2.2: Understanding Cultural Differences

- Page ID

- 110267

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)In this section, we will look at cultural differences through the lenses of German psychologist Geert Hofstede; American anthropologist Edward Hall, and Scottish Business Professor Charles Tidwell. By gaining a rough understanding of different cultures, we can learn what to expect and how to interact with citizens of our diverse, multicultural society.

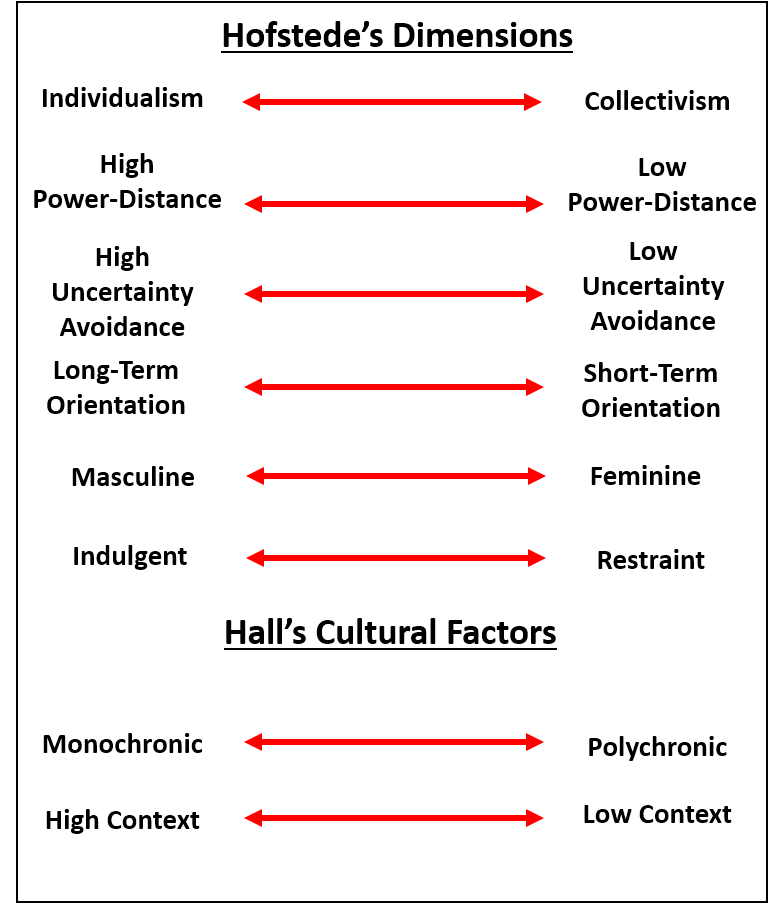

Hofstede's Dimensions of Culture

Psychologist Geert Hofstede published his cultural dimensions model at the end of the 1970s. Since then, it's become an internationally recognized standard for understanding cultural differences. Hofstede studied people who worked for IBM in more than 50 countries and identified six dimensions that could distinguish one culture from another. These six dimensions are individualism vs. collectivism, discussed in the previous section; high power distance vs. low power distance; high certainty avoidance vs. low certainly avoidance; long-term vs. short-term orientation; masculine vs. feminine; and indulgence vs. restraint.

Individualism and Collectivism

Put simply, you can think if an individualistic culture as an I culture where members are able to make choices based on personal preference with little regard for others, except for close family or significant relationships. They can pursue their own wants and needs free from concerns about meeting social expectations. The United States is a highly individualistic culture. While we value the role of certain aspects of collectivism such as government and social organizations, at our core we strongly believe it is up to each person to find and follow his or her path in life.

In a highly collectivistic culture, a we culture, just the opposite is true. It is the role of individuals to fulfill their place in the overall social order. Personal wants and needs are secondary to the needs of society at large. There is immense pressure to adhere to social norms and those who fail to conform risk social isolation, disconnection from family, and perhaps some form of banishment. China is typically considered a highly collectivistic culture. In China, multigenerational homes are common, and tradition calls for the oldest son to care for his parents as they age.

High Power-Distance and Low Power-Distance

Power is a normal feature of any relationship or society. How power is perceived, however, varies among cultures. In high power-distance cultures, the members accept some having more power and some having less power, and accept that this power distribution is natural and normal. Those with power are assumed to deserve it, and likewise, those without power are assumed to be in their proper place. In such a culture, there will be a rigid adherence to the use of titles, “Sir,” “Ma’am,” “Officer,” “Reverend,” and so on. The directives of those with higher power are to be obeyed, with little question.

In low power-distance cultures, the distribution of power is considered far more arbitrary and viewed as a result of luck, money, heritage, or other external variables. Those in power are far more likely to be challenged in a low power-distance culture than they would in a high power-distance culture. A wealthy person is typically seen as more powerful in western cultures. Elected officials, like United States Senators, will be seen as powerful since they had to win their office by receiving majority support. However, individuals who attempt to assert power are often faced with those who stand up to them, question them, ignore them, or otherwise refuse to acknowledge their power. While some titles may be used, they will be used far less than in high power-distance culture. For example, in colleges and universities in the U.S., it is far more common for students to address their instructors on a first-name basis, and engage in casual conversation on personal topics. In contrast, in a high power-distance culture like Japan, the students rise and bow as the teacher enters the room, address them formally at all times, and rarely engage in any personal conversation.

High Uncertainty Avoidance and Low Uncertainty Avoidance

This index shows the degree to which people accept or avoid something that is strange, unexpected, or different from the status quo.

Societies with high uncertainty avoidance choose strict rules, guidelines, and behavior codes. They usually depend on absolute truths or the idea that only one truth decides all proper conduct. High uncertainty avoidance cultures limit change and place a very high value on history, doing things as they have been done in the past, and honoring stable cultural norms.

Low uncertainty avoidance cultures see change is seen as inevitable and normal. These cultures are more accepting of contrasting opinions or beliefs. Society is less strict and lack of certainty is more acceptable. In a low uncertainty avoidance culture, innovation in all areas is valued. Businesses in the U.S. that can change rapidly, innovate quickly, and respond immediately to market and social pressures are seen as far more successful. Even though the U.S. is generally low in uncertainty avoidance, we can see some evidence of a degree of higher uncertainty avoidance related to certain social issues. As society changes, there are many who will decry the changes as they are “forgetting the past,” “dishonoring our forebears,” or “abandoning sacred traditions.” In the controversy over same-sex marriage, the phrase “traditional marriage” is used to refer to a two person, heterosexual marriage, suggesting same-sex marriage is a violation of tradition. Changing social norms creates uncertainty, and for many changes are very unsettling.

Long-Term Orientation and Short-Term Orientation

People and cultures view time in different ways. For some, the “here and now” is paramount, and for others, “saving for a rainy day” is the dominant view.

In a long-term culture, significant emphasis is placed on planning for the future. For example, the savings rates in France and Germany are 2-4 times greater than in the U.S., suggesting cultures with more of a “plan ahead” mentality (Pasquali & Aridas, 2012). These long-term cultures see change and social evolution are normal, integral parts of the human condition.

In a short-term culture, emphasis is placed far more on the “here and now.” Immediate needs and desires are paramount, with longer-term issues left for another day. The U.S. falls more into this type. Legislation tends to be passed to handle immediate problems, and it can be challenging for lawmakers to convince voters of the need to look at issues from a long-term perspective. With the fairly easy access to credit, consumers are encouraged to buy now versus waiting. We see evidence of the need to establish “absolute Truth” in our political arena on issues such as same-sex marriage, abortion, and gun control. Our culture does not tend to favor middle grounds in which truth is not clear-cut.

Masculine and Feminine

Expectations for gender roles are a core component of any culture. All cultures have some sense of what it means to be a “man” or a “woman.” Masculine cultures are traditionally seen as more aggressive and domineering, while feminine cultures are traditionally seen as more nurturing and caring.

In a masculine culture, such as the U.S., winning is highly valued. We respect and honor those who demonstrate power and high degrees of competence. Consider the role of competitive sports such as football, basketball, or baseball, and how the rituals of identifying the best are significant events. The 2017 Super Bowl had 111 million viewers, (Huddleston, 2017) and the World Series regularly receives high ratings, with the final game in 2016 ending at the highest rating in ten years (Perez, 2016).

More feminine societies, such as those in the Scandinavian countries, will certainly have their sporting moments. However, the culture is far more structured to provide aid and support to citizens, focusing their energies on providing a reasonable quality of life for all (Hofstede, 2012b).

Indulgence and Restraint

A more recent addition to Hofstede’s dimensions of culture, the indulgence/restraint continuum addresses the degree of rigidity of social norms of behavior. He states:

Indulgence stands for a society that allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human drives related to enjoying life and having fun. Restraint stands for a society that suppresses gratification of needs and regulates it by means of strict social norms (Hofstede, 2012a).

Indulgent cultures are comfortable with individuals acting on their more basic human drives. Sexual mores are less restrictive, and one can act more spontaneously than in cultures of restraint. Those in indulgent cultures will tend to communicate fewer messages of judgment and evaluation. Every spring thousands of U.S. college students flock to places like Cancun, Mexico, to engage in a week of fairly indulgent behavior. Feeling free from the social expectations of home, many will engage in some intense partying, sexual activity, and fairly limitless behaviors.

Cultures of restraint, such as many Islamic countries, have rigid social expectations of behavior that can be quite narrow. Guidelines on dress, food, drink, and behaviors are rigid and may even be formalized in law. In the U.S., a generally indulgent culture, there are sub-cultures that are more restraint-focused. The Amish are highly restrained by social norms, but so too can be inner-city gangs. Areas of the country, like Utah with its large Mormon culture, or the Deep South with its large evangelical Christian culture, are more restrained than areas such as San Francisco or New York City. Rural areas often have more rigid social norms than do urban areas. Those in more restraint-oriented cultures will identify those not adhering to these norms, placing pressure on them, either openly or subtly, to conform to social expectations.

Hall's Cultural Variations

In addition to these 6 dimensions from Hofstede, anthropologist Edward T. Hall identified two more significant cultural variations (Raimo, 2008).

Monochronic and Polychronic

Another aspect of variations in time orientation is the difference between monochronic and polychronic cultures. This refers to how people perceive and value time.

In a monochronic culture, like the U.S., time is viewed as linear, as a sequential set of finite time units. These units are a commodity, much like money, to be managed and used wisely; once the time is gone, it is gone and cannot be retrieved. Consider the language we use to refer to time: spending time; saving time; budgeting time; making time. These are the same terms and concepts we apply to money; time is a resource to be managed thoughtfully. Since we value time so highly, that means:

- Punctuality is valued. Since “time is money,” if a person runs late, they are wasting the resource.

- Scheduling is valued. Since time is finite, only so much is available, we need to plan how to allocate the resource. Monochronic cultures tend to let the schedule drive activity, much like money dictates what we can and cannot afford to do,

- Handling one task at a time is valued. Since time is finite and seen as a resource, monochronic cultures value fulfilling the time budget by doing what was scheduled. Compare this to a financial budget: funds are allocated for different needs, and we assume those funds should be spent on the item budgeted. In a monochronic culture, since time and money are virtually equivalent, adhering to the “time budget” is valued.

- Being busy is valued. Since time is a resource, we tend to view those who are busy as “making the most of their time;” they are seen as using their resources wisely.

In a polychronic culture, like Spain, time is far, far more fluid. Schedules are more like rough outlines to be followed, altered, or ignored as events warrant. Relationship development is more important, and schedules do not drive activity. Multi-tasking is far more acceptable, as one can move between various tasks as demands change. In polychronic cultures, people make appointments, but there is more latitude for when they are expected to arrive. David's appointment may be at 10:15, but as long as he arrives sometime within the 10 o’clock hour, he is on time.

Consider a monochronic person attempting to do business in a polychronic culture. The monochronic person may expect meetings to start promptly on time, stay focused, and for work to be completed in a regimented manner to meet an established deadline. Yet those in a polychronic culture will not bring those same expectations to the encounter, sowing the seeds for some significant intercultural conflict.

High Context and Low Context

The last variation in culture to consider is whether the culture is high context or low context. To establish a little background, consider how we communicate. When we communicate we use a communication package, consisting of all of our verbal and nonverbal communication. As you have learned, our verbal communication refers to our use of language, and our nonverbal communication refers to all other communication variables: body language, vocal traits, and dress.

In low-context cultures, verbal communication is given primary attention. The assumption is that people will say what they mean relatively directly and clearly. Little will be left for the receiver to interpret or imply. In the U.S. if someone does not want something, we expect them to say, “No.” While we certainly use nonverbal communication variables to get a richer sense of the meaning of the person’s message, we consider what they say to be the core, primary message. Those in a high-context culture find the directness of low-context cultures quite disconcerting, to the point of rudeness.

In high-context cultures, nonverbal communication is as important, if not more important, than verbal communication. How something is said is a significant variable in interpreting what is meant. Messages are often implied and delivered quite subtly. Japan is well known for the reluctance of people to use blunt messages, so they have far more subtle ways to indicate disagreement than a low-context culture. Those in low context cultures find these subtle, implied messages frustrating.

In summary, Hofstede’s Dimensions and Hall’s Cultural Variations give us some tools to use to identify, categorize, and discuss diversity in communication. As we learn to see these differences, we are better equipped to manage inter-cultural encounters, communicate more provisionally, and adapt to cultural variations.

While intended to show only broad cultural differences, these eight variables also can be useful tools to identify variations among individuals within a given culture. We can use them to identify sources of conflict or tension within a given relationship, such as a marriage. For example, Keith tends to be a short-term oriented, indulgent, monochronic person, while his wife tends to be long-term oriented, restrained, and more polychronic. Needless to say, they frequently experience their own personal “culture clashes.”

Tidwell's Insights about Culture and Nonverbal Communication

Dr. Charles Tidwell, professor of Intercultural Business Relations at Andrews University, has spent many years studying and teaching intercultural communication. He provides some valuable insights on cultural differences in dress, movements, gestures, eye contact, touch, and vocalizations. Following are notes published from his graduate course on Interpersonal Communication.

General Appearance and Dress

All cultures are concerned about how they look and make judgments based on looks and dress. Some Americans, for instance, appear almost obsessed with dress and personal attractiveness. But cultural standards on what is attractive in dress and on what constitutes modesty vary greatly. An interesting area to research is how dress is used as a sign of status in different cultures.

Movements and Posture

We send information on attitude toward a person by movements and posture (facing or leaning towards another), emotional states (tapping fingers, jiggling coins), and desire to control the environment (moving towards or away from a person). There are more than 700,000 possible motions we can make — so it is impossible to categorize them all! But just be aware the body movement and position are key ingredients in sending messages. Consider the following actions and note cultural differences:

- Slouching (seen as rude in most Northern European areas)

- Hands in the pocket (disrespectful in Turkey)

- Sitting with legs crossed (offensive in Ghana, Turkey)

- Showing soles of feet. (offensive in Thailand, Saudi Arabia)

- Even in the US, there is a considerable difference in acceptable posture

Gestures

It is impossible to catalog them all. But we need to recognize that an acceptable gesture in one’s own culture may be offensive in another. In addition, the amount of gesturing varies from culture to culture. Some cultures are animated; others are restrained. Restrained cultures often feel animated cultures lack manners and overall restraint. Animated cultures often feel restrained cultures lack emotion or interest. Even simple things like using hands to point and count differ. People in the US point with the index finger; Germany with the little finger; and the Japanese with the entire hand (in fact most Asians consider pointing with the index finger to be rude). In counting with the fingers, Germans use the thumb to indicate the number 1; the middle finger is the symbol for 1 in Indonesia.

Facial Expressions

While many facial expressions such as smiling, crying, or showing anger, sorrow, or disgust are recognized worldwide, the intensity varies from culture to culture. Many Asian cultures suppress facial expressions as much as possible. Many Mediterranean (Latino / Arabic) cultures exaggerate grief or sadness while most American men hide grief or sorrow. Some see “animated” expressions as a sign of a lack of control. Too much smiling is viewed as a sign of shallowness in some cultures. Women smile more than men.

Eye Contact and Gaze

In the USA, eye contact indicates our degree of attention or interest, regulates interaction, communicates emotion, defines power and status, and has a central role in managing the impressions of others. Western cultures see direct eye to eye contact as positive and advise children to look a person in the eyes. But within the USA, differences exist. For example, African-Americans use more eye contact when talking and less when listening with the reverse being true for Anglo-Americans.

- Arabic cultures make prolonged eye contact and believe it shows interest and helps them understand the truthfulness of the other person. (A person who doesn’t reciprocate is seen as untrustworthy)

- Japan, Africa, Latin American, Caribbean — avoid eye contact to show respect.

Touch

Touch is culturally determined! The basic pattern is that cultures with high emotional restraint concepts (English, German, Scandinavian, Chinese, Japanese) have little public touch; those which encourage emotion (Latino, Middle-East, Jewish) accept frequent touches. But each culture has a clear concept of what parts of the body one may not touch. The basic message of touch is to show affection or to control others (i.e. hug, kiss, hit, kick). But rules for touch vary greatly, as shown below:

- Traditional Koreans (and many other Asian countries) don’t touch strangers., especially members of the opposite sex.

- Islamic and Hindu Cultures: typically don’t touch with the left hand. To do so is a social insult. The left hand is for toilet functions. It is mannerly in India to break your bread only with your right hand (sometimes difficult for non-Indians)

- Islamic cultures generally don’t approve of any touching between genders (even handshakes). But consider such touching (including hand-holding, hugs) between same-sex to be appropriate.

- Many Asians don’t touch the head. (The head houses the soul and a touch puts it in jeopardy).

Vocalizations

Vocal characterizers such as a laugh, cry, yell, moan, whine, belch, and yawn send different messages in different cultures. (Japan — giggling indicates embarrassment; India – belch indicates satisfaction) Other vocal qualifiers (volume, pitch, rhythm, tempo, and tone) also vary. Loudness indicates strength in Arabic cultures and softness indicates weakness; indicates confidence and authority to the Germans; indicates impoliteness to the Thais; indicates loss of control to the Japanese. (Generally, one learns not to “shout” in Asia for nearly any reason!). Loudness is gender-based as well: women tend to speak higher and more softly than men.

Key Terms

Topics for Discussion

Although Hofstede's and Hall's Cultural Dimensions are useful in a study of cultures and co-cultures, it is important that we are careful not to oversimplify. Watch The Danger of a Single Story (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg). What were key takeaways from this video?