5.3: Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Page ID

- 139790

Childhood Experiences

Throughout our lives, from childhood into adulthood, we will likely encounter adverse experiences一unfavorable experiences that have the potential to hold us back from success or development. Specific types of adverse experiences that occur during childhood are especially concerning because they can decrease the likelihood that children will develop optimally (Bethell, Simpson & Solloway, 2017; Shonkoff, 2010) by threatening the development of positive social, emotional, and cognitive growth in children (Belsky, 1984; Bradley & Corwyn, 2002). Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0 to 17 years) such as experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect; witnessing violence in the home; and having a family member attempt or die by suicide (Felitti et al., 1998). [1] [2]

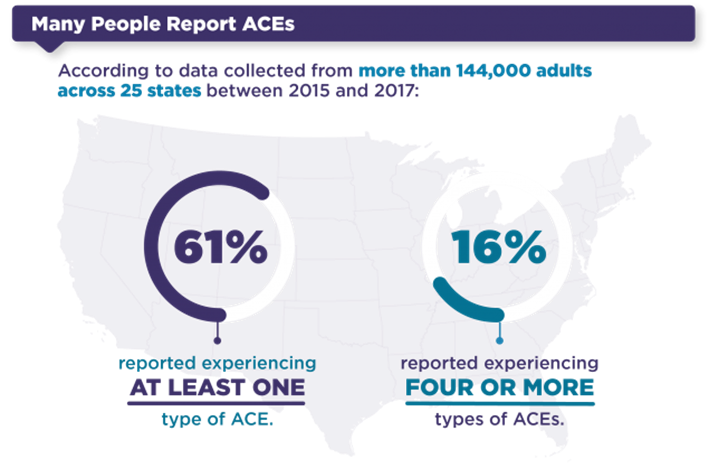

The ACE index (Anda et al. 2006; CDC, 2022; Felitti 1993) includes the ten indicators listed in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). Half of the indicators assess child maltreatment, including physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and physical and emotional neglect. The remaining five indicators are characteristics of the caregiver or home environment. These include living with a family member with a mental illness, a substance use problem, a history of incarceration, living in a home with domestic violence, or living in a home with parents who have separated or divorced. The Centers for Disease Control reported 61% of adults across twenty-five U.S. states have experienced exposure to one or more ACEs and 16% have experienced four or more ACEs. National Survey of Children’s Health data suggests 33.3% of children aged birth to 17 in the U.S. have experienced at least one family adversity (Health Resources and Services Administration 2019). [1] [2]

The ACEs study documented a set of specific events in childhood that were linked to chronic diseases and even early mortality later in adulthood (Anda et al. 2006; Felitti et al. 1998; Oh et al., 2018). The ACEs study found relationships between developmental outcomes and the number of early ACEs. As the number of ACEs increased, the likelihood of less optimal outcomes also increased. Anda et al. (2006) reported that individuals with the highest number of ACEs experienced nearly three times the number of comorbid outcomes compared with those with no ACEs exposure. A growing body of research has since further confirmed that childhood adversity is associated with chronic disease and early death (Brown et al., 2009; Campbell, Walker & Egede, 2016; Gilbert et al., 2015; Kalmakis & Chandler, 2015). [1] [7]

The Center for Youth Wellness analyzed ACEs data specific to California (Center for Youth Wellness, 2014). In California, 61.7% of adults have experienced at least one ACE and 16.7% have experienced four or more, very similar to the national averages reported by the CDC. The three most common types of ACES were emotional abuse or verbal abuse (34.9%), parental separation or divorce (26.7%) and substance abuse by a household member (26.1%). The prevalence of ACEs differed by county. Butte county had the highest prevalence of four or more ACEs at 30.3%, while San Francisco had the lowest prevalence of four or more ACEs at only 9%. Importantly, ACEs were associated with health outcomes. Individuals with four or more ACEs were five times more likely to suffer from depression and were more likely to smoke and binge drink.

ACEs are a global concern with high rates of prevalence worldwide. Approximately 61% of women living in Mexico reported at least one ACE and 14% reported four or more (Flores-Torres et al., 2020). In Malawi, 72% of adolescents (aged 10 to 16 years) reported four or more ACEs (Kidman, Piccolo & Kohler, 2020). About 63.9 % of adults in Singapore have experienced at least one ACE (Subramaniam et al., 2020). In Canada, 61.6% reported at least one ACE and 35.6% reported at least two ACEs (Joshi et al., 2021).

Awareness of ACEs and their potential negative impact on the health and wellness of individuals is increasing. For example, in 2019, California appointed its first ever Surgeon General, Nadine Burke Harris. Dr. Burke Harris is a pediatrician and her research and interests include ACEs as a top concern (Harris, 2018). Nadine helped establish the ACEs Aware Initiative and corresponding website which offers free information, training and ACEs screening tools.

Most ACEs research is conducted by asking adults to reflect upon their childhood. This approach is limited because many adults are not able to remember most events that occur before the age of three (Hayne, 2004). As the first three years are so critical for establishing a strong foundation of health and development, it is important to know how prevalent ACEs are in the lives of infants and toddlers.

Evidence suggests that many children are at risk of experiencing ACEs during the first three years. While most children under three years of age have not experienced any ACEs, 20% had experienced one ACE and 8% had experienced two or more ACEs (Novoa & Morrissey, 2020). Toddlers were twice as likely to experience at least one ACE (11%), compared to infants (5%). Infants and toddlers of color disproportionately experience ACEs, especially multiple ACEs. For example, compared to only 7% of white children, 15% of Black children under three years of age had experienced multiple ACEs. There were differences in the level of ACEs in infants and toddlers across states in the U.S. Oregon and Oklahoma had the highest percentage of children who had only experienced one ACE, both at 26%, compared to Maryland that had the lowest percentage at 15%. For children experiencing two or more ACEs, the highest percentage was in Oklahoma at 21%, while Maryland and Massachusetts had the lowest percentage, both at 3%. In California, 23% of infants and toddlers had experienced one ACE and 5% had experienced two or more ACEs.

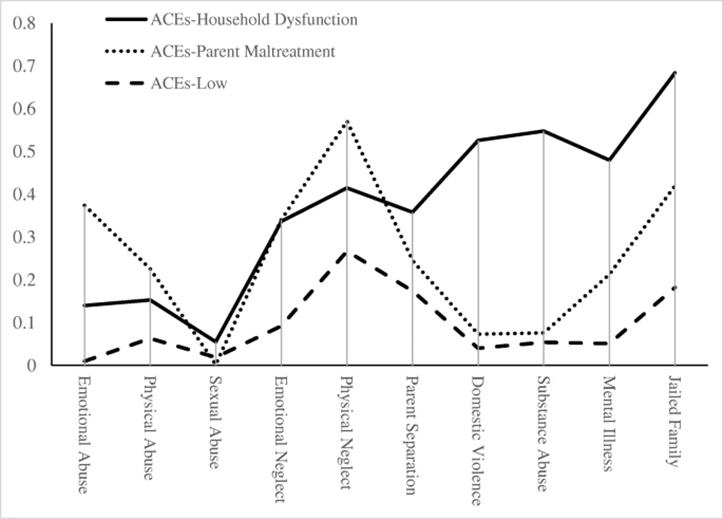

One study examined ACEs in 2,361 fourteen month old toddlers by asking parents to complete an ACEs questionnaire (McKelvey, Whiteside-Mansell, Zhang & Selig, 2020). Their data identified three different patterns. One pattern was for infants exposed to relatively low incidences of ACEs (they called this group ‘low-ACEs’). Two groups of higher ACE exposures were also identified: an ‘ACEs-parent maltreatment’ group who experienced moderate level of overall ACEs, mainly related to forms of maltreatment and an ‘ACEs-household dysfunction’ group with the highest overall ACE scores who mainly experienced multiple forms of family and household dysfunction. [1]

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows the prevalence of each of the three groups for each of the ten ACEs indicators. The low-ACEs group shows relatively low levels of ACE exposure with some elevation on physical neglect (27%) and parent separation (17%). For example, only 1% of this group exhibited emotional abuse compared with 37% and 14% in the other groups. The ACEs-parent maltreatment group has the highest levels of exposure to emotional abuse (37%), physical abuse (23%), and physical neglect (57%) compared with rates of 1%, 6%, and 27% respectively in the low-ACEs group and 14%, 15% and 42% respectively in the ACEs-household dysfunction group. The ACEs-household dysfunction group has the highest levels of exposure for parent separation (36%), domestic violence (53%), substance abuse (55%), mental illness (48%), and jailed family members (68%). [1]

The groups were significantly different in level of maternal education with the lowest educated mothers being more likely to be in the ACEs-parent maltreatment group and higher educated mothers being more likely in the ACEs-household dysfunction group. The groups also differed by race, such that Black mothers were more likely to be in the ACEs-parent maltreatment group, and Hispanic mothers were more likely to be in the low-ACEs group relative to other groups. For maternal age, the low-ACEs group had the oldest mothers and the ACEs-parent maltreatment group were the youngest. [1]

While the findings of ACEs prevalence are robust, there are potential weaknesses in the tools used to collect the data. One concern is that each of the ACE risks is weighted equally. This is a concern because some risks are more likely to predict difficult outcomes than others. For example, ACEs include sexual abuse and parental divorce/separation. Both are associated with less optimal outcomes, but research suggests that sexual abuse is a more robust predictor of negative developmental outcomes. Furthermore, the stress response to an ACE may differ amongst individuals–we do not all respond in the same way to adverse events. Therefore, to truly understand the potential negative impact ACEs can have, we must understand the relationship between adversity and stress. [1]

[1] McKelvey et al., (2020). Adverse childhood experiences in infancy: a latent class approach exploring interrelatedness of risks. Adversity and Resilience Science, 1-13. CC by 4.0

[2] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Preventing adverse childhood experiences: Leveraging the best available evidence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public domain.

[3] Image from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Preventing adverse childhood experiences: Leveraging the best available evidence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public domain.

[4] McKelvey et al., (2020). Adverse childhood experiences in infancy: a latent class approach exploring interrelatedness of risks. Adversity and Resilience Science, 1-13. CC by 4.0

[5] “Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences” from the CDC is in the public domain.

[6] Image from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Preventing adverse childhood experiences: Leveraging the best available evidence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public domain.

[7] Oh et al., (2018). Systematic review of pediatric health outcomes associated with childhood adversity. BMC Pediatrics, 18(1), 1-19. CC by 4.0

[8] Image by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash.

[9] Image by Christopher Michel on Wikipedia is licensed under CC by 2.0

[10] Figure 1 from McKelvey et al., (2020). Adverse childhood experiences in infancy: a latent class approach exploring interrelatedness of risks. Adversity and Resilience Science, 1-13. CC by 4.0