3.5: Child Rearing Practices and Guidance

- Page ID

- 133741

The Elements of Rearing and Guiding Children

So far in this chapter we have looked at theories and ideas that guide our knowledge about the variety of ways in which we think about rearing children. Some of those ideas are quite outdated and yet they seem to remain in the social lexicon when it comes to understanding about what is best for children in their formative years. There is nothing more complicated than raising children as they don't come with an instruction manual. The diversity of ideas we have explored thus far are as diverse as the individual children that are reared in the diversity of families as it relates to their culture and societal constructs.

Child-rearing and Guidance

Parents and caregivers have a responsibility to guide and promote positive socialization strategies for children in their care. These activities are known as discipline or guidance-two words that are often used interchangeably in parenting education. Discipline is defined as “ongoing teaching and nurturing that facilitates self-control, self-direction, competence, and care for others”. It is recommended that caregivers utilize a comprehensive disciplinary approach for guiding children’s behaviors.

Caregivers proactively teach children how to regulate their own behaviors by using age- and developmentally—appropriate strategies that enhance:

- positive, supportive, and nurturing caregiver-child relationships,

- safety, permanency, and consistency,

- acceptable behavioral patterns by removing reinforcements to eliminate undesired behaviors and providing positive reinforcements to strengthen desired behaviors, and

- cognitive, socio emotional, and executive functioning skills.*

For optimal outcomes, all of the above components must consistently function well in an individualized manner for each child, and within the context of children, feeling loved, safe, and secure. Recommended child-rearing strategies are outlined in upcoming pages.

Examples of caregivers’ guidance by stage:

- Newborns: recognize and respond flexibly to infant’s needs while providing generally structured daily routines.

- Infants and toddlers: use limitations, protection, and structure to create safe spaces for play and exploration.

- Early childhood: utilize creative and individualized strategies to guide children’s desirable behavior patterns to become their “typical interactions”.

- School-age: increase children’s own responsibility for self-control via the integration of previously-developed internalized rules of conduct.

- Adolescence: change strategies to foster more autonomy, self-regulation, and responsibility while guiding teens’ safety and positive decision-making skills.

Active Listening

Active listening is a type of communication strategy between two or more people that consists of paying attention to what someone is saying and attempting to understand what is being said. Clinical research studies demonstrate that active listening can be a catalyst in one’s personal growth. For example, children are more likely to listen to themselves if someone else allows them to speak and successfully convey their message.

Learning how to actively listen takes time, practice, and full commitment. Once achieved, it can build a strong foundation for positive communication resulting in a strong caregiver-child relationship by building trust throughout the lifespan. This strategy also tends to improve the quality of conversations by connecting with others on a deeper level, which can lead to more positive and healthy relationships.

How to use this method:

- Caregivers should be on the child’s level and listen in an attentive, nonjudgmental, non-interrupting manner.

- Listeners should pay close attention to possible hidden messages and meanings contained in the verbal communication and should note all non-verbal communication from the child.

- It is important to remember that you are not giving your opinion and thoughts regarding what the child relays to you; you are paraphrasing what the child said and expressing back to the child the emotions the child conveyed.

- Active listening is paying attention and attempting to understand what someone else is saying.

- It is important to note hidden messages in verbal and non-verbal communications.

- It is important to refrain from giving opinions while paraphrasing what the other person is saying.

Anticipatory structure

Anticipatory structure is a strategy where caregivers share plans and provide forewarnings to children regarding upcoming transitions between activities. This can help establish routines and facilitate more smooth changes in routines. It also allows time for children to prepare for changes, which can heighten their cooperation when the change happens. Anticipatory structure is most effective when caregivers provide multiple forewarnings before transitions, give reasoning for what the child is being asked to do, and use age-appropriate language that the child can understand. It is helpful for parents to provide praise or compliments for their children as they follow each step and meet the end goal.

Example

A parent tells their children that it is almost time to go to bed and they have ten minutes to finish playing and then they need to put their toys away. Later the parent reminds the children again and tells them that they have five minutes left to play and then they need to have all of their toys put away. After five minutes, the parent makes sure the children’s toys are put away and asks them to get ready for bed by reminding them of their regular bedtime routine.

- Anticipatory structure provides forewarnings to changes in activities and can help establish routines and cooperation.

CALM

The CALM method is a technique for parents to use to communicate with their children, whether that be talking through a conflict or just sharing about what happened that day. The goal of this method is to give children a voice and help them feel heard. The “best-practice” way to utilize this method would be to implement it every time your child wants to have a conversation one-on-one with you.

- Connect

- Affect

- Listen

- Mirroring

How to use this method:

CONNECT. The first step in the CALM method is connecting with the child. This means putting aside any and all distractions in order to give your full and undivided attention to what the child says to you.

AFFECT. The second step is affect, which is emotion. This means you want to share and show your emotions and feelings with your children and let them know that you have the same emotions as they do. Through this, they can see that you understand and empathize with what they are going through or telling you.

LISTEN. The third step is listening to the child by repeating what is said back to you or asking for clarifications to help the child feel listened to and heard.

MIRRORING. The fourth and final step is mirroring. This is when you (a) make sure you fully understand what the child is telling you, (b) clear up any questions or misunderstandings by paraphrasing (back to child) what the child said and (c) sharing in your child's thoughts and feelings.

Example

Your daughter, Sammie, came to you upset because she didn’t win a contest at school. First, you would connect by removing all of your distractions (putting away phone, stopping what you are doing), turning your attention to her, and making eye contact with her. Next, you would show how her actions affected you by having an upset look on your face and tone in your voice to show you understand her emotions. After this, you would listen to what she tells you and then clarify details to show Deidre you are invested in the conversation. Lastly, you would mirror the interaction back to Deidre by paraphrasing what she told you to show you care about her thoughts and feelings.

By using this technique, children will be able to see and feel that you are listening, caring, and involved in what they are telling you. You want them to feel that they can come to you and trust you about anything going on in their life, big or small.

Constructive Choices

Constructive choices are a child-rearing strategy where parents provide the child with options for the child when making decisions. This allows children to be involved in making choices in their everyday activities, while still maintaining choices that are positive and safe. This strategy can help children learn how to make decisions, and it teaches and guides children about how to analyze their decision-making abilities so they can eventually make decisions on their own.

- How to use this method:

- Limit the number of times you give a child a choice,

- Limit the number of choices you give a child (two to four choices work well),

- Provide developmentally-appropriate choices that keep the child safe and healthy,

- Support the child’s decision, and

- Help children think about their choices and the reasoning behind making each decision.

Example

A caregiver may give a child a choice to keep playing with their toys inside or to clean up the toys and go play outside. When the child decides which one they would like to do, you support their decision. This means helping them to critically think about their choices in the decision making process. The older the child, the more choices can be given.

- Caregivers provide specific options to help guide children’s activities and decision-making abilities.

Four Pluses and a Wish

Four Pluses and a Wish is a parenting strategy aimed at creating cooperation and motivation for children to comply with parental requests. Along with leading to better behavior outcomes, it also works to foster healthy communication and is a good example of parental supportive speech. Four Pluses and a Wish involves the parent providing three pluses, which are positive actions toward their child, before making a request. This helps the child feel more respected by their parents and therefore more likely to comply with parental wishes and requests. There are four steps to follow for this strategy.

How to use this method:

Plus 1

Smile: The parent approaches the child with a smile and a happy facial expression to show the child that nothing is wrong.

Plus 2

Relaxed body language: The parent displays a relaxed body and uses a friendly voice to communicate friendliness and acceptance toward the child.

Plus 3

Say the child’s name: For children, hearing a parent say their name feels more personal, is affirming, and helps make them feel included and respected in the communication.

Plus 4

Compliment the child: Make a positive comment on something the child is doing, wearing, etc., to make the child feel appreciated.

The Wish

Make the request: After providing four pluses for the child, the parent can then make a request (the wish).

Example

Luke is playing with blocks and his mother comes into the room.

Luke’s mother: “Luke, it’s almost time for dinner, please clean up your toys and wash your hands.”

Luke: “I don’t want to clean up yet. I want to keep playing.”

Luke’s mother smiles at Luke and with relaxed body language, kneels to his level. “Luke, that is a great car you built with your blocks, you did a good job building it. Could you put it away for a while and come wash your hands for dinner, please?”

Luke smiled and complied with his mother’s request.

- Three positive actions are made towards the child before making a request.

- This method promotes cooperation and compliance with requests.

I-messages

I-messages are effective communication techniques to use when talking with another person. The goals of I-messages are to keep interactions positive, and avoid blame, guilt, judgment, and shame. I-messages express your own feelings, while “you” messages place assumptions or judgments onto the person with whom you are speaking. A “you” message would sound like, “You need to pay more attention!” or “You shouldn’t be acting like that.”

Here is an example of turning a “you” message into an I-message. The “you” message might be something like, “You always disobey our rules and do whatever you want!” However, turning it into an I-message might sound more like this, “I feel angry when you disobey the rules we’ve laid out for you because I feel disrespected. I like it when you obey the rules, guidelines, and boundaries we have in this family because it makes me feel like you care about me, yourself, and the whole family.”

How to use this method:

- “I feel ___

- When ___

- Because ___

- I like ___”

This outline expresses how you feel about a given situation, action, or behavior by explaining what you feel, why you feel that way, and what you would like the desired behavior to be.

Example

•“I feel worried and anxious when it is one hour past the time you were to be home and I have not heard from you because I fear something bad has happened. I like it when you keep in touch with me if you might be late. I need you to contact me if you will be late.”

- I-messages start with the word “I,” express your own feelings to keep communication positive, and help avoid blame and judgment onto the other person.

Induction

Induction can be used to help youth develop empathy, guide their behaviors, take ownership of their actions, learn acceptable behaviors, and understand how their actions may impact themselves (self-centered induction) and others (other-oriented induction).

How to use this method:

When you have a child’s full attention:

- Explain how one’s actions can affect themselves and others (positively and negatively).

- Use a child’s actions as an example to discuss and recommend expectations for acceptable behavior.

- Model desired behaviors for a child to imitate.

- Use others’ actions as examples to discuss and assess how behaviors can impact others’ feelings.

- Encourage, discuss, and reward desired behaviors.

- Explain and discourage undesirable actions.

- Be consistent and proactive by communicating expectations, discussing outcomes, and identifying feelings related to behaviors on an ongoing basis.

Children reared in an environment that uses this approach tend to have higher moral reasoning, internalized standards for behaviors, prosocial skills, and resistance to external influences when compared to their peers who have not been exposed to this technique.

Example

If a child is taking a sibling’s toys, a caregiver can explain, “When you take your brother’s toys, it causes him to feel sad and that you do not like him. How might you feel if your friend took your bike out of our yard without asking you?”

- Induction is used to help children understand how their behaviors affect themselves and others, take ownership of their actions, and guide them to engage in acceptable behaviors.

Natural and Logical Consequences

In the previous section, Dreikurs was mentioned as he elevated this concept of natural and logical consequences. Caregivers can use both natural and logical consequences for children to learn behaviors that provide better outcomes. Both natural and logical consequences encourage children to take responsibility for their actions and behaviors, but in different ways. Natural consequences allow children to learn from the natural outcomes of a situation and logical consequences allow the parent to set the consequences of a child’s undesired actions or behaviors. Logical consequences work best when consequences are immediate and consistent. It is also important to talk with the child about the behavior and to discuss what alternative behaviors would be better to use.

Examples

- Natural consequence: Sophie leaves her favorite hair styling doll outside overnight. It rains on Sophie’s doll and ruins its hair. Now Sophie’s doll is ruined and she is no longer able to style the doll’s hair.

- Logical consequence: Juan hits a baseball into his neighbor’s yard and breaks the neighbor’s window. Juan’s parents require Juan to apologize to the neighbor and to complete chores around their own home in order to pay for the neighbor’s broken window.

- Natural consequences are when a child learns from and experiences the natural outcomes of situations.

- Logical consequences are when parents set the consequences of a child’s behaviors.

- This works best when the consequences are immediate and consistent.

No-lose Method

This is a democratic approach that results in caregivers and children resolving conflict in a manner in which all parties are satisfied with the solution.

How to use this method:

- Define: All parties communicate their perspectives of the “problem”.

- Brainstorm Solutions: All parties list all possible solutions to resolve the issue.

- Assess Solutions: All parties decide and discuss how they feel about all of the solutions.

- Best Solution: All parties decide upon and agree to implement the best solution.

- Plan in Action: All parties put the best solution into practice.

- Follow-Up: Adult(s) proactively discuss the problem and solution with the child(ren) to revisit the situation

Example

- Define: The “problem” is that siblings are fighting over a book.

- Brainstorm Solutions: The children can take turns reading the book; each child can read a different book; both children can read with each other at the same time with that book; a parent can remove the book so both children need to find different books.

- Assess Solutions: Both children want to read the book together.

- Best Solution: The children and parent agree that the children will read the book together as long as the children do not fight. If they fight while reading the book, the parent will remove the book and both children will need to take a break.

- Plan in Action: The children read the book together and do not fight.

- Follow-Up: Later that same day, the parent asks if they both enjoyed reading that book together. Both children agreed it was an enjoyable time. The parent praised them for not fighting and for solving the issue.

- This method is used to resolve conflict where every party involved discusses their perspective on the problem and possible solutions.

- A solution that satisfies all parties is decided and agreed upon.

Problem Ownership

Problem ownership is an important tool to utilize when caregivers are communicating with children because it can help avoid blaming and arguing. This is when caregivers take time to reflect on an issue and think, “Whose problem is this? Who is actually upset about this?” Sometimes we may think the child is the one with the problem when actually we are the ones getting upset. In reality, the child is just fine – we are the ones that have a problem. This is when a caregiver should own the problem.

If a caregiver owns the problem, it is a perfect opportunity to utilize effective communication strategies such as I-Messages to express one’s thoughts and feelings regarding the problem. If, however, the child owns the problem, caregivers can use this as a chance to practice adult-child interaction techniques such as active listening and the CALM method to connect with the child concerning the problem.

Problem ownership helps caregivers determine which problems they need to figure out themselves, and which problems they should allow their children to figure out. This provides a learning experience to gain responsibility for one’s actions that can be utilized in other relationships as well.

Example

Third-grader tells his dad, “Caleb is not my friend anymore!”

Dad: (active listening) “So, I hear that you are upset. What happened?”

Third-grader: “Caleb knocked down our entire snow fort during recess today! It took us three entire recesses to build it!”

(Dad feels sad for his son and wants to advocate for his son. Dad contemplates calling the teacher or Caleb’s parents. After reflecting, Dad asks himself, “Whose problem is this? It’s my son who is upset. I need to help him navigate this and let him know he can talk to me about these types of issues.” Dad decides to ask open-ended questions and use active listening to learn more about the entire situation.)

Dad: Why don’t you tell me what happened.

Third-grader: Well… (child has the opportunity to retell the incident and decide for himself, with his dad’s nurturing and understanding support, what to do about the problem).

This type of interaction allows a parent to provide support while assisting the child with ways to resolve or work through a problem.

- Problem ownership is when an issue is reflected upon and analyzed to determine who is upset and who owns the problem in a situation.

- A solution can be determined based on who owns the problem.

Positive Language

The manner in which parents communicate with their child can largely determine the child’s own communication methods and language development and can affect the child’s vocabulary and speaking skills over time. Using positive language can greatly support and encourage the child as they get older.

How to use this method:

- Respond quickly and kindly to a child’s needs.

- Provide a listening ear or advice even at inconvenient times.

- Be responsive and consistent.

- Use positive and encouraging words when speaking with a child.

- Set a good example of how to talk to other people in public as well as at home by using manners and respect, such as saying “please,” “thank you,” and “I’m sorry.”

- Avoid sarcasm or ill-willed teasing.

- Use positive, communicative forms of guidance and avoid any form of violent discipline such as spanking.

- Spend time alone with each child, even at a young age. Quality time coupled with open communication encourages the child to feel safe and comfortable with their parents and creates a reliable relationship.

Examples

- Peter and Dan’s mother says, “Thank you for picking up your toys” after they put away the toys in their playroom.

- Kaila returns home from school and says that she has had a bad day at school. Kaila’s dad asks her what had made it a bad day and listens to Kaila explain what had happened.

- Using phrases such as, “I’m sorry,” “please,” “thank you”, and “I love you” often for children of all ages are recommended!

Redirecting

Verbal and physical redirection help promote desirable behaviors by directing children’s attention to a different activity, toy, or behavior. These strategies help teach appropriate behavior, prevent injuries, reduce punishments, remove children from situations, and promote learning and exploration. The goal is to provide children with easy-to-understand alternative actions (verbally and/or physically) instead of using threats, punishments, or telling children what not to do.

How to Use Verbal and Physical Redirection

- Maintain eye contact and come down to the child’s level. Let children know that the act they are performing is unacceptable by using a firm, nurturing voice.

- Explain why the behavior is unacceptable in a clear, consistent, developmentally appropriate manner. This will help children associate these words with the undesirable action.

- Encourage children to practice the desired outcome immediately. For example, instead of telling children not to stand on chairs, verbally explain that they need to sit down while gently touching them to help them sit down carefully.

- Use physical and verbal redirection to foster children’s curiosity. For instance, encourage them to participate in desired acts that they will undoubtedly want to join.

- Provide positive reinforcement and praise for completing the act in a desirable manner.

Verbal redirection is effective without physical redirection, but physical redirection is not effective without verbal redirection. As in most forms of child rearing, communication is a pivotal component of effective parenting strategies. Physical redirection tends to be more effective with younger children because they are still developing their language comprehension. As children develop additional cognitive and language skills, physical redirection should be used less frequently and verbal redirection should be used more often. An extremely important part of effective physical redirection is adding a gentle, nurturing touch simultaneously with the verbal redirection.

| Redirection technique | Incorrect usage | Correct usage |

|---|---|---|

| Verbal redirection | 1. “Stop running in the kitchen, you’ll split your head open!” 2. “I like your jacket, but don’t leave it laying on the ground.” 3. “Stop standing on the chair, you are going to get hurt!” |

1. “The kitchen is not a place to run, walk when you are in here, please.” 2. “I like your jacket, please hang it up after you take it off.” 3. “We do not stand on chairs. Let’s go outside and play in your tree house.” |

| Physical redirection | 1. Grab the child’s arm to make him stop running. 2. Throw the child’s jacket at her after she leaves it laying on the chair. 3. “Stop standing on the chair, you are going to get hurt!” |

1. “The kitchen is not a place to run, please walk when you are in here,” while gently touching the child’s arm to slow him down to a walking pace. 2. “I like your jacket, please hang it up when you take it off.” Gently touch the child’s arm to guide her to the jacket and then to the coat hook. 3. “We do not stand on chairs, we sit on them,” while gently and immediately, touching the child’s leg and arm to help her get to a seated position. |

- Verbal redirection should always include explanations of the correct action that a child can understand while using a gentle, nurturing voice.

- Avoid using threats and telling children what not to do.

- Physical redirection should always be used in combination with verbal redirection.

- Consistent language is key for effective redirection so children associate the same words with undesirable actions.

- It is important to use the same steps and words if children repeat the same behavior. Consistency is key when reinforcing positive behaviors and deterring negative behaviors.

Reward-oriented Parenting and Positive Reinforcement

There are many ways to increase the likelihood of children exhibiting desirable behaviors by using positive reinforcements and rewards. You may want to revisit the information regarding Skinner in the previous section to effectively use this parenting strategy.

Parents or teachers may wish to reinforce children for:

Listening attentively;

- Using appropriate manners (e.g., saying “please,” “you are welcome,” and “thank you”);

- Moving and talking in a manner appropriate for the environment (e.g., using “library voices;” “walking feet”);

- Playing nicely;

- Completing tasks without reminders; and

- Calling or texting if they will be late.

Examples of rewards and positive reinforcements include:

- Complimenting a child’s behavior (e.g., “I really like the way you put all of your clothes away in your room”);

- Praising a child’s actions (e.g., “I am proud of how hard you studied for your spelling quiz.”);

- Giving additional privileges;

- Clapping or cheering;

- Thanking them for behaving a certain way (e.g., “Thank you very much for asking such a detailed question;” “I really appreciate you using your inside voice while we were at the museum.”);

- Making sure they overhear you telling someone else about their positive behavior;

- Smiling at them; and

- Giving tangible rewards (e.g., stickers, incentives).

In order for these methods to be effective, rewards or incentives must:

- be important or valuable to the child,

- occur immediately after the desired behavior, and

- consistently be implemented.

While this is a popular method that is often used in schools, a word of caution is important. Over rewarding children can become a problem if their only motivation to do something is to obtain a reward. Rewards can be both extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic rewards are what is highlighted in this section - something that is outside of the child. Intrinsic rewards are those that motivate from within. Doing something because it is right for you and/or it feels good for you. There needs to be a balance so children do not become overly dependent on the extrinsic reward to shape their behavior.

Examples

Here is a common example of (unintentionally and positively) rewarding inappropriate behavior: An aunt provides candy to her nephew every time he throws a tantrum in the store because he wants candy at the checkout lane. The aunt reinforces the poor behavior (e.g., a tantrum) by providing reinforcers (e.g., candy and attention) every time he throws a tantrum at the grocery store.

Here is an example of positively rewarding the same child to stop the tantrums: Now that this child throws a tantrum with his parents when they go to the grocery store, his parents provide their son with candy only when he does not throw a tantrum in the store. His parents reinforce the appropriate behavior (e.g., not throwing a tantrum) by providing reinforcers (e.g., candy and attention) every time they go to the grocery store and he refrains from throwing a tantrum.

Another way to help the child refrain from throwing a tantrum is to remind the child how we behave in the store. When you are in the store, letting them know that they are behaving appropriately by smiling at them to convey your approval creates a sense of acceptance from the caregiver to the child.

Structure (with Flexibility): Routines, Rules, Directions

Children (and most people of all ages) thrive in flexibly-structured environments. For children, the sense of knowing what to expect typically elicits feelings of safety and security. Caregivers can help children reduce feelings of chaos by providing flexible, but consistent:

- Routines,

- Rules, and

- Concrete, explicit directions with easy-to-understand expectations.

Rules and Routines

In order to maintain consistent routines (e.g., bedtimes, traditions) and rules (e.g., not eating food in certain areas of the house, curfews, wearing a helmet while riding a bicycle) it is important to facilitate and adhere to them as much as possible. Expectations should be developmentally-appropriate and communicated in a manner that can be easily understood.

For instance, perhaps family meals are at 6:30 p.m. because this is the time that everyone gets home from work and school activities. This expectation and all moderations should be communicated with all members on a daily basis but also remain flexible. Exceptions that may change a family mealtime might include attending a school-related activity or having a large family gathering every Sunday at 1:30 p.m.

Directions

Specific, warm, concrete, understandable directions and expectations can improve behaviors, prevent dangerous circumstances, reduce caregivers’ frustrations, and foster children’s learning of appropriate behaviors. It is most effective to tell children exactly what behaviors you desire.

Examples

- “Please use your walking feet while we are in the library,” is more detailed than saying, “Stop that!”

- “We must hold hands in the parking lot to avoid getting hit by a car,” instead of “Hey, come back here!” as the child runs through the parking lot.

Research shows that children’s abilities to anticipate change, use appropriate behaviors, and develop independence are fostered by warm, safe, stable, nurturing, caring, compassionate caregiving on a consistent basis! This means that routines, rules, directions, expectations, and consequences should be responded to or applied every time in a nurturing, warm, consistent manner.

- Providing a warm, close, nurturing, and openly-communicative environment with consistent routines, directions, and rules with reasonable flexibility are key for eliciting feelings of predictability and security.

- It is not too late to learn, teach, and reinforce these skills for caregivers and youth. However, it may take time and practice to elicit changes.

Time-ins and Time-outs

Time-ins are a positive child guidance strategy in which the caregiver stays with the child until they are both calm and can communicate about the issue at hand. When using a time-in the caregiver should stay with the child, and listen to the child and what they are feeling. Once the child has calmed down then the caregiver and child can discuss the child’s behavior and what needs to be changed. Time-ins allow for children to not feel threatened and learn in a positive way. The caregiver and child are able to connect reducing power struggles since everyone’s feelings and needs are considered.

A more common and somewhat opposite approach is the use of time-outs. Time-outs are a less positive approach and can be less effective compared to time-ins. Time-outs are where a child is left to sit alone somewhere away from the caregiver for a set amount of time. To learn about time-outs, such as how and when to use them, visit the cdc’s parent essentials site.

Example

Both time-ins and time-outs are used to:

- stop undesirable behavior,

- help children learn better coping skills, and

- give parents and children a chance to calm down.

- Threats and punishments (e.g., time-outs) are often less effective than positive parenting strategies (e.g., time-ins) for changing behaviors.

- Not all children respond well to time-outs.

- Time-ins can reduce power struggles and calm brains.

Parenting programs that offer guidance strategies for families

Conscious Discipline

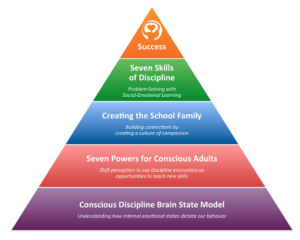

Conscious Discipline is a comprehensive, evidence-based, trauma-informed approach. The founder Becky Bailey, has successfully implemented this program in many early learning environments throughout the nation as well as providing training opportunities for families. It is based on four components, which are scientifically and practically designed for success. Below is an infographic that illustrates those four components:

Brain State Model

Brain State Model

The first component of conscious discipline empowers us to be conscious of brain-body states in ourselves and children. It then provides us with the practical skills we need to manage our thoughts, feeling and actions.

With this ability to self-regulate, we are then able to teach children to do the same. By doing this, we help children who are physically aggressive (survival state) or verbally aggressive (emotional state) become more integrated so they can learn and use problem-solving skills (executive state). When we understand the brain state model, we can clearly see the importance of building our homes, schools and businesses on the core principles of safety, connection and problem-solving.

- The only way to soothe the survival state if through the creation of safety.

- The only way to soothe an upset emotional state is through the creation of connection

- The executive state if the optimal state of problem-solving and learning.

In a survival state where we feel triggered by threat, these skills are flight, fight or surrender. We can’t think clearly when a tiger is chasing us. In the modern world, the tiger may be a disrespectful child, but our brain’s evolutionary skill set is the same: fight, flight or surrender.

Our emotional state is our response to upset – and can only be soothed through connection. An upset emotional state is triggered by the world not going our way. It limits our ability to see from another’s point of view. This upset, unconscious state keeps us on autopilot so our words and tone match those of key authority figures from our childhood. We revert to disciplining the same ways we were disciplined, even if we know these behaviors to be ineffective or hurtful.

Executive State is the optimal state for problem-solving and learning. As we learn to regulate and integrate our internal state to be one of relaxed alertness, we are able access our own brilliance. We are empowered to change and make wise choices. An integrated executive state frees us from past conditioning, attunes us to the feelings and experiences of others, enables us to remain focused enough to set and achieve goals, and allows us to consciously respond instead of automatically react to life events.

Conscious Discipline empowers us to be conscious of brain-body states in ourselves and children. It then provides us with the practical skills we need to manage our thoughts, feeling and actions. With this ability to self-regulate, we are able to teach children to do the same. By doing this, we help children who are physically aggressive (survival state) or verbally aggressive (emotional state) become more integrated so they can learn and use problem-solving skills (executive state). When we understand the brain state model, we can clearly see the importance of building our homes, schools and businesses on the core principles of safety, connection and problem-solving.

As we move up the pyramid (refer to infographic) the second component is seven powers for conscious adults that are necessary in effectively and successfully helping to guide children's behavior.

| Powers | Big idea | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Power of perception | No one can make you angry without your permission. | To teach adults and children to take responsibility for their own upset. |

| Power of unity | We are all in this together. | To perceive compassionately, and offer compassion to others and to ourselves. |

| Power of attention | Whatever we focus on, we get more of. | To create images of expected behavior in a child's brain. |

| Power of free will | The only person you can change is you. | Learning to connect and guide instead of force and coerce. |

| Power of acceptance | The moment is as it is. | To learn to respond to what life offers instead of attempting to make the world go our way. |

| Power of love | Choose to see the best in others. | Seeing the best in others keeps us in the higher centers of our brain so we can consciously respond instead of unconsciously react to life events. |

| Power of intention | Mistakes are opportunities to learn. | To teach a new skill rather than punishing others for lacking skills we think they should possess now. |

The third component is essential in creating school family connections. We know that creating partnerships with families, build trust and mutual respect. We are a team working together with families to provide an environment that is supportive and empowering.

The school family is built on a healthy family model with the goal of optimal develop of all members. This includes:

Willingness to learn - without willingness, each interaction becomes a power struggle instead of a learning opportunity. The School Family brings all children and adults, especially the most difficult, to a place of willingness through a sense of belonging.

Impulse Control - connection with others wires the brain for impulse control. Disconnected children are disruptive and prone to aggressive, shutting down, or bullying behaviors. The School Family uses connection to encourage impulse control while teaching self-regulation skills in context.

Attention - our attentional system is sensitive to stress and becomes engaged with positive emotions. The School Family reduces stress while creating an atmosphere of caring, encouragement and meaningful contributions.

The last and fourth component are the seven skills of discipline. They include the following:

- Composure - anger management, delay of gratification

- Encouragement - prosocial skills, kindness, caring, helpfulness

- Assertiveness - bully prevention, healthy boundaries

- Choices - impulse control, goal achievement

- Empathy - emotional regulation, perspective taking

- Positive intent - cooperation, problem solving

- Consequences - learning from your mistakes

To find out more about this program you can visit the website where there is more information and resources regarding Conscious Discipline.

Love and Logic Parenting

Love and Logic Parenting was founded by Jim Fay and Foster Cline. They saw that families needed strategies to help deal with the problems their children were having. The principles in this program were formulated to help families to develop strategies that would bring the fun back into parenting. Over the years the program has been updated and this is the most current program developed in 2012.

The six techniques that are taught in the course:

- Putting an end to arguing, back talk, and begging

- Teaching responsibility without losing their love

- Setting limits without waging war

- Avoiding power-struggles

- Guiding kids to own and solve their problems

- Teaching kids to complete chores without reminders and without pay

This parenting program is usually taught in a cohort that involves 6 2-hour sessions. The workbook that comes with the program states the following.

Through this program, you will learn techniques that:

- Are simple and easy to learn.

- Teach responsibility and character.

- Lower your stress level.

- Have immediate and positive effects.

- Up the odds that you will enjoy livelong positive relationships with your kids and your grandchildren.

Active Parenting

Active parenting was founded in 1980 and was the first video-based parenting education program. The need for such an innovation in parenting education was based on two beliefs about parenting in our democratic society:

- Parenting well is extremely important.

- Parenting well is extremely difficult.

This training program is designed to teach a method of parenting and problem solving that will help families prepare children to courageously meet the challenges life poses. And it helps to build relationships that bring joy and satisfaction for a lifetime. The core beliefs of this parenting program is that parenting is the most important job you will ever do in our society. It is based on a six week training model where you will:

- Realize or recall mistakes you have made in the past in your own parenting. Everyone does and it is important to recognize those mistakes, but it is far more important to let go so that you can develop new strategies that will provide better outcomes for you and your children.

- Realize that you will make further mistakes as you learn new skills. Mistakes are a part of the learning process. When trying on new strategies, you are apt to make mistakes and there is no value in punishing yourself. The value comes in recognizing that you are not perfect and that you are open to learning and trying new strategies.

That six week training model includes the following content:

- the active parent

- winning cooperation

- responsibility and discipline

- understanding and redirecting behavior

- building courage, character, and self-esteem

- the active family now

Systematic Training for Effective Parenting (S.T.E.P.)

This parenting program was founded by a group of psychologists who believed that families needed support and strategies to create healthier ways of parenting. The philosophy of this parent program is to provide:

- a look at long-term goals of parenting

- information on how young children think, feel, and act

- skills that can increase your enjoyment and effectiveness as a parent

- skills that can develop your child's self-esteem and confidence

- support for yourself as a parent and as a person

- effective ways to teach cooperation and discipline

The course covers the following areas:

- Understanding young children - how they grow and develop

- Understanding young children's behavior

- Building self-esteem in the early years

- Learning and talking to young children

- Helping young children learn to cooperate

- Young children's social and emotional development

While this may seem like a comprehensive, exhaustive look at the varying parenting strategies, they are many more as well as more that keep surfacing. This shows us that effective parenting is an important aspect for both families and teachers who work with their children. It is important to note that parenting is based on many aspects and we need to be culturally responsive to other ways of parenting.

Recently, the Brazelton Touchpoints Center has created a program called: Parenting While Black. They offer many webinars with professionals on subjects that are relevant for raising black children. This program began in 2020 and since then they have had many webinars to support Black families in raising their Black children. Here are a few of the webinar titles:

- Standing in our Black Joy and Excellence with our Children, Families, and Communities

- Black Mental Health Matters: Being Black in White Spaces

- Elevating our Racial Identity: Flourishing in Blackness Across the Life Span

- Infertility, Fertility, and Birthing People: The Black Experience

- Thriving in the Midst: Grounding and Uplifting Our Babies, Children, Families, and Communities

- Literacy, Technology, and Art: Healing the Harm and Centering Our Joy in Raising Black Infants, Children and Youth

You can visit the Brazelton Touchpoints website for more information.

References

"Parenting and Family Diversity" by Diana Lang is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Parenting the Love and Logic Way: Workbook, Charles Fay, PhD and Jim Fay, 2012

For more information about positive parenting strategies by ages and stages, visit the CDC website