15.4: Trauma Analysis and Bone Pathology

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 177779

TYPES OF TRAUMA

Within the field of anthropology, trauma is defined as an injury to living tissue caused by an extrinsic force or mechanism (Lovell 1997:139). Forensic anthropologists can assist a forensic pathologist by providing an interpretation of the course of events that led to skeletal trauma. Within the field of bioarchaeology, trauma analyses may contribute to a deeper understanding of past lifeways and interpersonal relationships. Within this section, the different types of trauma will be briefly outlined. Next, the timing of the injury (e.g., did trauma occur before, at or around, or after the time of death) will be discussed. Finally, the section will conclude with a discussion of how trauma interpretation is performed in the forensic anthropology laboratory.

Definition: trauma

An injury to living tissue caused by an extrinsic force or mechanism. (See Lovell 1997, 139.)

Typically, traumatic injury to bone is classified into one of four categories, defined by the trauma mechanism. A trauma mechanism refers to the force that produced the skeletal modification and can be classified as (1) sharp force, (2) blunt force, (3) projectile, or (4) thermal (burning). Each type of trauma, and the characteristic pattern(s) associated with that particular categorization, will be discussed below.

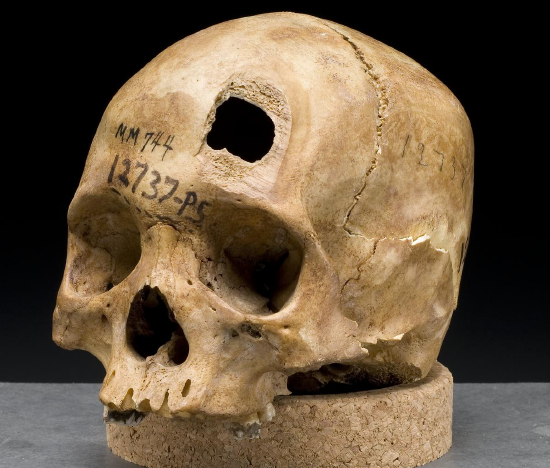

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Example of sharp-force trauma (sword wound) to the frontal bone.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Example of sharp-force trauma (sword wound) to the frontal bone.First, let’s consider sharp-force trauma, which is caused by a tool that is edged, pointed, or beveled—for example, a knife, saw, or machete (SWGANTH 2011). The patterns of injury resulting from sharp-force trauma include linear incisions created by a sharp, straight edge; punctures; and chop marks (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\); SWGANTH 2011). When observed under a microscope, an anthropologist can often determine what kind of tool created the bone trauma. For example, a power saw cut will be discernible from a manual saw cut.

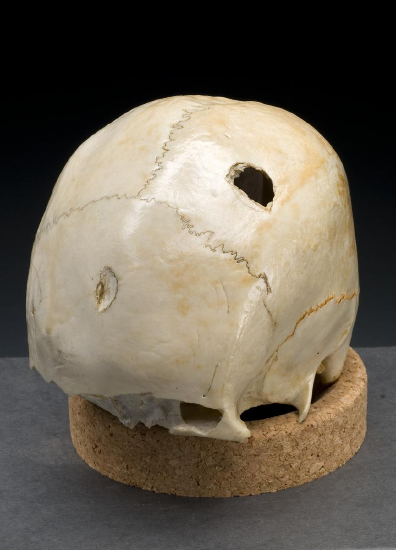

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Example of multiple blunt force impacts to the left parietal and frontal bones.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Example of multiple blunt force impacts to the left parietal and frontal bones.Second, blunt-force trauma is defined as “a relatively low-velocity impact over a relatively large surface area” (Galloway et al. 1999, 5). Blunt-force injuries can result from impacts from clubs, sticks, fists, and so forth. Blunt-force impacts typically leave an injury at the point of impact but can also lead to bending and deformation in other regions of the bone. Depressions, fractures, and deformation at and around the site of impact are all characteristics of blunt-force impacts (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). As with sharp-force trauma, an anthropologist attempts to interpret blunt-force injuries, providing information pertaining to the type of tool used, the direction of impact, the sequence of impacts, if more than one, and the amount of force applied.

Third, projectile trauma refers to high-velocity trauma, typically affecting a small surface area (Galloway et al. 1999, 6). Projectile trauma results from fast-moving objects such as bullets or shrapnel. It is typically characterized by penetrating defects or embedded materials (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). When interpreting injuries resulting from projectile trauma, an anthropologist can often offer information pertaining to the type of weapon used (e.g., rifle vs. handgun), relative size of the bullet (but not the caliber of the bullet), the direction the projectile was traveling, and the sequence of injuries if there are multiple present.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Example of projectile trauma with an entrance wound to the frontal bone and exit wound visible on the occipital.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Example of projectile trauma with an entrance wound to the frontal bone and exit wound visible on the occipital.Finally, thermal trauma is a bone alteration that results from bone exposure to extreme heat. Thermal trauma can result in cases of house or car fires, intentional disposal of a body in cases of homicidal violence, plane crashes, and so on. Thermal trauma is most often characterized by color changes to bone, ranging from yellow to black (charred) or white (calcined). Other bone alterations characteristic of thermal trauma include delamination (flaking or layering due to bone failure), shrinkage, fractures, and heat-specific burn patterning. When interpreting injuries resulting from thermal damage, an anthropologist can differentiate between thermal fractures and fractures that occurred before heat exposure, thereby contributing to the interpretation of burn patterning (e.g., was the individual bound or in a flexed position prior to the fire).

While there are characteristic patterns associated with the four categories of bone trauma, it is also important to note that these bone alterations do not always occur independently of different trauma types. An individual’s skeleton may present with multiple different types of trauma, such as a projectile wound and thermal trauma. Therefore, it is important that the anthropologist recognize the different types of trauma and interpret them appropriately.

Timing of Injury

Another important component of any anthropological trauma analysis is the determination of the timing of injury (e.g., when did the injury occur). Timing of injury is traditionally split into one of three categories: antemortem (before death), perimortem (at or around the time of death), and postmortem (after death). This classification system differs slightly from the classification system used by the pathologist because it specifically references the qualities of bone tissue and bone response to external forces. Therefore, the perimortem interval (at or around the time of death) means that the bone is still fresh and has what is referred to as a green bone response, which can extend past death by several weeks or even months. For example, in cold or freezing temperatures a body can be preserved for extended periods of time increasing the perimortem interval, while in desert climates decomposition is accelerated, thereby significantly decreasing the postmortem interval (Galloway et al. 1999, 12). Antemortem injuries (occurring well before death and not related to the death incident) are typically characterized by some level of healing, in the form of a fracture callus or unification of fracture margins. Finally, postmortem injuries (occurring after death, while bone is no longer fresh) are characterized by jagged fracture margins, resulting from a loss of moisture content during the decomposition process (Galloway et al. 1999, 16). In general, all bone traumas should be classified according to the timing of injury, if possible. This information will help the medical examiner or pathologist better understand the circumstances surrounding the decedent’s death, as well as events occurring during life and after the final disposition of the body.

Definition: antemortem trauma

Trauma occurring before death.

Definition: perimortem trauma

Trauma occurring at or around the time of death.

Definition: postmortem trauma

Trauma occurring after death.

The Role of the Forensic Anthropologist in Trauma Analysis

Within the medicolegal system, forensic anthropologists are often called upon by the medical examiner, forensic pathologist, or coroner to assist with an interpretation of trauma. The forensic anthropologist’s main focus in any trauma analysis is the underlying skeletal system—as well as, sometimes, cartilage. Analysis and interpretation of soft tissue injuries fall within the purview of the medical examiner or pathologist. It is also important to note that the main role of the forensic anthropologist is to provide information pertaining to skeletal injury to assist the medical examiner/pathologist in their final interpretation of injury. Forensic anthropologists do not hypothesize as to the cause of death of an individual. Instead, a forensic anthropologist’s report should include a description of the injury (e.g., trauma mechanism, number of injuries, location, timing of injury); documentation of the injury, which may be utilized in court testimony (e.g., photographs, radiographs, measurements); and, if applicable, a statement as to the condition of the body and state of decomposition, which may be useful for understanding the depositional context (e.g., how long has the body been exposed to the elements; was it moved or in its original location; are any of the alterations to bone due to environmental or faunal exposure instead of intentional human modification).

While there is a wide range of variation within the human skeletal system, bone development can also occur pathologically. Bone pathology can occur when there is excessive bone growth (osteoblastic activity or bone building) or bone is destroyed unnecessarily (osteoclastic activity or bone breakdown). Osteoblastic (bone building) and osteoclastic (bone destruction or breakdown) activities are normal processes of bone development, growth, and maintenance; however, when bone growth or breakdown exceeds what is necessary, the bony change can be classified as pathological, resulting in a bone pathology.

TYPES OF BONE PATHOLOGY

For the purposes of this chapter, we will focus on both osteoblastic and osteoclastic pathologies of the human skeleton. In addition to considering whether a pathology is osteoclastic or osteoblastic, it is also important to classify a pathology according to its origin. Bone pathologies can be classified in a number of ways, including:

- congenital: occurring in the developmental period, often hereditary;

- traumatic: resulting from extrinsic factors and forces;

- degenerative: causing the degeneration or breakdown of bone tissue;

- infectious: resulting from bacterial, viral, or fungal agents;

- circulatory: resulting from a disruption in the relationship between the skeletal and circulatory system;

- metabolic: resulting from nutrient deficiencies;

- endocrinological: caused by hormonal imbalances; and

- neoplastic: related to abnormal growth, both benign and malignant, of bone tissue.

For the remainder of this section, we will focus on six different bone pathologies: (1) osteosarcoma, (2) osteogenesis imperfecta, (3) rickets, (4) achondroplasia, (5) Paget’s disease of bone, and (6) diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH).

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma is a type of neoplastic bone pathology. Characterized by malignant tumors that begin within bone tissues, osteosarcoma is a primary bone cancer (meaning it begins directly in bone tissue, rather than spreading to bone from other body tissues). Malignant tumors associated with osteosarcoma usually occur during growth and development and are observed most often in adolescents and young adults (Ortner and Putschar 1981, 384). Tumors are most frequently observed near the ends of long bones (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\); Ortner and Putschar 1981, 384).

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) Osteosarcoma on a left human femur.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) Osteosarcoma on a left human femur.Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): X-ray of the forearms of an individual with osteogenesis imperfecta (note the presence of multiple healing fractures).

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): X-ray of the forearms of an individual with osteogenesis imperfecta (note the presence of multiple healing fractures).Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI) is a congenital bone pathology characterized by bones with low collagen content, leading to frequent fracturing (Ortner and Putschar 1981, 337). However, OI can also occur as a result of a spontaneous mutation. The disease is characterized by multiple fractures throughout the skeleton, particularly in the long bones (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). Depending on the type of OI, the disease is either manifest at birth or during childhood or adolescence (Ortner and Putschar 1981, 337). In addition to their susceptibility to easily fractured bones, individuals with OI are typically shorter in stature and may be subject to fracturing of tooth enamel and premature tooth loss (Ortner and Putschar 1981, 337).

Rickets

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Example of rickets in long bones of the leg.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Example of rickets in long bones of the leg.Rickets is a metabolic bone pathology resulting from a Vitamin D deficiency in childhood (Ortner and Putschar 1982, 273). Vitamin D is essential to the mineralization of bone tissue and is characterized by a wide variety of cranial and postcranial changes, including the following: asymmetrical deformities of the skull, bowing of the long bones, vertebral compression fractures, and a smaller, thicker pelvis (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\); Ortner and Putschar 1981, 273–278).

Achondroplasia

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): A cast of a complete skeleton of an adult female skeleton with achondroplasia.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): A cast of a complete skeleton of an adult female skeleton with achondroplasia.Achondroplasia is a congenital bone pathology resulting from an abnormality in the conversion of cartilage to bone and is the most common form of dwarfism (Ortner and Putschar 1981, 329). The skeletal manifestations of achondroplasia are most apparent in the long bones comprising the arms and legs, while the trunk is of relatively normal proportions in individuals with achondroplasia (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). On average, males with achondroplasia are approximately 4'4" tall and females are approximately 4'1" tall (NIH 2019).

Paget’s Disease of Bone

Paget’s disease of bone is a disease of unknown origin that causes bones to grow larger and weaker over time (NIH 2019). The disease is marked by both osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity, with excessive osteoclastic resorption followed by osteoblastic proliferation leading to unnecessary amounts of new woven bone (Ortner and Putschar 1981, 309). The disease typically does not appear until the fourth or fifth decade of life and is more common in males than females (Ortner and Putschar 1981, 309). Paget’s disease of bone can affect any bone, but the most commonly affected elements include the spine, pelvis, skull, and legs. The frequency of osteosarcoma is also higher among individuals with Paget’s disease of bone (NIH 2019).

Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH)

DISH is a bone pathology characterized by a hardening (calcification or buildup of calcium salts) of the ligaments and tendons of the vertebral column. While DISH is observed in other areas of the skeleton, the vertebral column is the most frequently affected region. DISH is more prevalent in males than females and typically is observed in older adults (50-plus years) (NIH 2019). Recent medical research suggests that DISH results from abnormal osteoblastic activity in the spine, leading to excessive bone growth (NIH 2019).

REFERENCES

Galloway, Alison. Broken Bones: Anthropological Analysis of Blunt Force Trauma. 1999. Springfield, IL: Charles C. THomas Publisher, LTD.

Lovell, Nancy C. 1997. “Trauma Analysis in Paleopathology.” Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 104 (S25): 139–170.

NIH U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2019. “Genetics Home Reference: Achondroplasia.” Last modified February 5, 2019. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/achondroplasia.

Ortner, Donald J., and Walter G. J. Putschar. 1981. Identification of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Scientific Working Group for Forensic Anthropology (SWGANTH). 2010b. “Sex Assessment.” Last modified June 3, 2010. www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2018/03/13/swganth_sex_assessment.pdf.

Scientific Working Group for Forensic Anthropology (SWGANTH). 2011. “Trauma Analysis.” Last modified May 27, 2011. www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2018/03/13/swganth_trauma.pdf.

FIGURE ATTRIBUTIONS

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) Skull sword trauma by the National Institutes of Health, Health & Human Services [19th Century Collection, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C. From exhibition “Visible Proofs: Forensic Views of the Body” U.S. National Library of Medicine] is in the public domain.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) Skull hammer trauma by the National Institutes of Health, Health & Human Services [19th Century Collection, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C. From exhibition “Visible Proofs: Forensic Views of the Body” U.S. National Library of Medicine] is in the public domain.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) Trauma: Gunshot Wounds by Smithsonian [exhibit: Written in Bone, How Bone Biographies Get Written] has no known copyright restrictions.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) Human Left Femur, Osteosarcoma by ©BoneClones is used by permission and available here is under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) Osteogenesis Imperfecta Type V by ShakataGaNai is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 License.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) Human Femur, Tibia and Fibula, Rickets by ©BoneClones is used by permission and available here is under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) Human Female Achondroplasia Dwarf Skeleton, Articulated by ©BoneClones is used by permission and available here is under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.