13.2: Industrial Revolutions

- Page ID

- 132422

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Industrial Revolution

Abundant fossil fuels and innovative machines powered and launched an era of accelerated change that continues to transform human society.

Smokestacks in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1890s © Bettmann/CORBIS

The Transformation of the World

Try to imagine what your life would be like without any machines working for you. If you were to make a list of the machines in your household and on your person; you may arrive at a surprising number. Now, imagine earlier generations during their childhood years. How did they move from place to place? How did they communicate? What foods did they eat?

At one time, humans fueled by the animals and plants they ate, and the wood they burned, provided most of the energy in use. Windmills and waterwheels captured some extra energy, but there was little in reserve. All life operated within the fairly immediate flow of energy from the Sun to Earth.

Everything changed during the First Industrial Revolution, which began around 1750. People found an extra source of energy with an incredible capacity for work. That source was fossil fuels — coal, oil, and natural gas — formed underground from the remains of plants and animals from much earlier geologic times. When these fuels were burned, they released energy that had been stored for hundreds of millions of years. Despite their relative abundance, these resources are not evenly distributed on Earth. Some places have much more than others, due to geographic factors and the diverse ecosystems that existed long ago.

Early Steam Engines

The story of the Industrial Revolution begins on the small island of Great Britain. By the early 18th century, people had used up most of their trees for building houses and ships, as well as for cooking and heating. In their search for something else to burn, they turned to the hunks of black stone (coal) that they found near the surface of the earth. Soon, they were digging deeper to mine it. The coal mines filled with water that needed to be removed, and horses pulling up bucketfuls proved slow going.

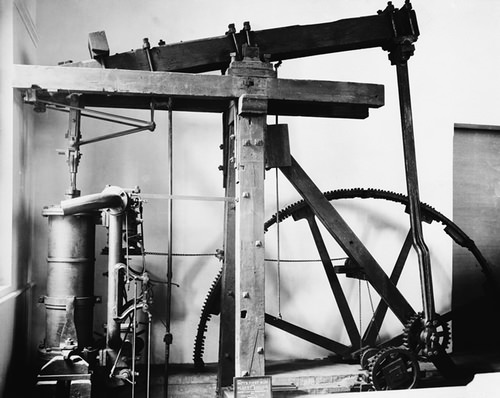

James Watt’s “Sun and Planet” steam engine © Bettmann/CORBIS

The problem was partially solved in 1776. James Watt (1736–1819) designed an engine in which burning coal produced steam, which drove a piston assisted by a partial vacuum. It proved to more quickly and efficiently pump water out of the coal mines, which allowed for better extraction of the natural resource. His patent ran out in 1800, and others added their designs to the product. By 1900, engines burned 10 times more efficiently than they had a hundred years before. (Fun fact.. Watt didn't have a completely new idea. There had been earlier steam engines in Britain, as well as China and in Turkey, that were used to turn the spit that roasts a lamb over a fire.)

At the outset of the 19th century, British colonies in North America were producing an abundance of cotton, using machines to spin the cotton thread on spindles and to weave it into cloth on looms. When they attached a steam engine to these machines, they could easily outproduce India, which was the world’s leading producer of cotton cloth. One steam engine could power many spindles and looms, so people started to leave their homes and work together in factories.

Around the same time, the British invented steam locomotives and steamships, which revolutionized travel. In 1851, they held the first world’s fair where telegraphs, sewing machines, revolvers, reaping machines, and steam hammers were demonstrated. The characteristics of an industrial society — smoke rising from factories, bigger cities and denser populations, railroads — could be seen in many places in Britain, the world's leading manufacturer of machinery.

Why Britain?

Britain wasn’t the only place that had deposits of coal. So why didn’t the Industrial Revolution begin in China, or somewhere else that boasted this natural resource? Did it start in isolation in Britain, or were there global forces at work that shaped it? Was it geography or cultural institutions that mattered most? Historians have vigorously debated these questions, amassing as much evidence as possible for their answers.

Possible reasons why industrialization began in Britain include:

- Shortage of wood and the abundance of convenient coal deposits

- Commercial-minded aristocracy; limited monarchy

- System of free enterprise; limited government involvement

- Government support for commercial projects, for a strong navy to protect ships

- Cheap cotton produced by enslaved people in North America

- High literacy rates

- Rule of law; protection of assets

- Valuable immigrants (Dutch, Jews, Huguenots [French Protestants])

Possible reasons why industrialization did not begin in China include:

- Location of China’s coal, which was in the north, while economic activity was centered in the south

- The rapid growth of population in China, giving less incentive for machines and more for labor-intensive methods

- Confucian ideals that valued stability and frowned upon experimentation and change

- Lack of Chinese government support for maritime explorations, thinking its empire seemed large enough to provide everything needed

- China’s focus on defending self from nomadic attacks from the north and west

Global forces influencing the development of industrialization in Britain include:

- Britain’s location on the Atlantic Ocean

- British colonies in North America, which provided land, labor, and markets

- Silver from the Americas, used in trade with China

- Social and ideological conditions in Britain, and new thoughts about the economy, that encouraged an entrepreneurial spirit

If you’re wondering what oil and natural gas were doing while coal was powering the Industrial Revolution, they had been discovered long before and were in use, but mostly as fuels for lamps and other light sources. It wasn’t until the mid-20th century that oil caught up — and surpassed — coal in use.

Calcutta Harbor, c. 1860 © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

The Spread of the Industrial Revolution

Britain tried to keep secret how its machines were made, but people took the techniques back to other countries. Sometimes they smuggled the machines out in rowboats to neighboring countries. The next countries to develop factories and railroads were Belgium, Switzerland, France, and the states that became Germany. Building a national railroad system proved an essential part of industrialization. Belgium began its railroads in 1834, France in 1842, Switzerland in 1847, and Germany in the 1850s.

In 1789, Samuel Slater emigrated from Britain to Rhode Island and set up the first textile factory on U.S soil. He did this from memory, having left Britain without notes or plans that could have been confiscated by British authorities. Next, between 1810-1812, Francis Cabot Cowell, of Massachusetts, visited Britain and returned to set up the first power loom and the first factory combining mechanical spinning and weaving in the States.

Railroad construction in the United States boomed from the 1830s to 1870s. The American Civil War (1861–65) was the first truly industrial war — the increasingly urbanized and factory-based North fighting against the agriculture-focused South. Industrialization grew explosively afterward. By 1900, the United States had overtaken Britain in manufacturing, producing 24 percent of the world’s output.

After 1870, both Russia and Japan had lost wars, and were forced to abolish their feudal systems and to compete in the industrializing world. In Japan, the monarchy proved flexible enough to survive through early industrialization. In Russia, a profoundly rural country, the Czar and the nobility undertook industrialization while trying to retain their dominance. Factory workers often worked 13-hour days without any legal rights. Discontent erupted repeatedly, and eventually, a revolution brought the Communist party to power in 1917.

Industrialized nations used strong armies and navies to colonize many parts of the world, gaining access to the raw materials needed for their factories. This practice is known as imperialism. In 1800, Europeans occupied or controlled about 34 percent of the land surface of the world; by 1914 this had risen to 84 percent. The story of Imperialism is part of the World History B course.

Consequences of the Industrial Revolution

Industrialization has not stopped, rather it continues to evolve. For many people, we are in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, although an equal number of people would probably disagree. Scientists argue that the Internet is the driving force.

How has the world changed between the 1st and 4th? In 1700, before the widespread use of fossil fuels, the world had a population of 670 million people. By 2011, the world’s population had reached 6.7 billion, a 10-fold increase in a mere 300 years. In the 20th century alone, the world’s economy grew 14-fold, the per capita income grew almost fourfold, and the use of energy expanded at least 13-fold. This kind of growth has never before occurred in human history.

The benefits of industrialization have come at a great cost. For one thing, the rate of change (acceleration) is now so rapid that individuals and social systems struggle to keep up. And strong arguments can be made about depersonalization in the age of mass production.

The increased complexity of the industrial system has also brought increased fragility. Industrialization depends on the interaction of many diverse components, any one of which could fail. We know that many of the essential components of the industrial system, and the natural resources it depends on, are being compromised — the soil, the oceans, the atmosphere, the underground water levels, plants, and animals are all at risk. Will growth continue unchecked, or are we approaching the end of an unsustainable industrial era? Whatever the future holds, we’ll be debating — and dealing with — the consequences of modernization for years to come.

Attribution: Material modified from CK-12 8.1 Industrial Revolution