8.1.5: Forgetting

- Page ID

- 92733

Interference vs. Decay

Chances are that you have experienced memory lapses and been frustrated by them. You may have had trouble remembering the definition of a key term on an exam or found yourself unable to recall the name of an actor from one of your favorite TV shows. Maybe you forgot to call your aunt on her birthday or you routinely forget where you put your cell phone.

Oftentimes, the bit of information we are searching for comes back to us, but sometimes it does not. Clearly, forgetting seems to be a natural part of life. Why do we forget? And is forgetting always a bad thing?

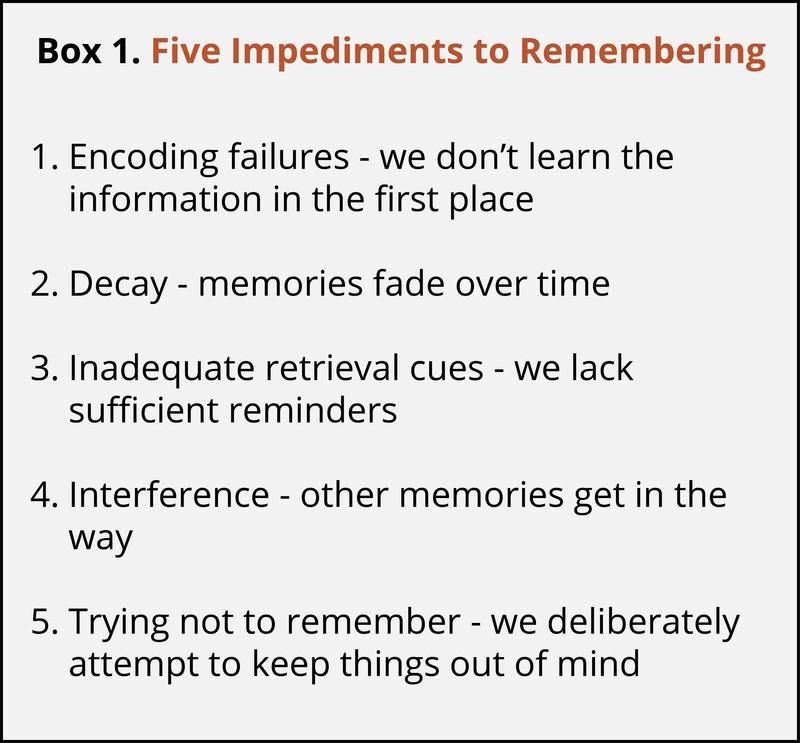

Causes of Forgetting

One very common and obvious reason why you cannot remember a piece of information is because you did not learn it in the first place. If you fail to encode information into memory, you are not going to remember it later on. Usually , encoding failures occur because we are distracted or are not paying attention to specific details. For example, people have a lot of trouble recognizing an actual penny out of a set of drawings of very similar pennies, or lures, even though most of us have had a lifetime of experience handling pennies ( Nickerson & Adams, 1979 ). However, few of us have studied the features of a penny in great detail, and since we have not attended to those details, we fail to recognize them later. Similarly, it has been well documented that distraction during learning impairs later memory (e.g., Craik, Govoni, Naveh-Benjamin, & Anderson, 1996 ). Most of the time this is not problematic, but in certain situations, such as when you are studying for an exam, failures to encode due to distraction can have serious repercussions.

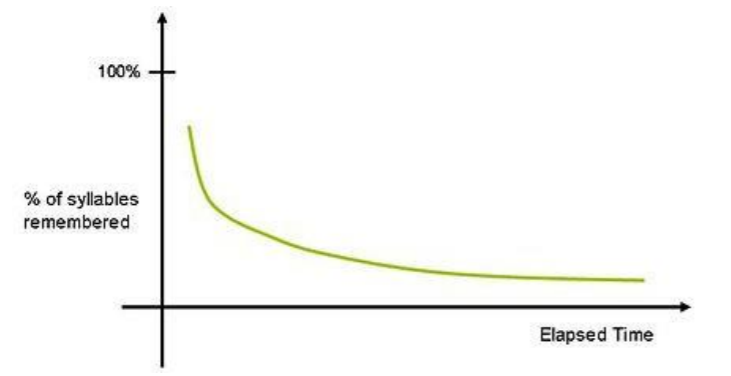

Another proposed reason why we forget is that memories fade, or decay , over time. It has been known since the pioneering work of Hermann Ebbinghaus ( 1885/1913 ) that as time passes, memories get harder to recall. Ebbinghaus created more than 2,000 nonsense syllables, such as dax , bap , and rif , and studied his own memory for them, learning as many as 420 lists of 16 nonsense syllables for one experiment. He found that his memories diminished as time passed, with the most forgetting happening early on after learning. His observations and subsequent research suggested that if we do not rehearse a memory and the neural representation of that memory is not reactivated over a long period of time, the memory representation may disappear entirely or fade to the point where it can no longer be accessed. As you might imagine, it is hard to definitively prove that a memory has decayed as opposed to it being inaccessible for another reason. Critics argued that forgetting must be due to processes other than simply the passage of time, since disuse of a memory does not always guarantee forgetting ( McGeoch, 1932 ). More recently, some memory theorists have proposed that recent memory traces may be degraded or disrupted by new experiences ( Wixted, 2004 ). Memory traces need to be consolidated , or transferred from the hippocampus to more durable representations in the cortex, in order for them to last ( McGaugh, 2000 ). When the consolidation process is interrupted by the encoding of other experiences, the memory trace for the original experience does not get fully developed and thus is forgotten.

Both encoding failures and decay account for more permanent forms of forgetting, in which the memory trace does not exist, but forgetting may also occur when a memory exists yet we temporarily cannot access it. This type of forgetting may occur when we lack the appropriate retrieval cues for bringing the memory to mind. You have probably had the frustrating experience of forgetting your password for an online site. Usually, the password has not been permanently forgotten; instead, you just need the right reminder to remember what it is. For example, if your password was “pizza0525,” and you received the password hints “favorite food” and “Mom’s birthday,” you would easily be able to retrieve it. Retrieval hints can bring back to mind seemingly forgotten memories (Tulving & Pearlstone, 1966). One real- life illustration of the importance of retrieval cues comes from a study showing that whereas people have difficulty recalling the names of high school classmates years after graduation, they are easily able to recognize the names and match them to the appropriate faces (Bahrick, Bahrick, & Wittinger, 1975). The names are powerful enough retrieval cues that they bring back the memories of the faces that went with them. The fact that the presence of the right retrieval cues is critical for remembering adds to the difficulty in proving that a memory is permanently forgotten as opposed to temporarily unavailable.

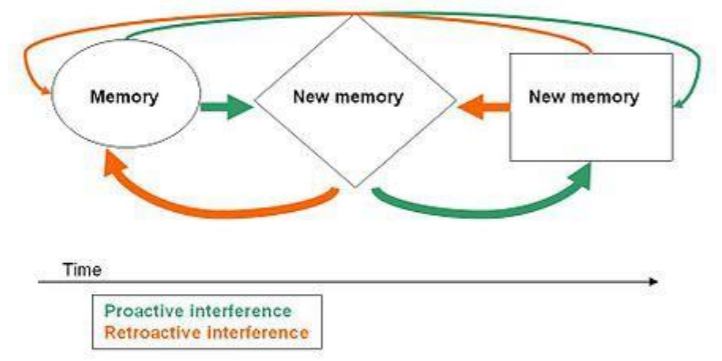

Retrieval failures can also occur because other memories are blocking or getting in the way of recalling the desired memory. This blocking is referred to as interference . For example, you may fail to remember the name of a town you visited with your family on summer vacation because the names of other towns you visited on that trip or on other trips come to mind instead. Those memories then prevent the desired memory from being retrieved. Interference is also relevant to the example of forgetting a password: passwords that we have used for other websites may come to mind and interfere with our ability to retrieve the desired password. Interference can be either proactive, in which old memories block the learning of new related memories, or retroactive, in which new memories block the retrieval of old related memories. For both types of interference, competition between memories seems to be key (Mensink & Raaijmakers, 1988). Your memory for a town you visited on vacation is unlikely to interfere with your ability to remember an Internet password, but it is likely to interfere with your ability to remember a different town’s name. Competition between memories can also lead to forgetting in a different way. Recalling a desired memory in the face of competition may result in the inhibition of related, competing memories (Levy & Anderson, 2002). You may have difficulty recalling the name of Kennebunkport, Maine, because other Maine towns, such as Bar Harbor, Winterport, and Camden, come to mind instead. However, if you are able to recall Kennebunkport despite strong competition from the other towns, this may actually change the competitive landscape, weakening memory for those other towns’ names, leading to forgetting of them instead.

Finally, some memories may be forgotten because we deliberately attempt to keep them out of mind . Over time, by actively trying not to remember an event, we can sometimes successfully keep the undesirable memory from being retrieved either by inhibiting the undesirable memory or generating diversionary thoughts (Anderson & Green, 2001). Imagine that you slipped and fell in your high school cafeteria during lunch time, and everyone at the surrounding tables laughed at you. You would likely wish to avoid thinking about that event and might try to prevent it from coming to mind. One way that you could accomplish this is by thinking of other, more positive, events that are associated with the cafeteria. Eventually, this memory may be suppressed to the point that it would only be retrieved with great difficulty (Hertel & Calcaterra, 2005)

Adaptive Forgetting

We have explored five different causes of forgetting. Together they can account for the day-to- day episodes of forgetting that each of us experience. Typically, we think of these episodes in a negative light and view forgetting as a memory failure. Is forgetting ever good? Most people would reason that forgetting that occurs in response to a deliberate attempt to keep an event out of mind is a good thing. No one wants to be constantly reminded of falling on their face in front of all of their friends. However, beyond that, it can be argued that forgetting is adaptive, allowing us to be efficient and hold onto only the most relevant memories (Bjork, 1989; Anderson & Milson, 1989). Shereshevsky, or “S,” the mnemonist studied by Alexander Luria (1968), was a man who almost never forgot. His memory appeared to be virtually limitless. He could memorize a table of 50 numbers in under 3 minutes and recall the numbers in rows, columns, or diagonals with ease. He could recall lists of words and passages that he had memorized over a decade before. Yet Shereshevsky found it difficult to function in his everyday life because he was constantly distracted by a flood of details and associations that sprung to mind. His case history suggests that remembering everything is not always a good thing. You may occasionally have trouble remembering where you parked your car but imagine if every time you had to find your car, every single former parking space came to mind. The task would become impossibly difficult to sort through all of those irrelevant memories. Thus, forgetting is adaptive in that it makes us more efficient. The price of that efficiency is those moments when our memories seem to fail us (Schacter, 1999).

The Fallibility of Memory

Memories can be encoded poorly or fade with time; the storage and recovery process is not flawless.

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish among the factors that make some memories unrecoverable

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Memories are affected by how a person internalizes eventsthrough perceptions, interpretations, and emotions.

- Transience refers to the general deterioration of a specific memory over time.

- Transience is caused by proactive and retroactive interference.

- Encoding is the process of converting sensory input into a formthat memory is capable of processing and storing.

- Memories that are encoded poorly or shallowly may not be recoverable.

Key Terms

- transience: The deterioration of a specific memory over time.

Memory is not perfect. Storing a memory and retrieving it later involves both biological and psychological processes, and the relationship between the two is not fully understood. Memories are affected by how a person internalizes events through perceptions, interpretations, and emotions. This can cause a divergence between what is internalized as a memory and what actually happened in reality; it can also cause events to encode incorrectly, or not at all.

Transience

It is easier to remember recent events than those further in the past, and the more we repeat or use information, the more likely it is to enter into long-term memory. However, without use, or with the addition of new memories, old memories can decay. “Transience” refers to the general deterioration of a specific memory over time. Transience is caused by proactive and retroactive interference. Proactive interference is when old information inhibits the ability to remember new information, such as when outdated scientific facts interfere with the ability to remember updated facts. Retroactive interference is when new information inhibits the ability to remember old information, such as when hearing recent news figures, then trying to remember earlier facts and figures.

Encoding Failure

Encoding is the process of converting sensory input into a form able to be processed and stored in the memory. However, this process can be impacted by a number of factors, and how well information is encoded affects how well it is able to be recalled later. Memory is associative by nature; commonalities between points of information not only reinforce old memories, but serve to ease the establishment of new ones. The way memories are encoded is personal; it depends on what information an individual considers to be relevant and useful, and how it relates to the individual’s vision of reality. All of these factors impact how memories are prioritized and how accessible they will be when they are stored in long-term memory. Information that is considered less relevant or less useful will be harder to recall than memories that are deemed valuable and important. Memories that are encoded poorly or shallowly may not be recoverable at all.

Types of Forgetting

There are many ways in which a memory might fail to be retrieved, or be forgotten.

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate among the different processes involved in forgetting

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The trace decay theory of forgetting states that all memories fade automatically as a function of time; under this theory, you need to follow a certain path, or trace, to recall a memory.

- Under interference theory, all memories interfere with the ability to recall other memories.

- Proactive interference occurs when memories from someone’s past influence new memories; retroactive interference occurs when old memories are changed by new ones, sometimes so much that the original memory is forgotten.

- Cue-dependent forgetting, also known as retrieval failure, is the failure to recall information in the absence of memory cues.

- The tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon is the failure to retrieve a wordfrom memory, combined with partial recall and the feeling that retrieval is imminent.

Key Terms

- Trace decay theory: The theory that if memories are not reviewedor recalled consistently, they will begin to decay and will ultimately be forgotten.

- Retroactive interference: When newly learned information interferes with and impedes the recall of previously learned information.

- Proactive interference: When past memories inhibit an individual’sfull potential to retain new memories.

- Trace: A pathway to recall a memory.

Memory is not static. How you remember an event depends on a large number of variables, including everything from how much sleep you got the night before to how happy you were during the event. Memory is not always perfectly reliable, because it is influenced not only by the actual events it records, but also by other knowledge, experiences, expectations, interpretations, perceptions, and emotions. And memories are not necessarily permanent: they can disappear over time. This process is called forgetting. But why do we forget? The answer is currently unknown. There are several theories that address why we forget memories and information over time, including trace decay theory, interference theory, and cue-dependent forgetting.

Trace Decay Theory

The trace decay theory of forgetting states that all memories fade automatically as a function of time. Under this theory, you need to follow a certain pathway, or trace, to recall a memory. If this pathway goes unused for some amount of time, the memory decays, which leads to difficulty recalling, or the inability to recall, the memory. Rehearsal, or mentally going over a memory, can slow this process. But disuse of a trace will lead to memory decay, which will ultimately cause retrieval failure. This process begins almost immediately if the information is not used: for example, sometimes we forget a person’s name even though we have just met them.

Interference Theory

It is easier to remember recent events than those further in the past. ” Transience ” refers to the general deterioration of a specific memory over time. Under interference theory, transience occurs because all memories interfere with the ability to recall other memories. Proactive and retroactive interference can impact how well we are able to recall a memory, and sometimes cause us to forget things permanently.

Proactive Interference

Proactive interference occurs when old memories hinder the ability to make new memories. In this type of interference, old information inhibits the ability to remember new information, such as when outdated scientific facts interfere with the ability to remember updated facts. This often occurs when memories are learned in similar contexts, or regarding similar things. It’s when we have preconceived notions about situations and events, and apply them to current situations and events. An example would be growing up being taught that Pluto is a planet in our solar system, then being told as an adult that Pluto is no longer considered a planet. Having such a strong memory would negatively impact the recall of the new information, and when asked how many planets there are, someone who grew up thinking of Pluto as a planet might say nine instead of eight.

Retroactive Interference

Retroactive interference occurs when old memories are changed by new ones, sometimes so much that the original memory is forgotten. This is when newly learned information interferes with and impedes the recall of previously learned information. The ability to recall previously learned information is greatly reduced if that information is not utilized, and there is substantial new information being presented. This often occurs when hearing recent news figures, then trying to remember earlier facts and figures. An example of this would be learning a new way to make a paper airplane, and then being unable to remember the way you used to make them.

Cue-Dependent Forgetting

When we store a memory, we not only record all sensory data, we also store our mood and emotional state. Our current mood thus will affect the memories that are most effortlessly available to us, such that when we are in a good mood, we recollect good memories, and when we are in a bad mood, we recollect bad ones. This suggests that we are sometimes cued to remember certain things by, for example, our emotional state or our environment. Cue-dependent forgetting, also known as retrieval failure, is the failure to recall information in the absence of memory cues. There are three types of cues that can stop this type of forgetting:

- Semantic cues are used when a memory is retrieved because of its association with another memory. For example, someone forgets everything about his trip to Ohio until he is reminded that he visited a certain friend there, and that cue causes him to recollect many more events of the trip.

- State-dependent cues are governed by the state of mind at the time of encoding. The emotional or mental state of the person (such as being inebriated, drugged, upset, anxious, or happy) is key to establishing cues. Under cue-dependent forgetting theory, a memory might be forgotten until a person is in the same state.

- Context-dependent cues depend on the environment and situation. Memoryretrieval can be facilitated or triggered by replication of the context in which the memory was encoded. Such conditions can include weather, company, location, the smell of a particular odor, hearing a certain song, or even tasting a specific flavor.

Other Types of Forgetting

Trace decay, interference, and lack of cues are not the only ways that memories can fail to be retrieved. Memory’s complex interactions with sensation, perception, and attention sometimes render certain memories irretrievable.

Absentmindedness

If you’ve ever put down your keys when you entered your house and then couldn’t find them later, you have experienced absentmindedness. Attention and memory are closely related, and absentmindedness involves problems at the point where attention and memory interface. Common errors of this type include misplacing objects or forgetting appointments. Absentmindedness occurs because at the time of encoding, sufficient attention was not paid to what would later need to be recalled.

Blocking

Occasionally, a person will experience a specific type of retrieval failure called blocking. Blocking is when the brain tries to retrieve or encode information, but another memory interferes with it. Blocking is a primary cause of the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon. This is the failure to retrieve a word from memory, combined with partial recall and the feeling that retrieval is imminent. People who experience this can often recall one or more features of the target word, such as the first letter, words that sound similar, or words that have a similar meaning. Sometimes a hint can help them remember: another example of cued memory.