8.5: Gender Socialization

- Page ID

- 116257

Sex and Gender

Although the terms "sex" and "gender" are sometimes used interchangeably and do in fact complement each other, they nonetheless refer to different aspects of what it means to be a woman or man in any society.

Sex refers to biological, physical and physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics such as height and muscularity, as well as genetic differences (e.g., chromosomes). Male sexual and reproductive organs include the penis and testes. Female sexual and reproductive organs include clitoris, vagina and ovaries. Biological males have XY chromosome and biological females have XX chromosome but biological sex is not as easily defined or determined as you might expect. For example, does the presence of more than one X mean that the XXY person is female or does the presence of a Y mean that the XXY person is male? The existence of sex variations fundamentally challenges the notion of a binary biological sex.

Gender is a term that refers to social or cultural distinctions and roles associated with being male or female. Gender is not determined by biology in any simple way. At an early age, we begin learning cultural norms for what is considered masculine (trait of a male) and feminine (trait of a female). Gender is conveyed and signaled to others through clothing and hairstyle, or mannerisms like tone of voice, physical bearing, and facial expression. For example, children in the United States may associate long hair, fingernail polish or dresses with femininity. Later in life, as adults, we often conform to these norms by behaving in gender specific ways: men build houses and women bake cookies (Marshall, 1989; Money et al., 1955; Weinraub et al., 1984). It is important to remember that behaviors and traits associated with masculinity and femininity are culturally defined. For example, in American culture, it is considered feminine to wear a dress or skirt; however, in many Middle Eastern, Asian, and African cultures, dresses or skirts (often referred to as sarongs, robes, or gowns) are worn by males and are considered masculine. The kilt worn by a Scottish male does not make him appear feminine in his culture.

Our understanding of gender begins very early in life – often before we are born. Western cultures, expecting parents are asked whether they are having a girl or a boy and immediately judgments are made about the child. Boys will be active and presents will be blue while girls will be delicate and presents will be pink. In some Asian and Muslim cultures a male child is valued more favorably than a female child (Matsumoto & Juang, 2013) and female fetuses may be aborted or female infants abandoned.

Gender Socialization

As you watch the overview of gender theories, reflect on your earliest memories related to gender:

- When was the first time you understood how your gender would affect your life?

- How did your understanding of gender develop as you grew older, and as the world changed around you?

- Were your own experiences related to gender positive or negative?

Agents of Socialization related to Gender

The Family

Peers

Schools

In the past, many schools were organized and structured along gender lines which socialized males and females differently. Even though most schools are the integrated traditional disproportionate outcomes are still prevalent such where females focus on social science fields for employment and males are more inclined to to focus on STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) subjects. These patterns can be observed with career and study choices already prior to entering the work force (UNESCO, 2017).

This may be a product of societal influence, where children see behavioral cues from their teachers and caregivers signaling differences in competencies for girls and boys in school years. This hidden curriculum is determinantal to girls and privileges boys in classrooms. Research from suggests a teacher's own underlying beliefs about gendered behavior may cause them to act in favor of the boys such as calling on them more in class or asking boys cognitively more complex questions. This ultimately leads to the unfolding of a self-fulfilling prophecy in the academic and behavioral performances of the students (Hedges & Nowell, 1995).

Mass Media

Gender socialization also occurs through the mass media (Dow & Wood, 2006). On children’s television shows, the major characters are male. On Nickelodeon, for example, the very popular SpongeBob SquarePants is a male, as are his pet snail, Gary; his best friend, Patrick Star; their neighbor, Squidward Tentacles; and SpongeBob’s employer, Eugene Crabs. Of the major characters in Bikini Bottom, only Sandy Cheeks is a female.

Gender Roles

As mentioned earlier, gender roles are well-established social constructions that may change from culture to culture and over time. In American culture, we commonly think of gender roles in terms of gender stereotypes, or the beliefs and expectations people hold about the typical characteristics, preferences, and behaviors of men and women.

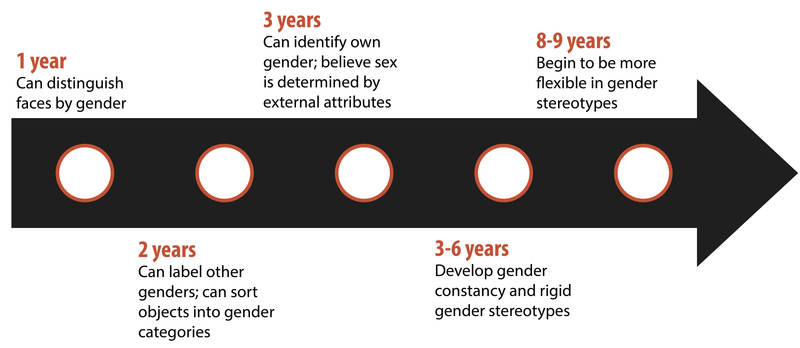

By the time we are adults, our gender roles are a stable part of our personalities, and we usually hold many gender stereotypes. When do children start to learn about gender? Very early. By their first birthday, children can distinguish faces by gender. By their second birthday, they can label others’ gender and even sort objects into gender-typed categories. By the third birthday, children can consistently identify their own gender (see Martin, Ruble, & Szkrybalo, 2002, for a review). At this age, children believe sex is determined by external attributes, not biological attributes. Between 3 and 6 years of age, children learn that gender is constant and can’t change simply by changing external attributes, having developed gender constancy. During this period, children also develop strong and rigid gender stereotypes. Stereotypes can refer to play (e.g., boys play with trucks, and girls play with dolls), traits (e.g., boys are strong, and girls like to cry), and occupations (e.g., men are doctors and women are nurses). These stereotypes stay rigid until children reach about age 8 or 9. Then they develop cognitive abilities that allow them to be more flexible in their thinking about others.

There are also psychological theories that partially explain how children form their own gender roles after they learn to differentiate based on gender. The first of these theories is gender schema theory. Gender schema theory argues that children are active learners who essentially socialize themselves. In this case, children actively organize others’ behavior, activities, and attributes into gender categories, which are known as schemas. These schemas then affect what children notice and remember later. People of all ages are more likely to remember schema-consistent behaviors and attributes than schema-inconsistent behaviors and attributes. So, people are more likely to remember men, and forget women, who are firefighters. They also misremember schema-inconsistent information. If research participants are shown pictures of someone standing at the stove, they are more likely to remember the person to be cooking if depicted as a woman, and the person to be repairing the stove if depicted as a man. By only remembering schema-consistent information, gender schemas strengthen more and more over time.

Gender stigma awareness is the extent to which children, particularly adolescents, are cognizant of being judged by their gender (e.g., boys are more delinquent than girls, boys are better at math; girls are more hardworking that boys, girls are not good at math) affect how people perceive and interact with them. This this fear of gender stigma leads many boys to engage in risk taking behaviors such fighting, delinquent behaviors, and substance abuse to prove their masculinity (Kwaning et al., 2021).

A second theory that attempts to explain the formation of gender roles in children is social learning theory. Social learning theory argues that gender roles are learned through reinforcement, punishment, and modeling. Children are rewarded and reinforced for behaving in concordance with gender roles and punished for breaking gender roles. In addition, social learning theory argues that children learn many of their gender roles by modeling the behavior of adults and older children and, in doing so, develop ideas about what behaviors are appropriate for each gender. Social learning theory has less support than gender schema theory—research shows that parents do reinforce gender-appropriate play, but for the most part treat their male and female children similarly (Lytton & Romney, 1991).

- What did they decide to do?

- What problems did it create?

- Why did one doctor voice his concern?

- What is your opinion of this?

Gender Differences

Differences between males and females can be based on (a) actual gender differences (i.e., men and women are actually different in some abilities), (b) gender roles (i.e., differences in how men and women are supposed to act), or (c) gender stereotypes (i.e., differences in how we think men and women are). Sometimes gender stereotypes and gender roles reflect actual gender differences, but sometimes they do not.

What are actual gender differences? In terms of language and language skills, girls develop language skills earlier and know more words than boys; this does not, however, translate into long-term differences. Girls are also more likely than boys to offer praise, to agree with the person they’re talking to, and to elaborate on the other person’s comments; boys, in contrast, are more likely than girls to assert their opinion and offer criticisms (Leaper & Smith, 2004). In terms of temperament, boys are slightly less able to suppress inappropriate responses and slightly more likely to blurt things out than girls (Else-Quest et al., 2006).

With respect to aggression, boys exhibit higher rates of unprovoked physical aggression than girls, but no difference in provoked aggression (Hyde, 2005). Some of the biggest differences involve the play styles of children. Boys frequently play organized rough-and-tumble games in large groups, while girls often play less physical activities in much smaller groups (Maccoby, 1998). There are also differences in the rates of depression, with girls much more likely than boys to be depressed after puberty. After puberty, girls are also more likely to be unhappy with their bodies than boys.

However, there is considerable variability between individual males and individual females. Also, even when there are mean level differences, the actual size of most of these differences is quite small. This means, knowing someone’s gender does not help much in predicting his or her actual traits. For example, in terms of activity level, boys are considered more active than girls. However, 42% of girls are more active than the average boy. Furthermore, many gender differences do not reflect innate differences, but instead reflect differences in specific experiences and socialization. For example, one presumed gender difference is that boys show better spatial abilities than girls. However, Tzuriel and Egozi (2010) gave girls the chance to practice their spatial skills (by imagining a line drawing was different shapes) and discovered that, with practice, this gender difference completely disappeared.

Many domains we assume differ across genders are really based on gender stereotypes and not actual differences. Based on large meta-analyses, the analyses of thousands of studies across more than one million people, research has shown: Girls are not more fearful, shy, or scared of new things than boys; boys are not more angry than girls and girls are not more emotional than boys; boys do not perform better at math than girls; and girls are not more talkative than boys (Hyde, 2005).

References

Dow, B. J., & Wood, J. T. (2006). The SAGE handbook of gender and communication. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Else-Quest, N. M., Hyde, J. S., Goldsmith, H. H., & Van Hulle, C. A. (2006). Gender differences in temperament: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 33–72. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.33

Hedges, L. V., & Nowell, A. (1995). Sex differences in mental scores, variability, and numbers of high-scoring individuals. Science, 269, 41–45.

Hyde, J. S. (2005). The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60(6), 581–592.

King, W. C., Miles, E. W., & Kniska, J. (1991). Boys will be boys (and girls will be girls): The attribution of gender role stereotypes in a gaming situation. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 25(11-12), 607–623.

Klein, N. (2007). The Shock Doctrine: The rise of disaster capitalism. Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt and Company.

Kwaning K, Wong M, Dosanjh K, Biely C, Dudovitz R. (2021). Gender stigma awareness is associated with adolescent risky health behaviors. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5):1-12.

Leaper, C., & Smith, T. E. (2004). A meta-analytic review of gender variations in children’s language use: Talkativeness, affiliative speech, and assertive speech. Developmental Psychology, 40(6), 993–1027.

Lever, J. (1978). Sex differences in the complexity of children's play and games. American Sociological Review, 43(4), 471–483.

Lindsey, L. L. (2011). Gender roles: A sociological perspective. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Lytton, H., & Romney, D. M. (1991). Parents’ differential socialization of boys and girls: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 109(2), 267–296.

Maccoby, E. E. (1998). The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard University Press.

Marshall, H. H. (1989). The development of self-concept. Young Children, 44, 44-51.

Martin, C. L., Ruble, D. N., & Szkrybalo, J. (2002). Cognitive theories of early gender development. Psychological Bulletin, 128(6), 903–933.

Matsumoto, D. & Juang, L. (2013). Culture & Psychology (5th ed.). Cengage.

Milillo, D. (2008). Sexuality sells: A content analysis of lesbian and heterosexual women’s bodies in magazine advertisements. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 12(4), 381-392.

Money, J., Hampson, J. G., & Hampson, J. (1955). An examination of some basic sexual concepts: The evidence of human hermaphroditism. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, 97, 301–319.

Sadker, M. P., & Sadker, D. M. (1994). Failing at fairness: How America's schools cheat girls. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

Tenenbaum, H. R. (2009). 'You'd be good at that’: Gender patterns in parent-child talk about courses. Social Development, 18(2), 447–463.

Thorne, B. (1993). Gender play: Girls and boys in school. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press.

Tzuriel, D., & Egozi, G. (2010). Gender differences in spatial ability of young children: The effects of training and processing strategies. Child Development, 81(5), 1417–1430.

UNESCO (2017). Cracking the code: Girls’ and Women’s Education in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM).

Weinraub, M., Clemens, L., Sockloff, A., Ethridge, T., Gracely, E., & Myers, B. (1984). The development of sex role stereotypes in the third year: Relationships to gender labeling, gender identity, sex-types toy preference, and family characteristics. Child Development, 55, 1493-1503.

Yoder, J. D., Christopher, J., & Holmes, J. D. (2008). Are television commercials still achievement scripts for women? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(3), 303-11