5.8: Interrelationships of Families, School and Communities

- Page ID

- 134996

The Importance of Home/School Connection

Prior to Covid-19, home and school for children who may have not been homeschooled were a young child's two most important worlds. Children and families had to bridge these two worlds every day. It is important that home and school are connected in positive, respectful ways in which children feel secure. But when the two worlds are at odds because of apathy, lack of understanding, or an inability to work together, children suffer. Teachers who truly value the family's role in a child's education, and recognize how much they can accomplish by working with families, can build a true partnership. This section 5.8 will help you by addressing the following topics:

- Getting to know families

- Making families feel welcome

- Communicating with families

- Partnering with families on children's learning

- Responding to challenging situations

Appreciating Differences

Just as you get to know each child and use what you learn to develop a relationship that helps every child learn, you begin building a partnership with families by getting to know and appreciate each family. Every family is different. Teachers must vary the ways in which they communicate and involve families to reach every family. Think about the structure of your family did you live in a house with multiple generations? Families vary in regards to personalities and temperament with different comfort levels in relating to their child's school. Our life experiences, including the level of education, socio-economic status, immigrant status, may impact how families engage with their child's school and teacher. It's also important to acknowledge that we all have cultural differences and different beliefs, values, and practices. What are your personal experiences with schools and teachers? In what ways in understanding your experiences can assist in appreciating how families engage with their child's school? Knowing and appreciating what is unique or different about each family helps you to build relationships and support children's learning and development.

Belonging

Initial contacts with children's families are opportunities to get to know them better and understand their experiences, values, and beliefs. Some programs start with enrollment at the school, others use home visits. I can remember my daughter's teacher sending postcards to each student welcoming the family as a whole to the next grade, this made me feel as if the teacher cared and took the time to develop a relationship with not only the student but also the family. Families who feel welcome in the classroom are more likely to return and become involved in the program. When children first enter your program, their parents are likely to be especially interested in finding out what their child will be learning and what each day will be like. You can be prepared to meet this interest by making available as many of the following as possible:

- Take families and children on a tour of the classroom, introducing the inside and outside classroom environments. This can also be virtually or a video in which you and teachers tour not only the classroom but also the school. This may be helpful in decreasing anxiety and apprehension about what to expect and assist families in talking with their children about their school and classroom.

- Hold an open house to allow families to meet each other and experience the classroom environment.

- Create a display at the entrance to your classroom with pictures and descriptions of life in your classroom based on the languages of your children and families as well as the community. (Adapted from National PTA Family Guide)

Communication

Communication with families is a means of building and maintaining relationships. What is the influence of culture on communication styles? One thing we learned from living in a Pandemic is the use of technology. Schools provided technology to children as we pivoted to a remote learning environment and still may utilize this as schools are opening and temporarily shutting down for the well-being and health and safety of the teachers, staff, and children. Some schools might be using platforms to maintain open dialogue and communication with families. It is important to communicate in ways that meet the needs and ability levels of family members, particularly those whose primary language is not English.

Understanding the History

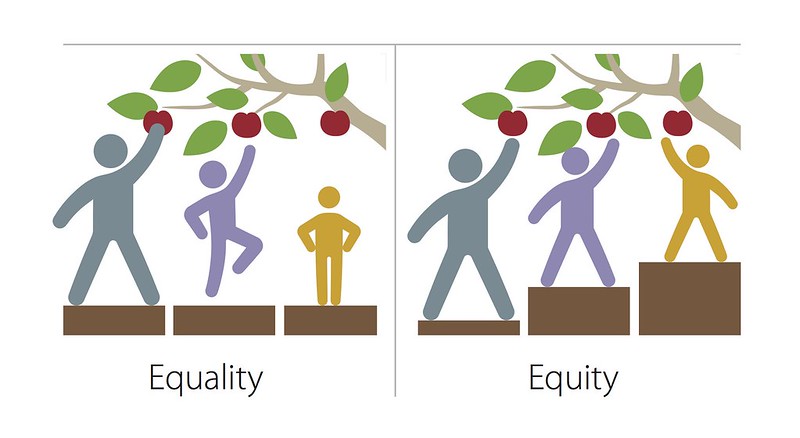

Schools and systems and policies which support schools can lend to how educators/teachers build relationships with families and support the needs of the community in which they are housed. For example, when we begin to look at policies and laws that changed schools structures it allows us to understand the difference between equality and equity. Equality is providing the same opportunity to all. Equity is meeting the specific needs of the individual to partake in the opportunity being provided.

Policies and Laws

Mendez vs. Westminister (1947)

Just after the end of World War II, Sylvia Mendez was eight years old and a student at a racially segregated elementary school in Westminster, California. She wanted to attend a nearby school, but it was reserved for white-only students. Her parents (along with four other Mexican-American families) sued the school district on behalf of the community's 5,000 Latino and Latina students. In 1946, the plaintiffs won their case in federal court, making it the first time in U.S. history that a school district was told it had to desegregate.

The Mendez case had enormous implications for civil rights in the country. It preceded the Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision by eight years. Future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall represented both Sylvia Mendez and later Linda Brown in the Brown v. Board of Education case. He used some of the same arguments from the Mendez case to win the Brown decision.

In the Mendez v. Westminster case, the judge wrote these words challenging the "separate but equal" doctrine established in the Plessy v. Ferguson case in 1898:

"The equal protection of the laws’ pertaining to the public school system in California is not provided by furnishing in separate schools the same technical facilities, textbooks and courses of instruction to children of Mexican ancestry that are available to the other public school children regardless of their ancestry. A paramount requisite in the American system of public education is social equality. It must be open to all children by unified school association regardless of lineage."

A national hero, Sylvia Mendez received a 2010 Presidential Medal of Freedom and in 2018 was awarded the National Hispanic Hero Award. She continues to work for equality and justice for Latinos and all people of color.

The Maestas Desegregation Case

A 1914 case, Francisco Maestas et al. v. George H. Shone, et al., is a little-known forerunner to Sylvia Mendez and her family's fight to end educational segregation of Mexican American children. The case involved a railroad worker, Francisco Maestas, who was unable to enroll his son in the Alamosa, Colorado public school nearest their home. School officials demanded the boy attend a "Mexican school" with the district's other children of Mexican descent because it was assumed the children needed to learn English - even though most of the children at the school spoke English. The district court judge ruled in favor of the Maestas family, stating that all English-speaking children should be allowed to attend the school closest to their homes. Efforts are under way to build a memorial to the case as a milestone in ending segregation of Mexican children based on language and race ("The Most Important School Desegregation Case You've Never Heard Of", National Education Policy Newsletter, July 9, 2020).

Brown vs Board of Education

Jim Crow laws began around 1965 following the ratification of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery in the United States. Jim Crow required separate accommodations for Whites and blacks. And then in 1896, with the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, the “separate but equal” law became constitutional. Since these laws were built on the notion of white supremacy and black inferiority, “separate but equal” is indeed a misnomer. In 1954, the Brown v. Board of Education unanimous decision overturned Plessy and decided that separate is inherently unequal. But it was not until 1968 that the Supreme Court ordered segregated school systems dismantled.

Individual Disability Education Act (IDEA)

Developmental Disabilities are a group of disabilities, including ADHD, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Cerebral Palsy, Intellectual Disabilities, Hearing Loss, Learning Disability, Vision Impairments, and delays. These occur before age 21 and are expected to last throughout the lifetime.

Intellectual disabilities are disabilities that occur before age 21 – during a person’s developmental stage of life – and are likely to be lifelong. A person with a developmental disability may require support in learning (both academic and experiential learning), judgment and reasoning. Some people with intellectual disabilities can live independently, work, and have families, while some need maximum support in all aspects of daily living.

Common developmental disabilities include Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, intellectual or cognitive disability, learning disability, vision impairment, or neurological impairments.

Intellectual or cognitive disabilities require some specialized assistance in learning. There is a wide range of people who have this diagnosis, so we can’t assume anything just because a person has a label of intellectual disability. Most people with intellectual disabilities are able to acquire information and skills in order to live independently and work as adults. A small percentage, however, need lifelong maximum support in activities of daily living like eating, showering, and dressing.

There are many causes of intellectual disability, including genetic disorders, falls, malnutrition, environmental pollution, birth trauma, infections, child abuse and accidents.

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) are very common – according to the Centers for Disease Control from 2017, 1 in 59 children has been diagnosed with ASD. The criteria for a diagnosis of ASD are complicated.

While ASD is sometimes characterized as a communication disorder, increasingly, some people believe autism is simply a different way of seeing the world, and the behaviors that accompany autism should be viewed as a form of diversity rather than something that needs professional intervention. It’s important to remember that everyone with the diagnosis of ASD is an individual and nothing can be assumed about her or his abilities or need for support simply because of the diagnosis. Not every autistic person has every trait named in the diagnostic criteria, or experiences the same characteristic in the same way. While there is a growing movement of autistic pride, each autistic person experiences autism in their own way, and each may require different types of support for housing, education, employment, relationships, communication, healthcare, and activities of daily living.

Learning Disabilities are very common and can be thought of as a processing disorder, where information is process a bit differently than with people who don’t have this disability. One way to accommodate children and adults with learning disabilities is to provide extra time to process information or to express ideas. Dyslexia (difficulty in reading), dysgraphia (difficulty in writing), and dyscalculia (difficulty with arithmetic), are common learning disabilities. Another common learning disability is attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) which results in difficulty in sustaining focus.

Cerebral Palsy is a very common developmental disability that causes people to experience stiff muscles or difficulties with coordination that causes a jerky motion. In some people it causes a continuous writhing motion. Some people with cerebral palsy can walk, while others need to use a wheelchair for mobility. A small percentage of cerebral palsy is inherited, but most cerebral palsy is caused by birth trauma or another kind of trauma, such as an accident.

Some people with cerebral palsy have cognitive or learning disabilities, while many do not. So like having a diagnosis of any other disability, having a diagnosis of cerebral palsy doesn’t imply anything about intelligence, judgment or ability to work.

Epilepsy is a seizure disorder, where neurons in the brain can cause several different types of seizures. Some seizures are minor and the individual experiencing them loses contact with the environment for a brief period of time. Some seizures might cause a person to have repetitive motions for a minute or more. And some seizures are more involved and cause the person experiencing them to lose control of muscles for a period of time.

Neurological impairments are a collection of conditions resulting from issues with the nervous system that may cause a range of symptoms. Some neurologic impairments are hidden disabilities that result in the need for some specialized assistance. Some neurological impairments have a genetic component, while others do not. Neurological impairments include narcolepsy, neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis, spina bifida, Prader-Willi syndrome, and Tourette Syndrome.

Legal Issues, Legal Rights, and Disability

Citizens of the United States obtain rights in three different ways: they are enumerated in our Constitution and Bill of Rights; they are enacted through legislation (local, state or federal) and codified in regulations that further explain or interpret the legislation; or they are the result of court decisions that further define our rights, how they should be interpreted and commonly understood.

Citizens with disabilities have the same rights as citizens who do not have disabilities, among them the right to vote, to own property and dispose of it as they wish, the right to marry, the right to privacy, the right to worship, and freedom of speech, and the right to due process.

After World War II and the Nuremberg Trials, an important concept of informed consent became the standard when medical or other interventions are recommended. This means that a person needs to consent to treatment and needs to understand both the benefits of the treatment and any risks that might derive from the treatment. If we go in for surgery, we are asked to sign a consent form that details what could happen to us as a result of the surgery or of medications that are prescribed. Informed consent also applies to issues like behavior management interventions.

One issue that has involved informed consent and is the source of some tension at the moment is the issue of guardianship. In New York State, the law presumes that anyone who is over 18 can make his or her own decisions. Some individuals with intellectual disabilities may need support in order to make decisions about health care, whether or not to have children, or other life choices. Parents can retain the power to make these decisions for their adult children with intellectual or developmental disabilities if they go to court and petition to remain their adult child’s guardian. Sometimes parents are awarded limited guardianship – they can make some decisions for their adult child with a disability, but not all decisions. Recently a new idea – supported decision-making – is gaining ground. The idea is that the person appoints someone he or she trusts to assist in making important decisions without giving up her or his rights.

When a person with a disability enters public care (or private care) they often give up some rights or parts of rights in order to be eligible for the care they receive. For example, if a person is moving into a group home or apartment program that is run by a service agency, s/he might be giving up some rights to privacy or self-determination in order for the service agency to provide what’s needed. For example, if the person is living with six people and there are two staff members, and five of the residents want to go swimming on Tuesdays, the person who would prefer to stay home may end up going swimming because there is no one to stay home with him or her. Or if the person is used to having a private room s/he may be living with a roommate, at least for a period of time. These issues are typically spelled out so that they are clear before the person moves from one setting to another. While the goal of these organizations should be to provide as much choice as possible – to provide services in the ‘least restrictive environment’ possible, practical issues sometimes mean choices may be limited.

There are five basic laws and regulations that affect disabled children and adults. These are explained below:

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973: Sections 504 and 508 (1973)

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 is very important because its Section 504 mandated that any public entity receiving federal funds needed to be accessible to individuals with disabilities. Since hospitals, federal courts, transportation systems and educational institutions received federal funds, what this meant was that for the first time people who had mobility or sensory issues could take advantage of higher education or the court system, or have access to public transportation. Section 508 mandated that internal federal systems – for example, the telecommunications systems- had to be accessible. This opened the door for people with disabilities to be employed by the federal government. One of the important principles included in the Rehab Act of 1973 was the idea of ‘least restrictive alternative’ or ‘least restrictive environment.’ What this means is that when services are needed – whether they are rehabilitative or educational – they should be provided in the least possible segregated setting, and that people with disabilities should only receive segregated services when absolutely necessary. So, rehabilitation services should be provide in the community, not in segregated settings like hospitals or institutions.

PL 94-142 (1975), renamed IDEA (2004), and Every Student Succeeds Act (2015)

Public Law 94-142, the Education of All Handicapped Children Act – further modified in and renamed Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) mandated a free and appropriate education to all children, whether or not they had a disability. IDEA expanded on this idea, and recent reauthorizations have made some improvements. Important to the original and subsequent modifications is the idea which was embedded in the Rehab Act of 1973 – the idea of ‘least restrictive setting.’ Extending this idea is the concept that the default educational setting should be one where the child with a disability is included or integrated, and only removed from an inclusive classroom for a specific, documented reason (therapy or another documented reason). Also included is the mandate for a written individualized education plan (IEP) that describes the student’s needs and the services to be provided to assist in that child’s education, due process and appeals, formalized input from parents and the student, and periodic review. Additional supports needed by the student are detailed in each student’s IEP.

The Developmental Disabilities Act (1963)

The Developmental Disabilities Act was initially authorized in 1963 by President Kennedy. It is administered under the federal Administration for Community Living (ACL). It is reauthorized periodically and changes are made depending on current needs. For example, in 1975, the State Protection and Advocacy systems were created to address civil rights violations. The Act of 1978 provided for the creation of Developmental Disabilities Planning Councils in each state. These Councils are awarded federal funds and are charged with funding pilot projects that can be widely adopted if they prove to be viable and useful. The DD Act also provided for the creation of University Centers of Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCEDs) which are charged with training clinicians and other staff to work in the community with individuals with developmental disabilities. Protection and Advocacy programs in each state can help with bringing legal actions in cases of violations of individual rights, but they frequently bring actions against more systemic violations of rights. Protection and Advocacy Programs address legal rights of individuals with developmental disabilities, assistive technology, voting accessibility and traumatic brain injury.

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 is the most sweeping legislation for persons with disabilities in the United States. The ADA was signed by President George H. W. Bush in July of 1990, and took effect two years later. The ADA and its amendments of 2008 provide for reasonable accommodation in employment, communication, transportation, and in the use of community resources, like local businesses. While the ADA lays the groundwork for forcing accessibility, it also puts the burden of complaint upon disabled citizens. While the Office of Civil Rights will investigate and prosecute violations of the ADA, reliance for identifying instances of violation rests with individuals with disabilities.

The Olmstead v L.C. Decision of 1999

The Olmstead v L.C. Decision of 1999 was a lawsuit filed by two women living in the Georgia Regional Hospital. Each of the women wanted to live in the community and in each case the professionals treating the women agreed that they would be able to do that. The State of Georgia had not placed the women arguing that their budget was inadequate to support them in the community. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which found that “under Title II of the ADA states are required to place persons with mental disabilities in community settings rather than in institutions when the State’s treatment professionals have determined that community placement is appropriate” and when other conditions have been met. The decision also reaffirmed that individuals with disabilities should not be excluded from life in the community but instead should be included in society.