As we consider how to improve the nation’s education system, and especially how to improve outcomes for low-income students, students of color, and students in other marginalized groups, we need to keep in mind an important consideration: Good schooling can make an important difference for these students, and good teachers can greatly help (Chetty et al. 2011). However, a body of research demonstrates that students’ family and neighborhood backgrounds may matter more than the quality of schooling for their school performance (Downey & Gibbs 2012; Ladd & Fiske 2011). Good schooling, then, can only go so far in overcoming the disadvantages that students have before they enter kindergarten and the problems they continue to experience thereafter, particularly for low-income students and students of color. As one education writer observes:

In the sections that follow, we discuss some of the reform strategies including a proposed school reform agenda, which must be paired with other strategies discussed in prior chapters such as those to alleviate poverty. We also review examples of policy and practices that seek to improve education problems. We also take a unique approach, considering how an equity mindset can help address educational debt for marginalized students, as well as how liberation education advances social justice.

Reform Strategies

Reform strategies include both school reform and social reform. Below we briefly review the work of education experts who collectively offer a school reform agenda to improve education across the nation. Next we discuss social reform, that which occurs in society more broadly.

School Reform

Low-funded schools in low-income neighborhoods with decaying buildings, overworked teachers, and other concerns cannot be expected to produce students with adequate levels of academic achievement. It is thus critical, says poverty expert Mark Robert Rank, to do everything possible to provide a quality education to the nation’s poor children:

“To deny children the fundamental right to a decent education is both morally wrong and bad social policy. It flies in the face of the American concept of equality of opportunity… Countless studies have documented the immediate and lingering effects of disparate educational outcomes on later life. Improving public education for low-income children is absolutely essential” (2004: 208).

Education experts and organizations urge several measures to improve the nation’s schools and the education of children (García & Weiss 2017; Madland & Bunker 2011; Othering and Belonging Institute 2025; Rokosa 2011; Rothstein 2010; Smerdon & Borman 2009). These measures include the following:

- Provide more funding for schools, especially those in low-income neighborhoods

- Increase teachers’ pay to attract more highly qualified applicants

- Offer stronger professional development programing for teachers and staff

- Have smaller schools and smaller classrooms

- Repair decaying school buildings

- Invest more strongly and expand early childhood (pre-K) programs

- Provide comprehensive support (e.g., academic, health, nutrition, emotional) throughout children's schooling.

On the national level, these steps will cost billions of dollars, but this expenditure promises to have a significant payoff by saving money in the long run and reducing crime, health problems, and other social ills. In other words, prioritizing education in the national budget will improve society and reduce costs.

Children and Our Future

The Importance of Preschool and Summer Learning Programs for Low-Income Children

The first few years of life are absolutely critical for a child’s neurological and cognitive development. What happens, or doesn’t happen, before ages 5 and 6 can have lifelong consequences for a child’s educational attainment, adolescent behavior, and adult employment and family life. However, as this chapter and previous chapters emphasize, low-income children face many kinds of obstacles during this critical phase of their lives. Among other problems, their families are often filled with stressful life events that impair their physical and mental health and neurological development, and their parents read and talk to them much less on the average than wealthier parents do. These difficulties in turn lower their school performance and educational attainment, with negative repercussions continuing into adulthood.

To counteract these problems and enhance low-income children’s ability to do well in school, two types of programs have been repeatedly shown to be very helpful and even essential. The first is preschool, a general term for semiformal early learning programs that take place roughly between ages 3 and 5. As the name of the famous Head Start program implies, preschool is meant to help prepare low-income children for kindergarten and beyond. Depending on the program, preschool involves group instruction and play for children, developmental and health screening, and other components. Many European nations have high-quality preschool programs that are free or heavily subsidized, but these programs are, by comparison, much less prevalent in the United States and often more costly for parents.

Preschool in the United States has been shown to have positive benefits that extend well into adulthood. For example, children who participate in Head Start and certain other programs are more likely years later to graduate high school and attend college. They also tend to have higher salaries in their twenties, and they are less likely to engage in delinquency and crime.

The second program involves summer learning. Educators have discovered that summer is an important time for children’s learning. During the summer, children from middle-class and wealthier families tend to read books, attend summer camp and/or engage in other group activities, and travel with their parents. When they return to school in September, their reading and math skills are higher than when the summer began. In contrast, low-income children are much less likely to have these types of summer experiences, and those who benefitted from school lunch programs during the academic year often go hungry. As a result, their reading and math skills are lower when they return to school than when the summer began.

In response to this discovery, many summer learning programs have been established. They generally last from four to eight weeks and are held at schools, campgrounds, community centers, or other locations. Although these programs are still relatively new and not yet thoroughly studied, a recent review concluded that they “can be effective and are likely to have positive impacts when they engage students in learning activities that are hands-on, enjoyable, and have real-world applications.”

Preschool programs help children in the short and long term, and summer programs appear to have the same potential. Their expansion in the United States would benefit many aspects of American society. Because their economic benefits outweigh their economic costs, they are a “no-brainer” for comprehensive social reform efforts.

Sources: Child Trends 2011; Downey & Gibbs 2012; Garces, Thomas, & Currie 2003; Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Arteaga, & White 2011; Terzian & Moore 2009

One creative reform solution involves transitioning from our public school system to community schools. According to the Task Force on Next Generation Community Schools at the Brookings Institute (2021), "Community schools integrate, rather than silo, the services that children and families need, thus ensuring that funding for health, mental health, expanded learning time, and social services is well spent and effective" and in these schools "every family and community member is a partner in the effort to build on students’ strengths, engage them as learners, and enable them to reach their full potential." The four core pillars of community schooling include:

- Expanded and enriched learning time (such as after-school or summer programs and culturally relevant, real-world learning opportunities)

- Integrated student supports (such as for health care, nutrition, and housing)

- Active family and community engagement

- Collaborative leadership and practices (Brookings Institute 2021; Oakes, Maier, & Daniel 2017).

Another reform considers teacher evaluations. The 'No Child Left Behind' reform movement, begun by the federal government, uses students’ scores on standardized tests to assess the quality of their schooling. Perhaps inevitably, teachers’ performance ratings became increasingly tied to their students’ standardized test scores. However, because students’ test scores reflect their socioeconomic backgrounds and other non-school factors more than the quality of their schooling, these scores are not a good measure of teachers’ performance. As one education specialist summarizes this situation,

“Of all the goals of the education reform movement, none is more elusive than developing an objective model to assess teachers. Studies have shown that over time, test scores do not provide a consistent means of separating good from bad instructors. Test scores are an inadequate proxy for quality because too many factors outside the teachers’ control can influence student performance from year to year – or even from classroom to classroom during the same year” (Russell 2011).

Thus, other measures of learning and teacher evaluations should be implemented rather than relying on problematic standardized testing scores.

In short, good schools and good teachers matter. In particular, good elementary- and middle-school teachers have been shown to have a lifelong impact on their students: Students with good teachers are more likely years later to have higher college attendance rates and higher salaries in adulthood (Lowrey 2012).

Applying Social Research

Assessing the Impact of Small Class Size

Do elementary school students fare better if their classes have fewer students rather than more students? It is not easy to answer this important question, because any differences found between students in small classes and those in larger classes might not necessarily reflect class size. Rather, they may reflect other factors. For example, perhaps the most motivated, educated parents ask that their child be placed in a smaller class and that their school goes along with this request. Perhaps teachers with more experience favor smaller classes and are able to have their principals assign them to these classes, while new teachers are assigned larger classes. These and other possibilities mean that any differences found between the two class sizes might reflect the qualities and skills of students and/or teachers in these classes, and not class size itself.

For this reason, the ideal study of class size would involve random assignment of both students and teachers to classes of different size. Fortunately, a notable study of this type exists.

The study, named Project STAR (Student/Teacher Achievement Ratio), began in Tennessee in 1985 and involved 79 public schools and 11,600 students and 1,330 teachers who were all randomly assigned to either a smaller class (13–17 students) or a larger class (22–25 students). The random assignment began when the students entered kindergarten and lasted through third grade; in fourth grade, the experiment ended, and all the students were placed into the larger class size. The students are now in their early thirties, and many aspects of their educational and personal lives have been followed since the study began.

Some of the more notable findings of this multiyear study include the following:

- While in grades K–3, students in the smaller classes had higher average scores on standardized tests.

- Students who had been in the smaller classes continued to have higher average test scores in grades 4–7.

- Students who had been in the smaller classes were more likely to complete high school and also to attend college.

- Students who had been in the smaller classes were less likely to be arrested during adolescence.

- Students who had been in the smaller classes were more likely in their twenties to be married and to live in wealthier neighborhoods.

- White girls who had been in the smaller classes were less likely to have a teenage birth than white girls who had been in the larger classes.

Why did small class size have these benefits? Two reasons seem likely. First, in a smaller class, there are fewer students to disrupt the class by talking, fighting, or otherwise taking up the teacher’s time. More learning can thus occur in smaller classes. Second, kindergarten teachers are better able to teach noncognitive skills (cooperating, listening, sitting still) in smaller classes, and these skills can have an impact many years later.

Regardless of the reasons, it was the experimental design of Project STAR that enabled its findings to be attributed to class size rather than to other factors. Because small class size does seem to help in many ways, the United States should try to reduce class size in order to improve student performance and later life outcomes.

Sources: Chetty et al. 2011; Schanzenbach 2006

Social Reform

Students’ family and neighborhood contexts have a significant implication for educational attainment. To improve low-income students’ school performance, the nation must address the problems of poverty and social inequality. As two sociologists argue this point, “If we are serious about improving American children’s school performance, we will need to take a broader view of education policy. In addition to school reform, we must also aim to improve children’s lives where they spend the vast majority of their time – with their families and in their neighborhoods” (Downey & Gibbs 2012: 85).

Family and parenting contexts must be improved to enhance the educational performance and attainment of low-income students (Roksa & Potter 2011). Low-income parents are less likely to read and talk with their young children, often due to structural constraints such as the need to work multiple jobs, and this problem may impair their children’s cognitive and neurological development. Home visits and other efforts by professionals to encourage parents of infants and toddlers to engage in these activities regularly hold potential for improving their children’s ability to learn and do well in school. However, structural issues require structural solutions. For instance, increasing minimum wages, offering job skills training programs, and enhancing access to higher education would help low-income parents avoid having to work multiple jobs such that they could spend more time at home with their children engaging in the activities that would better prepare them for schooling.

Additionally, because the roots of school violence are also similar to the roots of youth violence outside of schools, measures that reduce youth violence should also reduce school violence. Such measures include early childhood prevention programs for youths at risk for developmental and behavioral problems, parenting training programs, and policies that provide income and jobs for families living in poverty.

Thus, social reform must occur alongside school reform. Other chapters have discussed strategies to reduce poverty and social inequality; these strategies would also help improve the school performance of students in marginalized groups.

Lessons from Other Societies

Successful Schooling in Finland

Finland is widely regarded as having perhaps the top elementary and secondary education system in the world. Its model of education offers several important lessons for US education. As a recent analysis of Finland’s schools put it, “The country’s achievements in education have other nations doing their homework.”

To understand the lessons to be learned from Finland, we should go back several decades to the 1970s, when Finland’s education system was below par, with its students scoring below the international average in mathematics and science. Moreover, urban schools in Finland outranked rural schools, and wealthy students performed much better than low-income students. More recently, Finnish students ranked at the top in international testing, and low-income students did almost as well as wealthy students.

Finland’s education system ranks so highly because it took several measures to improve its education system. First, and perhaps most important, Finland raised teachers’ salaries, required all teachers to have a three-year master’s degree, and paid all costs, including a living stipend, for the graduate education needed to achieve this degree. These changes helped to greatly increase the number of teachers, especially the number of highly qualified teachers, and Finland now has more teachers for every 1,000 residents than does the United States. Unlike the US, teaching is considered a highly prestigious profession in Finland, and the application process to become a teacher is very competitive. The college graduates who apply for one of Finland’s eight graduate programs in teaching typically rank in the top 10% of their class, and only 5–15% of their applications are accepted. A leading Finnish educator observed, “It’s more difficult getting into teacher education than law or medicine.” In contrast, US students who become teachers tend to have lower SAT scores than those who enter other professions, they only need a four-year degree, and their average salaries are lower than other professionals with a similar level of education.

Second, Finland revamped its curriculum to emphasize critical thinking skills, reduced the importance of scores on standardized tests and then eliminated standardized testing altogether, and eliminated academic tracking before tenth grade. Unlike the US, Finland no longer ranks students, teachers, or schools according to scores on standardized tests because these tests are no longer given.

Third, Finland built many more schools to enable the average school to have fewer students. Today the typical school has fewer than three hundred students, and class sizes are smaller than those found in the United States.

Fourth, Finland increased funding of its schools so that its schools are now well maintained and well equipped. Whereas many US schools are decrepit, Finnish schools are decidedly in good repair.

Finally, Finland provided free medical and dental care for children and their families and expanded other types of social services, including three years of paid maternity leave and subsidized day care, as the country realized that children’s health and home environment play critical roles in their educational achievement.

These and other changes helped propel Finland’s education system to a leading position among the world’s industrial nations. As the US ponders how best to improve its own education system, it may have much to learn from Finland’s approach to how children should learn.

Sources: Abrams 2011; Anderson 2011; Eggers & Calegari 2011; Hancock 2011; Ravitch 2012; Sahlberg 2011

Laws, Policies, and Practices

In addition to a general school reform agenda paired with other social reforms, specific laws and policies can reduce educational inequities and enhance student learning. Here we review one such law, outlined in a prior chapter, focusing on how that strategy has been weakened over the past several decades. We also consider examples of school programs that may be developed in practice and required in policy to address problems of education. Finally, we consider the practice of implementing an equity mindset to help reduce educational disparities.

Affirmative Action

As discussed in the Work and Economy chapter, affirmative action refers to consideration of people of color and of women in the institutions of work and education to compensate for the centuries of discrimination and lack of opportunities that they've experienced. However, court rulings, state legislation, and other efforts have weakened the strength of these considerations.

One of the major court rulings was the US Supreme Court’s decision in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978). Allan Bakke was a 35-year-old white man who had twice been rejected for admission into the medical school at the University of California, Davis. At the time he applied, UC–Davis had a policy of reserving 16 seats in its entering class of 100 for qualified people of color to make up for their underrepresentation in the medical profession. Bakke’s college grades and scores on the Medical College Admission Test were higher than those of the people of color admitted to UC–Davis both times Bakke applied. He sued for admission on the grounds that his rejection amounted to reverse racial discrimination on the basis of his being white (Stefoff 2005).

The case eventually reached the Supreme Court, which ruled 5–4 that Bakke must be admitted into the UC–Davis medical school because he had been unfairly denied admission on the basis of his race. As part of its historic but complex decision, the Court thus rejected the use of strict racial quotas in admission in order to make up for current underrepresentation and past discrimination, as it declared that no applicant could be excluded based solely on the applicant’s race. At the same time, however, the Court also declared that race may be used as one of the several criteria that admissions committees consider when making their decisions. For example, if a college desires racial diversity among its students, it may use race as an admissions criterion along with other factors such as grades and test scores.

Two more recent Supreme Court cases both involved the University of Michigan: Gratz v. Bollinger (2003) regarding the university’s undergraduate admissions, and Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) regarding the university’s law school admissions. In Grutter the Court reaffirmed the right of institutions of higher education to take race into account in the admissions process. In Gratz, however, the Court invalidated the university’s policy of awarding additional points to high school students of color as part of its use of a point system to evaluate applicants. The Court said that consideration of applicants needed to be more individualized than a point system allowed.

Even more recently, in the case Students for Fair Admissions v. President & Fellows of Harvard College and SFFA and v. University of North Carolina (2023), involving the oldest private and public universities in the nation (respectively), the Supreme Court effectively ended race-conscious admission programs at colleges, ruling that they may not consider race as one of many factors in deciding which of the qualified applicants is to be admitted.

Affirmative action was successful in expanding educational and workplace opportunities for people of color and women. For instance, research finds that Black students graduating from selective US colleges and universities after being admitted under affirmative action guidelines were as likely than their white counterparts to obtain professional degrees and to become involved in civic affairs (Bowen & Bok 1998). Additionally, today women comprise nearly 58% of students enrolled at the college level (The Chronicle of Higher Education 2025). The weakening of these considerations disrupts the institution of education's ability to serve individuals from underrepresented groups, and appears to have resulted in reduced college enrollment among Black and Latino people (Bhatia et al. 2025). If affirmative action cannot be used to help create equity in the institution of education (discussed further below), alternatives to these considerations must be developed, particularly to address racial disparities in higher education.

School Programs

Turning to grade school from higher education, one practice to better support students is to attend to the emotional and physical health needs of students, particularly low-income and otherwise marginalized children (Lowe 2011). Because of the obstacles children experience in their families and neighborhoods, including alcohol and drug misuse, hunger, psychological abuse, crime, and violence, their emotional and physical health may suffer. They cannot be expected to do well in school unless they are in good health. For this reason, many schools are now partnering with community health organizations and other agencies to address the emotional and physical health needs of schoolchildren, sometimes by establishing well-staffed and well-equipped health centers inside the schools. Another effort involves recess (yes, recess!), as evidence indicates that children are healthier and better behaved if they go out for recess for a sufficient amount of time.

One example of a solution to school violence and bullying is antibullying programs, which include regular parent meetings, strengthened playground supervision, and appropriate (proportionate and limited) discipline when warranted. Research indicates that these programs reduce bullying by 20–23% on average (Farrington & Ttofi 2009). Reductions in bullying may in turn help reduce the likelihood of school shootings such as with Columbine and Uvalde, because many of the students committing these acts of violence had been humiliated and bullied by other students (which in no way justifies these heinous acts, but points to the need to reduce school bullying). This reality also supports the prior strategy discussed, that students gain access to mental health agencies in their schools.

Other grade school programs such as the one described in the People Making a Difference box below have been found to improve educational outcomes.

People Making a Difference

Teaching Young Students about Science and Conservation

Since 1999, the Ocean Discovery Institute (ODI) has taught more than 40,000 public school students in a low-income San Diego neighborhood about the ocean and the environment. Most of the students are Latino, and a growing number are recent immigrants from Southeast Asia and East Africa. By learning about ocean science, the students also learn something about geology, physics, and other sciences. ODI’s program has grown over the years, and it now services more than 5,000 students annually in ten schools. To accomplish its mission, ODI engages in several kinds of activities.

- First, ODI instructors teach hands-on marine science activities to students in grades 3–6. They also consult closely with the schools’ teachers about the science curriculum taught in the schools.

- Second, ODI runs an after-school program in which they provide marine science–based lessons as well as academic, social, and college-entry support to approximately sixty students in grades 6–12.

- Third, ODI takes about twenty high school students every summer to the Sea of Cortez in Baja California, Mexico, for an intensive five-week research experience at a field research station. Before they do so, they are trained for several weeks in laboratory and field research procedures, and they also learn how to swim and snorkel. After they arrive at the field research station, they divide into three research teams; each team works on a different project under the guidance of ODI instructors and university and government scientists. A recent project, which won an award from the World Wildlife Fund, has focused on reducing the number of sea turtles that are accidentally caught in fishing nets.

The instruction provided by ODI has changed the lives of many students. Perhaps most notably, about 80 percent of the students who have participated in the after-school or summer program have attended a four-year college or university (with almost all declaring a major in one of the sciences), compared to less than one-third of students in their schools who have not participated in these programs. One summer program student, whose parents were deported by the government, recalls the experience fondly: “I have learned to become independent, and I pushed myself to try new things. Now I know I can overcome barriers and take chances… I am prepared to overcome challenges and follow my dreams.”

In 2011, ODI was one of three organizations that received the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Mathematics, and Engineering Mentoring. Several ODI officials and students traveled to the White House to take part in various events and accept the award from President Obama. As this award attests, the Ocean Discovery Institute is making a striking difference in the lives of low-income San Diego students. For further information, visit http://www.oceandiscoveryinstitute.org.

Source: Ocean Discovery Institute 2011

At the level of higher education, our discussion highlights the fact that social inequality in the larger society also plays out in colleges. The higher incompletion rates for students in marginalized groups in turn contribute to more social inequality. Admitting underrepresented students is the first step, but they must be supported while in as they may face many obstacles that students from more advantaged backgrounds are less likely to encounter. Programs such as TRIO (which assists low-income, first-generation, and disabled students in the transition to college), free mental health counseling, and school clubs for students of marginalized identities may improve retention and increase graduation rates.

Equity Mindset

Although generational educational debt cannot be solved by simple answers, applying an equity mindset rather than an equality mindset is a practice that can be part of an effective response. Equity is defined as everyone having what they need, even if it means that some need to be given more than others to have the same outcome. The drawing below illustrates the difference. You may have seen different variations of this concept as memes on social media. In other renditions, the final pane (on the right) is labeled 'Social Justice,' as it removes the barrier entirely. If you’d like to read more about it, this blog has a good explanation.

This drawing illustrates the differences between equality (everyone receives the same treatment), equity (everyone receives what they need), and social justice (the barrier to inequality is dismantled).

“Equality, Equity, Equity for All” by Katie Niemeyer from “Equity, Equality, and Fairness” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 1e is licensed under CC BY 4.0

The drawing explores what it takes to give each person what they need to enjoy the game. In the first panel of the drawing, they do not all get to have an equal experience despite being given the same supports. In the second drawing, all participants can have the viewing experience because the boxes have been equitably distributed. The third panel removes the structure that limits equitable access so that all participants can view the game without additional supports. The viewers get what they need easily – they have social justice. Removing all barriers to education is a lofty task; however, educators and school systems can approach education with an equity mindset.

Training school teachers, staff, and administrators to apply an equity mindset to all that they do could help close achievement gaps and address educational debt, by offering students what they need to succeed and centering students in marginalized groups in curriculum development and other school policies and processes.

Individual Agency and Collective Action

Education can reinforce social patterns of structural racism, sexism, heterosexism, ableism, and other discriminatory practices. However, education can also serve the purpose of liberation. Liberation education, that which is transformative for students and educators alike, is an approach to education that has been developed by individuals using their own agency and engaging in collective action to seek social justice in the institution. When people can read, write, and reason, they can ask critical questions about their lives. This power to question and engage in critical thinking is a door that opens to equity and justice.

Although we discuss liberation education as a strategy to address social problems within the institution of education, this section is of particular interest to anyone who may be an educator in the future. If you plan to go into teaching or training, listen up, this one is particularly pertinent to you!

To explore this approach, we turn to Paulo Freire, bell hooks, and educators and activists of the Open Oregon Project. Paulo Freire (pictured below) was an activist and educator in Brazil and internationally from 1940 to his death in 1997. He founded and ran adult literacy programs in the slums of northeast Brazil. When he taught reading and writing, he used everyday words and concepts that his students needed to know to live well, such as terms for cooking, childcare, or construction.

Paulo Freire was a Brazilian educator. Although he wasn’t a sociologist, his theories and methods transformed how some sociologists think about the transformational possibilities of education, including the authors of this textbook.

“Photo” by novohorizonte de Economia Solidaria is in the Public Domain

Freire’s most famous book is Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Pedagogy is the art, science, or profession of teaching. Freire looks at how teaching itself can empower oppressed people. In his book, he condemns the 'banking model' of education, which he defines as “the concept of education in which knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing” (Freire 1970). He argues that the banking model is the most common but least useful form of education. He writes:

"Education thus becomes an act of depositing, in which the students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor. Instead of communicating, the teacher issues communiques and makes deposits which the students patiently receive, memorize, and repeat… [Students] do, it is true, have the opportunity to become collectors or cataloguers of the things they store. But in the last analysis, it is the people themselves who are filed away through the lack of creativity, transformation, and knowledge in this (at best) misguided system" (Freire 1970: 72).

In contrast, Freire’s education model emphasizes dialogue, action, and reflection. In dialogue, the students and the teachers discuss what they are learning and how they see things working in the world. Each person contributes from their own experience and knowledge. He writes:

“To enter into dialogue presupposes equality amongst participants. Each must trust the others; there must be mutual respect and love (care and commitment). Each one must question what he or she knows and realize that through dialogue existing thoughts will change and new knowledge will be created.”

This dialogue is essential for learning and transformation but is insufficient as a social force. He argues that teaching and learning also require action and reflection. Engaging in the world and reflecting on what you learned, or praxis, is the true goal of education, creating a more equitable society by taking conscious action. As such, he notes:

“It is not enough for people to come together in dialogue in order to gain knowledge of their social reality. They must act together upon their environment in order critically to reflect upon their reality and so transform it through further action and critical reflection” (Freire 1970).

His institute still influences educators and thinkers worldwide about how to use education to promote social justice. If you’d like to learn more about how Freire’s social location influenced his theories, watch the video Paolo Freire and the Development of Critical Pedagogy.

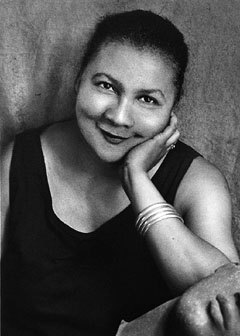

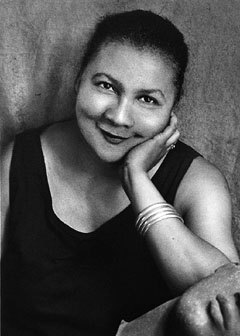

Black feminist author and educator bell hooks (pictured below) built on the work of Paulo Freire, feminist theorists, and her own experiences as a Black woman to expand on this vision of the radical transformative power of education.

bell hooks (whose name is intentionally lower case) is a Black author, educator, and activist who also argues that education can transform.

“bell hooks” by Kevin Andre Elliot is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In her book, Teaching to Transgress, hooks writes:

"For black folks teaching – educating – was fundamentally political because it was rooted in antiracist struggle. Indeed, my all black grade schools became the location where I experienced learning as revolution. ... Almost all our teachers at Booker T. Washington were black women. They were committed to nurturing intellect so that we could become scholars, thinkers, and cultural workers – black folks who used our 'minds.' We learned early that our devotion to learning, to a life of the mind, was a counter-hegemonic act, a fundamental way to resist every strategy of white racist colonization. Though they did not define or articulate these practices in theoretical terms, my teachers were enacting a revolutionary pedagogy of resistance that was profoundly anticolonial" (1994:2).

She asserts that education can be revolutionary in its approach and outcomes, because students learn in community. Social transformation occurs within the context of an engaged classroom of learners. Thus, educators and those who write education policy may view the classroom as a "communal place" which leads to "collective effort in creating and sustaining a learning community" (hooks 1994: 8). Like Freire, she argues that a classroom is a community and that teaching and learning transform the wider world. In this video, bell hooks talks about working with Paolo Freire: bell hooks on Freire.

These scholars and activists argue that education itself, when done in a transformational way, will create change in the student, teacher, classroom, and wider world. With this approach, we see that education becomes a tool for addressing social problems.

In a final example, we explore the project from which part of this Open Educational Resource (OER) textbook arose as an exercise in transformation in learning. The Open Oregon Educational Resources organization (logo pictured below), is a group of educators funded by the state of Oregon to create high-quality educational resources for students and make course materials more affordable and accessible for many students. Through this organization, the textbook Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice was developed, which was then incorporated into the textbook that you're reading now.

Open Oregon Educational Resources is a project dedicated to increasing student success in college by producing high-quality, free textbooks and courses for students in Oregon and beyond.

“Open Oregon Educational Resources Logo” by Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0

The project allows people normally excluded from research and textbook creation to be included in the process. They are a collective of students, teachers, researchers, activists, and artists weaving their stories into books and courses that reflect and explain their social lives. In their equity statement, they emphasize reducing barriers to course material access, centering equity in the selection, adaptation, or creation of course materials, and maintaining a commitment to:

- Ensuring diversity of representation within our team and the materials we distribute.

- Publishing materials that use accessible, clear language for our target audience.

- Sharing course materials that directly address and interrogate systems of oppression, equipping students and educators with the knowledge to do the same (Blicher et al. 2023).

Open Oregon’s approach is revolutionary, putting the power to create and share knowledge in the hands of ordinary people. This is education for liberation. These practices can dramatically reform the institution of education, reducing educational disparities and inequities and benefiting society at large by helping all individuals achieve their full potential.