8.1.7: Reconstruction of Memories

- Page ID

- 92735

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Memories are not stored as exact replicas of reality; rather, they are modified and reconstructed during recall.

Learning Objectives

- Evaluate how mood, suggestion, and imagination can lead to memory errors or bias

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Because memories are reconstructed, they are susceptible to being manipulated with false information.

- Much research has shown that the phrasing of questions can alter memories. Children are particularly suggestible to such leading questions.

- People tend to place past events into existing representations of the world ( schemas ) to make memories more coherent.

- Intrusion errors occur when information that is related to the theme of a certain memory, but was not actually a part of the original episode, become associated with the event.

- There are many types of bias that influence recall, including fading- affect bias, hindsight bias, illusory correlation, self-serving bias, self- reference effect, source amnesia, source confusion, mood-dependent memory retrieval, and the mood congruence effect.

Key Terms

- Consolidation: The act or process of turning short-term memories into more permanent, long-term memories.

- Schema: A worldview or representation.

- Leading question: A query that suggests the answer or contains the information the examiner is looking for.

Memory Errors

Memories are fallible. They are reconstructions of reality filtered through people’s minds, not perfect snapshots of events. Because memories are reconstructed, they are susceptible to being manipulated with false information. Memory errors occur when memories are recalled incorrectly; a memory gap is the complete loss of a memory.

Schemas

In a 1932 study, Frederic Bartlett demonstrated how telling and retelling a story distorted information recall. He told participants a complicated Native American story and had them repeat it over a series of intervals. With each repetition, the stories were altered. Even when participants recalled accurate information, they filled in gaps with false information. Bartlett attributed this tendency to the use of schemas . A schema is a generalization formed in the mind based on experience. People tend to place past events into existing representations of the world to make memories more coherent. Instead of remembering precise details about commonplace occurrences, people use schemas to create frameworks for typical experiences, which shape their expectations and memories. The common use of schemas suggests that memories are not identical reproductions of experience, but a combination of actual events and already-existing schemas. Likewise, the brain has the tendency to fill in blanks and inconsistencies in a memory by making use of the imagination and similarities with other memories.

Leading Questions

Much research has shown that the phrasing of questions can also alter memories. A leading question is a question that suggests the answer or contains the information the examiner is looking for. For instance, one study showed that simply changing one word in a question could alter participants’ answers: After viewing video footage of a car accident, participants who were asked how “slow” the car was going gave lower speed estimations than those who were asked how “fast” it was going. Children are particularly suggestible to such leading questions.

Intrusion Errors

Intrusion errors occur when information that is related to the theme of a certain memory, but was not actually a part of the original episode, become associated with the event. This makes it difficult to distinguish which elements are in fact part of the original memory. Intrusion errors are frequently studied through word-list recall tests.

Intrusion errors can be divided into two categories. The first are known as extra-list errors, which occur when incorrect and non-related items are recalled, and were not part of the word study list. These types of intrusion errors often follow what are known as the DRM Paradigm effects, in which the incorrectly recalled items are often thematically related to the study list one is attempting to recall from. Another pattern for extra-list intrusions would be an acoustic similarity pattern, which states that targets that have a similar sound to non-targets may be replaced with those non-targets in recall. The second type of intrusion errors are known as intra-list errors, which consist of irrelevant recall for items that were on the word study list. Although these two categories of intrusion errors are based on word-list studies in laboratories, the concepts can be extrapolated to real-life situations. Also, the same three factors that play a critical role in correct recall (i.e., recency, temporal association, and semantic relatedness) play a role in intrusions as well.

Types of Memory Bias

A person’s motivations, intentions, mood, and biases can impact what they remember about an event. There are many identified types of bias that influence people’s memories.

Fading-Affect Bias

In this type of bias, the emotion associated with unpleasant memories “fades” (i.e., is recalled less easily or is even forgotten) more quickly than emotion associated with positive memories.

Hindsight Bias

Hindsight bias is the “I knew it all along!” effect. In this type of bias, remembered events will seem predictable, even if at the time of encoding they were a complete surprise.

Illusory Correlation

When you experience illusory correlation, you inaccurately assume a relationship between two events related purely by coincidence. This type of bias comes from the human tendency to see cause-and-effect relationships when there are none; remember, correlation does not imply causation.

Mood Congruence Effect

The mood congruence effect is the tendency of individuals to retrieve information more easily when it has the same emotional content as their current emotional state. For instance, being in a depressed mood increases the tendency to remember negative events.

Mood-State Dependent Retrieval

Another documented phenomenon is mood-state dependent retrieval, which is a type of context-dependent memory. The retrieval of information is more effective when the emotional state at the time of retrieval is similar to the emotional state at the time of encoding. Thus, the probability of remembering an event can be enhanced by evoking the emotional state experienced during its initial processing.

Salience Effect

This effect, also known as the Von Restorff effect, is when an item that sticks out more (i.e., is noticeably different from its surroundings) is more likely to be remembered than other items. Self-Reference Effect

In the self-reference effect, memories that are encoded with relation to the self are better recalled than similar memories encoded otherwise.

Self-Serving Bias

When remembering an event, individuals will often perceive themselves as being responsible for desirable outcomes, but not responsible for undesirable ones. This is known as the self- serving bias.

Source Amnesia

Source amnesia is the inability to remember where, when, or how previously learned information was acquired, while retaining the factual knowledge. Source amnesia is part of ordinary forgetting, but can also be a memory disorder. People suffering from source amnesia can also get confused about the exact content of what is remembered.

Source Confusion

Source confusion, in contrast, is not remembering the source of a memory correctly, such as personally witnessing an event versus actually only having been told about it. An example of this would be remembering the details of having been through an event, while in reality, you had seen the event depicted on television.

Considerations for Eyewitness Testimony

Increasing evidence shows that memories and individual perceptions are unreliable, biased, and manipulable.

Learning Objectives

- Analyze ways that the fallibility of memory can influence eyewitness testimonies

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The other-race effect is a studied effect in which eyewitnesses are not as good at facially identifying individuals from races different from their own.

- The weapon-focus effect is the tendency of an individual to hyper-focus on a weapon during a violent or potentially violent crime; this leads to encoding issues with other aspects of the event.

- The time between the perception and recollection of an event can also affect recollection. The accuracy of eyewitness memory degrades rapidly after initial encoding; the longer the delay between encoding and recall, the worse the recall will be.

- Research has consistently shown that even very subtle changes in the wording of a question can influence memory. Questions whose wording might bias the responder toward one answer over another are referred to as leadingquestions.

- Age has been shown to impact the accuracy of memory; younger witnesses are more suggestible and are more easily swayed by leading questions and misinformation.

- Other factors, such as personal biases, poor visibility, and the emotional tone of the event can influence eyewitness testimony.

Key Terms

- Leading question: A question that suggests the answer or contains the information the examiner is looking for.

- Eyewitness: Someone who sees an event and can report or testify about it.

Eyewitness testimony has been considered a credible source in the past, but its reliability has recently come into question. Research and evidence have shown that memories and individual perceptions are unreliable, often biased, and can be manipulated.

Encoding Issues

Nobody plans to witness a crime; it is not a controlled situation. There are many types of biases and attentional limitations that make it difficult to encode memories during a stressful event.

Time

When witnessing an incident, information about the event is entered into memory. However, the accuracy of this initial information acquisition can be influenced by a number of factors. One factor is the duration of the event being witnessed. In an experiment conducted by Clifford and Richards (1977), participants were instructed to approach police officers and engage in conversation for either 15 or 30 seconds. The experimenter then asked the police officer to recall details of the person to whom they had been speaking (e.g., height, hair color, facial hair, etc.). The results of the study showed that police had significantly more accurate recall of the 30-second conversation group than they did of the 15-second group. This suggests that recall is better for longer events.

Other-Race Effect

The other-race effect (a.k.a., the own-race bias, cross-race effect, other-ethnicity effect, samerace advantage) is one factor thought to affect the accuracy of facial recognition. Studies investigating this effect have shown that a person is better able to recognize faces that match their own race but are less reliable at identifying other races, thus inhibiting encoding. Perception may affect the immediate encoding of these unreliable notions due to prejudices, which can influence the speed of processing and classification of racially ambiguous targets. The ambiguity in eyewitness memory of facial recognition can be attributed to the divergent strategies that are used when under the influence of racial bias.

Weapon-Focus Effect

The weapon-focus effect suggests that the presence of a weapon narrows a person’s attention, thus affecting eyewitness memory. A person focuses on a central detail (e.g., a knife) and loses focus on the peripheral details (e.g. the perpetrator’s characteristics). While the weapon is remembered clearly, the memories of the other details of the scene suffer. This effect occurs because remembering additional items would require visual attention, which is occupied by the weapon. Therefore, these additional stimuli are frequently not processed.

Retrieval Issues

Trials may take many weeks and require an eyewitness to recall and describe an event many times. These conditions are not ideal for perfect recall; memories can be affected by a number of variables.

More Time Issues

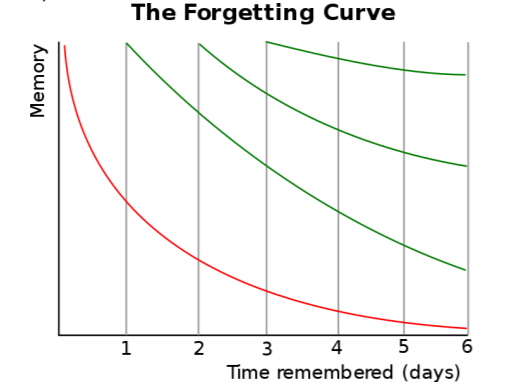

The accuracy of eyewitness memory degrades swiftly after initial encoding. The “forgetting curve” of eyewitness memory shows that memory begins to drop off sharply within 20 minutes following initial encoding, and begins to level off around the second day at a dramatically reduced level of accuracy. Unsurprisingly, research has consistently found that the longer the gap between witnessing and recalling the incident, the less accurately that memory will be recalled. There have been numerous experiments that support this claim. Malpass and Devine (1981) compared the accuracy of witness identifications after 3 days (short retention period) and 5 months (long retention period). The study found no false identifications after the 3-day period, but after 5 months, 35% of identifications were false.

The forgetting curve of memory: The red line shows that eyewitness memory declines rapidly following initial encoding and flattens out after around 2 days at a dramatically reduced level of accuracy.

Leading Questions

In a legal context, the retrieval of information is usually elicited through different types of questioning. A great deal of research has investigated the impact of types of questioning on eyewitness memory, and studies have consistently shown that even very subtle changes in the wording of a question can have an influence. One classic study was conducted in 1974 by Elizabeth Loftus, a notable researcher on the accuracy of memory. In this experiment, participants watched a film of a car accident and were asked to estimate the speed the cars were going when they “contacted” or “smashed” each other. Results showed that just changing this one word influenced the speeds participants estimated: The group that was asked the speed when the cars “contacted” each other gave an average estimate of 31.8 miles per hour, whereas the average speed in the “smashed” condition was 40.8 miles per hour. Age has been shown to impact the accuracy of memory as well. Younger witnesses, especially children, are more susceptible to leading questions and misinformation.

Bias

There are also a number of biases that can alter the accuracy of memory. For instance, racial and gender biases may play into what and how people remember. Likewise, factors that interfere with a witness’s ability to get a clear view of the event—like time of day, weather, and poor eyesight—can all lead to false recollections. Finally, the emotional tone of the event can have an impact: for instance, if the event was traumatic, exciting, or just physiologically activating, it will increase adrenaline and other neurochemicals that can damage the accuracy of memory recall.

Memory Conformity

“Memory conformity,” also known as social contagion of memory, refers to a situation in which one person’s report of a memory influences another person’s report of that same experience. This interference often occurs when individuals discuss what they saw or experienced, and can result in the memories of those involved being influenced by the report of another person. Some factors that contribute to memory conformity are age (the elderly and children are more likely to have memory distortions due to memory conformity) and confidence (individuals are more likely to conform their memories to others if they are not certain about what they remember).