13.2: Language Growth and Individual Differences

- Page ID

- 140675

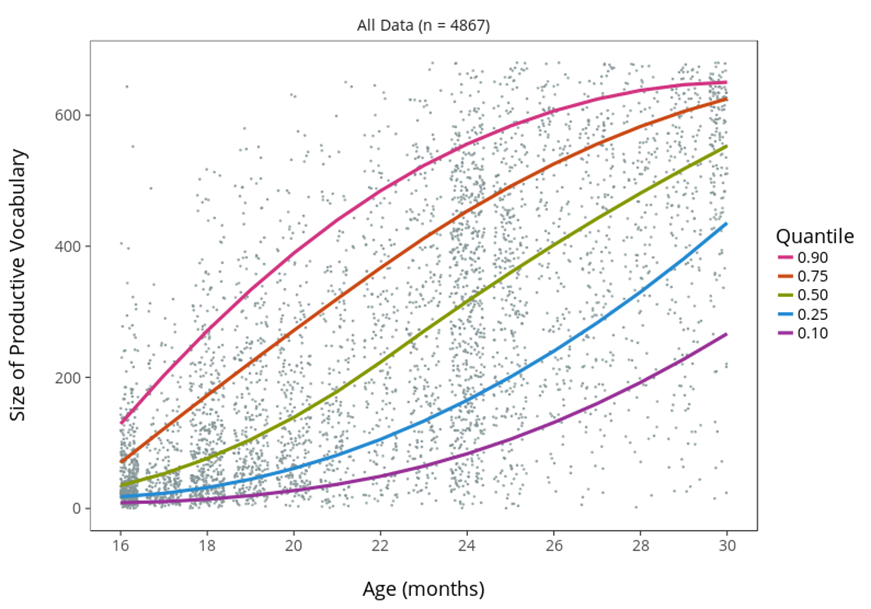

Individuality of Language Growth

Language develops rapidly during the first three years of life. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows growth curves for the development of toddlers’ productive vocabulary between 16 to 30 months of age. On the x-axis is the age of children and the y-axis represents how many words children produce. Each gray dot is a child’s data. When you look at this chart closely, what do you notice? Did you notice the individual differences within each age? For example, look at the spread of dots at 24 months. Even within the same age, 24 months, there is a large variability in productive vocabulary between children. At 24 months, some children have been heard to speak more than 500 or even 600 words, while many others spoke less than 200 words. Also, notice that the growth curves suggest that these individual differences start early, before 16 months and continue throughout the second year of life. Where do these individual differences in language ability come from and do they have any long term significance?

Early individual differences in language ability does have long term significance. For example, individual differences in language processing abilities remain stable across development一those children who were faster at processing language at 19 months continued to be faster at processing language 12 months later (Peter et al., 2019). For children born prematurely, children who were faster at processing language at 18 months, had larger vocabulary comprehension abilities at 30 months (Marchman et al., 2016) and had higher scores on language and IQ at 54 months (Marchman et al., 2018). By 18 months, children from higher SES backgrounds already have larger productive vocabularies and are more efficient at processing language (Fernald, Marchman & Weisleder, 2013). When these same children were followed up six months later, those with larger vocabularies and more efficient language processing skills at 18 months continued to perform at a higher level: at two years of age, children from lower SES backgrounds performed at the level children from higher SES backgrounds did when they were 18 months old一representing a six month performance gap by age two. [2]

In summary, individual differences in language ability begin to form early in life and have the potential to lead to very different developmental outcomes later in childhood. Specifically, larger vocabularies and more efficient language processing skills in toddlerhood is related to higher performance on language, cognitive and academic assessments in later childhood. Clearly early individual differences in language ability are important, but where do they come from?

The Word Gap

The individual differences in language abilities that appear early in the first three years can be partly explained by the various levels of language exposure children recieve. For example, early language processing abilities are associated with the amount of language children hear as research has found that children who are exposed to less language tend to have lower language abilities (Fernald & Weisleder, 2010; Hurtado, Marchman & Fernald, 2008). [3]

In one important study on individual differences, researchers went into families’ homes once per month and recorded what children heard and said for one hour (Hart & Risley, 1995). They started doing this when the infants were nine months old, and they kept going to their homes every month until the children were three years old. During this time, the toddlers began to talk, and the scientists tracked every new word that they produced. They also wrote down all the words and sentences that parents said to their children. After analyzing these recordings, they found that most children started speaking around their first birthday, but some learned new words much more quickly than others did. They also found that children were better at learning new words if their parents talked to them a lot at home. Children who heard lots of language—more words, more different words, more questions, more encouraging words, and more words that described things—had bigger vocabularies than children who did not hear as much language. [5]

One important finding from this study was that children heard more language if they were from families with a higher socioeconomic status (SES). This relationship between family (SES) and the amount of words spoken to the child has become known as the word gap. Hart and Risley (2003) estimated that there is a 30 million word gap一children from higher SES families are exposed to 30 million more words by age three than children from families with a lower SES. While some researchers argue that the actual word gap may be less than the 30 million words originally proposed, the word gap is nonetheless present and impactful, as numerous studies have documented a difference in language exposure based on family SES (Ellwood‐Lowe, Foushee & Srinivasan, 2022; Hoff, 2003; Huttenlocher et al., 2010; Golinkoff et al., 2019; Rowe, Leech & Cabrera, 2017). For example, the language of parents with a lower SES often use a lower diversity of words in comparison to the language of parents with a higher SES (Burchinal et al., 2008; Huttenlocher et al., 2010). As a consequence of these input differences, children with a higher SES background often have a larger vocabulary (Gilkerson et al., 2017; Hoff, 2006) and more often use diverse and advanced grammatical constructions than children from lower SES families (Huttenlocher, Vasilyeva, Cymerman & Levine, 2002). [6]

The idea of a word gap highlights the importance of early language exposure for positive long term developmental trajectories. Early language experiences and abilities lead to stronger later language performance and are even related to later cognitive and academic abilities (Bornstein, Hahn, Putnick & Pearson, 2018; Lehrl et al., 2020; Rodriguez & Tamis‐LeMonda, 2011; Rose, Lehrl, Ebert & Weinert, 2018; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2019). For example toddlers with larger vocabularies and more efficient language processing demonstrated stronger language and cognitive skills at 8 years of age (Marchman & Fernald, 2008).

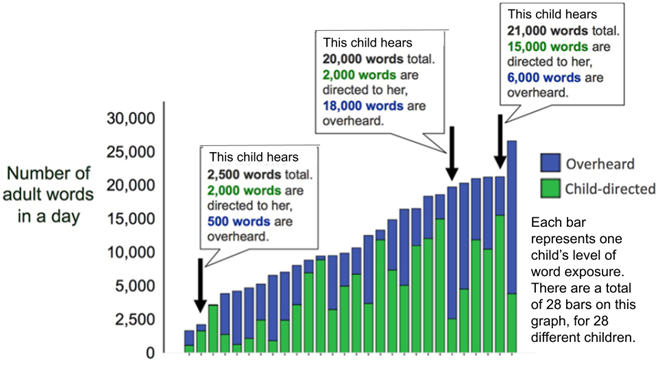

Quantity of Language Exposure

While indeed family SES is related to early language differences in children, family SES alone does not reveal the full story. In one study, researchers looked at the potential factors in language growth across a group of toddlers, all from families with a low SES (Weisleder & Fernald, 2013). Children wore a special recorder that captured the language they were exposed to throughout the day, over multiple days. Results revealed great variability in language exposure, even though the children were all from families with lower SES. Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) charts the varied language exposure of the children. Each colored column represents one child and the height of the column represents the number of words a child heard in a 10 hour day一the taller the bar, the more words heard by a child. Some children heard over 25,000 words in one day, while others heard under 2,500 words in one day. This is data from just one day, but imagine the compounding effect this has over the first three years of a child’s life if these daily patterns are repeated! [5]

These results move the spotlight away from SES per se and instead shine it more specifically on the variable language experiences of children, one of which can include SES. In general, children from families with high SES hear more language than children from families with low SES, but even within the same SES level there are significant differences in language experience. There are also other reasons besides SES for wide-ranging levels of language exposure. For example, in Senegal, cultural traditions and beliefs discourage caregivers from talking with infants and toddlers, therefore greatly restricting their language exposure (Weber, Fernald & Diop, 2017). Other research shows that the quantity of words infants experience varies greatly based on how infants are placed during activities and the type of activity. Infants placed in sitting devices (e.g., bouncy seats, highchairs) experience fewer adult words and less consistent language exposure throughout the day (Malachowski, Salo, Needham & Humphreys, 2021). Considering various daily activities, infants were exposed to the most words during book sharing (mean of 55.91 words per minute) and grooming (mean of 56.60 words per minute) and the least amount of words during object play (mean of 34.10 words per minute) and feeding (mean of 32.44 words per minute) (Tamis‐LeMonda et al., 2019).

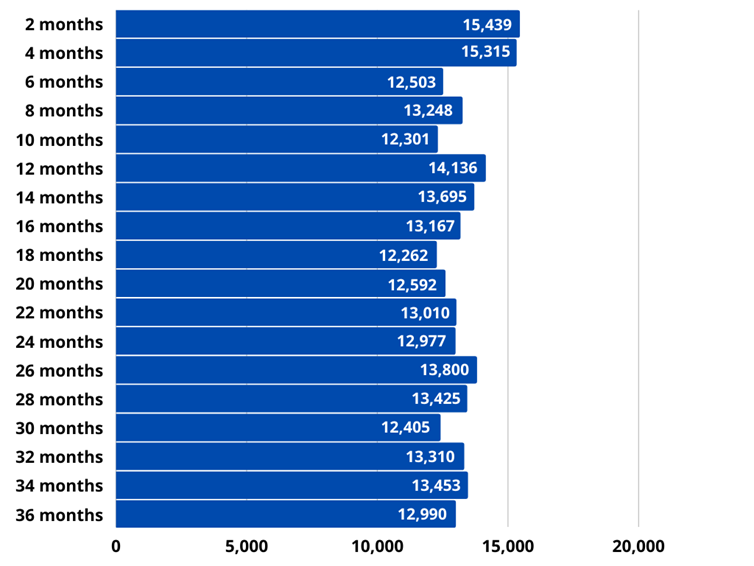

Until now we have learned that the number of words children are exposed to can vary greatly depending on factors such as SES and culture, but what does the “typical” amount of language exposure look like? To estimate how many words infants and toddlers hear across different ages, another team of researchers also used small language recorders worn by children to count the number of words infants and toddlers heard throughout the day (Gilkerson et al., 2017). Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) summarizes some of their data. Take a moment to look carefully at the data in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). What did you notice? Consider how developmental growth in other domains, such as motor abilities, might influence the amount of words children hear.

Did you notice that infants typically heard more words than toddlers, with the youngest infants, 2 to 4 months of age, hearing the most words? Why do you think infants and younger toddlers are exposed to more words than older toddlers? Across 2 to 36 months of age, children are approximately exposed to an average amount of words between the range of 12,000 to just over 15,000. Although the difference between 12,000 and 15,000 may not seem very significant, consider how these numbers could play out over just one year. A child who is exposed to 12,000 words everyday for one year would hear 4,380,000 words, but a child exposed to 15,000 words daily would hear 5,475,000 words in one year. This represents a difference of over one million words!

It is critical to stress that while this data was recorded in the child’s home environment as families moved throughout their daily routines in an attempt to capture “natural” language exposure, the data in no way should be interpreted as representing what may be “typical” language exposure for all children. The participants in the study were all monolingual English speaking children, mostly (66%) white, all from the Denver, Colorado area and educated with a high school GED (26%), some college experience (29%) and a college degree (23%). Irrespective of these limitations, the data does provide intriguing insight into daily natural language exposure for infants and toddlers.

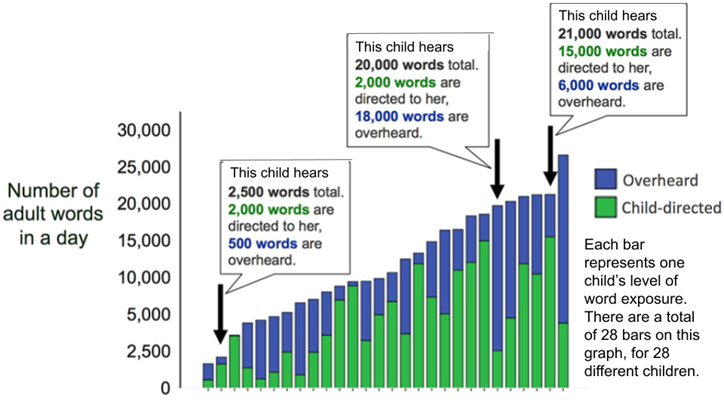

Quality of Language Exposure

While quantity, the sheer amount of language children are exposed to, is clearly important, research suggests the quality of the exposure is even more important (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015; Romeo et al., 2018). Let’s revisit the chart that showed the number of words toddlers, from low SES families, heard in one day (see Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). While the height of the columns represents the quantity of language exposure, the colored sections of the columns represent the quality of exposure. Some children heard lots of language spoken directly to them, like when they were talking and playing with their caregivers, this is referred to as child-directed speech. The bottom color of each column is green, representing the amount of words heard that were child-directed. Other children heard lots of language that was not directed to them, like when their caregivers were talking to each other or to other children nearby, this is referred to as overheard speech. The top color of each column is blue, representing the amount of overheard words. [8]

Distinguishing between the quantity of language children are exposed to is critical. The research revealed that the toddlers who heard more child-directed language had bigger vocabularies and had more efficient language processing abilities than the children who did not hear as much child-directed speech. This shows that the quality of the words caregivers use with infants and toddlers, such as child-directed speech, may be even more important than the overall quantity of language exposure.

Child-directed language is just one way to think about the quality of language infants and toddlers experience. Another way to perceive language quality is through the conversational turn counts between children and adults. Turn counts are an important quality measure because they capture the critical interactive and responsive aspect of a back-and-forth conversation. After controlling for SES, toddlers who experienced more conversational turn counts with caregivers had higher IQ scores and language abilities later in childhood at ages 9 and 13 (Gilkerson et al., 2018).

There are important early differences in the quantity and quality of language that infants and toddlers experience above and beyond SES. Research has found that both quantity and quality of language exposure during the first three years of life is related to language and cognitive abilities in later childhood. While caregivers should consider increasing the quantity of language their infants and toddlers experience, focusing on various quality aspects of their language interactions is the most important. The next session will introduce various strategies that caregivers can use to improve the quantity and quality of the language they share with infants and toddlers.

[1] Image by Wordbank is licensed under CC by 4.0

[2] Peter et al., (2019). Does speed of processing or vocabulary size predict later language growth in toddlers? Cognitive Psychology, 115, 101238. CC by 4.0

[3] Dickinson et al., (2012). How reading books fosters language development around the world. Child Development Research. CC by 3.0

[4] Image by Luiza Braun on Unsplash.

[5] Lew-Williams & Weisleder (2017). How do little kids learn language? Frontiers in Young Minds, 5(45). CC by 4.0

[6] Grolig (2020). Shared storybook reading and oral language development: A bioecological perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1818. CC by 4.0

[7] Image adapted from Lew-Williams & Weisleder (2017). How do little kids learn language? Frontiers for Young Minds, 5, 45. CC by 4.0

[8] Image by Todd LaMarr is licensed under CC by 4.0.

[9] Image by Luiza Braun on Unsplash.