings 2006: 8).

In the end, she argues that the achievement gap is a result of educational debt. Further, educational debt is caused by the wider social forces of systemic racism, poverty, and health inequities. If you want to learn more about the experience of educational debt, please watch How America’s Public Schools Keep Kids in Poverty.

The Impact of Education

Have you ever applied for a job that required a high school degree? Are you going to college in part because you realize you will need a college degree for a higher-paying job? As these questions imply, the US is a credential society (Collins 1979). This means at least two things. First, a high school diploma or college degree (or beyond) indicates that a person has acquired the needed knowledge and skills for various jobs. Second, a degree at some level is a requirement for most jobs. As you know, a college degree today is a virtual requirement for many decent-paying jobs. The ante has been upped considerably over the years: In earlier generations, a high school degree (if that) was all that was needed, if only because so few people graduated from high school to begin with. With so many people graduating from high school today, a high school degree is not worth as much on the job market. Today’s society increasingly requires skills and knowledge that only a college education brings.

On the average, college graduates have much higher annual earnings than high school graduates. How much does this outcome affect why you decided to go to college?

© Thinkstock

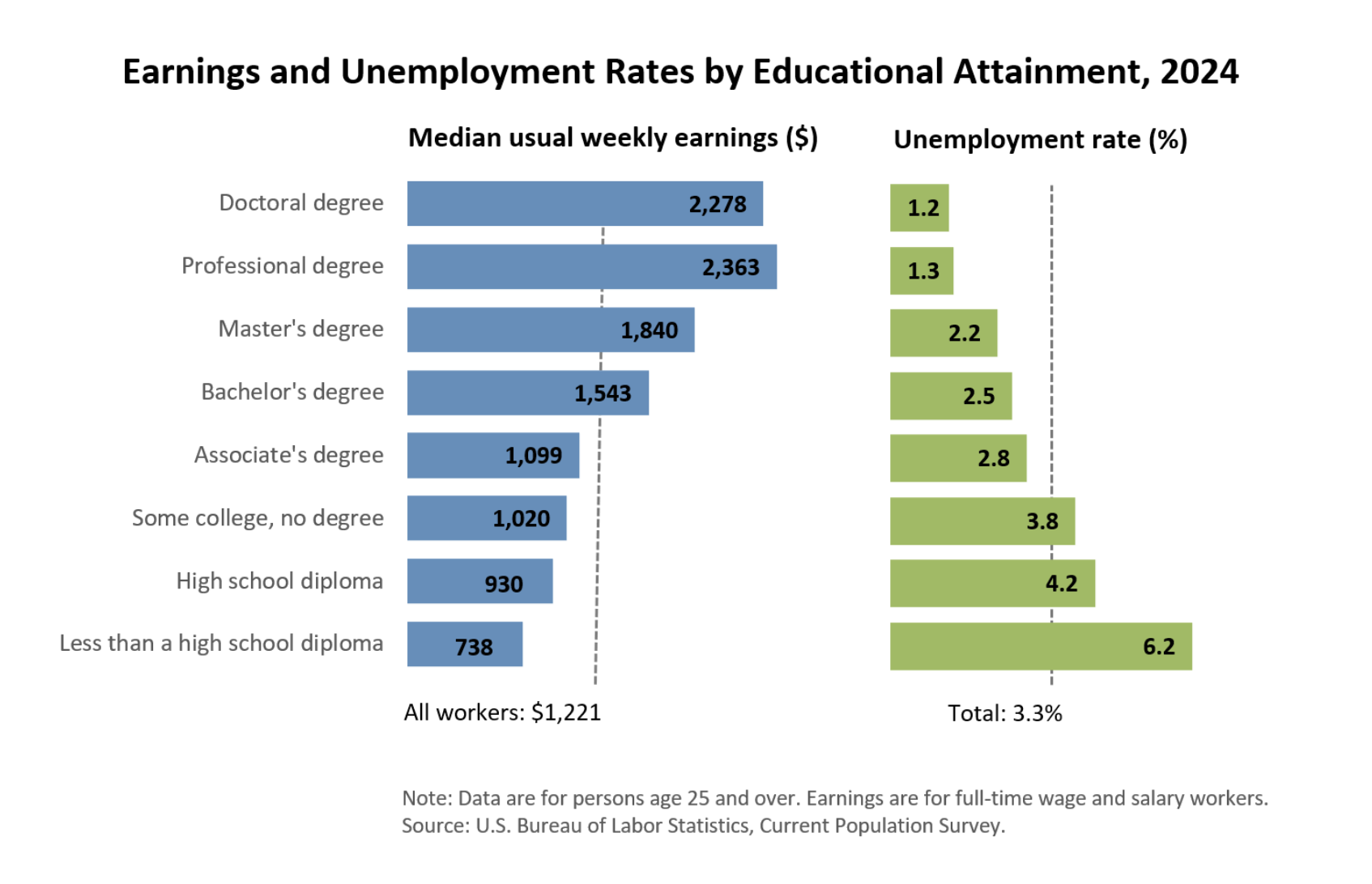

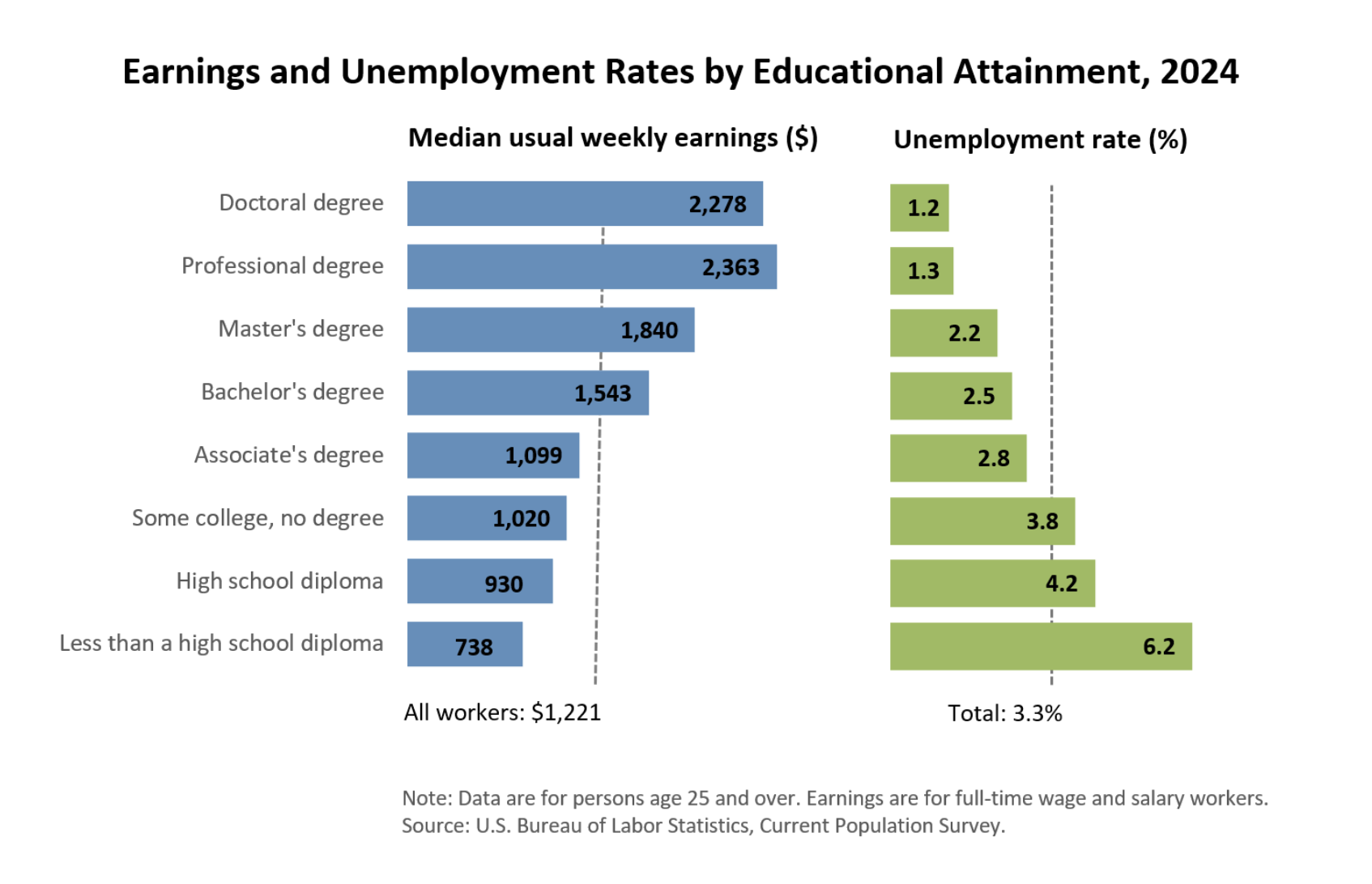

A credential society also means that people with more formal education achieve higher incomes. Annual earnings are indeed much higher for people with more education, as the figure below illustrates. Individuals aged 25 and older with a bachelor's degree earned $1,543 per week on average in 2024, whereas those with a high school diploma earned only $930 per week. Considering the extremes, those with a professional or doctoral degree earned far more than $2,000 weekly, whereas those with no high school diploma earned only $738 weekly (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2025). Gender and race affect the payoff we get from our education, but education itself still makes a huge difference for our incomes.

This chart show the average (median) weekly earnings for workers 25 years of age or older by educational attainment. It also shows unemployment rates by educational attainment. There are large differences in earnings between those with a bachelor's degree or higher and those without, and in unemployment between those with an Associate's degree or higher and those without.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics 2025

Education affects other outcomes beyond income, such as health outcomes. For instance, education may impact the age people tend to die. Simply put, people with higher levels of education tend to die later in life, and those with lower levels tend to die earlier (Miech, Pampel, Kim, & Rogers 2011). The reasons for this disparity are complex, but two reasons stand out. First, more highly educated people are less likely to smoke and engage in other unhealthy activities, and they are more likely to exercise and to engage in other healthy activities and to eat healthy diets. Second, they have better access to high-quality health care. Thus, education (as well as other measures of social class) is protective of our health.