3.2: Breast Milk- Composition, Benefits and Rates

- Page ID

- 139635

Overview of Breast Milk and Breastfeeding

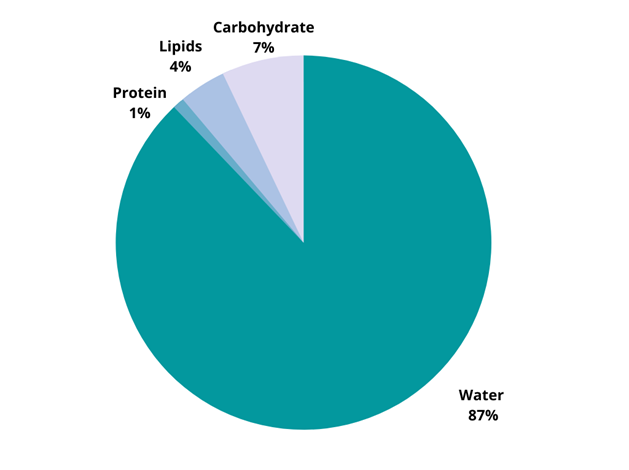

Feeding an infant breast milk is one of the best ways to start them off on the path of lifelong health. Breast milk consists of 87% water, 1% protein, 4% lipids, and 7% carbohydrate, displayed in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) (Boquien, 2018; Martin, Ling & Blackburn, 2016). It also contains many vitamins and minerals. Another unique aspect of human milk is the high proportion of fatty acids, including the two essential fatty acids linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid. These fatty acids are important for infant brain development. In addition to nutrients, human milk includes bioactive substances and immunologic properties that support infant health and development (Le Doare, Holder, Bassett & Pannaraj, 2018). [1] [2]

In the initial week after pregnancy, the mother secretes colostrum, a thick yellow liquid. From days 7 to 14, the mother secretes transitional milk, a combination of colostrum and mature milk. After two weeks, the mature milk is formed and produced (Ballard & Morrow, 2013). The breast milk can be divided into the bluish-gray foremilk, present at the beginning of a feed which contains less fat, and the creamy white hindmilk secreted towards the end of a feed that is rich in fat. The composition of breast milk can differ depending on maternal health and diet, environmental exposure, and gestational age, amongst other factors (Martin, Ling & Blackburn, 2016). [4]

Breast milk can support an infant’s nutrient needs for about the first 6 months of life, with the exception of vitamin D and potentially iron. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends infants be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life and encourages the continuation of breast milk in combination with complementary feeding of solid foods for 2 years and beyond (World Health Organization, 2003). Exclusive breast milk feeding refers to an infant consuming only human milk, and not in combination with infant formula and/or complementary foods or beverages (including water), except for medications or vitamin and mineral supplementation. [5] [6]

A newborn may require breastfeeding every 1 to 3 hours for 10 to 20 minutes on average; however, the frequency and duration of breastfeeding sessions decrease as the child gets older and they can receive more milk in less time. On the third day after birth, the amount of breastmilk taken by the infant is about 300 to 400 milliliters each 24 hours, and on the fifth day 500 to 800 milliliters. Infant milk consumption averages about 800 milliliters each day during the first 6 months. [8]

While breast milk is encouraged, not all families are able to provide it for their infants for various reasons. For example, a family may choose not to breastfeed, a child may be adopted, or the mother may be unable to produce a full milk supply or may be unable to pump and store milk safely due to family or workplace conditions. If human milk is unavailable, infants should be fed an iron-fortified commercial infant formula (i.e., labeled “with iron”) regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which is based on standards that ensure nutrient content and safety. Infant formulas are designed to meet the nutritional needs of infants and are not needed beyond 12 months. It is important to take precautions to ensure that expressed human milk and prepared infant formula are handled and stored safely. [9]

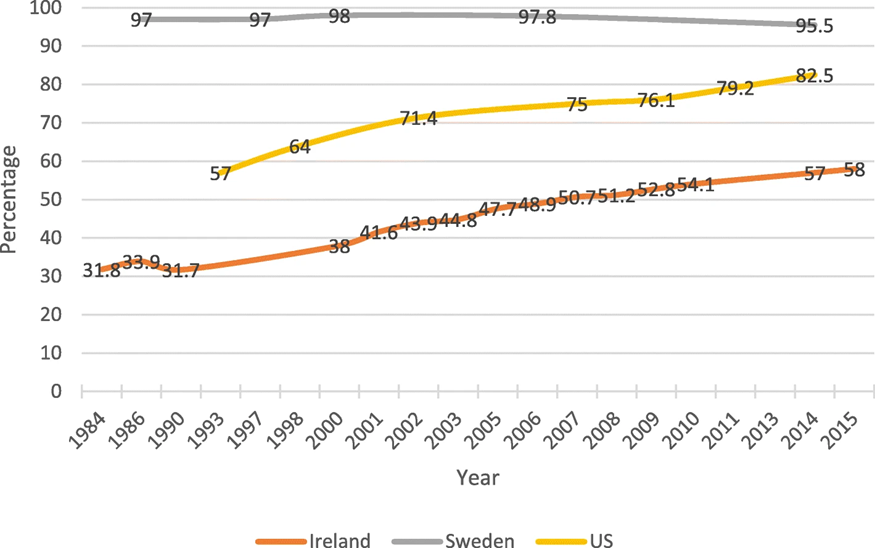

Despite the benefits of breast milk, breastfeeding rates remain low in many countries. Globally, only 37% of infants between 0 to 6 months of age are exclusively breastfed, with the highest percentage (47%) among infants in South-East Asia (World Health Organization, 2014). In Malaysia, while 94.7% of infants were breastfed at least once, only 14.5% practiced exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months (Fatimah et al., 2010). In Lebanon only 38% of infants are exclusively breastfed during the first month of life and around 2% are breastfeeding at 6 months of age (Hamade et al., 2013). Breastfeeding, both initiation and duration, has been increasing steadily among high-income countries since the late 1970’s (Lubold, 2019; Wolf, 2003); however, in some countries, breastfeeding rates have increased at a much faster rate than in others. For example, Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows the proportion of women who initiated breastfeeding in Ireland, Sweden, and the US from 1984 to 2015. While Sweden has consistently had higher rates, both Ireland and the U.S. have seen a positive increase in breastfeeding initiation rates over time. [10] [11] [12]

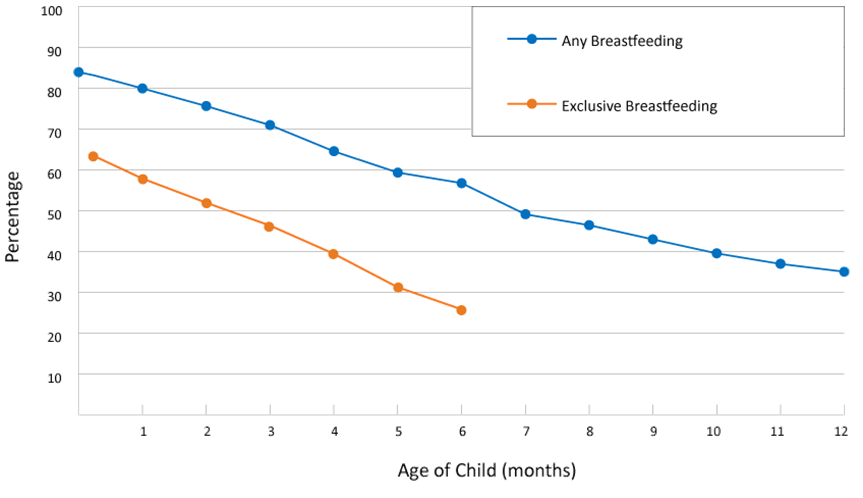

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows the rate of any amount of breastfeeding during the first twelve months for children born in 2018 in the U.S. Younger infants are more likely to be breastfed as approximately 80% of one month old infants receive some amount of breastfeeding compared to under 60% at six months and under 40% at twelve months. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) also shows the rate of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months in 2018. While nearly 60% of infants are exclusively breastfed at one month of age, less than 30% are at six months of age. Rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration differ by state. In California in 2017, 90.3% of newborns were breastfed at least once, 67.1% were still breastfeeding at six months and 43.3% were still breastfeeding at twelve months; however, only 50.1% were exclusively breastfed for the first three months and only 28.2% were exclusively breastfed for the first six months. Louisiana had the lowest percentage of infants who ever breastfed (66.2%) while Minnesota had the highest at 95.3%. At six months, the national average for infants still breastfeeding was 58.3%, which dropped to 35.3% at twelve months. Furthermore, there is a racial disparity in both the initiation and duration of breastfeeding in the U.S. (Beauregard et al., 2019). Black infants had a significantly lower rate of having ever been breastfed at 3 months (58.0%) than did white infants (72.7%); at 6 months, the rates were 44.7% among Black infants and 62.0% among white infants. [14] [15] [16] [17]

The rate of exclusive breastfeeding is lower among working mothers (Chen, Wu & Chie, 2006; Kimbro, 2006; Tan, 2011). In a survey comprising 228,000 new mothers of varying employment status in the United States, the breastfeeding rate at six months was statistically lower among mothers employed full time (26.1%), as compared with part-time (36.6%) and non-working mothers (35.0%) (Ryan, Zhou & Arensberg, 2006). Returning to work, time costs, and unconducive workplaces are common reasons for early breastfeeding cessation among working mothers (Brown et al., 2014; Ong, Yap, Li & Choo, 2005; Smith & Forrester, 2013). [19]

Child care centers can play a crucial role in supporting breastfeeding mothers (Lundquist, McBride, Donovan & Kieffer, 2019; Marhefka et al., 2019). Lundquist et al. (2019) highlighted the importance of educating child care center staff about breastfeeding as well as creating supportive policies and practices in childcare centers. Furthermore, Marhefka et al. (2019) concluded that breastfeeding-friendly child care centers could contribute to creating a cultural shift towards breastfeeding continuation. [20]

While child care centers can play an important role, they still have much progress to make in supporting breastfeeding mothers and their children. For example, Mattar et al. (2019) showed very low rates of breastfeeding among children in Lebanese daycare centers. Studies from the U.S. have found lower rates of breastfeeding in center-based programs, compared to home-based programs and an overall lack of supportive policies and practices in center-based care programs (Dieterich, Caplan, Yang & Demirci, 2020; Machado, 2015). [21]

Studies on breastfeeding worldwide indicate the importance of policy recommendations and support at the national and local levels (Gomez-Pomar & Blubaugh, 2018; Horton & Victoria, 2013; World Health Organization, 1998). Research in the United States and Australia showed that encouragement, written policies, resource/materials distribution, and training for breastfeeding were significantly higher in Australia, despite similar rates of availability of facilities such as places to breastfeed and refrigerators for storage in childcare facilities (Cameron et al., 2012). In Japan, there is a lack of understanding of breastfeeding in the workplace and there are perceived challenges such as the burden of breastfeeding management in childcare facilities (Yabe et al., 2021) [23]

To support breastfeeding, child care centers can create spaces where mothers can comfortably breastfeed their children and/or pump breastmilk. Additionally, centers can have a devoted space and organized system for storing pumped breastmilk and a specific space for cleaning the pumping parts. All child care programs can lower a breastfeeding mother’s anxiety by allowing her to feed her infant on-site, having a posted breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated, making sure procedures for storing and handling breast milk and feeding breastfed infants are in place, and making sure staff members are well-trained in these procedures. Data from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II, a longitudinal study that followed mothers from the third trimester until children were age 1 year, found that breastfeeding at 6 months was significantly associated with support from child care providers to feed expressed breast milk to infants and allow mothers to breastfeed on-site before or after work (Fein, Grummer-Strawn & Raju, 2008; Fein, Mandal & Roe, 2008). [24]

Many mothers need to leave their babies at a child care facility to work. The longer the mother is at work, the longer the baby will spend time with the childcare worker. Hence, childcare workers and settings can be primary sources of support for working mothers who want to breastfeed by helping to store, handle and feed the baby with breastmilk while the mother is at work (Cameron et al., 2012). In studies examining child care providers’ support of breastfeeding, Javanparast et al. (2012) and Batan & Scanlon (2013) found that by helping to feed expressed breastmilk and allowing mothers to breastfeed before or after work, childcare providers helped mothers maintain breastfeeding at six months postpartum. Nevertheless, Lucas et al. (2013) found some knowledge deficit among childcare providers in the area of health benefits and proper handling of breastmilk, indicating the need for adequate support and training for them to help working mothers. [25]

Childcare administrators are well aware of the benefits of breastmilk, but express perceived risk with the handling and feeding of breast milk (Schafer et al., 2021). This is reinforced by the fact that previous studies have also reported that the lack of literacy regarding breastfeeding and the perceived risk of handling breast milk among childcare facility administrators were barriers (Lucas et al., 2013; Marhefka et al., 2019; Schafer et al., 2021). [26]

To support the use of breast milk in childcare centers, caregivers and staff must be knowledgeable of proper handling and storage of both breastmilk and infant formula: [28]

- Before handling breast milk wash your hands well with soap and water.

- Refrigerate freshly expressed breast milk within 4 hours for up to 4 days. Previously frozen and thawed breast milk should be used within 24 hours. Thawed breast milk should never be refrozen. Refrigerate prepared infant formula for up to 24 hours.

- If preparing powdered infant formula, use a safe water source and follow instructions on the label.

- Do not store breast milk in the door of the refrigerator or freezer. This will help protect the breast milk from temperature changes from the door opening and closing.

- Do not use a microwave to warm breast milk or infant formula. Microwaving can destroy nutrients in breast milk and create hot spots, which can burn a baby’s mouth. Warm safely by placing the sealed container of breast milk or infant formula in a bowl of warm water or under warm, running tap water.

- Once it has been offered to the infant, use or discard leftovers quickly (within 2 hours for breast milk or 1 hour for infant formula).

- Thoroughly wash all infant feeding items, such as bottles and nipples.

- Consider sanitizing feeding items for infants younger than 3 months of age, infants born prematurely, or infants with a compromised immune system.

- Freshly expressed or pumped milk can be stored:

- At room temperature (77°F or colder) for up to 4 hours.

- In the refrigerator for up to 4 days.

- In the freezer for about 6 months is best; up to 12 months is acceptable. Although freezing keeps food safe almost indefinitely, recommended storage times are important to follow for the best quality.

[1] “Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025” by U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is in the public domain.

[2] Boquien (2018). Human milk: An ideal food for nutrition of preterm newborn. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 6, 295. CC by 4.0

[3] Image by Todd LaMarr is licensed under CC by 4.0

[4] Shah et al., (2019). Physiology, Breast Milk. CC by 4.0

[5] Abou Jaoude et al., (2021). Factors related to breastfeeding support in Lebanese daycare centers: A qualitative study among daycare directors and employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6205.

[6] “Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025” by U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is in the public domain.

[1] Image from Luiza Braun on Unsplash.

[8] Shah et al., (2019). Physiology, Breast Milk. CC by 4.0

[9] “Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025” by U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is in the public domain.

[10] Suan et al., (2016). Childcare workers’ experiences of supporting exclusive breastfeeding in Kuala Muda District, Malaysia: A qualitative study. International Breastfeeding Journal, 12(1), 1-8. CC by 4.0

[11]Abou Jaoude et al., (2021). Factors related to breastfeeding support in Lebanese daycare centers: A qualitative study among daycare directors and employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6205.

[12] Lubold (2019). Historical-qualitative analysis of breastfeeding trends in three OECD countries. International Breastfeeding Journal, 14(1), 1-12. CC by 4.0

[13] Image from Lubold (2019). Historical-qualitative analysis of breastfeeding trends in three OECD countries. International Breastfeeding Journal, 14(1), 1-12. CC by 4.0

[14] Abou Jaoude et al., (2021). Factors related to breastfeeding support in Lebanese daycare centers: A qualitative study among daycare directors and employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6205.

[15] Suan et al., (2016). Childcare workers’ experiences of supporting exclusive breastfeeding in Kuala Muda District, Malaysia: a qualitative study. International Breastfeeding Journal, 12(1), 1-8. CC by 4.0

[16] “Breastfeeding Report Card” from the CDC is in the public domain.

[17] Beauregard et al., (2019). Racial disparities in breastfeeding initiation and duration among US infants born in 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(34), 745. Public domain.

[18] Image from the CDC is in the public domain.

[19] Suan et al., (2016). Childcare workers’ experiences of supporting exclusive breastfeeding in Kuala Muda District, Malaysia: a qualitative study. International Breastfeeding Journal, 12(1), 1-8. CC by 4.0

[20] Abou Jaoude et al., (2021). Factors related to breastfeeding support in Lebanese daycare centers: A qualitative study among daycare directors and employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6205.

[21] Abou Jaoude et al., (2021). Factors related to breastfeeding support in Lebanese daycare centers: A qualitative study among daycare directors and employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6205.

[22] Image from Luiza Braun on Unsplash.

[23] Yabe et al., (2021). Perception and handling of breastmilk by childcare staff: A qualitative study of childcare facilities in Japan. Journal of General and Family Medicine. CC by NC 4.0

[24] “Support for Breastfeeding in Early Care and Education” from the CDC is in the public domain.

[25] Suan et al., (2016). Childcare workers’ experiences of supporting exclusive breastfeeding in Kuala Muda District, Malaysia: a qualitative study. International Breastfeeding Journal, 12(1), 1-8. CC by 4.0

[26] Yabe et al., (2021). Perception and handling of breastmilk by childcare staff: A qualitative study of childcare facilities in Japan. Journal of General and Family Medicine. CC by NC 4.0

[27] Image from Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash.

[28] “Proper Storage and Preparation of Breast Milk” from the CDC is in the public domain.