10.7: Visual Aids

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147055

Learning Objectives

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- explain the rationale for using visual aids.

- identify the characteristics of good slides.

- use slideware appropriately.

Quite commonly, we employ visual aids to assist us in presenting the message in a clear, easily followed manner. Although they are called visual aids, they are any sensory element added to the speech to enhance the speaker's message. Typically, speakers use visual elements, such as graphs and charts, but visual aids can also include items for the audience to hear, touch, taste, or smell.

It is important to understand that visual aids are used to aid the speaker, not to replace the speaker. At all times, the focus of the event should be on the speaker and the verbal message, not on the sensory aids. The speaker needs to smoothly integrate the visual aids into the presentation so as not to distract from the core message of the speech. A general rule of thumb is if the speech cannot be presented without the visual aids, the visual aids are being used too heavily. Visual aids can be forgotten, may not work, or equipment may break down. Struggling to deal with non-functioning visual aids can severely damage the credibility of the speaker, so a good speaker is ready to adapt and move forward, adapting to the challenge of not having the aids.

Purposes of Visual Aids

We use visual aids for four reasons:

- To Clarify: A picture really is worth a thousand words. In many cases, a visual aid can communicate a message more clearly than words. Imagine trying to explain the beauty of a Caribbean Island or the complexity of an automobile engine without the use of a visual element. Words alone will not have the same impact as when combined with an image.

- To Enhance Memory Value: When the audience receives the message in multiple ways, through the speaker's spoken message and through the visual aids, the memory value of the message increases. For some audience members, hearing the message will suffice, but for others, a visual element is more memorable. Using a visual aid allows the audience to tap into the message in a way that works best for them.

- To Fulfill Audience Expectations: With the advent of slideware, such as PowerPoint, audiences have become accustomed to seeing these types of visuals accompanying a presentation. At times, the speaker needs to use a visual aid because the audience expects it. For example, at conferences, it is common that audience members will need a printout of slides to validate attendance, so not using a visual aid becomes a barrier to audience engagement.

- To Add Variety: Although this should not be used as a primary purpose, if the speaker is using a visual aid to clarify or to enhance memory value, the aids also provide some nice variety for the audience. Avoid using aids just for variety, as they can too easily become more important than the message.

Slideware

While PowerPoint, Prezi, and other software options are excellent tools for creating professional, intriguing, and informative visual aids, many of us have experienced horrible slideware presentations in which the speaker talked to the screen, read from the screen, or failed to coordinate what they were saying with what the audience was viewing. By now, students have had enough experience viewing these presentations that most should have an idea of what not to do.

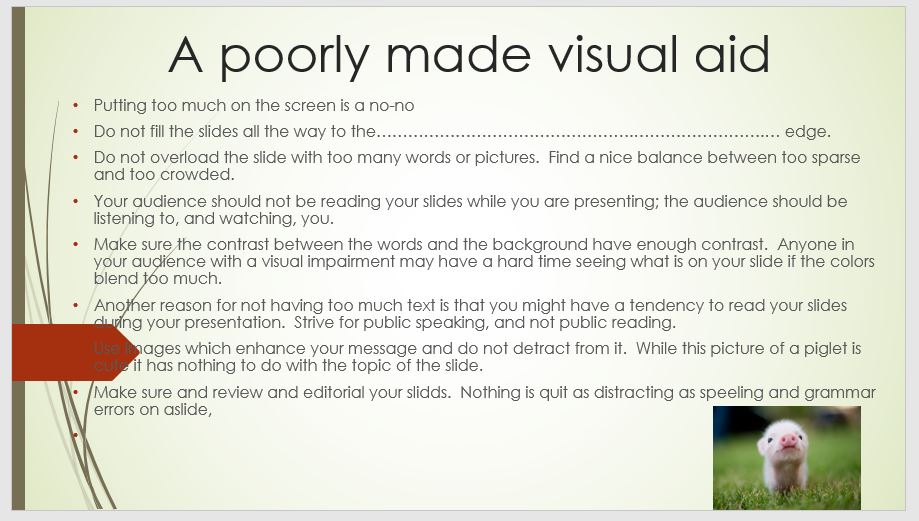

When creating slideware presentations, each slide should be purposeful and thoughtfully created. Each word, bullet point, or image should be on the slide for a distinct reason, not simply as decoration. Good slideware is created with a clear goal in mind.

Creating slides

- Use a consistent theme from slide to slide, keeping colors and fonts the same throughout.

- Use no less than an 18-size font, but do not make them so large they are “yelling” at the audience.

- Avoid the tendency to put too much on the screen. Use keywords or phrases, leaving the speaker to fill in the details.

- Use the transition tools to reveal points one at a time. Whenever a visual aid appears, regardless of what it is, the audience will immediately attempt to decode the whole thing. The speaker should reveal only what they want the audience to focus on at that moment.

- Use only significant images. A significant image is one that is selected to make a specific point, and one the speaker will deliberately draw to the audience’s attention. Images should not be used for background or decoration. Since the audience will look at everything on the screen, the images can be too distracting.

- Do not fill slides to the edge. Leave space to stand slightly overlapping the screen to keep the speaker and the slide as one visual element.

- Do not overload the slide. Find a nice balance between too sparse and too crowded.

- Use black slides or blank slides for when there is nothing to show the audience. Plan them right into the presentation. If using a remote with a blackout option, plan when to use the feature in place of blank/black slides.

- Carefully consider the opening slide. Most people assume a title slide is needed, but many times they are unnecessary distractions. For most speeches, simply start with a black slide and only reveal the content slides as they become relevant to the speech content.

- Do not use any more slides or visual information than necessary but use what is needed. Be thoughtful in deciding what is needed to aid your audience in understanding the point, but at the same time do not use it too much so it distracts from the speaker and the message.

- Always be prepared for the presentation to not work. Technology is prone to failure, so being able to give a presentation without slideware is an important skill. A common situation in professional settings is to provide the audience with a printout of the slides, so while not ideal, in the event of technology failure, the speaker can guide the audience through the printed version of the slideware.

One final caution: slideware can hijack development time away. These are powerful tools allowing the speaker to create detailed animations, special effects, and a plethora of visually energetic and stimulating imagery. The vast majority of these are unnecessary in public speaking, and the speakers can easily find themselves spending hours on an effect that ends up having little value. Instead, work for a minimal, concise, neat slideware presentation, and then put time into practicing with it to create a smooth, unified speech.

Speaking with slideware

Many of us have seen poor slideware presentations. One of the reasons audiences may dread PowerPoint is how poorly the speaker uses it. It is a tool and needs to be handled carefully and appropriately. Using it effectively can enhance the message but using it poorly can make the speech a trying time for the audience.

- First, and most importantly, do not read from the slides. This is one of the most common complaints regarding speakers using slideware. Most of us read fine, and to have the speaker read the slide to us is insulting. While the slide helps us focus on what is being emphasized at that moment, it does not convey the core message; that is the speaker’s job.

- A second major mistake some speakers make is speaking to the screen. While it is good to glance at the screen to make sure the correct slide is being projected and to draw the audience's attention to a specific item, the speaker’s focus must remain on the audience. Always remember, every time the speaker glances at the screen, the audience follows even if there is nothing substantial to look at.

- Control focus. For the audience to take in both the speaker and the screen, if possible, stand next to the screen, creating a unified visual picture. If the speaker wants the audience’s full attention, they should take a step or two away from the screen while displaying a black or blank slide. Do not stand in front of the screen, in the light, or in a manner that blocks the audience’s view.

As mentioned above, use the transitions tools in the slideware to control when specific items appear and disappear, but also use gestures to control the focus by pointing out specific items on the screen. For instance, if Kathryn is describing how horses are judged at a county fair and she has an image of a horse on the screen, she should point to the various parts of the horse as she describes them. It is Kathryn’s job to guide the audience’s focus to the key part of the image. - Use a remote, if possible. A presentation remote gives enormous freedom to move, gesture, and otherwise vary the visual image being presented to the audience. Prior to speaking, it is crucial the speaker is comfortable with how the remote works and can use it quickly and confidently. It is important to know what buttons to use, and equally important, which ones to avoid (and how to recover if a button gets hit). How well the speaker uses the remote and interacts with the slideware influences credibility, so being proficient is important.

- Test prior to speaking. Make very sure the technology works before starting the presentation. Just because something worked at home on a personal laptop does not mean it will work in the presentation venue. Some technical issues to consider:

- Is the speaker expected to provide the laptop? Or will it be sufficient to bring the presentation file to be used on the host’s equipment?

- Is the host system compatible with the specific slideware program used?

- Is there a presentation remote?

- Is sound required? If so, make sure to test before the presentation.

- Is internet access required? If so, is there a password required or other obstacles to getting online? Is the link fast enough for what you need?

- How does the projector work? If connecting to a personal laptop, who provides the cables?

- How far away is the nearest electrical outlet? Is an extension cord needed? Who will provide one?

The best assumption about using technology is something will go wrong, so the norm should be to arrive early, set up, and test thoroughly. Failing to have the technology ready and working is the responsibility of the speaker. Problems may be seen as the speaker being unprepared, hurting their credibility.

Corporate comedian, Don McMillan, identifies some of the pitfalls of PowerPoint:

Using Visual Aids

In addition to the suggestions on using slideware, when using visual aids of any type, three overriding guidelines are:

Even when the visual aid is revealed, use gestures and movement to control the audience's focus more precisely. For example, for a list of items on a chart, the speaker should gesture to draw focus to whichever item they want their audience to focus on.

Always remember, whatever the speaker looks at, the audience looks at. If the speaker keeps making nervous glances at the visual aid, the audience will follow, diverting their focus.

- Control Audience Focus: When a visual aid is revealed, the audience will focus on the visual aid, working to figure out what it is, what it says, and what it means. The speaker should have the aids visible only when they want the audience to pay attention to them. Determine the right time to unveil the visual aid and the right time to put the visual aid away.

- Practice: Being comfortable in the use of visual aids communicates preparation and confidence. Practice with them to get a strong feeling for when and how to manipulate them. If the speaker begins to appear less confident and less sure of what to do with the aids, the audience becomes uncomfortable, anticipating failure versus anticipating success.

- Limit Them: The speaker must carefully consider what is important and what is not. Too many aids shift the focus from the speaker to the aids, the movement of the aids, and the general confusion caused by the amount of movement in the front of the room. Fewer well-developed aids have more impact than using many.

Key Concepts

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Purpose of Visual Aids

- To clarify

- To enhance memory value

- To fulfill audience expectations

- To add variety

Slideware

- Speaking with slideware

Using Visual Aids

- Control audience focus

- Practice

- Limit them