We have already discussed several examples of achievement gaps for various measures of educational attainment. Here will will focus primarily on other issues regarding grade school (elementary and secondary education). We include both historical and contemporary problems, as historical social problems continue to impact individuals and communities today.

Educational Inequality

The elementary (K–8) and secondary (9–12) education system today faces many issues of interest not just to educators and families but also to sociologists and other social scientists. We cannot discuss all these issues here, but we will highlight several.

Earlier we mentioned that schools differ greatly in their funding, their conditions, and other aspects. Noted author and education critic Jonathan Kozol refers to these differences as “savage inequalities,” to quote the title of one of his books (Kozol 1991). Kozol’s concern over inequality in schools stemmed from his experience as a young teacher in a public elementary school in a Boston inner-city neighborhood in the 1960s. Kozol was shocked to see that his school was literally falling apart. The building itself was decrepit, with plaster falling off the walls and bathrooms and other facilities substandard. Classes were large, and the school was so overcrowded that Kozol’s fourth-grade class had to meet in an auditorium, which it shared with another class, the school choir, and for a time, a group of students practicing for the Christmas play. Kozol’s observations led to the writing of his first award-winning book, Death at an Early Age (Kozol 1967).

Kozol (1991) later traveled around the United States and systematically compared public schools in several cities’ inner-city neighborhoods to those in the cities’ suburbs. Everywhere he went, he found great discrepancies in school spending and in the quality of instruction. In schools in Camden, New Jersey, for example, spending per pupil was less than half the amount spent in the nearby, much wealthier town of Princeton. Chicago and New York City schools spent only about half the amount that some of the schools in nearby suburbs spent.

These numbers were reflected in other differences Kozol found when he visited city and suburban schools. In East St. Louis, Illinois, where most of the residents were poor and almost all were Black, schools had to shut down once because of sewage backups. The high school’s science labs were 30-50 years out of date when Kozol visited them. The biology lab had no dissecting kits. A history teacher had 110 students but only 26 textbooks, some of which were missing their first one hundred pages. At one of the city’s junior high schools, many window frames lacked any glass, and the hallways were dark because light bulbs were missing or not working. Visitors could smell urinals one hundred feet from the bathroom.

Contrast these conditions with those Kozol observed in suburban schools. A high school in a Chicago suburb had seven gyms and an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Students there could take classes in seven foreign languages. A suburban New Jersey high school offered fourteen AP courses, fencing, golf, ice hockey, and lacrosse, and the school district there had ten music teachers and an extensive music program.

Jonathan Kozol has written movingly of “savage inequalities” in American schools arising from large differences in their funding and in the condition of their physical facilities.

Thomas Hawk – El Paso High School – CC BY-NC 2.0; Nitram242 – Detroit School – CC BY 2.0

From his observations, Kozol concluded that the US is shortchanging its children in poor rural and urban areas. Children from low-income families start out in life with many strikes against them. The schools they attend compound their problems and help ensure that the American ideal of equal opportunity for all remains just that – an ideal – rather than a reality. As Kozol (1991: 233) observed,

“All our children ought to be allowed a stake in the enormous richness of America. Whether they were born to poor white Appalachians or to wealthy Texans, to poor black people in the Bronx or to rich people in Manhasset or Winnetka, they are all quite wonderful and innocent when they are small. We soil them needlessly.”

Although the book in which Kozol reported these conditions was published a few decades ago, ample evidence shows these conditions persist today. One news report discussed public schools in Washington, DC: More than 75% of the schools in the city had a leaking roof at the time the report was published, and 87% had electrical problems, some of which involved shocks or sparks. Most of the schools’ cafeterias (85%) had health violations, including peeling paint near food and rodent and roach infestation. Thousands of requests for building repairs, including 1,100 labeled “urgent” or “dangerous,” had been waiting more than a year to be addressed. More than one-third of the schools had a mouse infestation, and in one elementary school, there were so many mice that the students gave them names and drew their pictures. An official with the city’s school system said, “I don’t know if anybody knows the magnitude of problems at D.C. public schools. It’s mind-boggling” (Keating & Haynes 2007).

Large funding differences in the nation’s schools also endure. In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for example, annual per-pupil expenditure was $10,878 in 2010, whereas in nearby suburban Lower Merion Township it was $21,110, or 95% higher than Philadelphia’s expenditure (Federal Education Budget Project 2012).

Teacher salaries are related to these funding differences. Salaries in urban schools in low-income neighborhoods are markedly lower than those in schools in wealthier neighborhoods (Dillon 2011). As a result, teachers at the low-income schools tend to be less experienced teachers just out of college or are burdened with large classes and few resources. Thus, they are less likely than their counterparts at wealthier schools to be effective teachers, in part due to structural issues. In fact, teachers are underpaid in general given their higher levels of education than most workers, and teacher pay overall declined in the 2010s, according to the US Census (see below).

In this graphic from the US Census that uses data from the 2010 to 2019 American Community Survey, we see that pay for high school, elementary and middle school, and special education teachers declined from 2010 to 2019, though some began to rebound. See an interactive visualization of teacher pay on this Census site.

Source: US Census 2024

School Segregation

A related issue to school inequality is school racial segregation. To make informed decisions, people need the ability to read and write. A literate populace was fundamental to establishing a strong democracy. Access to education expanded in 1800s; however, despite this intention, we haven’t yet achieved universal access to education, which is people’s equal ability to participate in an education system.

Early education systems in the US were segregated. Segregation refers to the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions. Schools were segregated by gender, race, ability/disability, and class. Educator and researcher Gloria Ladson-Billings (2006: 5) summarizes the history of segregation in education in the US:

"In the case of African Americans, education was initially forbidden during the period of enslavement. After emancipation, we saw the development of freedmen’s schools whose purpose was the maintenance of the servant class. During the long period of legal apartheid, African Americans attended schools where they received cast off textbooks and materials from White school... Black students in the south did not receive universal secondary education until 1968."

As discussed later in this chapter, US federal government policies required that Indigenous children stay in residential schools just for them. Additionally, d/Deaf students, when they could access education, received that education in segregated facilities, usually in state boarding schools. In these schools, students were often taught to lip read and speak, preparing them only to interact in a hearing world rather than also respecting d/Deaf culture. Additionally, Mexican and other Spanish-speaking children experienced segregation. In Texas and California, 80% of the school districts were legally segregated (Arce 2021). Other states practiced informal segregation that was no less harmful.

Even when education was legal for many marginalized groups, it was provided in separate, segregated facilities that often (but not always) provided lower-quality education. This history of inequality is the deep roots of unequal educational outcomes.

Focusing more specifically on race, schools in the South were racially segregated by law before 1954, practice referred to as de jure segregation – segregation 'by law.' Communities and states had laws that dictated which schools white children attended and which schools Black children attended. Schools were either all white or all Black, and, inevitably, white schools were much better funded than Black schools.

The educational goal for many families was to end legal segregation. For example, in 1931, a Californian Hispanic family sued that school district because students were segregated based on having Hispanic-sounding last names. This was the first case where educational segregation was declared illegal in a federal court (Arce 2021). Segregation became more widely illegal in the United States with the US Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. The Brown decision declared that separating children based on race in school was illegal. This change in federal law launched passionate and often violent conflicts to integrate schools. Southern school districts fought this decision with violence and legal machinations, and de jure school segregation did not really end in the South until the civil rights movement won its major victories a decade later. In addition to the stories you may already know, desegregation also occurred with Latinx students. If you’d like to learn more, feel free to watch this video, Austin Revealed: Chicano Civil Rights “Desegregation & Education”, in which students talk about their experiences with segregation and desegregation.

Meanwhile, northern schools were also segregated, and decades after the Brown decision, they became even more segregated. School segregation in the North stemmed, both then and now, not from the law but from neighborhood residential patterns – recall the concept of racial residential segregation that we discussed in the chapter on Neighborhoods and Housing. Because children usually go to schools near their homes, if adjacent neighborhoods are all white or all Black, then the schools for these neighborhoods will also be all white or all Black, or mostly so. This type of segregation is called de facto segregation – segregation 'by fact' rather than by law. In other words, one reason for this segregation is that we tend to live in neighborhoods that are also segregated. Rich people, who are more often white, tend to live with other rich people. Because children commonly attend schools in their own neighborhoods, the schools mirror the lack of integration in neighborhood communities. However, recall that residential segregation is in part due to a history of redlining, which was a state-sanctioned form of racial discrimination.

Many children today attend schools that are racially segregated because of racial residential segregation.

© Thinkstock

Since 1954, many laws that move from segregated to integrated education have been passed. In 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act which prohibited discrimination based on race, color, ethnicity, and national origin. Title IV of this act prohibits segregation in schools. Title VI of this act prohibits discrimination based on race, color, ethnicity, and national origin for any programs that receive federal funds, including schools and colleges. The educators at Learning for Justice describe Title VI as “one of the biggest victories of the civil rights movement” (Collins 2019). These legal changes resulted from fierce activism by Black, Brown, and white people. You can see leaders, activists, and a button from the related Freedom March in the emphasis box below. Also, you have the option of exploring Learning for Justice more if you wish.

In separate legislation, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 stated, "No person in the United States shall, based on sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance" (United States Congress 1972).

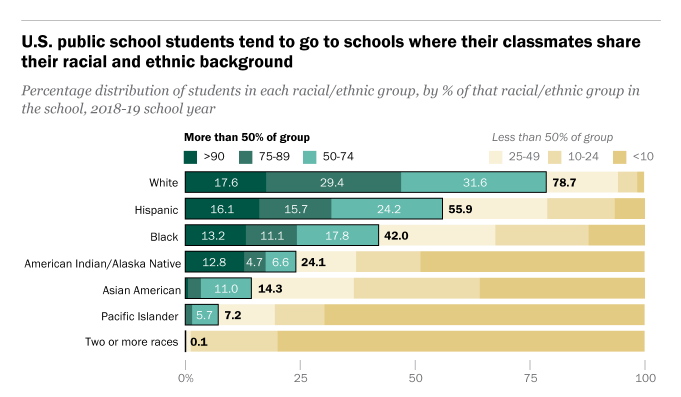

Educational segregation is illegal today, but many schools and school districts are de facto segregated. In a recent analysis of US Department of Education data, Pew Research reports that most students attend schools that serve other students of their race and ethnicity (see the figure below). In other words, white students are likely to attend schools where half or more of the other students are also white. Hispanic students are also likely to attend schools where at least half of the other students are Hispanic. For other racial groups, the proportions are slightly smaller, partially because the numbers of people who make up those groups are smaller as well.

During the 1960s and 1970s, states, municipalities, and federal courts tried to reduce de facto segregation by busing urban Black children to suburban white schools and, less often, by busing white suburban children to Black urban schools. Busing inflamed passions as perhaps few other issues did during those decades (Lukas 1985). White parents opposed it because they did not want their children bused to urban schools, where, they feared, the children would be unsafe and receive an inferior education. The racial prejudice that many white parents shared heightened their concerns over these issues. Black parents were more likely to see the need for busing, but they too wondered about its merits, especially because it was their children who were bused most often and faced racial hostility when they entered formerly all-white schools.

As one possible solution to reduce school segregation, some cities have established magnet schools, schools for high-achieving students of all races to which the students and their families apply for admission (Vopat 2011). Although these schools do help some students whose families are poor and of color, their impact on school segregation has been minimal because the number of magnet schools is low and because they are open only to the very best students who, by definition, are also few in number. Some critics also say that magnet schools siphon needed resources from public school systems and that their reliance on standardized tests makes it difficult for Black and Latinx students to gain admission.

In addition to prohibiting segregation based on race, ethnicity, color, and gender, federal law requires that students labeled as disabled receive equitable education and educational support. Discrimination against differently-abled people became illegal with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. To ensure equitable education, schools began to integrate classrooms. This practice, known as inclusion, moves disabled students from residential schools and separate classrooms into inclusive classrooms. Inclusion is also commonly called mainstreaming, a unique type of integration.

In one example of inclusion supported by law, the Education of All Handicapped Children Act (EHC) of 1975 included deafness as one of the categories under which children with disabilities may be eligible for special education and related services. This law required public schools to provide educational services to disabled children ages three to twenty one. This law included d/Deaf students as disabled under the law, expanding the services available to them and increasing integration.

Indian Boarding Schools

In discussing school segregation and broader inequalities within the institution of education, we must describe the ongoing impact of Indian boarding schools on Indigenous communities across North America.

Colonizers saw the very existence of Indigenous people as a problem because the Indigenous people inhabited land that the colonizers wanted. They established mandatory residential boarding schools for Indigenous children, a part of a strategy of genocide. Genocide is the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group. Many Indigenous children died in residential schools (National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition N.d.). The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report, released in May 2022, documents the recent findings that at least 500 children were buried in 53 burial sites on residential school properties (Newland 2022). Researchers expect to find even more burials. Recent discoveries in Canada indicate that up to 6,000 First Nations (the preferred term) children died in Canadian residential boarding schools (AP News 2021). You can read the full Investigative Report if you wish.

The federal report details some of the basic facts. The US established 408 federal boarding schools between 1891 and 1969. Congress established laws that required Indigenous parents to send their children to these boarding schools. Government records document, “[i]f it be admitted that education affords the true solution to the Indian problem, then it must be admitted that the boarding school is the very key to the situation” (Newland 2022:38).

Colonists attempted to erase Indigenous people and cultures by requiring students to learn English and agriculture, and punishing the children, sometimes with beatings, if they spoke their Indigenous languages or practiced their own religious and spiritual practices. However, Indigenous people survived, reclaimed their cultures, and revived their practices over time. We will return to this historical problem in the chapter on Conflict, War, and Terrorism, including a discussion of how Indian boarding schools were part of the process of genocide in North America.

If you would like to learn more about residential schools from those who experienced them, you could watch How the US Stole Thousands of Native American Children.

Personal Profile

Deb Haaland (pictured below), US Secretary of the Interior in the Biden Administration, discussed her family's experience with Indian boarding schools:

"My great grandfather was taken to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. Its founder coined the phrase 'kill the Indian, and save the man,' which genuinely reflects the influences that framed the policies at that time.”

She describes the history of Indian boarding schools in the following way:

"Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act of 1819, the United States enacted laws and implemented policies establishing and supporting Indian boarding schools across the nation. The purpose of Indian boarding schools was to culturally assimilate indigenous children by forcibly relocating them from their families and communities to distant residential facilities where their American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian identities, languages and beliefs were to be forcibly suppressed. For over 150 years, hundreds of thousands of indigenous children were taken from their communities" (Haaland 2021).

Deb Haaland was the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary. She is a registered member of the Laguna Puebla tribe.

“Deb Haaland” by the U.S. House Office of Photography is in the Public Domain

However, genocide, loss and suffering is not the whole story. Indigenous people use education to heal generational harm. We can see this healing power in efforts to restore and strengthen Indigenous languages. In the following quote, Indigenous biologist, activist, and citizen of the Potawatomi Nation, Robin Wall Kimmerer, links language, culture, and healing, writing that as language is restored, wholeness is also restored:

"And so it has come to pass that all over Indian Country there is movement for revitalization of language and culture growing from the dedicated work of individuals who have the courage to breathe life into ceremonies, gather speakers to reteach the language, plant old seed varieties, restore native landscapes, bring the youth back to the land. The people of the Seventh Fire walk among us. They are using the fire stick of the original teachings to restore health to the people, to help them bloom again and bear fruit" (2013: 368).

This revitalization of language and culture demonstrates the resistance and resilience of Indigenous people. It also reclaims the power of education to support educational equity and justice:

"Dorothy Lazore, a teacher of immersion Mohawk at Akwesasne, describing a basic paradigm shift in how Indigenous children view schooling: ‘For Native people, after so much pain and tragedy connected with their experience of school, we finally now see Native children, their teachers and their families, happy and engaged in the joy of learning and growing and being themselves in the immersion setting'" (Johansen 2004: 569).

The genocide of people and culture that occurred when colonists established Indian residential schools created wounds that remain unhealed today. At the same time, Indigenous people are reclaiming the bones of their children, their languages and ceremonies, and even sometimes the schools themselves in order to create a more just world.

The Debate Over School Choice

Children who attend a public school ordinarily attend the school that is designated for the neighborhood in which they live, and they and their parents normally have little choice in the matter. One of the most popular but also controversial components of the school reform movement today is school choice, in which parents and their children, primarily from low-income families in urban areas, receive public funds to attend a school different from their neighborhood’s school.

School choice has two components. The first component involves education vouchers, which parents can use as tuition at private or parochial (religious) schools. The second component involves charter schools, which are public schools (because public funds pay for students’ tuition) built and operated by for-profit companies. Students normally apply for admission to these schools. Sometimes they are accepted based on their merit and potential, and sometimes they are accepted by lottery. Both components have strong advocates and fierce critics.

Advocates of school choice programs involving education vouchers say they give low-income families an option for high-quality education they otherwise would be unable to afford. These programs, the advocates add, also help improve the public schools by forcing them to compete for students with their private and parochial counterparts. In order to keep a large number of parents from using vouchers to send their children to the latter schools, public schools have to upgrade their facilities, improve their instruction, and undertake other steps to make their brand of education an attractive alternative. In this way, school choice advocates argue, vouchers have a “competitive impact” that forces public schools to make themselves more attractive to prospective students (National Conference of State Legislatures 2011).

Critics of school choice programs say they harm the public schools by decreasing their enrollments and therefore their funding. Public schools do not have the money now to compete with private and parochial ones, nor will they have the money to compete with them if vouchers become more widespread. Critics also worry that voucher programs will lead to a “brain drain” of the most academically motivated children and families from low-income schools (Crone 2011).

Some studies find small improvements with school choice policies, but methodological problems make conclusions difficult (DeLuca & Dayton 2009). Other research has found a negative impact. For instance, school choice has been found to deepen racial educational disparities rather than to improve them (French 2025). In a review of four studies, The Brookings Institute reports that private school choice programs do not improve test scores, but rather lower them:

"Four recent studies, four different programs, different research approaches, but the same general finding—using vouchers to attend private schools leads to lower math scores and, in one study, lower reading scores too. ... If the four studies suggest anything, it’s that private schools have no secret key that unlocks educational potential." (Dynarski & Nichols 2017).

In the book The Choice We Face: How Segregation, Race, and Power Have Shaped America's Most Controversial Education Reform Movement, Jon Hale (2021) links school choice and voucher programs to educational inequalities as well as to the privatization of schooling, which was founded on racist and elitist ideas.

Moreover, in Milwaukee, enrollment decline from the use of vouchers cost the school system $26 million in state aid during the 1990s, forcing a rise in property taxes to replace the lost funds. Because the students who left the Milwaukee school system came from most of its 157 public schools, only a few left any one school, diluting the voucher system’s competitive impact. Thus although school choice programs may give some families alternatives to public schools, they might not have the competitive impact on public schools that their advocates claim, and they may cost public school systems state aid (Cooper 1999).

About 5,000 charter schools operate across the nation, with about 3% of US children attending them. Charter schools and their proponents claim that students fare better in these schools than in conventional public schools because of the charter schools’ rigorous teaching methods, strong expectations for good behavior, small classrooms, and other advantages (National Alliance for Public Charter Schools 2012).

Critics say charter schools incur the same problems that education vouchers incur: They take some of the brightest students from a city’s conventional public schools and lead to lower funding for these schools (Ravitch 2010; Rosenfeld 2012). Critics also cite research findings that charter schools do not in fact deliver the strong academic performance claimed by their advocates. For example, a study that compared test scores at charter schools in sixteen states with those at public schools found that the charter schools did worse overall: 17% of charter schools had better scores than public schools, 46% had scores similar to those of public schools, and 37% had lower scores (Center for Research on Education Outcomes 2009).

Even when charter school test scores are higher, there is the methodological problem that students are not randomly assigned to attend a charter school (Basile 2010). It is thus possible that the students and parents who apply to charter schools are more highly motivated than those who do not. If so, the higher test scores found in some charter schools may reflect the motivation of the students attending these schools, and not necessarily the schools’ teaching methods. It is also true that charter schools do not usually enroll students who know little English (whose parents are immigrants) and students with disabilities who also face obstacles in education. This is yet another possible reason that a small number of charter schools outperform public schools.

Though the research is somewhat mixed, there is evidence that school choice perpetuates educational inequalities, thus being a problem of education itself.

Caution

We discuss school bullying and violence next.

School Bullying and Violence

Bullying is another social problem in the nation’s elementary and secondary schools and is often considered a specific type of school violence. However, bullying can take many forms, such as taunting, that do not involve the use or threat of physical violence. As such, we consider bullying here as a separate problem while acknowledging its close relation to school violence.

Bullying has been defined as, “physical and verbal attacks and harassment directed at a victim(s) by one student or a group of students over an extensive period of time” (Moon, Hwang, & McCluskey 2011). Another definition is also helpful: “The use of one’s strength or popularity to injure, threaten or embarrass another person on purpose” (St. George 2011). As these definitions suggest, bullying can be physical in nature (violence such as shoving and punching), verbal (teasing, taunting, and name calling), and social (spreading rumors, breaking up friendships, deliberately excluding someone from an activity). An additional form of bullying that has emerged in the last decade or so is cyberbullying, which involves the use of the Internet or digital technologies to bully others (e.g., rumors can be spread via Facebook).

Bullying is a serious problem for at multiple reasons. First, bullying is a common occurrence. Between one-fifth and one-third of students report being victimized by some form of bullying during the school year (National Center for Education Statistics 2025b; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control 2010). Second, bullying can have serious consequences (Adams & Lawrence 2011). Students who are bullied often experience psychological problems that can last into adulthood. These problems include anxiety, depression, loneliness, sleeplessness, and suicidal thoughts. Their school performance (grades, attendance, and participation in school activities) may also decline. Since bullying now occurs in online spaces that are less monitored by adults but frequented by teens, cyberbullying has become a concern among adolescents. In 2011, Jamey Rodemeyer died by suicide after being bullied by classmates on social media because he was gay. A week before he died, Jamey wrote on his site, “I always say how bullied I am, but no one listens. What do I have to do so people will listen to me?” (Tan 2011). In addition, bullying victims sometimes respond by lashing out in violence – many of the mass school shootings of the 1990s were committed by boys who had been bullied.

The issue of school violence was a frequent headline during the 1990s, when many children, teachers, and other individuals died in the nation’s schools. From 1992 until 1999, 248 students, teachers, and other people died from violent acts (including suicide) on school property, during travel to and from school, or at a school-related event, for an average of about thirty-five violent deaths per year (Zuckoff 1999).

Several of these deaths occurred in mass shootings. In just a few examples, in December 1997, a student in a Kentucky high school shot and killed three students in a before-school prayer group. In March 1998, two middle school students in Arkansas pulled a fire alarm to evacuate their school and then shot and killed four students and one teacher as they emerged. Two months later, an Oregon high school student killed his parents and then went to his school cafeteria, where he killed two students and wounded twenty-two others. Against this backdrop, the infamous April 1999 school shootings at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, where two students murdered twelve other students and one teacher before killing themselves, seemed like the last straw. Within days, school after school across the nation installed metal detectors, located police at building entrances and in hallways, and began questioning or suspending students joking about committing violence. People everywhere wondered why the schools were becoming so violent and what could be done about it. A newspaper headline summarized their concern: “fear is spread around nation” (Zuckoff 1999).

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, depicted here, killed thirteen people at Columbine High School in 1999 before dying by suicide. Their massacre led people across the nation to question why violence was occurring in the schools and to wonder what could be done to reduce it.

Image courtesy of Columbine High School, http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Eric_harris_dylan_klebold.jpg

More recently, school shootings at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas and Annunciation Catholic School in Minneapolis, Minnesota sorrowed the nation. There were 39 school shootings in 2024 alone and 2022 witnessed a record high of 51 school shootings (Lieberman & Kim 2024). School shootings are of course not the only form of school violence, though they can be the most devastating as children lose their lives within seconds.

School Discipline and Discrimination

To reduce school violence and bullying, many school districts adopted strict policies that specify harsh punishments. A common policy involves zero-tolerance for weapons or even for minor infractions. This type of policy calls for automatic suspension or expulsion of a student who has anything resembling a weapon for any reason, including toy guns. This policy is often applied too rigidly. In one example, a 6-year-old boy in Delaware excitedly took his new camping utensil – a combination of knife, fork, and spoon –from Cub Scouts to school to use at lunch. He was suspended for having a knife and ordered to spend 45 days in reform school. His mother said her son certainly posed no threat to anyone at school, but school officials replied that their policy had to be strictly enforced because it is difficult to determine who actually poses a threat from who does not (Urbina 2009). In another case, a ninth grader took a knife and cigarette lighter away from a student who had used them to threaten a fellow classmate. The ninth grader was suspended for the rest of the school year for possessing a weapon, even though he had them only because he was protecting his classmate. According to a news story about this case, the school’s reaction was “vigilance to a fault” (Walker 2010).

Zero-tolerance or other very strict policies are also in place in many schools for offenses such as drug use and possession, fighting, and classroom disruption. However well intended these policies may be, research suggests that they are ineffective in deterring the behavior they are meant to prevent, and may even be counterproductive. As one review of this evidence puts it, “It is not clear that zero tolerance policies are succeeding in improving school safety. In fact, some evidence … suggests that these policies actually may have an adverse effect on student academic and behavioral outcomes” (Boccanfuso & Kuhfeld 2011: 1). When students are suspended, their grades may suffer, and their commitment to schooling may lower. These problems in turn increase their likelihood of engaging in delinquency. The expelled students find it difficult to get back into a school and eventually achieve a high school degree. Their behavior, too, may become more unlawful as a result, and they also are more likely to face unemployment and low-paying jobs. Zero-tolerance school discipline thus seems to do much more harm than good.

In addition to deterrence, another reason for the adoption of strict discipline policies has been to avoid the racial discrimination that occurs when school officials have discretion in deciding which students should be suspended or expelled (Skiba & Rausch 2006). In school districts with such discretion, Black students with weapons or “near weapons” (such as a small penknife) are more likely than white students with the same (near) weapons to be punished in this manner. However, a growing body of research finds that Black and Latino students are still more likely than white students to be suspended or expelled for similar misbehaviors such as having a weapon, fighting, cursing a teacher, and so on, even in school districts with very strict disciplinary policies (Welch & Payne 2010; Lewin 2012). Harsh school discipline as a solution to the problem of school violence is often racially discriminatory, and thus a problem itself rather than a true solution.