8.1: Stereotypes, Prejudice, Discrimination and Bias

- Page ID

- 129801

Stereotypes

As children grow, they learn how to behave from those around them. In this socialization process, children are introduced to certain attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs and develop cognitive schemas. Stereotypes are cognitive schemas that incorporate culturally shared representations of social groups and influence information processing related to social categorization (Dovidio et al., 2010; Yzerbyt, 2016). When we encounter someone for the first time, we may not be aware of their cultural or social identities. If we do not have any prior knowledge, we tend to assign individuals to categories based on appearance, age, and the context in which the encounter takes place. This is normal human behavior, as we make sense of the world by putting objects and people into categories. We tend to categorize based on perceived similarities and differences. Obviously, our ability to make viable choices depends on our own degree of experience and knowledge. The less knowledge we have, the more likely we are to fall back on general information we may have acquired informally from friends, family, or media reports. Our mind tries to connect the dots in order to create a complete picture based on the information it already has, which may be scant or faulty. This can provide a very limited, narrowly focused, and potentially distorted impression of the other.

Explaining Prejudice

Prejudice refers to the beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes someone holds about a group. A prejudice is not based on experience; instead, it is a prejudgment, originating outside actual experience. Prejudice may be based on a person's political affiliation, sex, gender, social class, age, disability, religion, sexuality, language, nationality, criminal background, wealth, race, ethnicity, or other personal characteristic. The discussion in this section will largely focus on racial prejudice.

The Blue Eye Experiment highlights how quickly prejudice can be adopted and embedded within a classroom or peers groups without basis. Think about which ways Jane's statements about the children shaped behaviors, values, and beliefs about others and the children's own abilities.

Sociological Explanations of Prejudice

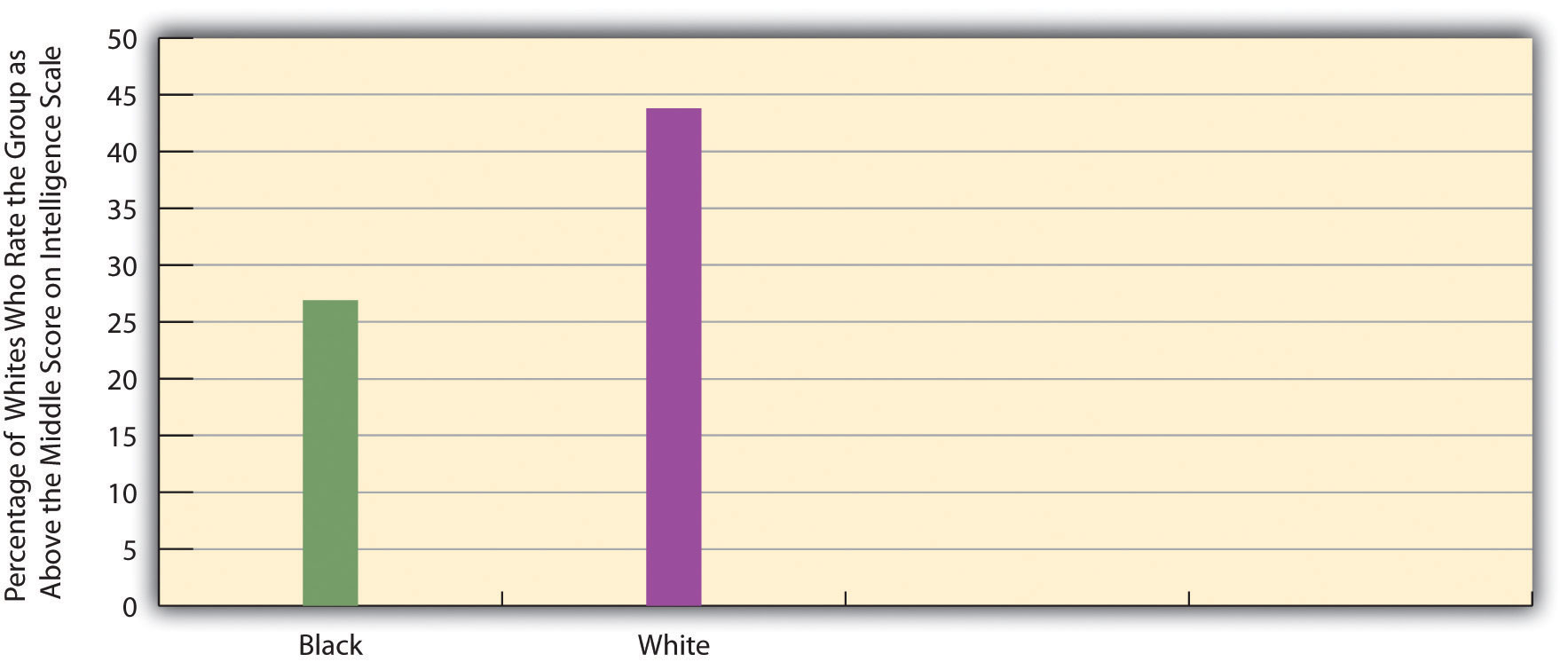

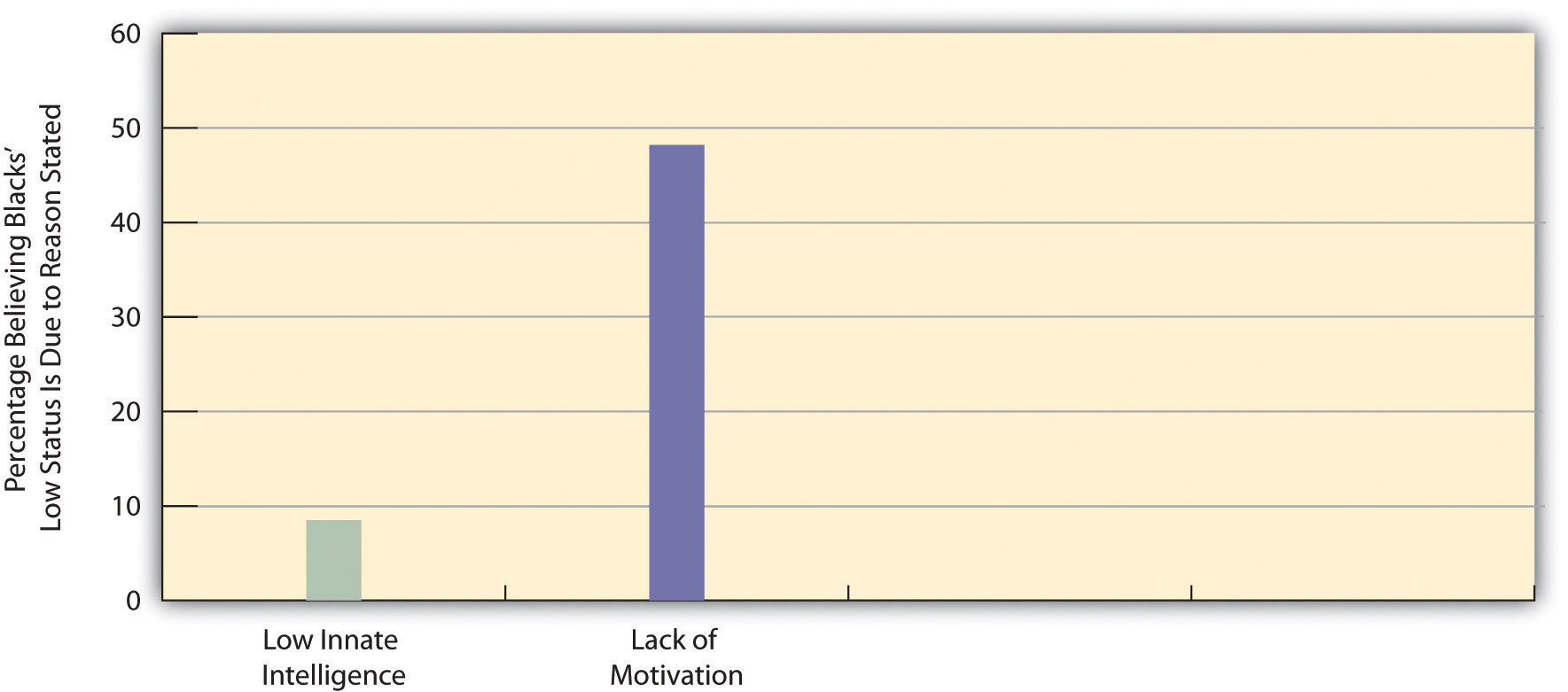

Another explanation of stereotypes and prejudice focuses on supposed cultural deficiencies of people of color (Murray, 1984). These deficiencies include a failure to value hard work and, for African Americans, a lack of strong family ties, and are said to account for the poverty and other problems facing these minorities. As we saw earlier, more than half of non-Latino whites think that Blacks’ poverty is due to their lack of motivation and willpower. Ironically some scholars find support for this cultural deficiency view in the experience of many Asian Americans, whose success is often attributed to their culture’s emphasis on hard work, educational attainment, and strong family ties (Min, 2005). If that is true, these scholars say, then the lack of success of other people of color stems from the failure of their own cultures to value these attributes.

How accurate is the cultural deficiency argument? Whether people of color have “deficient” cultures remains hotly debated (Bonilla-Silva, 2009). Many social scientists find little or no evidence of cultural problems in minority communities and say the belief in cultural deficiencies is an example of symbolic racism that blames the victim. Citing survey evidence, they say that poor people of color value work and education for themselves and their children at least as much as wealthier white people do (Holland, 2011; Muhammad, 2007). Yet other social scientists, including those sympathetic to the structural problems facing people of color, believe that certain cultural problems do exist, but they are careful to say that these cultural problems arise out of the structural problems.

In these two studies, we can see how the deficit theory can impact children even at the earliest ages. In the landmark Yale study by Gilliam (2016) the findings reveal that when expecting challenging behaviors, teachers gazed longer at Black children, especially Black boys. The teachers indicated that they looked for and expected problematic behavior from Black boys. Moreover, Gregory and Robert (2017) found that teacher's suspend Black children three times more than White children for similar situations. This suggests that Black students are being treated differently based on race. The researcher concluded that teachers that come with deficit thinking, believing that Black boys have a tendency toward disruption or violence and who are known to be lenient in disciplining White children compounds the issue that Black children are being "pushed" out of the education system at a young age.

The Changing Nature of Prejudice

Types of Active Prejudice

Discrimination

Discrimination in this context refers to the arbitrary denial of rights, privileges, and opportunities to members of these groups. The use of the word arbitrary emphasizes that these groups are being treated unequally not because of their lack of merit but because of their race and ethnicity. Usually prejudice and discrimination go hand-in-hand, but Robert Merton (1949) stressed this is not always so. Sometimes we can be prejudiced and not discriminate, and sometimes we might not be prejudiced and still discriminate.

Institutional Discrimination

Individual discrimination is important to address, but at least as consequential in today’s world is institutional discrimination, or discrimination that pervades the practices of whole institutions, such as housing, medical care, law enforcement, employment, and education. This type of discrimination does not just affect a few isolated people of color. Instead, it affects large numbers of individuals simply because of their race or ethnicity. Sometimes institutional discrimination is also based on gender, disability, and other characteristics.

The bottom line is this: Institutions can discriminate even if they do not intend to do so. Consider height requirements for police. Before the 1970s, police forces around the United States commonly had height requirements, say five feet ten inches. As women began to want to join police forces in the 1970s, many found they were too short. The same was true for people from some racial/ethnic backgrounds, such as Latinos, whose stature is smaller on the average than that of non-Latino whites. Of course, even many white males were too short to become police officers, but the point is that even more women, and even more men of certain ethnicities, were too short.

This gender and ethnic difference is not, in and of itself, discriminatory as the law defines the term. The law allows for bona fide (good faith) physical qualifications for a job. As an example, we would all agree that someone has to be able to see to be a school bus driver; sight therefore is a bona fide requirement for this line of work. Thus even though people who are blind cannot become school bus drivers, the law does not consider such a physical requirement to be discriminatory.

But were the height restrictions for police work in the early 1970s bona fide requirements? Women and members of certain ethnic groups challenged these restrictions in court and won their cases, as it was decided that there was no logical basis for the height restrictions then in effect. The courts concluded that a person did not have to be five feet ten inches to be an effective police officer. In response to these court challenges, police forces lowered their height requirements, opening the door for many more women, Latino men, and some other men to join police forces (Appier, 1998). Whether police forces back then intended their height requirements to discriminate, or whether they honestly thought their height requirements made sense, remains in dispute. Regardless of the reason, their requirements did discriminate.

Institutional discrimination affects the life chances of children and families of color in many aspects of life today. To illustrate this, we turn briefly to some examples of institutional discrimination that have been the subject of government investigation and scholarly research. A 2012 report from the American Psychological Association’s Task Force on Preventing Discrimination and Promoting Diversity found that biases – including implicit biases – are pervasive across people and institutions. In the educational setting, children from minoritized communities have less access to experienced teachers, advanced coursework, and resources and are also more harshly punished for minor behavioral infractions occurring in the school setting. They are less likely to be identified for and receive special education services, and in some states, school districts with more nonwhite children receive lower funding at any given poverty level than districts with more white children (U.S Department of education, 2017).

Implicit Bias

Sometimes biases exist in people; they’re just more subtle. These are unexamined and sometimes unconscious but real in their consequences. They are automatic, ambiguous, and ambivalent, and nonetheless are biased, unfair, and disrespectful to the belief in equality.

Social psychologists have developed several ways to measure this relatively automatic own-group preference, the most famous being the implicit bias test. Take the implicit bias test to explore your own possible biases. Then watch the Kirwan Institute video examine ways teachers bias can create negative impacts for people of color.

Microaggressions

Microaggressions have been described by many as "small paper cuts" that represent all the times that someone says or does something that marginalizes you because of your cultural frame of reference. Which of these statements is a Microaggression?

If it comes to attention that a Microaggression occurred, from a reflective disposition all involved should consider:

- Why is the statement problematic- who might be affected by the statement?

- How might the statement be intended as a compliment?

- What are ways to be upstanders- someone who recognizes when something is wrong and speaks up to make it right?

Impact of Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Bias

Addressing Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Bias

Institutional

To begin to dismantle structural discrimination the Academy of Pediatrics (2019) suggest the following:

- Acknowledge that educational and health equity is unachievable unless racism is addressed through interdisciplinary partnerships with other organizations that have developed campaigns against racism.

- Advocate for improvements in the quality of education in segregated urban, suburban, and rural communities designed to better optimize vocational attainment and educational milestones for all students.

- Advocate for federal and local policies that support implicit-bias training in schools and robust training of educators in culturally competent classroom management to improve disparities in academic outcomes and disproportionate rates of suspension and expulsion among students of color, reflecting a systemic bias in the educational system.

- Encourage community-level advocacy with members of those communities disproportionately affected by racism to develop policies that advance social justice.

- Advocate for fair housing practices, including access to housing loans and rentals that prohibit the persistence of historic “redlining.”

- Advocate for funding and dissemination of rigorous research that examine the impact of policy changes and community-level interventions on reducing the health effects of racism and other forms of discrimination on youth development.

Individual

Many of the efforts used to address prejudice and intolerance on the individual level involve education, that is, increasing intercultural awareness or sensitizing individuals to difference. However, intolerance is complex, involving not only a cognitive side, but also affective (emotional), behavioral, and structural/political components. One approach for addressing intolerance is contact theory, originally the "contact hypothesis," as developed by US psychologist Gordon Allport (1979). Allport suggested that direct contact between members of different groups – under certain conditions – could lead to reducing prejudice and conflict. The conditions for success he laid out, are that 1) there be equal status between the groups, 2) both groups have common goals for the encounter, 3) both groups focus on cooperation rather than competition, and finally 4) the process be supported by an authority of some kind, such as a government agency. This approach has been used effectively in such conflicts as the relationship between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland and in the reconciliation talks between whites and blacks in post-apartheid South Africa. It is the underlying assumption for the benefits derived from school exchanges.

Relying on faulty information leads us to make generalizations that may be far removed from reality. We can overcome the distortion of the "single story", as Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Adichie puts it, in a number of ways (Adichie, 2009). The most effective antidote is to gain greater real knowledge of other cultures through direct contact. That can come from travel, study abroad, service learning, online exchanges, or informal means of making contact. Following news reports on what's happening outside our immediate area can also be valuable, particularly if we seek out reliable, objective reporting. What can be helpful in that regard is to try to find multiple sources of information. Another way to gain insight into other cultures is through stories, told in novels, autobiographies, or movies. The more perspectives we have on a given culture, the less likely it is that we will extrapolate from a single experience to make generalizations about an entire group.

Research by Allport and others has shown that bringing groups together into contact with one another does not in itself provide a guarantee of improved attitudes or enlightened views vis-à-vis the other group. Allport’s contact theory shows that the context and conditions of the encounter will shape success or failure. Even encounters when conducted under ideal and carefully supervised conditions may still have mixed results. That might include benefits for some students and adverse reactions from others, including reactions bordering on culture shock.

References

Gilliam, W.S., Ph., D., Maupin, A.N., Reyes, C.R., Accavitti, M.R., B., S., & Shic, F. (2016). Do Early Educators’ Implicit Biases Regarding Sex and Race Relate to Behavior Expectations and Recommendations of Preschool Expulsions and Suspensions? Semanticscholar.

Merton, R. K. (1949). Social Theory and Social Structure. Free Press.

Min 2005 Min, P. G. (Ed.). (2005). Asian Americans: Contemporary trends and issues (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Murray, C. (1984). Losing ground: American social policy, 1950–1980. New York, NY: Basic Books.