5.2: Mental Health in Infancy and Toddlerhood

- Page ID

- 139789

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Mental Health

While it is widely accepted that we are in the midst of a mental health crisis for young people, what is often missed is that the precursors of mental health challenges can begin as early as the perinatal period and also in early infancy (Robinson et al., 2008). This makes the infant and early childhood period a crucial window for intervention, with the goal of promoting good mental health for infants and young children (Robinson et al., 2008). [1]

Good mental health in infancy and toddlerhood refers to healthy social and emotional development. It includes a child’s ability to experience, regulate and express emotions, to develop close and secure interpersonal relationships, and to explore the environment and learn (Clinton, Feller & Williams, 2016). All of these capacities develop best within the context of a caregiving environment that includes family, community, and cultural expectations for young children (Parlakian & Seibel, 2002). [1]

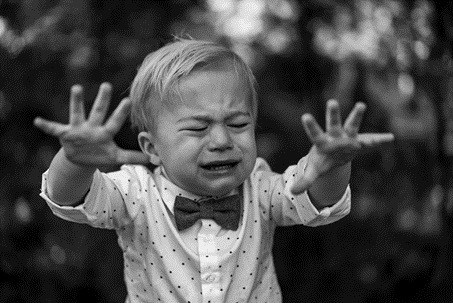

Research has established that infants and toddlers can suffer from mental health disorders that require treatment in their own right (Warner & Pottick, 2006; Zero to Three, 2012). Difficulties in infancy include regulatory disturbances such as excessive crying, sleeping or feeding difficulties and attachment difficulties (Postert et al., 2012; Zero to Three, 2016). Early childhood mental health problems include externalizing behaviors such as aggression and oppositional defiance (Egger & Angold, 2006; Loeber et al., 2009), and internalizing problems such as anxiety and depression (Bayer et al., 2011; Costello, Egger & Angold, 2005; Rapee, Schniering & Hudson, 2009). [1]

Several epidemiological studies have determined the prevalence of mental health disorders in infants and young children, indicating a 16% to 18% prevalence of mental health disorders amongst children between 1 to 5 years of age, with approximately half of these children being severely impacted (von Klitzing, Döhnert, Kroll & Grube, 2015). One study found that almost 35% of children between 12 to 18 months of age scored high on the Problem Scale of the Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA) (Horwitz et al., 2013), while another study found that by 18 months of age, 16% to 18% of children met criteria for one or more diagnoses of a mental health or developmental disorder (Skovgaard et al., 2007). Similar results were reported by an Australian study, which found that by 2 years of age, 12% of children had clinically significant emotional, behavioral, or social problems in the context of caregiver-child relationship disturbance (Bayer et al., 2011). In addition to this, a different Australian study found that by age five, 20% of the children studied had clinically significant behavioral problems (Robinson et al., 2008). It is important to recognize that most recent epidemiological studies have been conducted in developed, economically stable, peaceful countries (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2017). Evidence suggests that rates of mental health difficulties may be much higher in countries where extreme poverty, war, family displacement and trauma exist (Tomlinson et al., 2014). [1]

If not treated, mental health difficulties that begin early in life can become more serious over time (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2006; Clinton et al., 2016; Lavigne et al., 1998; Shaw, Gilliom Ingoldsby & Nagin, 2003; Slemming et al., 2010; Suveg, Southam-Gerow, Goodman & Kendall, 2007), and can persist into adolescence and adulthood (Bayer et al., 2011; Bor, McGee & Fagan, 2004; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2008). Children with mental health problems are at higher risk for later difficulties at school, difficulties with peers, difficulty participating in employment, drug and alcohol problems, relationship breakdown, family violence, criminal activity, juvenile delinquency and suicide (Bayer et al., 2008; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2008). [1]

Risk Factors for Infant and Toddler Mental Health Problems

There is international consensus that the first 1,000 days of life一the period of development from conception to age two一represent a crucial period of rapid physical, psychological and neurological growth (Darling, Bamidis, Burberry & Rudolf, 2020; Moore et al., 2017). During this time there is an increased likelihood that detrimental experiences such as early trauma or deprivation will be especially harmful and greatly impact future development, with adverse effects potentially developing into lifelong consequences (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2017; Moore et al., 2017; Shonkoff et al., 2012). [1]

Researchers have identified several risk factors for poor mental health in infants, taking into account the interaction between the individual child’s genetics, temperament and environment (McLuckie et al., 2019). Risks in the child include the presence of physical health difficulties, a difficult temperament, and insecure and disorganized attachment patterns (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006; Edwards et al., 2010; Miner & Clarke-Stewart, 2008; Van Zeijl et al., 2006; Wlodarczyk et al., 2017). Family based risk factors include parenting interactions that are insensitive, lack warmth, or are controlling, as well as caregiver interactions that are over involved or over protective. Other factors include overly harsh discipline, caregiver mental health difficulties or stress, parental substance abuse, family violence, limited parental education, and parental conflict or separation/divorce (Ashford et al., 2008; Bayer et al., 2011; Bayer, Sanson & Hemphill, 2006; Dwyer et al., 2003; Edwards et al., 2010; McCarty, Zimmerman, Digiuseppe & Christakis, 2005; Miner & Clarke-Stewart, 2008; Pike et al., 2006; Van Zeijl et al., 2006; Wlodarczyk et al., 2017). [1]

Infant & Toddler Mental Health: Protective Factors

Attachment theory asserts that the relationship between the infant and their primary caregivers has an important influence on the development of the capacity for emotional and behavioral regulation (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Bowlby, 1969). A large body of evidence has identified that an infant’s developing brain is shaped by the quality of the caregiving environment provided by their primary caregivers (Kerns & Brumariu, 2014; Lally & Mangione, 2017). Secure primary attachment relationships, although not a guarantee against future mental health difficulties, are influential protective factors for infant and young children’s mental health. A secure attachment relationship allows the infant’s developing brain to develop capacities in building and maintaining relationships, emotional regulation, attention and self-control and sets a strong foundation for the later development of resilience, confidence and adaptability (Balbernie, 2013; Benoit, 2004). Researchers have consistently found that securely attached children experience stronger relationships with their caregivers as well as enhanced problem solving abilities, improved peer relationships and longer lasting friendships (Abraham & Kerns, 2013; Guild et al., 2017; Schneider, Atkinson & Tardif, 2001). These children may also have better sibling relationships, more positive self-esteem, an increased sense of hopefulness, greater trust in people and relationships, and heightened optimism about their future compared to children with insecure attachment styles. In contrast, insecure and disorganized attachment styles in infancy have been associated with elevated rates of emotional, social and behavioral disturbances in infancy, toddlerhood, preschool and beyond (Berlin, 2008; Fearon et al., 2010; Granot & Mayseless, 2001; Madigan, Atkinson, Laurin & Benoit, 2013; Sroufe, 2005; Van Ijzendoorn, Schuengel & Bakermans–Kranenburg, 1999). A 30-year prospective study of infants with insecure attachment styles at 8 months of age, found insecure attachment to be associated with a higher risk of mental health concerns later in adulthood at 30 years of age (Fan et al., 2014). Disorganized attachment in infancy is associated with the highest risk of later social and cognitive difficulties and psychopathology with an association found between disorganized infant attachment and childhood behavior problems (Van Ijzendoorn et al., 1999), externalizing and internalizing problems in early school years, aggression and oppositional defiant disorder (Fearon et al., 2010; Green & Goldwyn, 2002), and personality disorder (Steele & Siever, 2010). Studies have found disorganized attachment is significantly correlated with psychopathology in adolescence (Carlson et al., 1998), borderline personality disorder symptoms in adulthood (Carlson et al., 2009), dissociation (Lyons-Ruth, 2003); and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Macdonald et al., 2008). [1]

Ideally, caregivers are able to tune into their baby’s cues, interpret their meaning, and respond to them in a contingent, consistent and competent way, which has been termed sensitive parenting (Ensink et al., 2016; Petch et al., 2012). Caregivers who provide care in this way allow their infant to develop optimal early social-emotional skills, secure infant-caregiver relationships and cognitive ability (The National Health and Medical Research Council, 2017).

Infant & Toddler Mental Health: Prevention & Early Intervention

Research highlights the importance of childhood experiences across the lifespan, starting in infancy and toddlerhood, emphasizing the importance of addressing risk factors early in life (Felitti et al., 1998; Jones, Nurius, Song & Fleming, 2018). The cost of mental health disorders on individuals and society demands a response that focuses on early investment, health promotion and early intervention in an effort to positively impact future health (Jenkins et al., 2002). The World Health Organization has asserted that prevention is the only sustainable approach for reducing the health burden associated with mental health disorders (World Health Organization, 2004). It is well established that early detection, assessment and intervention of mental health problems in infancy and early childhood is more successful and cost effective than treatment when symptoms become more severe (Davis et al., 2010; Huberty, 2012; The National Health and Medical Research Council, 2017). [1]

This shift in focus toward the prevention of mental illness means that we must consider the mental health and wellbeing of infants, young children, and their parents (Guy, Furber, Leach & Segal, 2016). While the period of infancy and early childhood is a time when mental health difficulties can develop, it is also an enormously influential developmental stage with the potential to modify or prevent these same difficulties (Karevold, Røysamb, Ystrom & Mathiesen, 2009; Lewis et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2017). Since many disorders can be prevented through developmentally appropriate, high quality programs and services, it is becoming increasingly acknowledged that it is not enough to merely treat mental health disorders as they emerge (Andrews & Wilkinson, 2002; Waddell et al., 2007). Instead, research suggests that efforts should focus on the prevention of mental health difficulties before they arise, particularly during the earliest stages of life when there is the greatest capacity to effect change (Bayer et al., 2010; Maldonado-Duran, Lartigue & Feintuch, 2000; The National Health and Medical Research Council, 2017). [1]

To support optimal mental health in infants and toddlers, caregivers can:

- Continue to learn and stay informed about the epidemiology (incidence and possible causes) of mental health in children under three years of age.

- Establish secure relationships with infants and toddlers, with a focus on children who show early signs of an insecure attachment.

- Engage in sensitive caregiving by tuning into a child’s unique cues, interpreting their meaning, and responding to them in a contingent, consistent and competent way.

- Create safe physical and social environments where children can practice regulating and expressing their emotions.

- Share knowledge of positive caregiving practices and awareness of infant and toddler mental health with families.

[1] Izett et al., (2021). Prevention of mental health difficulties for children aged 0–3 years: A review. Frontiers in Psychology, 2794. CC by 4.0

[2] Image by Nina Hill on Unsplash.

[3] Image by Alexander Dummer on Unsplash.

[4] Image by Zachary Kadolph on Unsplash.

[5] Image by Katie Emslie on Unsplash.