2.4: Models of Interpersonal Communication

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 115926

- Jason S. Wrench, Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter & Katherine S. Thweatt

- SUNY New Paltz & SUNY Oswego via OpenSUNY

Learning Outcomes

- Differentiate among and describe the various action models of interpersonal communication.

- Differentiate among and describe the various interactional models of interpersonal communication.

- Differentiate among and describe the various transactional models of interpersonal communication.

In the world of communication, we have several different models to help us understand what communication is and how it works. A model is a simplified representation of a system (often graphic) that highlights the crucial components and connections of concepts, which are used to help people understand an aspect of the real-world. For our purposes, the models have all been created to help us understand how real-world communication interactions occur. The goal of creating models is three-fold:

- to facilitate understanding by eliminating unnecessary components,

- to aid in decision making by simulating “what if” scenarios, and

- to explain, control, and predict events on the basis of past observations.20

Over the next few paragraphs, we’re going to examine three different types of models that communication scholars have proposed to help us understand interpersonal interactions: action, interactional, and transactional.

Action Models

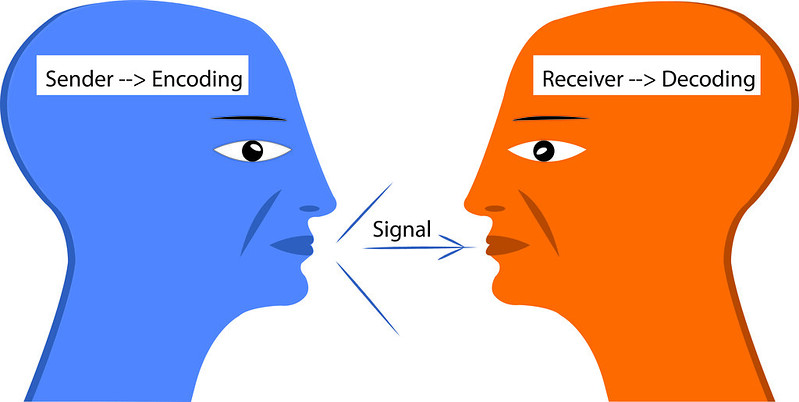

In this section, we will be discussing different models to understand interpersonal communication. The purpose of using models is to provide visual representations of interpersonal communication and to offer a better understanding of how various scholars have conceptualized it over time. The first type of model we’ll be exploring are action models, or communication models that view communication as a one-directional transmission of information from a source or sender to some destination or receiver.

Shannon-Weaver Model

Shannon and Weaver were both engineers for the Bell Telephone Labs. Their job was to make sure that all the telephone cables and radio waves were operating at full capacity. They developed the Shannon-Weaver model, which is also known as the linear communication model (Weaver & Shannon, 1963).21 As indicated by its name, the scholars believed that communication occurred in a linear fashion, where a sender encodes a message through a channel to a receiver, who will decode the message. Feedback is not immediate. Examples of linear communication were newspapers, radio, and television.

Weaver model, which is also known as the linear communication model (Weaver & Shannon, 1963).21 As indicated by its name, the scholars believed that communication occurred in a linear fashion, where a sender encodes a message through a channel to a receiver, who will decode the message. Feedback is not immediate. Examples of linear communication were newspapers, radio, and television.

Early Schramm Model

The Shannon-Weaver model was criticized because it assumed that communication always occurred linearly. Wilbur Schram (1954) felt that it was important to notice the impact of messages.22 Schramm’s model regards communication as a process between an encoder and a decoder. Most importantly, this model accounts for how people interpret the message. Schramm argued that a person’s background, experience, and knowledge are factors that impact interpretation. Besides, Schramm believed that the messages are transmitted through a medium. Also, the decoder will be able to send feedback about the message to indicate that the message has been received. He argued that communication is incomplete unless there is feedback from the receiver. According to Schramm’s model, encoding and decoding are vital to effective communication. Any communication where decoding does not occur or feedback does not happen is not effective or complete.

Berlo’s SMCR Model

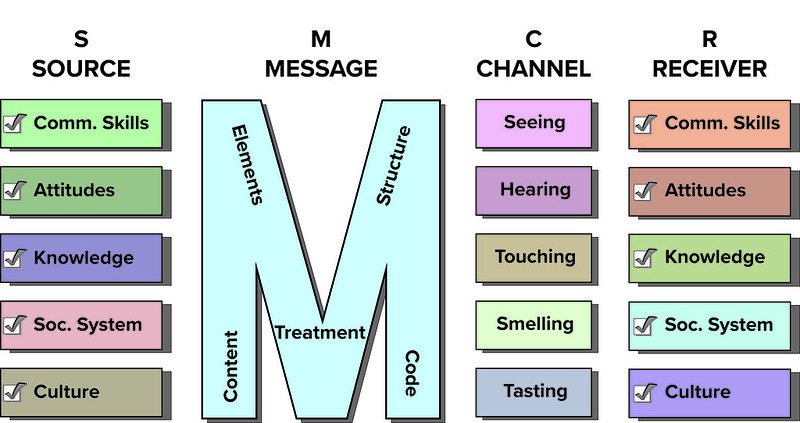

David K. Berlo (1960)23 created the SMCR model of communication. SMCR stands for sender, message, channel, receiver. Berlo’s model describes different components of the communication process. He argued that there are three main parts of all communication, which is the speaker, the subject, and the listener. He maintained that the listener determines the meaning of any message.

In regards to the source or sender of the message, Berlo identified factors that influence the source of the message. First, communication skills refer to the ability to speak or write. Second, attitude is the person’s point-of-view, which may be influenced by the listener. The third is whether the source has requisite knowledge on a given topic to be effective. Fourth, social systems include the source’s values, beliefs, and opinions, which may influence the message.

Next, we move onto the message portion of the model. The message can be sent in a variety of ways, such as text, video, speech. At the same time, there might be components that influence the message, such as content, which is the information being sent. Elements refer to the verbal and nonverbal behaviors of how the message is sent. Treatment refers to how the message was presented. The structure is how the message was organized. Code is the form in which the message was sent, such as text, gesture, or music.

The channel of the message relies on the basic five senses of sound, sight, touch, smell, and taste. Think of how your mother might express her love for you. She might hug you (touch) and say, “I love you” (sound), or make you your favorite dessert (taste). Each of these channels is a way to display affection.

The receiver is the person who decodes the message. Similar to the models discussed earlier, the receiver is at the end. However, Berlo argued that for the receiver to understand and comprehend the message, there must be similar factors to the sender. Hence, the source and the receiver have similar components. In the end, the receiver will have to decode the message and determine its meaning. Berlo tries to present the model of communication as simple as possible. His model accounts for variables that will obstruct the interpretation of the model.

Interaction Models

In this section, we’re going to explore the next evolution of communication models, interaction models. Interaction models view the sender and the receiver as responsible for the effectiveness of the communication. One of the biggest differences between the action and interaction models is a heightened focus on feedback.

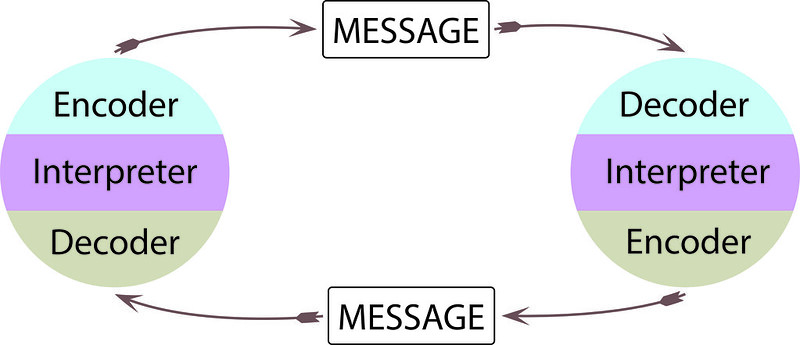

Osgood and Schramm Model

Osgood-Schramm’s model of communication is known as a circular model because it indicates that messages can go in two directions.24 Hence, once a person decodes a message, then they can encode it and send a message back to the sender. They could continue encoding and decoding into a continuous cycle. This revised model indicates that: 1) communication is not linear, but circular; 2) communication is reciprocal and equal; 3) messages are based on interpretation; 4) communication involves encoding, decoding, and interpreting. The benefit of this model is that the model illustrates that feedback is cyclical. It also shows that communication is complex because it accounts for interpretation. This model also showcases the fact that we are active communicators, and we are active in interpreting the messages that we receive.

Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson Model

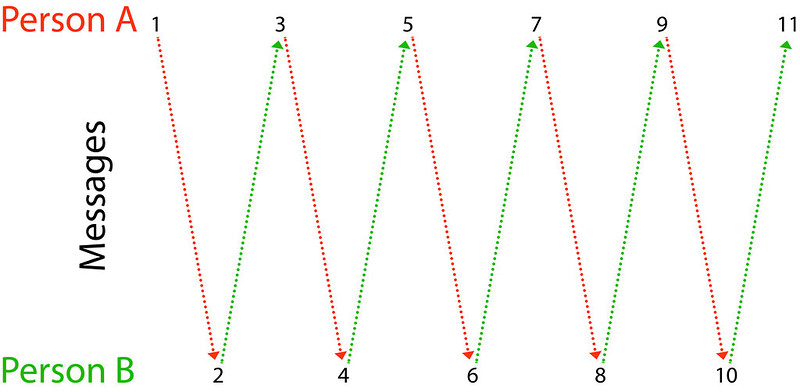

Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson argued that communication is continuous.25 The researchers argued that communication happens all the time. Every time a message is sent, then a message is returned, and it continues from Person A to Person B until someone stops. Feedback is provided every time that Person A sends a message. With this model, there are five axioms.

First, one cannot, not communicate. This means that everything one does has communicative value. Even if people do not talk to each other, then it still communicates the idea that both parties do not want to talk to each other. The second axiom states that every message has a content and relationship dimension. Content is the informational part of the message or the subject of discussion. The relationship dimension refers to how the two communicators feel about each other. The third axiom is how the communicators in the system punctuate their communicative sequence. The scholars observed that every communication event has a stimulus, response, and reinforcement. Each communicator can be a stimulus or a response. Fourth, communication can be analog or digital. Digital refers to what the words mean. Analogical is how the words are said or the nonverbal behavior that accompanies the message. The last axiom states that communication can be either symmetrical or complementary. This means that both communicators have similar power relations, or they do not. Conflict and misunderstandings can occur if the communicators have different power relations. For instance, your boss might have the right to fire you from your job if you do not professionally conduct yourself.

Transaction Models

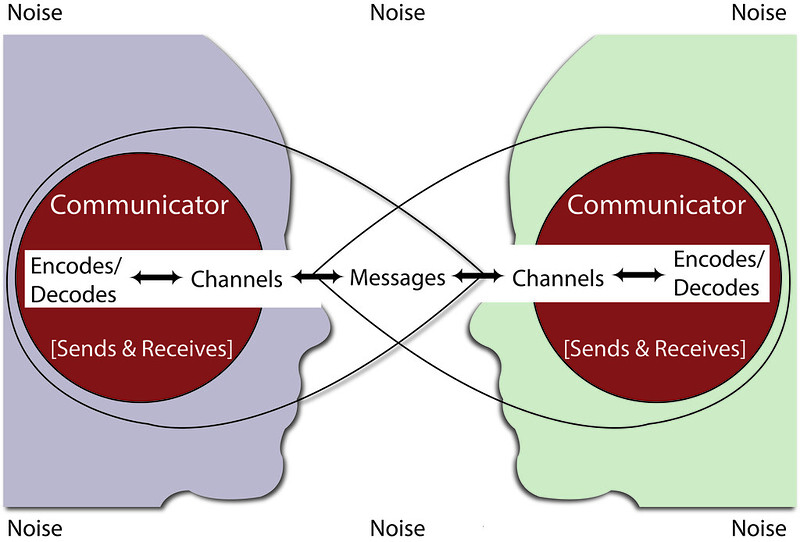

The transactional models differ from the interactional models in that the transactional models demonstrate that individuals are often acting as both the sender and receiver simultaneously. Basically, sending and receiving messages happen simultaneously.

Barnlund’s Transactional Model

In 1970, Dean C. Barnlund created the transactional model of communication to understand basic interpersonal communication.26 Barnlund argues that one of the problems with the more linear models of communication is that they resemble mediated messages. The message gets created, the message is sent, and the message is received. For example, we write an email, we send an email, and the email is read. Instead, Barnlund argues that during interpersonal interactions, we are both sending and receiving messages simultaneously. Out of all the other communication models, this one includes a multi-layered feedback system. We can provide oral feedback, but our nonverbal communication (e.g., tone of voice, eye contact, facial expressions, gestures) is equally important to how others interpret the messages we are sending we use others’ nonverbal behaviors to interpret their messages. As such, in any interpersonal interaction, a ton of messages are sent and received simultaneously between the two people.

The Importance of Cues

The main components of the model include cues. There are three types of cues: public, private, and behavioral. Public cues are anything that is physical or environmental. Private cues are referred to as the private objects of the orientation, which include the senses of a person. Behavioral cues include nonverbal and verbal cues.

The Importance of Context

Furthermore, the transactional model of communication has also gone on to represent that three contexts coexist during an interaction:

- Social Context: The rules and norms that govern how people communicate with one another.

- Cultural Context: The cultural and co-cultural identities people have (e.g., ability, age, biological sex, gender identity, ethnicity, nationality, race, sexual orientation, social class).

- Relational Context: The nature of the bond or emotional attachment between two people (e.g., parent/guardian-child, sibling-sibling, teacher-student, health care worker-client, best friends, acquaintances).

Through our interpersonal interactions, we create social reality, but all of these different contexts impact this reality.

The Importance of Noise

Another important factor to consider in Barnlund’s Transactional Model is the issue of noise, which includes things that disturb or interrupt the flow of communication. Like the three contexts explored above, there are another four contexts that can impact our ability to interact with people effectively:27

- Physical Context: The physical space where interaction is occurring (office, school, home, doctor’s office, is the space loud, is the furniture comfortable, etc.).

- Physiological Context: The body’s responses to what’s happening in its environment.

a. Internal: Physiological responses that result because of our body’s internal processes (e.g., hunger, a headache, physically tired).

b. External: Physiological responses that result because of external stimuli within the environment (e.g., are you cold, are you hot, the color of the room, are you physically comfortable). - Psychological Context: How the human mind responds to what’s occurring within its environment (e.g., emotional state, thoughts, perceptions, intentions, mindfulness).

- Semantic Context: The possible understanding and interpretation of different messages sent (e.g., someone’s language, size of vocabulary, effective use of grammar).

In each of these contexts, it’s possible to have things that disturb or interrupts the flow of communication. For example, in the physical context, hard plastic chairs can make you uncomfortable and not want to sit for very long talking to someone. Physiologically, if you have a headache (internal) or if a room is very hot, it can make it hard to concentrate and listen effectively to another person. Psychologically, if we just broke up with our significant other, we may find it difficult to sit and have a casual conversation with someone while our brains are running a thousand miles a minute. Semantically, if we don’t understand a word that someone uses, it can prevent us from accurately interpreting someone’s messages. When you think about it, with all the possible interference of noise that exists within an interpersonal interaction, it’s pretty impressive that we ever get anything accomplished.

More often than not, we are completely unaware of how these different contexts create noise and impact our interactions with one another during the moment itself. For example, think about the nature of the physical environments of fast-food restaurants versus fine dining establishments. In fast-food restaurants, the décor is bright, the lighting is bright, the seats are made of hard surfaces (often plastic), they tend to be louder, etc. This noise causes people to eat faster and increase turnover rates. Conversely, fine dining establishments have tablecloths, more comfortable chairs, dimmer lighting, quieter dining, etc. The physical space in a fast-food restaurant hurries interaction and increases turnover. The physical space in the fine dining restaurant slows our interactions, causes us to stay longer, and we spend more money as a result. However, most of us don’t pay that much attention to how physical space is impacting us while we’re having a conversation with another person.

Although we used the external environment here as an example of how noise impacts our interpersonal interactions, we could go through all of these contexts and discuss how they impact us in ways of which we’re not consciously aware. We’ll explore many of these contexts throughout the rest of this book.

Transaction Principles

As you can see, these models of communication are all very different. They have similar components, yet they are all conveyed very differently. Some have features that others do not. Nevertheless, there are transactional principles that are important to learn about interpersonal communication.

Communication is Complex

People might think that communication is easy. However, there are a lot of factors, such as power, language, and relationship differences, that can impact the conversation. Communication isn’t easy, because not everyone will have the same interpretation of the message. You will see advertisements that some people will love and others will be offended by. The reason is that people do not identically receive a message.

Communication is Continuous

In many of the communication models, we learned that communication never stops. Every time a source sends a message, a receiver will decode it, and it goes back-and-forth. It is an endless cycle, because even if one person stops talking, then they have already sent a message that the communication needs to end. 61 Interpersonal Communication As a receiver, you can keep trying to send messages, or you can stop talking as well, which sends the message to the other person that you also want to stop talking.

Communication is Dynamic

With new technology and changing times, we see that communication is constantly changing. Before social media, people interacted very differently. Some people have suggested that social media has influenced how we talk to each other. The models have changed over time because people have also changed how they communicate. People no longer use the phone to call other people; instead, they will text message others because they find it easier and less evasive.

Final Note

The advantage of this model is it shows that there is a shared field of experience between the sender and receiver. The transactional model shows that messages happen simultaneously with noise. However, the disadvantages of the model are that it is complex, and it suggests that the sender and receiver should understand the messages that are sent to each other.

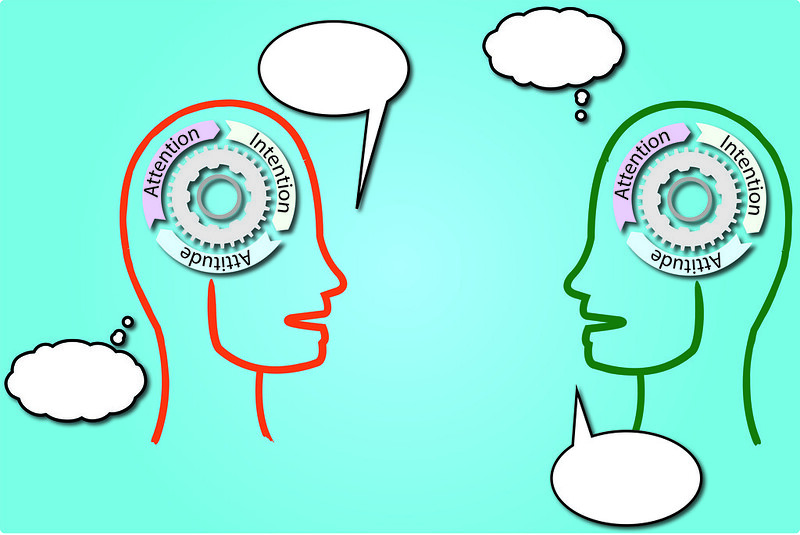

Towards a Model of Mindful Communication

So, what ultimately does a model of mindful communication look like? Well, to start, we think mindful communication is very similar to the transactional model of human communication. All of the facets of transactional communication can be applied in this context as well. The main addition to the model of mindful communication is coupling what we already know about the transactional model with what we learned in Chapter 1 about mindfulness. In Figure 2.4.7, we have combined the transactional model with Shauna Shapiro and Linda Carlson’s three parts of mindful practice: attention, intention, and attitude.28

We’re not proposing a new model of communication in this text; we’re proposing a new way of coupling interpersonal communication with mindfulness. So, how would mindful interpersonal communication work? According to Levine Tatkin, “Mindful communication is all about being more conscious about the way you interact with the other person daily. It is about being more present when the other person is communicating to you.” 29 As such, we argue that mindful communication is learning to harness the power of mindfulness to focus our ability to communicate with other people interpersonally effectively.

Many of us engage in mindless communication every day. We don’t pay attention to the conversation; we don’t think about our intentions during the interaction; and we don’t analyze our attitudes while we talk. Have you ever found yourself doing any of the following during an interpersonal interaction?

- Constantly checking your smartphone.

- Focusing on anything but the other person talking.

- Forming your responses before the other person stops talking.

- Cutting the other person off while they are talking.

- Constantly interrupting the other person while they are talking.

- Getting impatient when the other person doesn’t “get to the point fast enough.”

- Trying to come up with solutions the person never asked for.

- Getting bored.

- Having biases against the other person or their ideas without really listening to them.

- Starting arguments for no reason.

- Finding yourself yelling or screaming at someone else.

- Refusing to “give in” or “find the middle ground” when engaged in conflict.

These are just a few examples of what mindless interpersonal interactions can look like when we don’t consider the attention, intention, and attitude. Mindful interpersonal communication, on the other hand, occurs when we engage in the following communication behaviors:30

- Listening to your partner without being distracted.

- Holding a conversation without being too emotional.

- Being non-judgmental when you talk, argue, or even fight with your partner.

- Accepting your partner’s perspective even if it is different from yours.

- Validating yourself and your partner.

The authors of this text truly believe that engaging in mindful interpersonal communicative relationships is very important in our day-to-day lives. All of us are bombarded by messages, and it’s effortless to start treating all messages as if they were equal and must be attended to within a given moment. Let’s look at that first mindless behavior we talked about earlier, checking your cellphone while you’re talking to people. As we discussed in Chapter 1, our minds have a habit of wandering 47% of the time. 31 Our monkey brains are constantly jumping from idea to idea before we add in technology. If you’re continually checking your cellphone while you’re talking to someone, you’re allowing your brain to roam even more than it already does.

Effective interpersonal communication is hard. The goal of a mindful approach to interpersonal communication is to train ourselves to be in the moment with someone listening and talking. We’ll talk more about listening and talking later in this text. For now, we’re going to wrap-up this chapter by looking at some specific skills to enhance your interpersonal communication.

Key Takeaways

- In action models, communication was viewed as a one-directional transmission of information from a source or sender to some destination or receiver. These models include the Shannon and Weaver Model, the Schramm Model and Berlo’s SMCR model.

- Interactional models viewed communication as a two-way process, in which both the sender and the receiver equally share the responsibility for communication effectiveness. Examples of the interactional model are Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson Model and Osgood and Schramm Model.

- The transactional models differ from the interactional models in that the transactional models demonstrate that individuals are often acting as both the sender and receiver simultaneously. An example of a transactional model is Barnlund’s model

Exercises

- Choose one action model, one interactional model, and Barnlund’s transactional model. Use each model to explain one communication scenario that you create. What are the differences in the explanations of each model?

- Choose the communication model with which you most agree. Why is it better than the other models?