2.3: Perception Process

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 115925

- Jason S. Wrench, Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter & Katherine S. Thweatt

- SUNY New Paltz & SUNY Oswego via OpenSUNY

↵

Learning Outcomes

- Describe perception and aspects of interpersonal perception.

- List and explain the three stages of the perception process.

- Understand the relationship between interpersonal communication and perception.

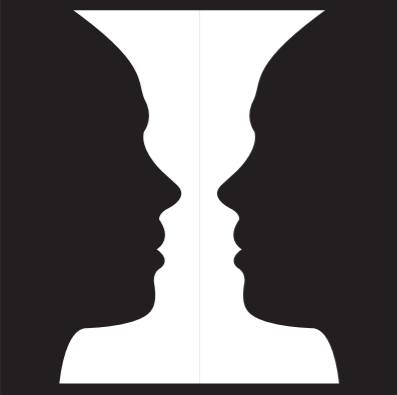

As you can see from the picture, how you view something is also how you will describe and define it. Your perception of something will determine how you feel about it and how you will communicate about it. In the picture above, do you see it as a six or a nine? Why did you answer the way that you did?

Your perceptions affect who you are, and they are based on your experiences and preferences. If you have a horrible experience with a restaurant, you probably won’t go to that restaurant in the future. You might even tell others not to go to that restaurant based on your personal experience. Thus, it is crucial to understand how perceptions can influence others.

Sometimes the silliest arguments occur with others because we don’t understand their perceptions of things. Just like the illustration shows, it is important to make sure that you see things the same way that the other person does. In other words, put yourself in their shoes and see it from their perspective before jumping to conclusions or getting upset. That person might have a legitimate reason why they are not willing to concede with you.

Perception

Many of our problems in the world occur due to perception, or the process of acquiring, interpreting, and organizing information that comes in through your five senses. When we don’t get all the facts, it is hard to make a concrete decision. We have to rely on our perceptions to understand the situation. In this section, you will learn tools that can help you understand perceptions and improve your communication skills. As you will see in many of the illustrations on perception, people can see different things. In some of the pictures, some might only be able to see one picture, but there might be others who can see both images, and a small amount might be able to see something completely different from the rest of the class.

Many famous artists over the years have played with people’s perceptions. Figure 2.3.2 is an example of three artists’ use of twisted perceptions. The first picture was initially created by Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin and is commonly called The Rubin Vase. Essentially, you have what appears to either be a vase (the white part) or two people looking at each other (the black part). This simple image is both two images and neither image at the same time. The second work of art is Charles Allan Gilbert’s (1892) painting “All is Vanity.” In this painting, you can see a woman sitting staring at herself in the mirror. At the same time, the image is also a giant skull. Lastly, we have William Ely Hill (1915) “My Wife and My Mother-in-Law,” which may have been loosely based on an 1888 German postcard. In Hill’s painting, you have two different images, one of a young woman and one of an older woman. The painting was initially published in an American humor magazine called Puck. The caption “They are both in this picture — Find them” ran alongside the picture. These visual images are helpful reminders that we don’t always perceive things in the same way as those around us. There are often multiple ways to view and understand the same set of events.

When it comes to interpersonal communication, each time you talk to other people, you present a side of yourself. Sometimes this presentation is a true representation of yourself, and other times it may be a fake version of yourself. People present themselves how they want others to see them. Some people present themselves positively on social media, and they have wonderful relationships. Then, their followers or fans get shocked to learn when those images are not true to what is presented. If we only see one side of things, we might be surprised to learn that things are different. In this section, we will learn that the perception process has three stages: attending, organizing, and interpreting.

Attending

The first step of the perception process is to select what information you want to pay attention to or focus on, which is called attending. You will pay attention to things based on how they look, feel, smell, touch, and taste. At every moment, you are obtaining a large amount of information. So, how do you decide what you want to pay attention to and what you choose to ignore? People will tend to pay attention to things that matter to them. Usually, we pay attention to things that are louder, larger, different, and more complex to what we ordinarily view.

When we focus on a particular thing and ignore other elements, we call it selective perception. For instance, when you are in love, you might pay attention to only that special someone and not notice anything else. The same thing happens when we end a relationship, and we are devasted, we might see how everyone else is in a great relationship, but we aren’t.

There are a couple of reasons why you pay attention to certain things more so than others. The first reason why we pay attention to something is because it is extreme or intense. In other words, it stands out of the crowd and captures our attention, like an extremely good looking person at a party or a big neon sign in a dark, isolated town. We can’t help but notice these things because they are exceptional or extraordinary in some way.

Second, we will pay attention to things that are different or contradicting. Commonly, when people enter an elevator, they face the doors. Imagine if someone entered the elevator and stood with their back to the elevator doors staring at you. You might pay attention to this person more than others because the behavior is unusual. It is something that you don’t expect, and that makes it stand out more to you. On another note, different could also be something that you are not used to or something that no longer exists for you. For instance, if you had someone very close to you pass away, then you might pay more attention to the loss of that person than to anything else. Some people grieve for an extended period because they were so used to having that person around, and things can be different since you don’t have them to rely on or ask for input.

The third thing that we pay attention to is something that repeats over and over again. Think of a catchy song or a commercial that continually repeats itself. We might be more alert to it since it repeats, compared to something that was only said once.

The fourth thing that we will pay attention to is based on our motives. If we have a motive to find a romantic partner, we might be more perceptive to other attractive people than normal, because we are looking for romantic interests. Another motive might be to lose weight, and you might pay more attention to exercise advertisements and food selection choices compared to someone who doesn’t have the motive to lose weight. Our motives influence what we pay attention to and what we ignore.

The last thing that influences our selection process is our emotional state. If we are in an angry mood, then we might be more attentive to things that get us angrier. As opposed to, if we are in a happy mood, then we will be more likely to overlook a lot of negativity because we are already happy. Selecting doesn’t involve just paying attention to certain cues. It also means that you might be overlooking other things. For instance, people in love will think their partner is amazing and will overlook a lot of their flaws. This is normal behavior. We are so focused on how wonderful they are that we often will neglect the other negative aspects of their behavior.

Organizing

Look again at the three images in Figure 2.3.2. What were the first things that you saw when you looked at each picture? Could you see the two different images? Which image was more prominent? When we examine a picture or image, we engage in organizing it in our head to make sense of it and define it. This is an example of organization. After we select the information that we are paying attention to, we have to make sense of it in our brains. This stage of the perception process is referred to as organization. We must understand that the information can be organized in different ways. After we attend to something, our brains quickly want to make sense of this data. We quickly want to understand the information that we are exposed to and organize it in a way that makes sense to us.

There are four types of schemes that people use to organize perceptions.17 First, physical constructs are used to classify people (e.g., young/old; tall/short; big/small). Second, role constructs are social positions (e.g., mother, friend, lover, doctor, teacher). Third, interaction constructs are the social behaviors displayed in the interaction (e.g., aggressive, friendly, dismissive, indifferent). Fourth, psychological constructs are the dispositions, emotions, and internal states of mind of the communicators (e.g., depressed, confident, happy, insecure). We often use these schemes to better understand and organize the information that we have received. We use these schemes to generalize others and to classify information.

Let’s pretend that you came to class and noticed that one of your classmates was wildly waving their arms in the air at you. This will most likely catch your attention because you find this behavior strange. Then, you will try to organize or makes sense of what is happening. Once you have organized it in your brain, you will need to interpret the behavior.

Interpreting

The final stage of the perception process is interpreting. In this stage of perception, you are attaching meaning to understand the data. So, after you select information and organize things in your brain, you have to interpret the situation. As previously discussed in the above example, your friend waves their hands wildly (attending), and you are trying to figure out what they are communicating to you (organizing). You will attach meaning (interpreting). Does your friend need help and is trying to get your attention, or does your friend want you to watch out for something behind you?

We interpret other people’s behavior daily. Walking to class, you might see an attractive stranger smiling at you. You could interpret this as a flirtatious behavior or someone just trying to be friendly. Scholars have identified some factors that influence our interpretations:18

Personal Experience

First, personal experience impacts our interpretation of events. What prior experiences have you had that affect your perceptions? Maybe you heard from your friends that a particular restaurant was really good, but when you went there, you had a horrible experience, and you decided you never wanted to go there again. Even though your friends might try to persuade you to try it again, you might be inclined not to go, because your past experience with that restaurant was not good.

Another example might be a traumatic relationship break up. You might have had a relational partner that cheated on you and left you with trust issues. You might find another romantic interest, but in the back of your mind, you might be cautious and interpret loving behaviors differently, because you don’t want to be hurt again.

Involvement

Second, the degree of involvement impacts your interpretation. The more involved or deeper your relationship is with another person, the more likely you will interpret their behaviors differently compared to someone you do not know well. For instance, let’s pretend that you are a manager, and two of your employees come to work late. One worker just happens to be your best friend and the other person is someone who just started and you do not know them well. You are more likely to interpret your best friend’s behavior more altruistically than the other worker because you have known your best friend for a longer period. Besides, since this person is your best friend, this implies that you interact and are more involved with them compared to other friends.

Expectations

Third, the expectations that we hold can impact the way we make sense of other people’s behaviors. For instance, if you overheard some friends talking about a mean professor and how hostile they are in class, you might be expecting this to be true. Let’s say you meet the professor and attend their class; you might still have certain expectations about them based on what you heard. Even those expectations might be completely false, and you might still be expecting those allegations to be true.

Assumptions

Fourth, there are assumptions about human behavior. Imagine if you are a personal fitness trainer, do you believe that people like to exercise or need to exercise? Your answer to that question might be based on your assumptions. If you are a person who is inclined to exercise, then you might think that all people like to work out. However, if you do not like to exercise but know that people should be physically fit, then you would more likely agree with the statement that people need to exercise. Your assumptions about humans can shape the way that you interpret their behavior. Another example might be that if you believe that most people would donate to a worthy cause, you might be shocked to learn that not everyone thinks this way. When we assume that all humans should act a certain way, we are more likely to interpret their behavior differently if they do not respond in a certain way.

Relational Satisfaction

Fifth, relational satisfaction will make you see things very differently. Relational satisfaction is how satisfied or happy you are with your current relationship. If you are content, then you are more likely to view all your partner’s behaviors as thoughtful and kind. However, if you are not satisfied in your relationship, then you are more likely to view their behavior has distrustful or insincere. Research has shown that unhappy couples are more likely to blame their partners when things go wrong compared to happy couples.19

Conclusion

In this section, we have discussed the three stages of perception: attending, organizing, and interpreting. Each of these stages can occur out of sequence. For example, if your parent/guardian had a bad experience at a car dealership based on their interpretation (such as “They overcharged me for the car and they added all these hidden fees.”), then it can influence their future selection (looking for credible and highly rated car dealerships, and then your parent/guardian can organize the information (car dealers are just trying to make money, the assumption is that they think most customers don’t know a lot about cars). Perception is a continuous process, and it is very hard to determine the start and finish of any perceptual differences.

Key Takeaways

- Perception involves attending, organizing, and interpreting.

- Perception impacts communication.

- Attending, organizing, and interpreting have specific definitions, and each is impacted by multiple variables.

Exercises

- Take a walk to a place you usually go to on campus or in your neighborhood. Before taking your walk, mentally list everything that you will see on your walk. As you walk, notice everything on your path. What new things do you notice now that you are deliberately “attending” to your environment?

- What affects your perception? Think about where you come from and your self-concept. How do these two factors impact how you see the world?

- Look back at a previous text or email that you got from a friend. After reading it, do you have a different interpretation of it now compared to when you first got it? Why? Think about how interpretation can impact communication if you didn’t know this person. How does it differ?